Piero di Cosimo (Pietro di Lorenzo; Florence, 1462 - 1522) was a very curious Florentine painter, a genius endowed with great imagination. For this reason he ranks among that group of the most original artists of the early sixteenth century who would later lead to the twists typical of the Mannerist style. He began his apprenticeship in the Florence of the 1570s and, while always working alongside the most famous masters of the day, distinguished himself through the eccentric creative spirit for which he is still known and appreciated today.

As easily as Piero measured himself against the artists of his time, he never cared to fit into the artistic milieu of Florence. Indeed, it was not until January 1504 that his name first appeared in a public document: he and twenty-eight other artists (including Leonardo, Botticelli, and Filippino Lippi) were being asked for their opinion about the placement of Michelangelo’s David. A few months later he asked for registration in the art of the Medici and Speziali. At the time, Piero di Cosimo was over forty years old and had been working in Florence for at least twenty-five. Although his unquestioned skills procured him important patrons from among the city’s most illustrious families, all this time he remained on the margins of the Florentine scene.

He was a nonconformist: critics have always considered him a whimsical painter, a difficult person. It is Giorgio Vasari who opens up this trend and, while attributing to him an “abstract and dissimilar wit,” recounts his life as if it were a novel, willingly yielding to anecdote. The little information we know about Piero’s life we owe to him, who gives us a portrait of the artist as a man who lived apart, according to his own rules, detached from society, but a very attentive admirer of nature (an aspect, the latter, that often brought him close to the genius of Leonardo). And it was precisely according to nature that he wanted to live, letting it take its course: a barren, animalistic attitude gave him that wild aura that can be discerned in his works.

Because of this character of his (although it was more likely a choice, a conscious life thought) his art is made up of whimsical inventions, of imaginative eloquence. He also created works with religious content, but it was mainly in the secular and mythological production that his grotesque, complex and vibrant figurative language found free field. It was precisely because of this uncommon fervor that animated him that he would continue to be taken up and reread over the centuries: he knew an important critical fortune in the nineteenth century, amid recoveries, new attributions and exhibitions. From the beginning of the 20th century many works were wrongly attributed to him, because by then there was a tendency to think that wherever there was something grotesque, then there was his hand. Piero’s art was revived with André Breton, who, fascinated, juxtaposed it with that of Leonardo and Paolo Uccello, and evoked the painter in his theories on surrealism, restoring his conception of art at its most magical.

Piero di Lorenzo was born between 1461 and 1462 in Florence to a family of artisans. Piero’s father Lorenzo, according to Vasari, was a goldsmith by trade, but all documents lead him back to the trade of “succhiellinaio,” that is, a craftsman of modest origins. Business had to get in a good direction, because in 1469 Lorenzo di Piero claimed to own two houses, and assets increased with the addition of land in the countryside. The artist was called “di Cosimo” because at the age of eighteen he was placed in the workshop of Cosimo Rosselli, after a somewhat restless adolescence. In 1481, Pope Sixtus IV called a team of Florentine painters to the Vatican to paint frescoes in the Sistine Chapel before Michelangelo’s intervention. Lorenzo the Magnificent sent the best, among whom was Cosimo Rosselli. And the latter was so fond of the boy that he took him with him: “he bore him love as to a son and as such he always kept him” (Vasari); Rosselli evidently felt no jealousy of trade for the boy, for, according to Vasari, he “often often had him conduct many works that were of importance, knowing that Piero had and finer manner and better judgment than he.” Thus, not only did he distinguish himself for bravura and originality on the scaffolding of the Sistine Chapel, but, at the same time, the young painter was free to take in and rework the stimuli offered by that environment, finding comparison and learning from the other masters. In this way he formed his own style without the interference of the master.

