We tend to associate Giovanni Segantini’s painting with alpine landscapes, snow, and mountains. Angelo Conti, in Beata Riva, a fundamental treatise on aesthetics, said that Segantini was “the revealer of the mountain,” because “no one like him ever had a sense of the mountain, no one knew how to represent what that the mountain expresses with its august stillness, no one like him has felt the silence that surrounds it, has known the aspiration of its peaks, has heard every word of its conversations with the wind, with the night, with the dawns, with the fruitful clouds and with the fecundating rivers.” The artist is a human being who sees reality in a different way than everyone else does.Regardless of what can be said about Segantini, one could start from this observation to begin to reread everything that has been said about him, and often with opposing interpretations. For an Angelo Conti who saw in his mountains a form capable of fixing “the ideal scheme of what Giovanni Segantini’s art has stopped in the definitive line of style,” and thus a sort of tangible emanation of an absolute and eternal idea, there were legions ofother critics who, on the contrary, believed that those mountains, even if they were to a certain extent transfigured, transformed through the lens of symbolism that Segantini would practice in the last portion of his existence, were nevertheless an expression of a frank verism never forgetting the Lombard foundations on which the artist had built his painting. In presenting the major exhibition that the Museo Civico of Bassano del Grappa is dedicating this year to Segantini, curated by Niccolò D’Agati, director Barbara Guidi fixes the mountain as perhaps the central element for reading this new exhibition occasion, making her own a consideration by Francesco Arcangeli who had reiterated the significance of the Trentino painter’s isolation: in his opinion, in Segantini’s isolation should be seen as an attempt to “get out of the civilization long elaborated in the cities and to find again a lost innocence,” following a call similar to the one that had brought Van Gogh to Provence and Gauguin to Tahiti. The truth is that, as much as Segantini cannot be considered a naive painter, his mountainous isolation (for then, in reality, it was anything but: until the very end, Segantini continued to exhibit, to achieve critical and public success, and to maintain relations with critics and his gallery owners) can be read as the culmination of that renewal of the arts that had been for Segantini, for that reformatory leftover who had become one of the greatest painters in Europe, and recognized as such already by his contemporaries, a long and arduous conquest.

The public of enthusiasts who will go to see Giovanni Segantini, this is the laconic title of the exhibition that has gathered about a hundred works in the two large rooms for temporary exhibitions of the renovated Museo Civico di Bassano, will find an orderly, pleasant, combed tour, an exhibition with an essentially classical cut that follows the entire existence of the Trentino painter from his first exhibitions at Brera until 1899, the year of his death at only forty-one years of age on Mount Schafberg, in Switzerland. Admittedly, some masterpieces are missing, such as The Bad Mothers , which could not move from the Belvedere in Vienna for conservation reasons (the same goes for The Chastisement of the Lustful Women in Liverpool), or such as Alla stanga, the Rose Petal, the Two Mothers from the GAM in Milan and the Mountain Triptych, but one enjoys the view of theAve Maria a trasbordo, a masterpiece that is unlikely to be lent by the Segantini Museum in Sankt Moritz, one enjoys the chance to admire the Sole d’autunno, an important painting that was acquired a few months ago by the Galleria Civica di Arco, or even Verzée’s Ninetta, which resurfaced after seventy years of oblivion. On the other hand, those who know a little more about Italian and European art of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries will see an exhibition not devoid of unpublished and new, which could be grouped around three reasons, three elements to be identified as the pillars on which this exhibition occasion was built, certainly not rare in terms of quantity (exhibitions on Segantini follow one another almost annually), as much as, if anything, in terms of quality. First: to reaffirm the European caliber of the Arcense painter’s art. Second: to trace, also in the light of new technical-scientific acquisitions, the origins of his very particular pointillism. Third: to break down the residual stereotypes and unhinge the mythographies, those that have settled in the collective perception the image of a naïve Segantini ahead of the letter, when not that of a kind of holy man lost in the mountains and refractory to any contact with civilization. To achieve these goals, the organizers intervened with a radical contextualization, which is perhaps the most interesting and worthy operation of this exhibition, also because it was not entrusted, as is often the case, only to the catalog, but is one of the hinges around which the entire exhibition itinerary revolves, from beginning to end, indeed it is the very fabric of the exhibition, one might say.

