Paul Klee, life, works and style of the abstract painter

Paul Kle e (Ernst Paul Klee; Münchenbuchsee, 1879 - Muralto, 1940) was one of the leading exponents of the current ofabstractionism in the early twentieth century. A multifaceted artist, he successfully tried his hand at various disciplines until he found his true expression in painting. Klee grew up in an environment where music was omnipresent: not surprisingly, he considered his paintings to be like a musical composition.

During his lifetime, Klee came into contact with several great masters, whom he met in person or through their masterpieces, reinterpreting and reasoning about their works and painting in a completely personal way. He was also part of the famous Der Blaue Reiter (“the blue knight”) group, which was part of the broader current ofGerman Expressionism. We are aware of several details of his life thanks to a series of autobiographical writings, titled “Diaries,” which accompany us throughout Paul Klee’s existence, from his various moves between Switzerland and Germany, to his military service during World War I, to his illness, without ever stopping painting.

Life of Paul Klee

Ernst Paul Klee was born on December 18, 1879, in Münchenbuchsee, a small town in Switzerland near Bern. His father, Hans Klee, was a German music professor while his mother, Ida Frick, was a Swiss opera singer. From childhood, therefore, Klee came into direct contact with music and was encouraged by his father to study its basics. He carried this training with him throughout his subsequent artistic pursuit in painting. Klee came into contact with drawing as a child through his maternal grandmother, while in the meantime he began his first violin lessons and wrote poetic verse daily, demonstrating multiple skills and passions from an early age and continuing to cultivate them all throughout his youth. Later he joined theBern Symphony Orchestra specifically as a violinist.

In 1899 the Klee family moved to Munich, in the artists’ district. Klee continued to try his hand at all the arts without preferring any one in particular, until he decided to enroll in the Academy of Fine Arts. However, he then had to attend a private drawing school, as he was not admitted to the Academy because of deficiencies in the subject of Figure Drawing. During this period, Klee began a new personal artistic pursuit, focusing more on line than color, leading to his first experiments with etchings. In 1900 he was able to enroll at the Academy, where he attended classes together with a Russian student who was destined like him to become a big name in abstractionism: Vasily Kandinsky. In the course of his studies he also came into contact with the Jugendstil current, a German version ofArt Nouveau. In addition, one of Klee’s professors was Franz von Stuck, founder of the first Munich Secession. Von Stuck’s figure was very influential on Klee, so much so that he accepted his professor’s advice to visit Italy. Klee stayed in our country a few months, visiting several cities and being fascinated by the artistic masterpieces and landscapes, reluctantly leaving it to return to Bern. Once back, Klee continued his studies as a self-taught artist while simultaneously taking an evening course in nudity and plastic anatomy.

Between 1903 and 1905 the artist produced a series of etchings entitled Inventions, in which real and fantasy images (beings with grotesque and deformed features appear) are mixed together. During these years Klee also had the opportunity to visit Paris, where he met the Impressionists, and to study several engravers, including Francisco Goya and his Capriccios, which turn out to be very close to his Inventions. In 1906 he exhibited the Inventions in the Secession exhibition in Munich, and the uniqueness of the collection intrigued several critics. That same year, Klee married a pianist he had met several years earlier, Caroline “Lily” Stumpf, and the two had their only child, Felix, the following year. Klee was a very caring and present father in his son’s life; indeed, he often took much of his time and energy away from art to devote himself to the little boy’s ailing health. In the Diaries, we read that Klee identifies this as the period of his stylistic maturity. During these years he made very small, miniature paintings, the format of which was most likely due more to the size of the very small apartment he had moved into with his family in Munich than to any particular stylistic choices.

In 1908 he participated in a Munich Secession exhibition with a number of paintings in which it is possible to see some inspiration from Vincent van Gogh, whose exhibition he had seen. Another artist who influenced Klee’s works in the immediately following years was Paul Cézanne, in fact the paintings made between 1908 and 1911 depict landscapes en plein air. Moreover, Klee wrote explicitly that he considered Cézanne his master. In 1911, Klee’s circle of acquaintances led him first to create the Sema group together with Schiele and Kubin, with the intention of finding the essential reduction of elements. Later, he joined August Macke, Franz Marc and Vasily Kandinsky in the famous group Der Blaue Reiter, initially known as Neue Künstlervereinigung (“New Union of Artists”), which aimed to create a support network for young painters in Munich. Klee exhibited together with the other members of Der Blaue Reiter in the second exhibition organized by the collective. He also joined the New Munich Secession in 1913.

