Today, if we think about it, it is not unusual to come across female art gallerists: they welcome visitors to their galleries, in Italy as well as abroad, on a par with their fellow gallery owners, and even at the many art fairs that take place throughout the year in various Italian cities and around the world they are not a rarity. Fortunately, the working world has evolved in this sense, and a profession that, no farther back than the last century, was considered a primarily male prerogative has now become universal. The most famous example of a gallerist and collector, still seen as an exception for the era in which she lived, the twentieth century, is surely the American Peggy Guggenheim, who at only thirty-nine opened her first art gallery in London, extending then after four years to New York, and then finally falling madly in love with Venice so much that she moved and relocated her entire collection here from 1949 until her death in 1979. And during all these years, from the beginning of her career until her death, she was a true patron, constantly surrounding herself with art and famous artists but also those hitherto unknown, contributing herself, through her, temporary exhibitions and acquisitions, to make many of the latter known; to give a few examples, Mark Rothko, Robert Motherwell, and Jackson Pollock, the most striking case, but also Hans Arp, Constantin Brâncuși, Emilio Vedova. Before the world-famous Peggy Guggenheim, however, the twentieth century saw another art dealer, collector, and patron who surrounded herself with art and artists throughout her existence, contributing for nearly forty years to the discovery and success of painters and sculptors who later entered the Olympus of art history: Berthe Weill (Paris, 1865 - 1951).

However, despite her fundamental role in the spread of modern art and her great influence on the art of the period, her story has been unjustly almost forgotten or at any rate remains little known to this day. It is therefore in order to make the general public rediscover the figure of this important art dealer who anticipated the times, in an era dominated by men, that the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris retraces in an articulate exhibition of about one hundred works, entitled Berthe Weill. Galeriste d’avant-garde (“Berthe Weill. Galleriste d’avant-garde,” curated by Sophie Eloy, Anne Grace, Lynn Gumpert and Marianne Le Morvan) and on view until Jan. 26, 2026, her activity and career, clearly revealing both her personality and her crucial contribution. “It is an exhibition that aims to restore her to her rightful place,” in the words of Musée de l’Orangerie director Claire Bernardi, and the intent, in the opinion of the writer, is well accomplished. But let us trace her story by following the flow of the exhibition and the works on display.

Born in Paris on Nov. 20, 1865, into a modest Jewish family of Alsatian descent, Berthe Weill began her journey in art at a very young age, learning her trade from her cousin, the print and picture dealer Salvator Mayer, through whom she had the opportunity to get to know both the leading figures of the Parisian art scene and collectors. After Mayer’s death in 1896, Berthe opened her first antique store in the bustling Pigalle district at the foot of Montmartre, where many avant-garde artists lived and worked in precarious conditions. Right from the start she demonstrated not only artistic but also political audacity: in 1898, in the midst of the Affaire Dreyfus, she took a stand by displaying Henry de Groux’s large canvas Zola aux outrages in her window, a gesture that caused her threats and insults, thus immediately revealing her combative nature. The early years were economically difficult: she had to make the business of her workshop varied, selling books and exhibiting engravings alongside works by illustrators and caricaturists in order to bring in more income.

In 1901, at the age of thirty-six, with the help of Catalan merchant Pere Mañach, who was promoting the young Spanish generation, she transformed her workshop into Galerie B. Weill, hiding her first name, probably to disguise the fact that a woman was running the business. She inaugurated it on December 1. Her keen sensibility immediately emerged: Mañach had introduced her to Pablo Picasso who had just arrived from Barcelona, and Weill not only bought his works but sold about fifteen of them before the artist even held his solo show at Ambroise Vollard’s gallery. She was in fact his first dealer. A number of Picasso paintings that she bought are on display, including La Mère, Nature Morte and Chambre bleu, the latter work belonging to the “blue period.”