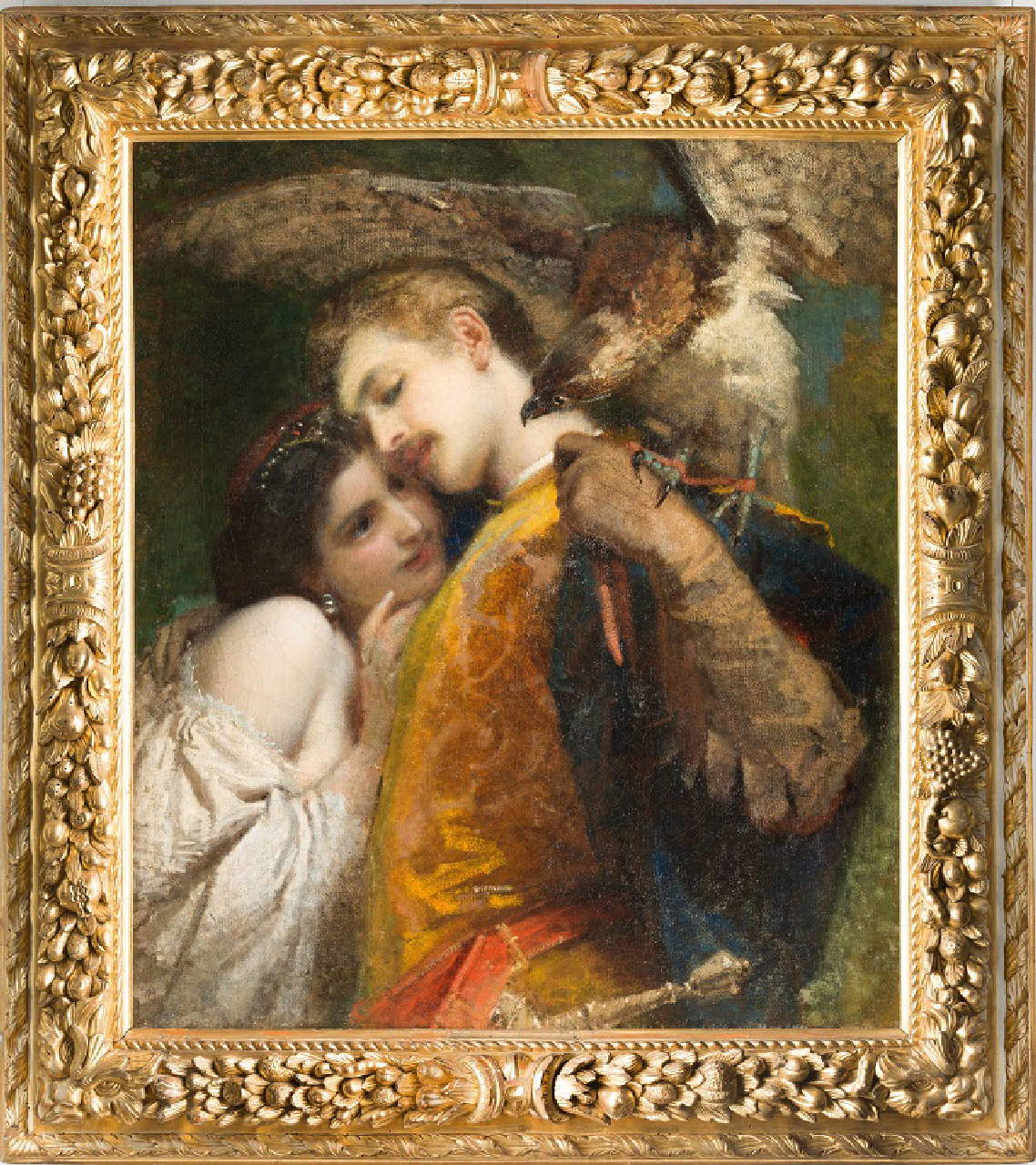

There is, meanwhile, a healthy insistence on the period of his debut, on Segantini, who, after a childhood marked by hardship, hardship, vagrancy and arrests, was taken to work as a boy by his brother Napoleone who had a photography workshop in Borgo Valsugana and thus began to mature his artistic consciousness, so much so that he made the decision, at the age of seventeen, to move to Milan to study at the Brera Academy, always supporting himself with the job of apprentice, in the store of a decorator, Luigi Tettamanzi. The Segantini of his debut is the young man who can be admired in the self-portrait lent by the Galleria Civica di Arco (which, together with the Sankt Moritz Museum, is the main custodian of Segantini’s heritage) and who portrays himself in the manner typical of the scapigliati painters, with that insistence on color used primarily to express a psychological truth: if one were to point to a particularly happy moment in this part of the exhibition, it could be found in the juxtaposition of Tranquillo Cremona’s Falconer at the GAM in Milan and Segantini’s Falconer , who, still young, paints after the example of his ideal master but producing himself not already in an imitative and pedestrian work, but in what can be considered a youthful masterpiece, original because it is more solid and at the same time looser than its predecessor, and already oriented on an entirely personal use of color as a means of expression. At the same time, Segantini explored the possibilities of portraiture by experimenting with unusual cuts and compositions (see the Ritratto di donna in via san Marco, with the girl’s melancholy face stacking the buildings of Milan painted against the light under a clear day, or theunpublished Portrait of Bice Segantini, which reappeared on the market just three years ago, with which the painter builds a sort of spiral that starts from the eyes of his companion and follows the movement of her arm and the shawl that covers her hair, with the emphasis of all the tones of white that move the composition) and deepened his ability to depict the real by trying his