In 1914 there was an episode that proved fundamental to Klee’s artistic development, and in particular to his relationship with color: in that year he undertook a two-week trip to Tunis and Hammamet together with Macke and Louis Moilliet. From that time, in fact, Klee began to use warm, luminous hues in his paintings, typical of the landscapes of Tunisia. He wrote in the Diaries that this was the happiest time of his life, as he felt he had no worries and called himself to all intents and purposes a painter, in deep contact with color. In 1916, already at the age of thirty-six, he was called to serve in World War I for two years, narrowly saved from the front due to the deaths in the field of other artists, so the King of Bavaria decided not to send any more Munich painters into battle. In spite of the commitments he still had to endure during his service, he continued to paint quite prolifically. At the end of his military service, he returned to Switzerland and in 1920 was called by Walter Gropius to the Bauhaus in Weimar as a professor of painting. There he also found his friend Kandinsky again. Klee in his lectures gave equal importance to scientific training and the poetic side of painting, finding a great following among his students. However, Klee always remained somewhat aloof as a teacher, in a way emphasizing the idea of not dealing with actual artists. Gropius called him “the extreme moral instance of the Bauhaus.”

In 1924 the Bauhaus, and consequently Klee as well, was transferred to Dessau because of hostilities that had arisen in Weimar. Klee continued to teach but gradually began to take more and more time off to make trips to Switzerland and France and to paint, meeting with remonstrances from Bauhaus management for his lack of constancy. The teaching commitment for Klee became too pressing, so he left the Bauhaus and sought other institutions where he could teach at a slower pace, landing at the Dusseldorf Academy in 1931. The experience, however, lasted a couple of years until he was forced to be dismissed by the Nazi regime, and he had to return to his hometown, where he continued to paint works with sad and somber tones clearly influenced by the horrors of World War II. Nevertheless, Klee’s popularity in these years was well established and consecrated by a series of successful exhibitions throughout Europe, from London to France, and even outside, reaching as far as the United States. The Nazi regime was not of the same opinion with respect to the consensus Klee was gaining and placed his works on the list of “degenerate” artists to be censored (read an in-depth discussion of degenerate art here), removing all his works from German museums. The affection of many artists who, in solidarity with what was happening, visited him in Switzerland, gave him the impetus he needed to continue to execute experimental works. He never stopped painting during these years, despite the fact that he began to experience the first symptoms of a progressive scleroderma that was debilitating him more and more. As his health deteriorated, he was transferred to some clinics near Locarno. He later died in Muralto, near Locarno, on June 29, 1940, a few months after losing his father.

Klee’s style

Paul Klee was a very prolific artist who explored a variety of painting techniques and materials: he made drawings, etchings, etchings, oil, watercolor, and pastel paintings on numerous media ranging from canvas to wood, cardboard to linen. He built or reworked various tools, such as color sprayers or the compass used without a lead to mark circular shapes on canvas, in order to achieve the desired result. Fundamental to Klee was giving form to the unseen. “Art,” the painter asserted, “does not represent the visible, but makes visible what is not visible.” Compared to Kandinsky’s abstraction, however, Klee’s is moved by different foundations: indeed, Klee’s works hardly abandon figuration altogether. His idea is, if anything, to understand the origins of forms.

Klee’s works are part of the current ofabstractionism, a mode of representation in which reality is not reproduced in a traditional way, but its reasoning is returned, which the different artists investigate in a personal way, trying to identify its deeper mechanisms.On abstract canvases, in fact, we find shapes and colors that constitute the equivalent of natural elements, even when these are completely different from the real ones. Paul Klee would gradually arrive at abstractionism in the course of his artistic life, but from the earliest works it is possible to notice the presence of non-real elements, although still rendered through canonical forms of drawing. Indeed, the early production focuses on fully figurative etchings that demonstrate a remarkable capacity for imagination and fantasy combined with a high level of technique. This is exemplified in the collection Inventions, where we find as the main subject fantastic figures that combine reality and imagination by exacerbating certain details, even touching on the grotesque and caricatural. Beneath the depiction of these elements, Klee actually conceals a veiled criticism of the bourgeoisie. See for example Komiker (1904),

For a period, between 1908 and 1911, nature is present in a series of landscape drawings explicitly inspired by Cézanne, from which, however, he differs by a symbolic analysis of forms and not rendered through objective reproduction. Joining the Der Blaue Reiter group is the impetus that leads Klee to reason around light and color, of which he has not yet found full resolution, however. He will find it three years later far from home, during the 1914 trip to Tunisia. This is the real turning point in Klee’s painting, as he finally embraces color in its totality, feeling himself a painter in his own right. Forms, in the works of this period, are present but in a very symbolic and evocative way. See, for example, Red and White Domes of 1914, in which Klee brings back visual suggestions derived from contact with the Tunisian architectural landscape, consisting of dense clusters of houses, through a grid of brightly juxtaposed blocks of color. This device will return very often in the Swiss artist’s later works.