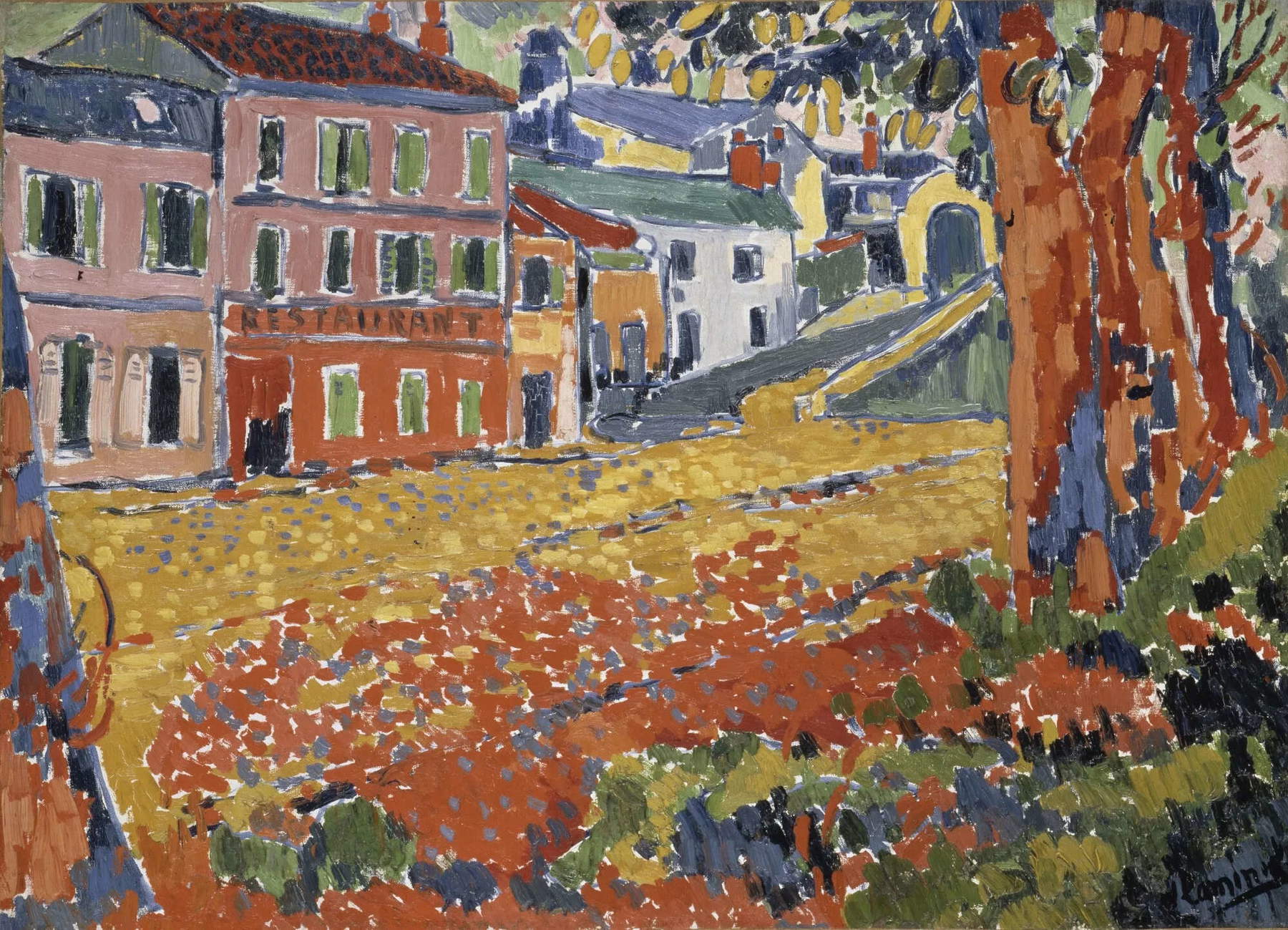

She became known as a discoverer of up-and-coming talent, selling in April 1902 for the first time a painting by Henri Matisse in her gallery (Matisse’s Première nature morte orange and Le lit exhibited here) and befriending Raoul Dufy (present here, Paysage de Provence and La Rue pavoisée). Her determination was “unwavering,” as she called it in her memoirs published in 1933 under the title Pan! dans l’oeil... Ou trente ans dans les coulisses de la peinture contemporaine 1900-1930, from which are taken the most significant sentences that the gallerist wrote and which serve as the titles of the different sections of the Paris exhibition.