hand at still lifes: illuminating in this regard is a comparison of his works, beginning with the painting known as Joy of Color, a still life with eggs and poultry with an insistent emphasis on the plumage of the poor downed ducks (one of them still has congealed blood on its head) and, again, on the various gradations of white, and a’work such as Emilio Longoni’s Pigeon , which, however, though in its unquestionable, rustic, passionate adherence to the truth, lacks the symphony of modulations of a Segantini who already appears fully interested in all the developments that color can suggest to him, even in working on the humblest and most humble of subjects.

Segantini is already here. He plunged without hesitation into that artistic context marked, writes the young curator D’Agati, "by a radical reflection on language represented, on the one hand, by the vital legacy of the combative season of Lombard scapigliatura [...] and, on the other hand, by theoverbearing imposition of the colorist culture that marked the most modern outcomes of naturalism,“ and emerged from the storms of late-Romantic Milan by bringing out ”a fundamental guideline that will integrally sustain his research beyond apparent solutions of continuity: to bring color, light, line and all the compositional elements of the work understood as surface to the highest degree of expressive tension,“ even with ”works seemingly opposite in terms of results." It was only natural that such promise would be noticed by a shrewd art dealer like Vittore Grubicy, who had already met Segantini in 1879 and decided to invest in him: it was the beginning of a relationship that would last until the artist’s death and which is a constant throughout the exhibition and the entire catalog, given also the fact that only recently has an in-depth study been in-depth study of Grubicy’s papers preserved in the Mart’s collection in Rovereto, a study that began a few years ago and culminated with the major exhibition that Livorno dedicated to Grubicy in 2022, and that on this occasion also allowed for a reinterpretation of their relationship and, consequently, of Segantini’s art itself.

