Imagine a crowd of Parisians on July 14, 1789 as they stormed the Bastille, a now almost disused prison. We then think of all that followed that event, which represented the ultimate breaking point between the people and the absolute monarchy, beginning the French Revolution. But what prompted the Parisians to storm the Bastille?

The crisis was triggered a few days before July 14, 1789, when King Louis XVI (Versailles, 1754 - Paris, 1793) dismissed his finance minister, Jacques Necker. The news of his removal caused an immediate upheaval in public opinion. The reason? Necker, known for his moderate positions and willingness to dialogue with the National Assembly, was seen as a trusted figure by much of the population. His exclusion from the government was therefore interpreted as an unmistakable sign of the king’s attempt to authoritatively reverse the process of constitutional transformation that had begun in the preceding months. In the days leading up to July 14, about three thousand people gathered in the gardens of the Palais-Royal. They paraded through the city displaying black flags, dark coats and hats. In the center of the procession, a bust of Necker, covered by a veil, symbolized mourning for the minister’s downfall.

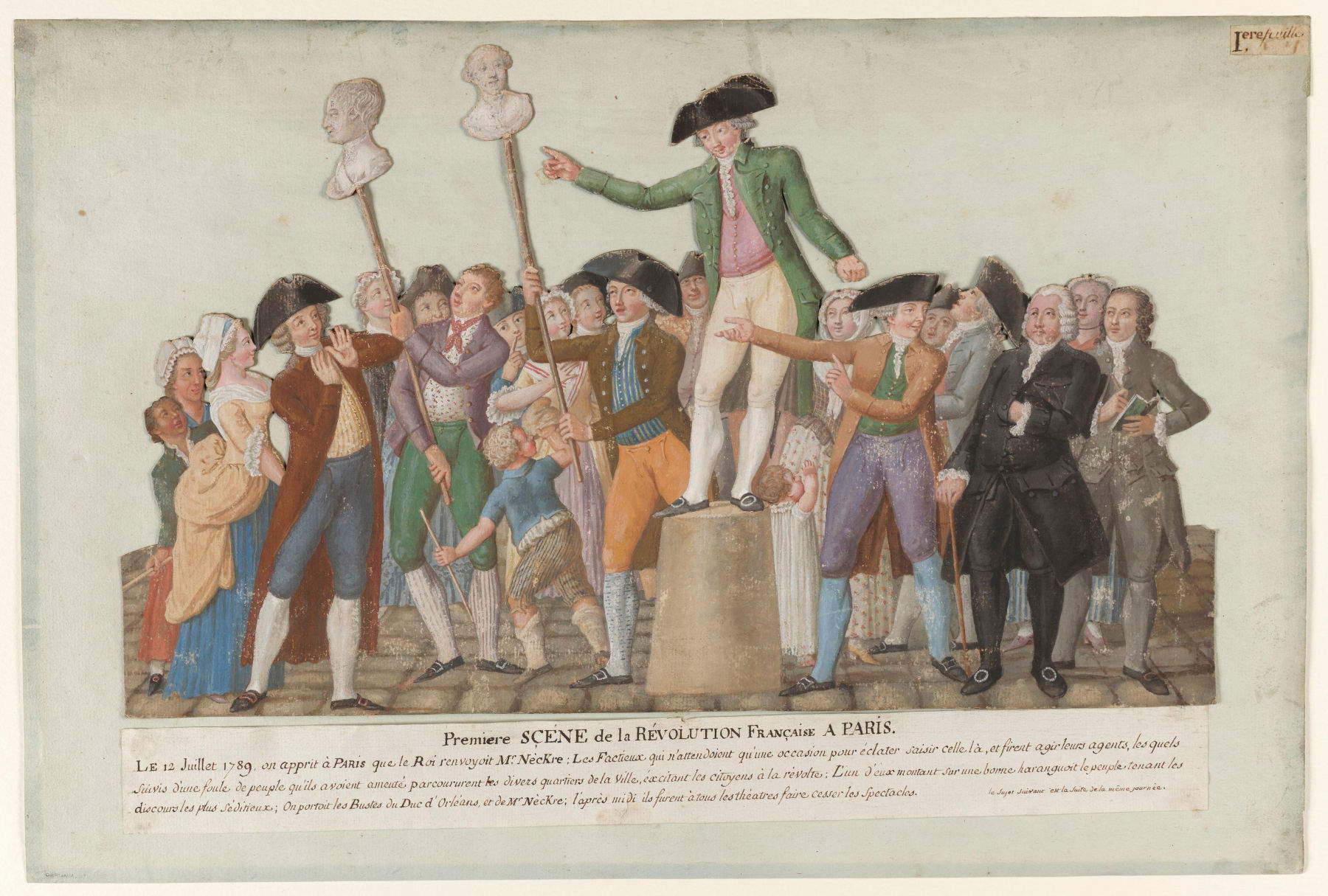

We were left with evidence of this by Jean-Baptiste Denis Marie Lesueur, who between 1789 and 1790 produced a work now in the Musée Carnavalet in Paris. Executed in mixed media on paper and cardboard, using gouache, the work takes the title First scene of the French Revolution in Paris, displaying the busts of the Duke of Orleans and Necker, July 12, 1789. In the center of the image, a compact crowd advanced along the streets of Paris carrying two busts hoisted on improvised pedestals. These were in fact the effigies of the Duc d’Orléans and Jacques Necker, finance minister who had just been dismissed by Louis XVI. The two figures, perceived as favorable to reform and close to the Third Estate, were commemorated as heroic figures by the people in revolt.