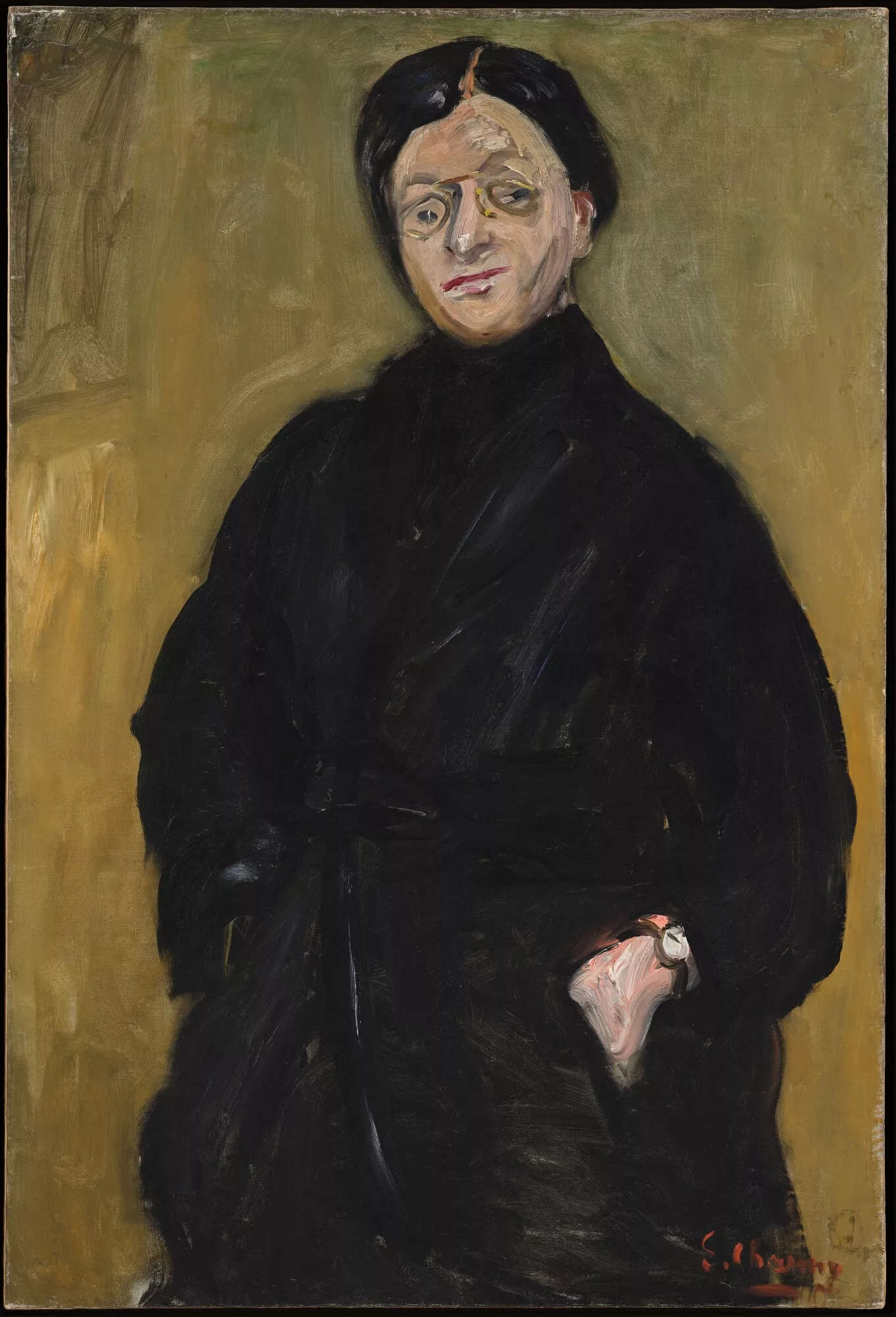

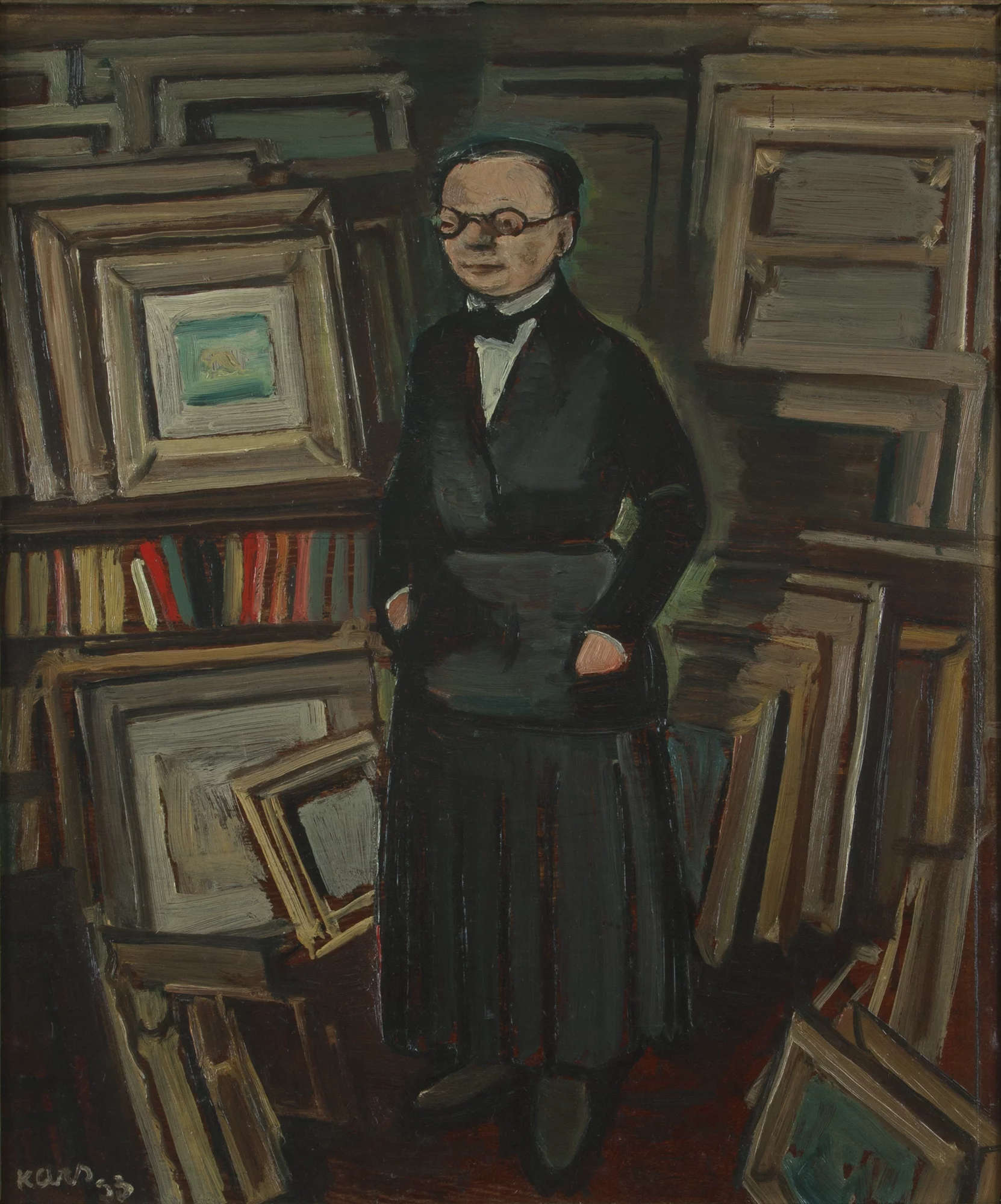

Galerie B. Weill also played an important role in the recognition of Fauvism. In fact, as early as 1902, before their consecration-scandal at the 1905 Salon d’Automne because of their overly bright colors and simplification of forms, the dealer regularly hosted exhibitions by Maurice de Vlaminck, André Derain, Albert Marquet and a group of Gustave Moreau’s pupils gathered around Henri Matisse. Examples on display are paintings by Raoul de Mathan, Pierre Girieud, and Kees Van Dongen. He then discovered at the Salon des Indépendants in 1905 the talent and independence of the painter Émilie Charmy, who in twenty-eight years exhibited in the Galerie B. Weill thirty times, with whom she formed a lifelong friendship (a self-portrait of her and a portrait with hands in pockets and wristwatch that the artist made of her patron and friend Berthe is exhibited here).