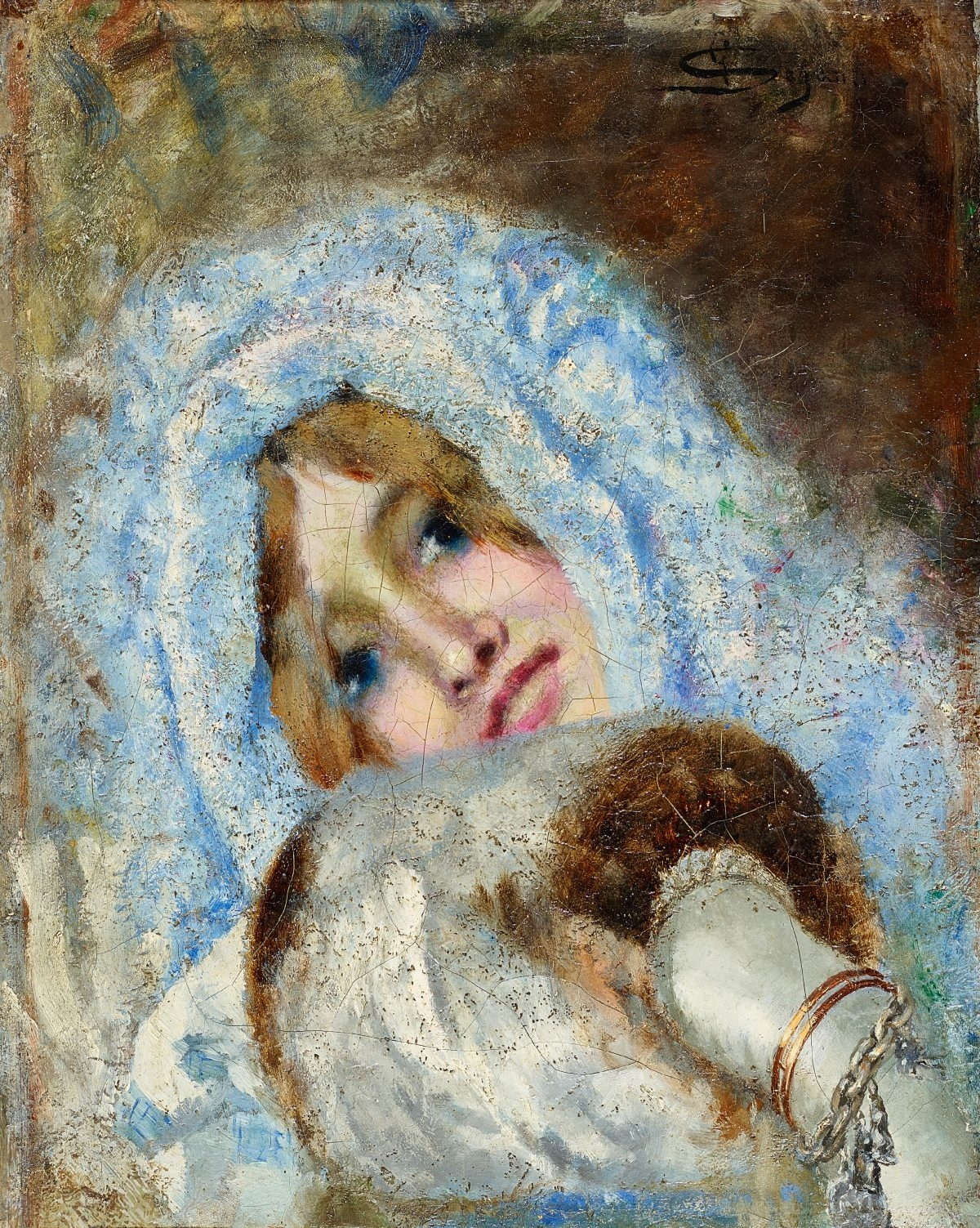

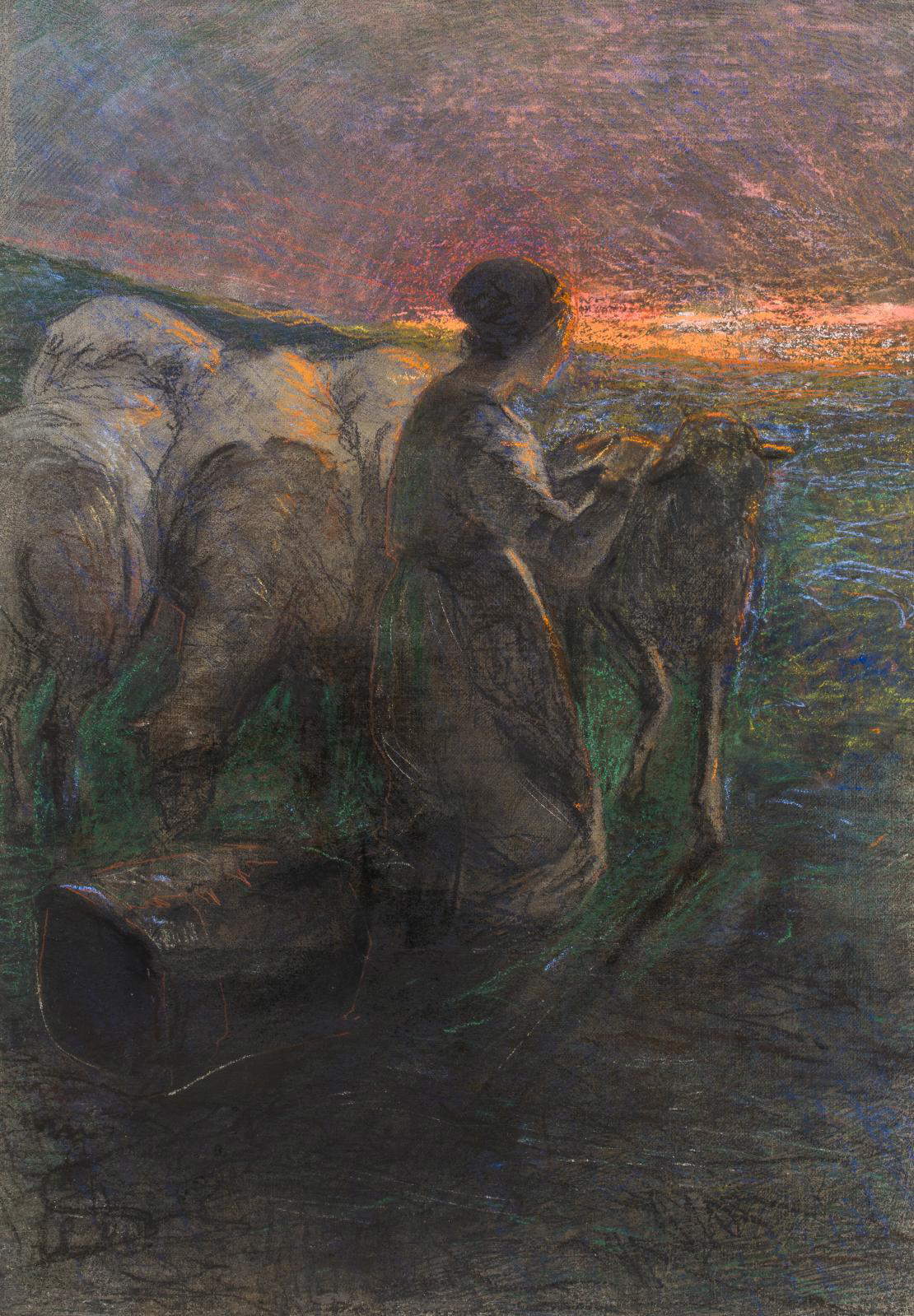

The relationship with Grubicy is retraced, first of all, with the portraits of the gallery owner’s close family circle, who would later “become a painter” for Segantini, Primo Levi l’Italico had written on the occasion of the Trentine artist’s death, to highlight how firm, solid, serious, and close the bond between the two was, a fellowship so adamantine that it had prompted Grubicy to learn to paint, as a self-taught artist, in order to better converse with theartist (in fact we can imagine that his decision was also induced by a desire to pursue an autonomous research that in some ways diverged from Segantini’s, particularly on how a work should express the symbol: one could say, surely trivializing, that for Grubicy the idea had to prevail while for Segantini nature was more important, but the reading is a little more complex and this is demonstrated by Conti’s own interpretation of Segantini’s mountains). And then, the Grubicy-Segantini relationship is deepened with the paintings of the Brianza period: Segantini had moved to Brianza as early as 1880 and would remain there until 1886, when he moved to Savognin, in the Canton of Grisons. In between there is the beginning of the working relationship between the painter and Vittore and Alberto Grubicy (later, in 1890, the year of the breakup between the two brothers, Segantini would remain with Alberto but maintain cordial relations with Vittore), there is the first win of an international prize (in Amsterdam, in 1883), there is the first solo exhibition at the Permanente in Milan. And, above all, there is a new orientation in his investigations, which, if at the beginning of the Brianza period had not deviated one iota from the scapigliate research of the