The atmosphere in Paris was thus thick with tension, and protesters began to utter new terms such as “liberty,” “constitution,” “nation,” and “citizens.” They were the words of an emerging political lexicon that quickly challenged the established order. At the same time, Paris was experiencing a time of deep economic crisis. The previous year’s harvests were poor, with soaring bread prices and widespread famine as a result. The ranks of the poor and beggars swelled, and a sense of insecurity grew in the population fueled by alarming rumors of impending military repression.

How did Louis XVI move in all this turmoil? He decided to converge troops around the capital, an operation that, according to some sources of the time, was not limited to the occupation of the city, rather could culminate in large-scale destructive action. That’s it: the movements raised paranoia, generated mass hysteria, and caused the population to mature in the belief that a so-called coup d’état was being prepared. On the morning of July 14, 1789, the people of Paris rose up and invaded the streets as the tension built up over the previous days exploded and rumors spread that some thirty thousand guns were being kept at theHôtel des Invalides, a military facility located west of Paris. Thousands of citizens then headed for the site, which was easily stormed. The mob took over the arsenal and came out equipped with guns and twelve cannons.

Many historians regarded this moment as decisive: the taking up of arms marked an irreversible turning point. Probably from that moment Louis XVI lost military control over Paris and with it absolute power. But the population’s attention did not stop at the Hôtel des Invalides. A few hours later, another mass headed for the Bastille, toward the other side of the city, with the aim of seizing the gunpowder stored there. Although the prison had long since ceased to be a major center of operations, it retained a strong symbolic value. As a state prison, it housed political opponents, intellectuals, libellists and other figures disliked by the monarchy in the past. A few names? The Marquis de Sade, Nicolas Fouquet and Voltaire. Attacking the Bastille therefore meant attacking the very center of arbitrary power. Visually, several works came to our aid.