The intervention in the Sistine Chapel is a secure date in Piero’s life, along with that of his death, 1522 (to be disproved by Vasari, according to whom the artist disappeared in 1521). Piero’s biography is composed of these few facts. The real narrative, the one that contributed to the painter’s fortune, is built around his temperament, which the Aretine historiographer illustrates through various anecdotes: the “strangeness of his brain,” he writes, was sharpened by the death of his master Cosimo. “He was locked up and would not let himself be seen working,” Vasari writes, “and he kept a life of a huomo more bestial than humano. He did not want the rooms to be swept, he wanted to eat then that hunger came, and he did not want the fruits of the horto to be hoed or pruned, rather he let the vines grow and the shoots go on the ground, and the figs were never pruned nor the other trees, rather he was content to see everything saved, as was his nature; ... the things of it nature must be left to her to guard without doing anything else to you. He went often to see either animals or herbs or some thing that nature does by istranezza and accaso of many times, and he had a contentment and a satisfaction of it that furad him all to himself.”

Misanthropic, inselvatichito like his deliberately neglected vegetable garden: Piero certainly had a quirky and extravagant character, but his attitude to leave room for nature’s will emerges above all as a precise life choice. Piero’s attention to natural data makes him an observer with a predilection very similar to Leonardo’s. Vasari also alludes to it: “he sometimes stopped to consider a wall where at length fusse been spat on by sick people, and he drew from it the battles of the horses and the most fantastic cities.” Thus Leonardo’s passage in his Treatise on Painting is recalled, where he speaks of a stain left “by a sponge full of different colors.” And “in such a stain one sees the various inventions of what man wants to look for in that.” The solitary attitude kept Piero di Cosimo at the corners of the Florentine art scene until his forties, although he was active and worked for the most illustrious families. Above all, he was linked to the Pugliese family, which commissioned from him the Saint Louis Altarpiece and the panels of the Prehistory cycle.

In 1492 the Magnifico died, Savonarola raged with his sermons, and the brief republic of Pier Soderini appeared. The Pugliese’s were anti-Medicean and sympathized with the friar’s sermons; Francesco del Pugliese, twice prior of Florence, would be exiled in 1513 after ill-temperedly appealing to Lorenzo de’ Medici in public. In his later years, the painter was plagued by pathological manias and obsessions: Pontormo’s diary recounts that his workshop was deserted and that Andrea del Sarto could no longer stand his extravagances. A friend of solitude, Piero became increasingly shy and, especially in old age, frustrated that he could no longer paint, “venivagli voglia di lavorare, e per il parletico non poteva. Et entrava in talmente angera, che volere sgarare le mani che stare fermo, e mentre che e’ borbottava, o gli cadva da poggiare o veramente i pennelli, che era una compassione.”

About the chronology of Piero’s works many debates subsist. Since there are so few documents about him, it is difficult to orient oneself in his production. Even Vasari, in his biography, often willingly yields to anecdote without offering much indication of his artistic growth. Generally, the chronological breakdown of works has always relied on punctilious comparison with the Florentine culture of the time, between 1480 and 1520. Considering Piero’s fickle and often unpredictable whimsical soul, however, the method is weak, and it is not uncommon for critics to arrive at far-flung conclusions on some objects. The case of the portrait of Bella Simonetta, whose dating divides critics between 1480 and 1520, is emblematic. The woman’s profile, with its clear, marble complexion, stands out from a mound of dark clouds, assuming a relief similar to that of an ancient cameo. This solution of clouds, posed to generate a tonal contrast, was already proposed by a rookie Piero di Cosimo, to be precise in the scene of The Army of Pharaoh submerged in the Red Sea, in the Sistine Chapel. For this reason, the portrait could refer to a time close to the Roman sojourn (1481-1482). Overall, the group of youthful works is the one in which the influences of Florentine art of 1480-1490 are discernible: in the Montevettolini Altarpiece one glimpses the still-acerbic reflections of Filippino Lippi and Leonardo, as well as in the San Giovannino in New York. Still young is the Piero of the Saint Louis Altarpiece, commissioned by the Pugliese family, where the pathetic and refined forms of the embrace of the two protagonists recall Filippino. Instead, Piero thinks of the fullness of Ghirlandaio’s Madonnas when he made the Madonna and Child, which is now in a private Florentine collection.