beginning (the rediscovered Ninetta del Verzéand, of uncertain date, probably painted between 1880 and 1883, is an example, but already a work like the Kiss at the Cross, a little later, shows a’aptitude for probing the potential of light that is completely new and already marked by an unprecedented sensibility), beginning in the mid-1980s they began to deal with international painting, always at the urging of Vittore Grubicy who had become a sort of mentor for Segantini, able to bring him up to date on everything that was happening outside Italy. One of the merits of the Bassano exhibition is that it brought together in the rooms of the Museo Civico a number of paintings by international artists with whom Segantini measured himself, or who, without any awareness, shared elements of his research. An early moment of confrontation was with the painters of the Hague school, and it led Segantini on the one hand to soothe his palette and on the other to concentrate on pastoral themes: it clears the air in this regard to compare Segantini’s very dense if late Propaganda (it was from 1897, was drawn for an album of socialist themes, but confronted with the sowing theme long frequented by Dutch painters: after all, the etymology of “propaganda” refers precisely to work in the fields), Matthijs Maris’s Sower , Vincent van Gogh’s (yes, Bassano audiences will also be able to see a drawing by Van Gogh, an element to be emphasized given the difficulty of seeing his work in an exhibition where he is not the main actor) and Jean-François Millet’s. And without Millet, who is also present in the exhibition with a Shepherdess with her Flock lent by the Musée d’Orsay, one could not explain the Segantini who stands between the early and the Divisionist phase, the Segantini capable of producing works appreciated