His support for the avant-garde did not stop there: he also gave space to Cubism, despite difficulties in the era when aesthetic dispute often masked nationalist considerations. In fact, Weill supported from the outset many artists whose work included a Cubist period, exhibiting before the World War almost all the main exponents of Cubism, and organizing, in 1914, solo exhibitions for Jean Metzinger and Diego Rivera (his Eiffel Tower is shown here), whose works can be seen in the exhibition alongside those of André Lhote, Louis Marcoussis and Alice Halicka, whom Georges Braque called “Cubists.”

In the early decades of the 20th century, Paris established itself as an international hub for artists from Europe, from the territories of the former Austro-Hungarian Empire to the United States. Berthe Weill’s activity fit into this dynamic context, contributing decisively to the emergence of often marginalized artistic personalities marked by conditions of economic precariousness and forms of social exclusion. Animated by an independent curiosity and a personal outlook, Weill chose artists without adhering to theoretical agendas, but rather relying on her own sensibility and the quality of the works. In exhibition after exhibition, she also opposed a conservative view of French art, often steeped in nationalistic, xenophobic and anti-Semitic closures.

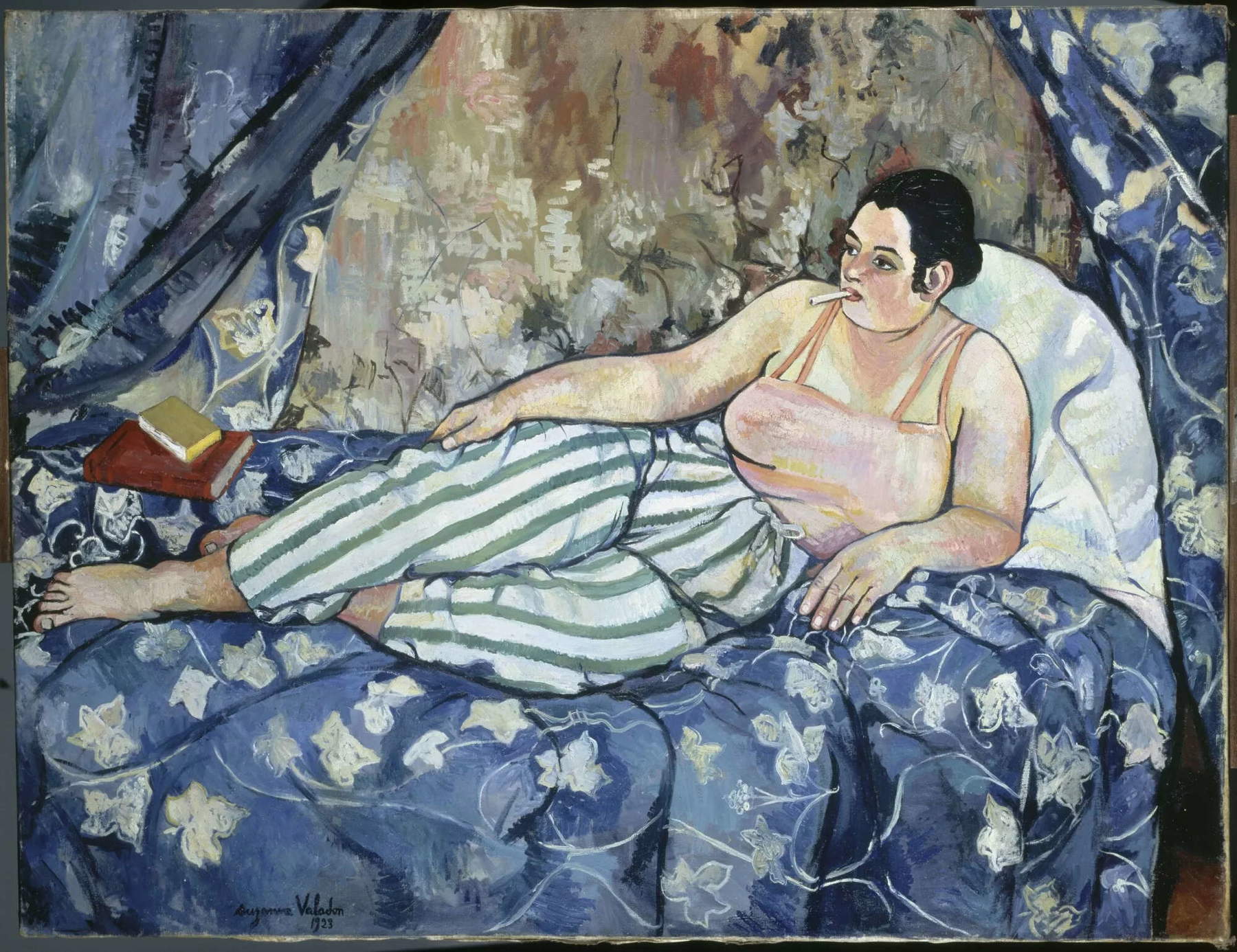

Above all, however, his attention to young artists remained steadfast over time, translating into an ongoing commitment to promoting them through dedicated exhibitions. Thus we see in this section a beautiful nude by Suzanne Valadon (as a woman, Weill had a special concern for women artists), Raoul Dufy’s Vie en rose , which the artist made in 1931 to celebrate the 30th anniversary of Galerie B. Weill, and paintings by the Bulgarian painter Jules Pascin, who after their meeting in 1910 exhibited him in her gallery twenty-three times.