The paintings mentioned do not touch on 1490: the same is true of the Visitation with Saints Nicholas and Anthony Abbot, now in the National Gallery in Washington. With its limpid and squillant colors, this panel painting is particularly significant because it marks a watershed in Piero’s production, bringing with it confirmation of the painter’s contact with the Nordic milieu. Already prone to the study of the “oddities” of nature, extremely fascinated by the subtleties born of chance, here Piero sharpens that Flemish naturalism of his by accentuating the Nordic atmosphere in the architecture of the houses, the rendering of the tree and the birds. The light is stark and the reflections become glazed, the natural truths are exaggerated. It is, this, a trend that will become increasingly consolidated. One senses the comparison with Hieronymus Bosch, but it was the knowledge of Hugo Van der Goes’ Portinari Triptych that must have marked his pictorial evolution intensely.

The great attention given to detail must have implied a slow pace in the artist’s modus pingendi. So much so that in forty years of activity only about fifty paintings can be attributed to him. Florence, in the last decade of the 15th century, was experiencing its strong period of crisis, and meanwhile an elderly Botticelli, Lorenzo Credi, and Ghirlandaio remained, and Perugino and Signorelli also practiced there. In the midst of political turmoil, Piero continued to remain isolated and led his life with a light heart, remaining close to the Pugliese family. For their family palace, he painted a number of “small-figure stories” identified by critics with the panels now in Oxford and New York, backsplashes of a Florentine room in which the Stories of Primitive Mankind were narrated(read a more in-depth discussion here). Nothing at the time came close to such a vivid imagination. Piero narrated a tender and wild nature, making timely recourse to the symbolic use of fire. In these two executions it is easy to understand the lifestyle embraced by the painter, for whom civilization meant a good compromise as long as man remained in touch with nature. An excellent interpretation of these panels is offered by Erwin Panofsky in 1939. Commissions of this kind, of reduced surface area and profane content meet the "abstract and dissimilar" ingenuity of Piero, who thus succeeds in venting his great imaginative capacity, stepping outside the box and without abandoning his sought-after naturalistic component. Something that was more difficult to pursue in the large altarpieces of religious subjects, often requested by the commissioning families.