even by his contemporaries, such as the Return from the Pasture or the fundamental L’Averse (also known as After the Storm), a canvas, the latter, of close investigation of the real, but also a poetically inspired work, in which the contrast between the large piles passing over the shepherdess and her sheep and the glare of the sun on the horizon anticipates the Symbolist outcomes of the mature Segantini. The comparison with Millet is one of the exhibition’s key junctures, despite the fact that the Arcense painter made no mention of it in the autobiographical material he was to produce after he met with success (material that should be taken with all due caution, since Segantini recounted his past not to give a truthful image of himself, but to construct for himself a very personal mythography): However, some of his contemporaries had already noticed this dialogue, which took place mainly through black-and-white photographs, and which is central to understanding, writes Servane Dargnies-De Vitry in the catalog, in a contribution entirely devoted to exploring the relationship between the two artists, how Segantini had come to conceive “a symbolism that tends neither to abstraction nor to an ethereal idealization” but which is grounded, Julius Meier-Graefe had already noted, “on rough Alpine concreteness,” on the observation of the real as a “gateway to the spiritual.”

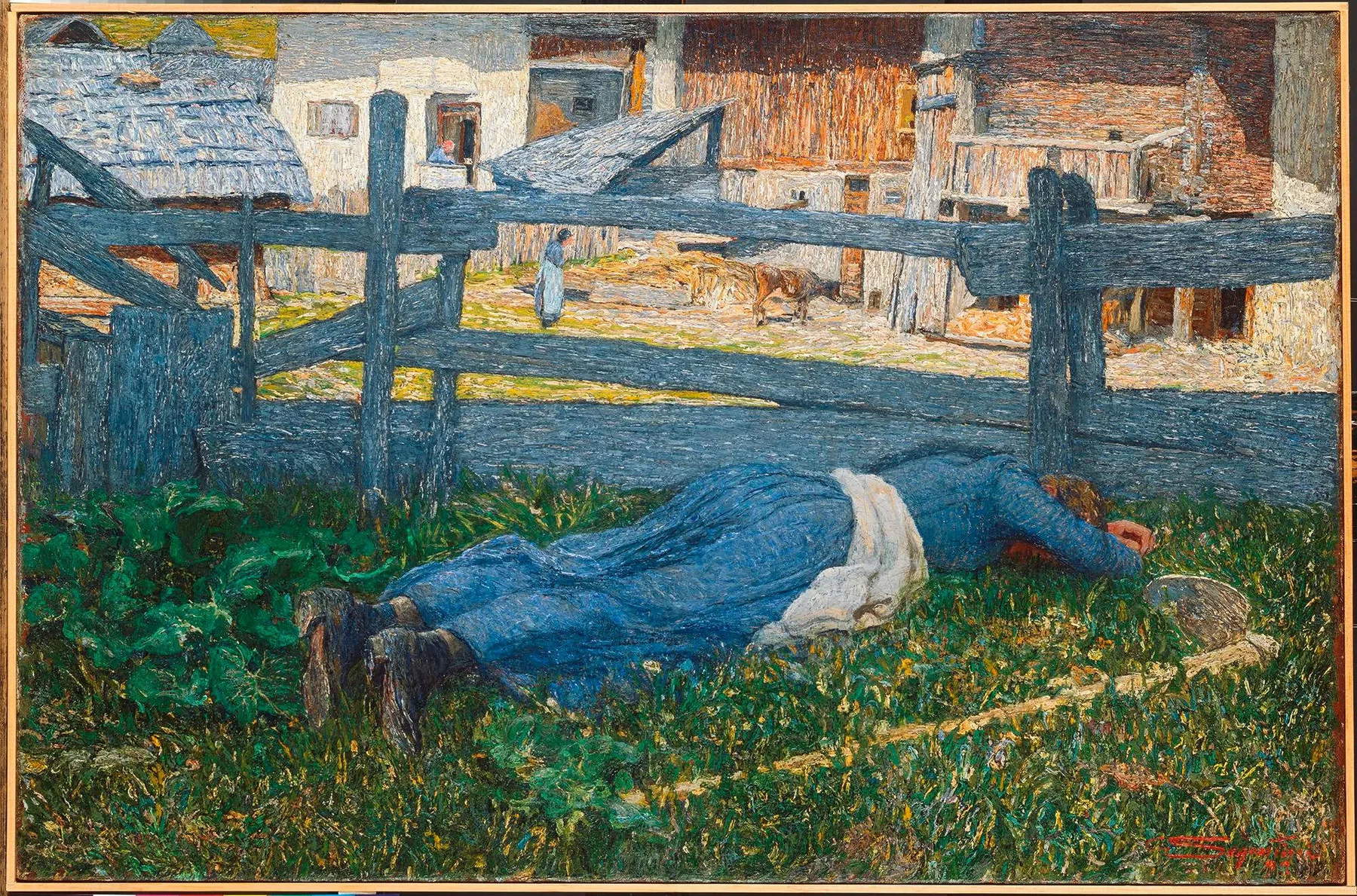

The first, highest outcome of this paradigm is precisely theHail Mary at Transept, which in the exhibition is reread not already as Segantini’s first pointillist work (as has often been done in the past), but as a fundamental transitional work, not least because it was painted in two versions, one from 1882 and one from 1886, moreover in several phases, and while Vittore Grubicy