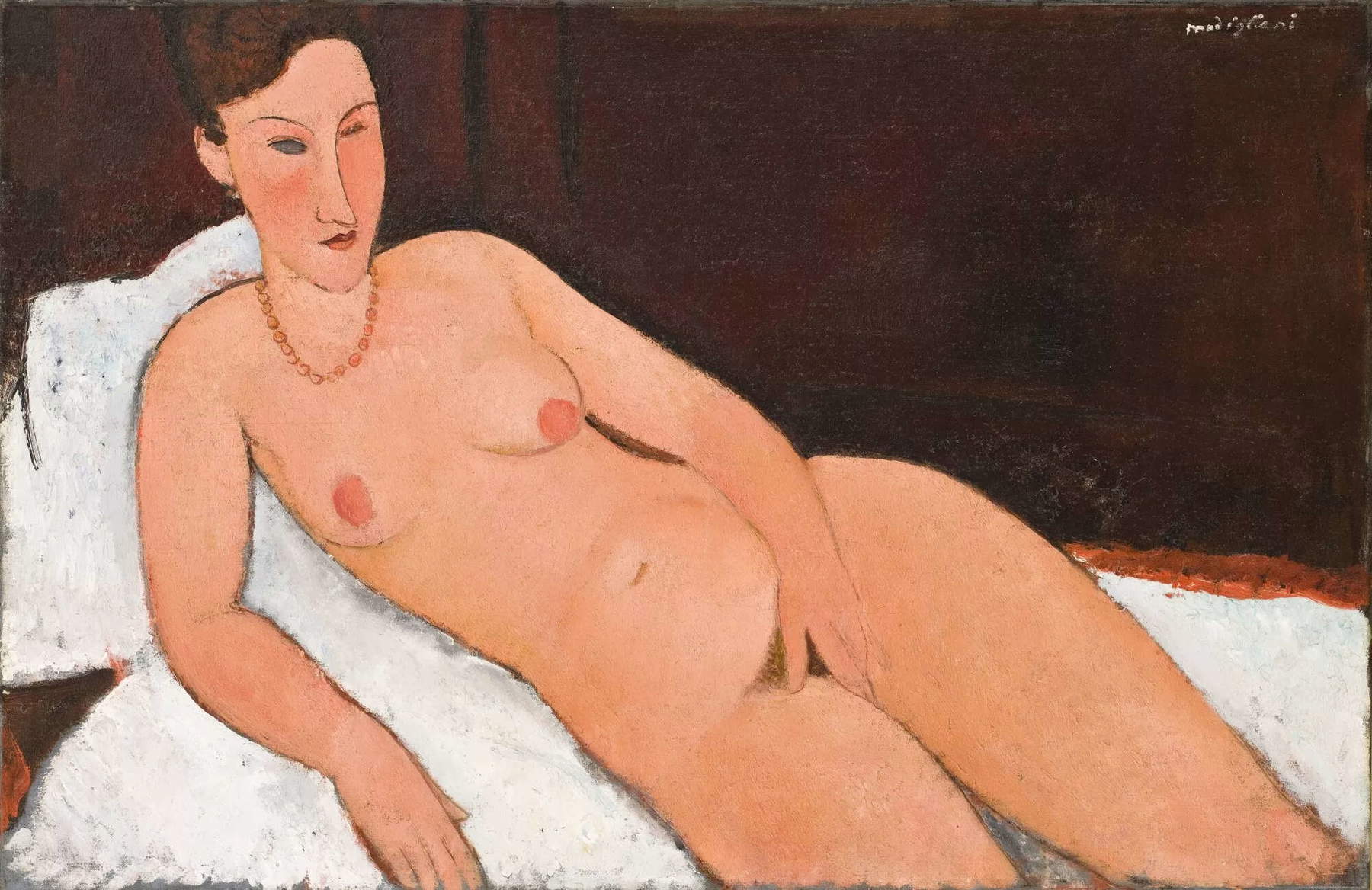

In 1917, the gallery owner went into debt to move to a larger space. It was in this new location, at 50 rue Taitbout, that one of the most sensational events of her career occurred: at the urging of the Polish-born poet Léopold Zborowski, she organized the only solo exhibition devoted to Amedeo Modigliani while the Leghorn painter was still alive. The exhibition, which featured thirty-two works including four nudes that later became famous, was interrupted by a scandal because of pubic hair visible in the paintings. The local police commissioner intervened, ordering them to “enlever toutes ces ordures!” (“remove all this filth!”) for “outrage against modesty.” Despite the outcry, the exhibition was a commercial failure, but Weill, admiring Modigliani’s painting, bought five works to support it. There are two paintings by Modigliani in the exhibition, including a bold nude of a woman lying on a bed with a coral necklace around her neck, but it is not known exactly whether this was actually among the four nudes presented at the exhibition mentioned, due to the lack of accuracy of that exhibition’s catalog. Also on display is Suzanne Valadon’s La Chambre Bleu, another painting that went against the conventions of the time for its modernity and which Weill exhibited in his gallery in 1927. He then appreciated the painting of Odette des Garets, Georges Émile Capon and Georges Kars, as evidenced by their works exhibited here.

In 1924 he organized his first group exhibition, which from then on would be held every end of the year on a specific theme. She celebrated two years later her twenty-five-year anniversary with a large masquerade party, documented here by a giant photograph depicting the gallery owner, recognizable by the monocle she wears, in the midst of her artists and the many guests, but the Wall Street crash of 1929 forced her to put her personal collection up for sale. In the late 1930s she decided to exhibit artists she had not yet promoted, such as Otto Freundlich (here his 1939 Composition, the year the painter was interned and four years later killed in a death camp), and shifted her focus to abstraction.