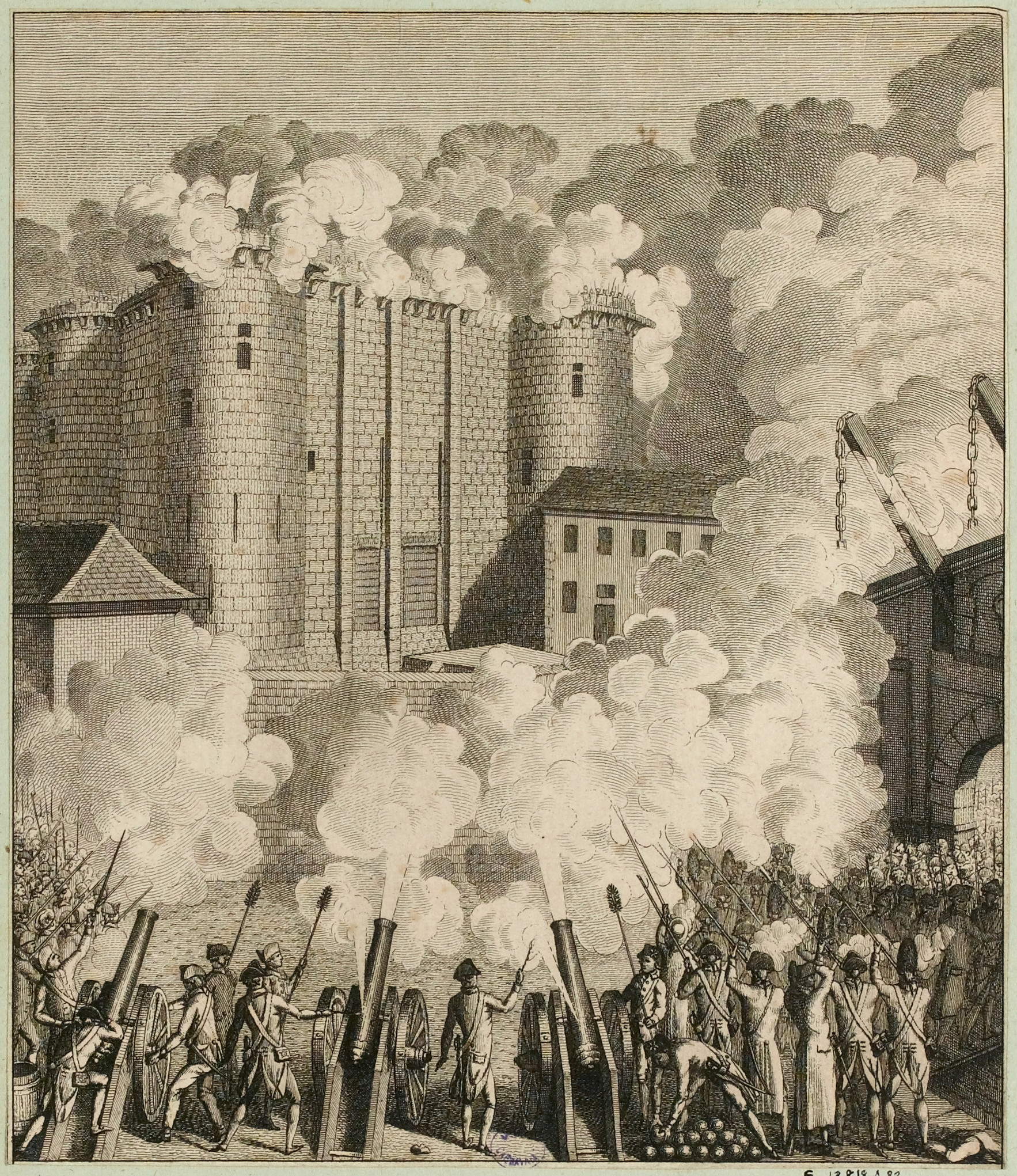

Made between 1784 and 1794, the etching attributed to the Dutch School returned the first attack on the Bastille. The scene depicted the beginning of the popular assault on the fortress, once located at the point where the 4th, 11th and 12th arrondissements of Paris converge today. With a meticulous stroke, the image captures the armed mob, the gunfire, and the compact mass of the prison, which dominates the composition as an emblem of declining authority.