This balance between color and symbolism continues to be present in works created during World War I, such as In Front of the Gas Lamp (1915), in which experiments in this regard reach their climax. The painting, moreover, presents a precise stylistic feature of Klee’s: a “picture within a picture” as if it were a second frame, made by drawing a rectangle in which the main scene is inserted.

His years as a teacher at the Bauhaus led him to confront rationalism, from which he drew without, however, becoming fully involved, continuing his own research into color. See, for example, Separation in the Evening (1922) where the elements are rationally placed in space and yet do not appear to be motionless, but rather seem to move in space by increasing and decreasing. From here, we can even more explicitly identify the artist’s very deep relationship with music. In the work in question and in numerous other paintings, in fact, Klee reproduces patterns typical of a musical composition, such as scales of notes or the propagation of vibrations. See, for example, Escape in Red (1921), which already in its title reveals a connection to this world and even more explicitly makes it explicit through the presence of figures that vibrate as if emanating sound.

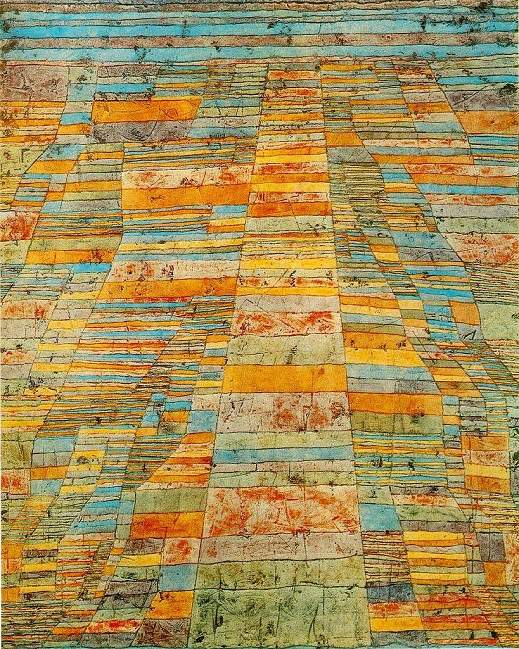

Towards the end of the 1920s, Klee produced two works, among his most famous, in which he seems to have achieved a balance between all the elements that had characterized his paintings up to that time: the sun (both through the circular form and through luminosity), the blocks arranged in a grid, the color juxtapositions, the musical rhythm, and the Tunisian architectural landscapes, find fulfillment and sublimation in Castle and Sun of 1928 and Main and Secondary Streets of 1929. The last period of Klee’s life and art, as noted earlier, is conditioned by a series of negative events, between the advent of Nazism and the first signs of illness. Not surprisingly, in the works of this period we see large black and dark marks with ominous tones appearing, raging over dense, mellow colors. Look at Revolution of the Viaduct and Look from the Red both made in 1937. Klee painted until the last day of his life. In fact, it is said that when he died, there was a painting still in progress on his easel.

Where to see Klee’s works

The Zentrum Paul Klee, a museum dedicated to learning about the artist’s work, has been established in Bern, Switzerland. It is home to a research institute dedicated to the painter in addition to 40 percent of Klee’s total works. Within the Zentrum’s permanent collection are also works by other artists, who gave them to Klee and thus he kept them among his private possessions, including paintings by Kandinsky and Marc. The museum was opened in 2005 in a building constructed based on a design by Renzo Piano.

Another important nucleus of works is kept at the Kunstmuseum, also in Bern, and within private collections. Other works can be found in Germany, in Basel (Kunstmuseum) Dusseldorf and Munich, in Madrid, and in Rome (National Gallery of Modern Art). Outside Europe, some of Klee’s paintings can be seen in major museums in New York (Metropolitan Museum of Modern Art and Museum of Modern Art). In Italy, apart from the two paintings at the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice ( Portrait of Frau P. in the South and Magic Garden), there are no works by Klee, but several exhibitions have been organized, including “Klee and Italy” set up in 2013 at the National Gallery of Modern Art in Rome and “Klee and Primitivism” at the Museum of Cultures in Milan between 2018 and 2019(read the review here).

|

| Paul Klee, life, works and style of the abstract painter |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.