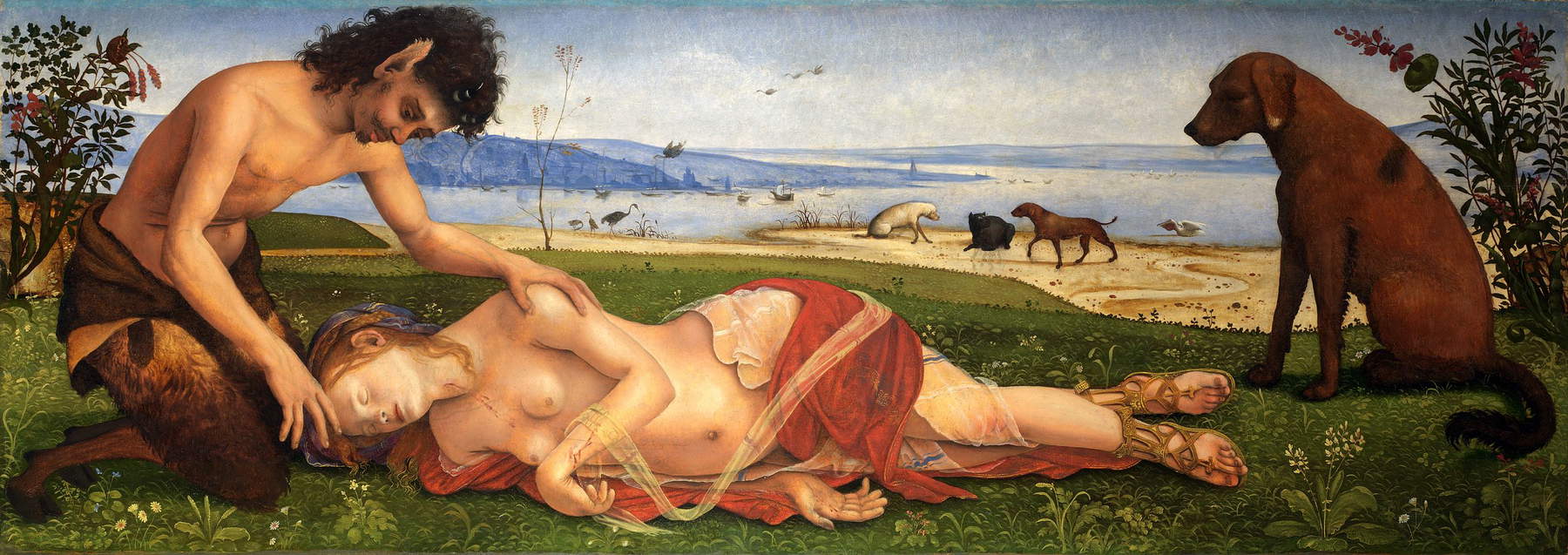

Alongside a family with accentuated republican tendencies, Piero di Cosimo had sparse encounters with the more strictly Medici milieu, to which only his friendship with the architect Giuliano da Sangallo, evidenced by a portrait, brought him closer. On the threshold of the sixteenth century, Piero di Cosimo is confronted with Bartolomeo della Porta, Leonardo (who returned to Florence from 1500 to 1506), and Raphael. With the latter there will be a fertile exchange on the consideration of light, but the evolutionary breakthrough occurs mainly because of the dialogue with Leonardo. Vasari looks at Piero di Cosimo as a kind of instinctive and “plebeian” Leonardo: from da Vinci’s genius, precise quotations can be discerned in Piero’s works datable to the first decade of the new century. In the angel of the Madonna Cini, Federico Zeri identified the model in the exaggerated twist of da Vinci’s Leda. Again Piero looks to Leonardo and his Battle of Anghiari when he composes the Struggle between Centaurs and Lapiths, in those twisted and intricate forms of the bodies, in the convulsive entanglements. It is, however, in one of Piero’s finest paintings that Leonardo’s contribution can be clearly perceived: in the Death of Procri, Piero can ample leisure in illustrating Ovid’s Metamorphoses. Of uncertain date (last decade of the century - 1510), here the Flemish root is diluted in Leonardesque blue and shaded gradations. The horizon loses texture, oblivious to the details of the Visitation, and degrades into the veil of atmosphere.

In the last period we find a kind of return to order. The Pietà of Perugia and the Borgo san Lorenzo altarpiece bring Piero into the groove of religious production, which is a genre little akin to his temperament. The imposed iconographies must have weighed heavily on him since, as soon as he had the chance, he would twist them. In his late activity, Piero rediscovers a different rigor, bordering somewhat on clumsiness as in the Perugia Pietà where the scheme (derived from Perugino) is more present. The same happens in the mythological painting: with the backs depicting the Stories of Prometheus, the composition returns symmetry, an almost mirror-like correspondence of gestures. The landscape becomes simplified, the colors fade into lower tones. At the end of his life, the artist seems attracted to the new masters, the neo-Leonardo wake marked by Andrea del Sarto and a young Rosso Fiorentino. But now he is clumsy, no longer has that drive to subvert, his brushwork has lost vigor.

Piero in his early days can be seen in Rome, in the details and landscapes of the frescoes in the Sistine Chapel. Still in the capital, at the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica, there is a splendid Magdalene giving evidence of one of the highest solutions of Piero’s portraiture. In Perugia is the Pietà of his last years, while the Uffizi houses Perseus and Andromeda and theIncarnation of Jesus. Also in Florence, the Museo degli Innocenti houses Pugliese’s Sacra Conversazione. In Rome, the Gallerie Nazionali d’Arte Antica preserves St. Mary Magdalene (read more here). Some of Piero’s works can be found at small towns in Tuscany: in Montevettolini (near Pistoia) you can admire the Montevettolini Altarpiece, in Fiesole is theImmaculate Conception, and the parish church of San Lorenzo in Borgo San Lorenzo houses the Madonna and Child with Saints John the Baptist and Thomas. Outside Italy, the Condé Museum in Chantilly houses the portrait of La Bella Simonetta.

The majority of Piero di Cosimo’s works, and among the most beautiful mentioned above, are found in English-speaking countries: the fortunes of this artist were raised especially after André Breton, in the first half of the 20th century, redeemed him from oblivion by counting him among those artists who had a magical, abstract vision of art. So the Battle of the Centaurs and the Lapiths, the Death of Procri are at the National Gallery in London. The altarpiece with the Visitation is at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, the St. John the Baptist is at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

|

| Piero di Cosimo, life and works of a diverse artist |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.