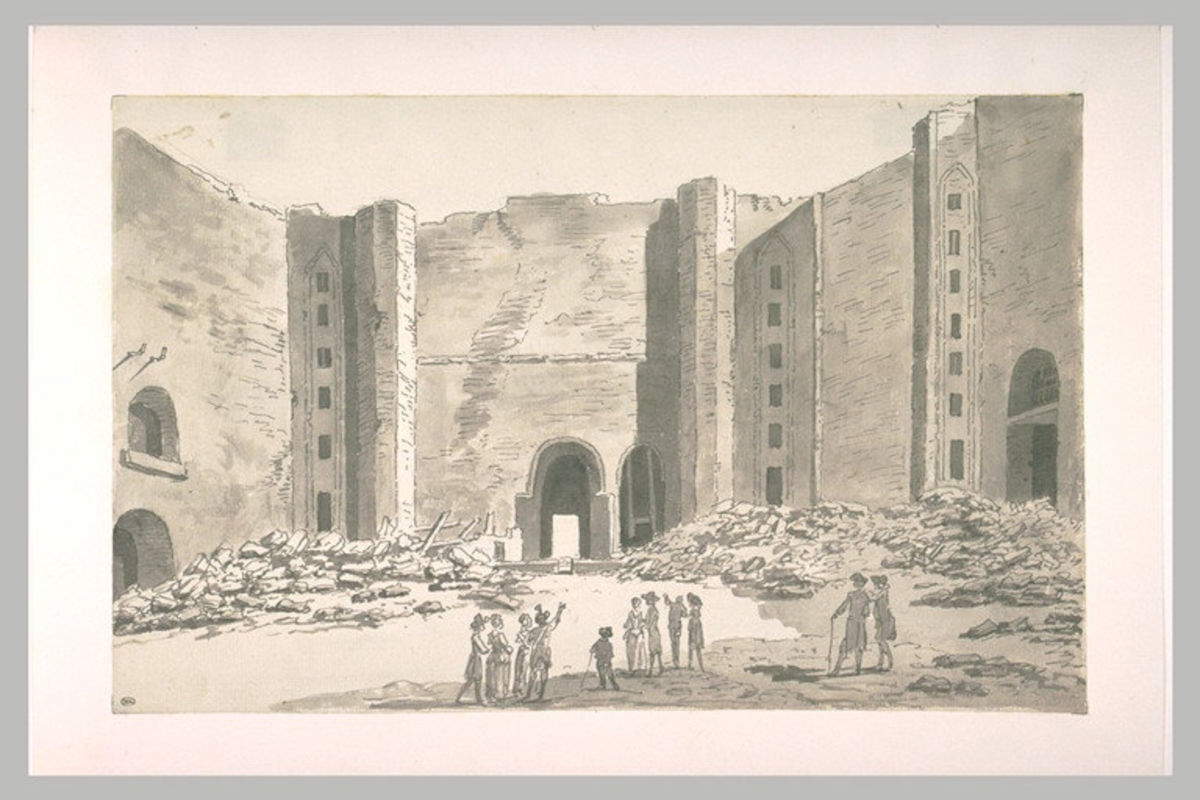

Jean-Pierre Houël’s watercolor, made in 1789, also presents a theatrical depiction of the storming of the Bastille. The work captures the drama of the event as the crowd besieged the fortress. The composition is dominated by the mass of insurgents who, armed with rifles, pikes and cannons, approach the prison ramparts menacingly. From the battlements can be glimpsed the mouths of responding cannons, while plumes of smoke suggested the exchange of shots between attackers and defenders. Houël pays great attention to the architectural details of the Bastille, portraying it as an imposing structure, looming over the crowd but already threatened in its integrity. Jacques-Louis David also devotes a study to the prison symbolic of absolutism. His gray lavis drawing, now housed in the Louvre in Paris, returns a stark and thoughtful vision of the fortress.

After hours of fighting and failed negotiations, in the late afternoon of July 14 Governor Bernard-René de Launay ordered the gates to be opened and the garrison to surrender. Despite the surrender, the governor was captured by the mob and lynched on the way to the Hôtel de Ville. The storming of the Bastille ended with the capture of the fortress and the liberation of seven prisoners, four forgers, two men deemed insane and an aristocrat who had fallen out of favor with his own family, the Count of Solages. To storm the Bastille, the inhabitants of the Saint-Antoine quarter faced a garrison of eighty veterans of the Invalides and about thirty Swiss soldiers. Louis XVI, deeply shaken, recalled Jacques Necker to the government in an attempt to calm tempers, but the wave of protest now extended far beyond Paris, sweeping through the major cities of France. After the conquest, the systematic destruction of the building began, which was completely demolished until only an empty square was left in its place.

In contrast, a narrative and popular approach emerged in Jean-Baptiste Denis Marie Lesueur’s gouaches, such as Demolition of the Bastille (1789/1794), made with cut-out silhouettes applied on a blue background. The technique, reminiscent of collectible military figurines, was combined with a lively and direct style capable of demonstrating the collective spirit of the time. Lesueur constructed a kind of visual chronicle of revolutionary events, mixing naiveté and irony, enthusiasm and imperfection. His images, rather than aspiring to an academic representation, still return the immediate emotion of the historical moment, with the urgency of what we might call a popular diary.

True, the storming of the Bastille represented the beginning of the Revolution, but also the end of an era. The absolute power of the monarchy was challenged by collective and spontaneous action, the citizens of Paris took up arms on their own initiative, determined to oppose what they perceived as a return to repression and authoritarianism. In French collective memory, July 14 thus became the birth date of the Republic, although the monarchy survived for a few more years. In 1880, almost a century later, the date was officially adopted as a French national holiday. In any case, beyond the celebrations, there remained the impact of a day that, through a combination of political crisis, social tension and popular mobilization, the storming of the Bastille overthrew an entire system of power and inaugurated one of the most tumultuous seasons in European history.

|

| The storming of the Bastille in art: what happened on July 14, 1789? |

The author of this article: Noemi Capoccia

Originaria di Lecce, classe 1995, ha conseguito la laurea presso l'Accademia di Belle Arti di Carrara nel 2021. Le sue passioni sono l'arte antica e l'archeologia. Dal 2024 lavora in Finestre sull'Arte.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.