His 40-year career was dramatically interrupted by history: to circumvent laws against Jews, which forbade them from running businesses, he put a friend in charge of the gallery, before its final closure in 1940. Weill, after fracturing her femur in 1941, lived in hiding and in great poverty, probably in the studio of her friend Émilie Charmy. It was not until 1946 that a large charity auction was held, with over eighty works donated by friends, artists and even competing gallerists, to lift her out of poverty. In 1948, she was made a Knight of the Legion of Honor. She disappeared on April 17, 1951, at her home at the age of eighty-five. In forty years, Berthe Weill supported more than three hundred artists and organized hundreds of exhibitions to contribute to their cause. Despite this, her story has today almost entirely fallen into oblivion. She was an avant-garde gallery owner who devoted forty years of her life to supporting the artists of her time with unparalleled enthusiasm and perseverance, always keeping in mind her purpose: “Place aux jeunes,” she said.

Dedicating an exhibition like the one at the Musée de l’Orangerie to her therefore means returning the proper tribute to a pioneer who fought on the front lines in favor of art and artists in an all-male era, with the hope that her rediscovery will not yet be overshadowed.

The author of this article: Ilaria Baratta

Giornalista, è co-fondatrice di Finestre sull'Arte con Federico Giannini. È nata a Carrara nel 1987 e si è laureata a Pisa. È responsabile della redazione di Finestre sull'Arte.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.