had begun to delve into the theory of color that was fascinating the French painters, above all Georges Seurat and Paul Signac, the founders of pointillisme, to whom Grubicy himself looked with extreme interest, so much so that he suggested to Segantini yet another transformation of his painting. We no longer have the first version, but the second, executed when Segantini had already moved to Savognin (and then repainted almost completely at a later time, as the technical investigations carried out for the exhibition confirmed), is a painting that begins to confront the ideas that were coming from France, although the “pointillism” that the painter would have developed in Graubünden, and which is to be understood as the use of touches of color, of tiny patches of pure pigment (i.e., not mixed on the palette) juxtaposed in order to give the relative the effect of the color that is created as a sum of lights by observing the painting from a distance, is here limited to a few elements (the sun on the horizon, some veiling on the sheep): the importance of theHail Mary in transborder should be considered, of course without taking into account the symbolic bearing of the painting that contributed to Segantini’s success and the evocativeness of an image that is carved in the mind of those who see it (it is perhaps Segantini’s most memorable painting), because of its character as a painting of passage, which with “the rendering of the light of the sky [...] and the decomposition of it on the water and on the curved timbers of the boat, and also the subtle colored brushstrokes [...] of the shore” stands as “a first yet timid step toward a fuller understanding of the neo-impressionist or more properly divisionist optical instances” (so in the catalog Anna Galli, Simone Caglio and Gianluca Poldi).

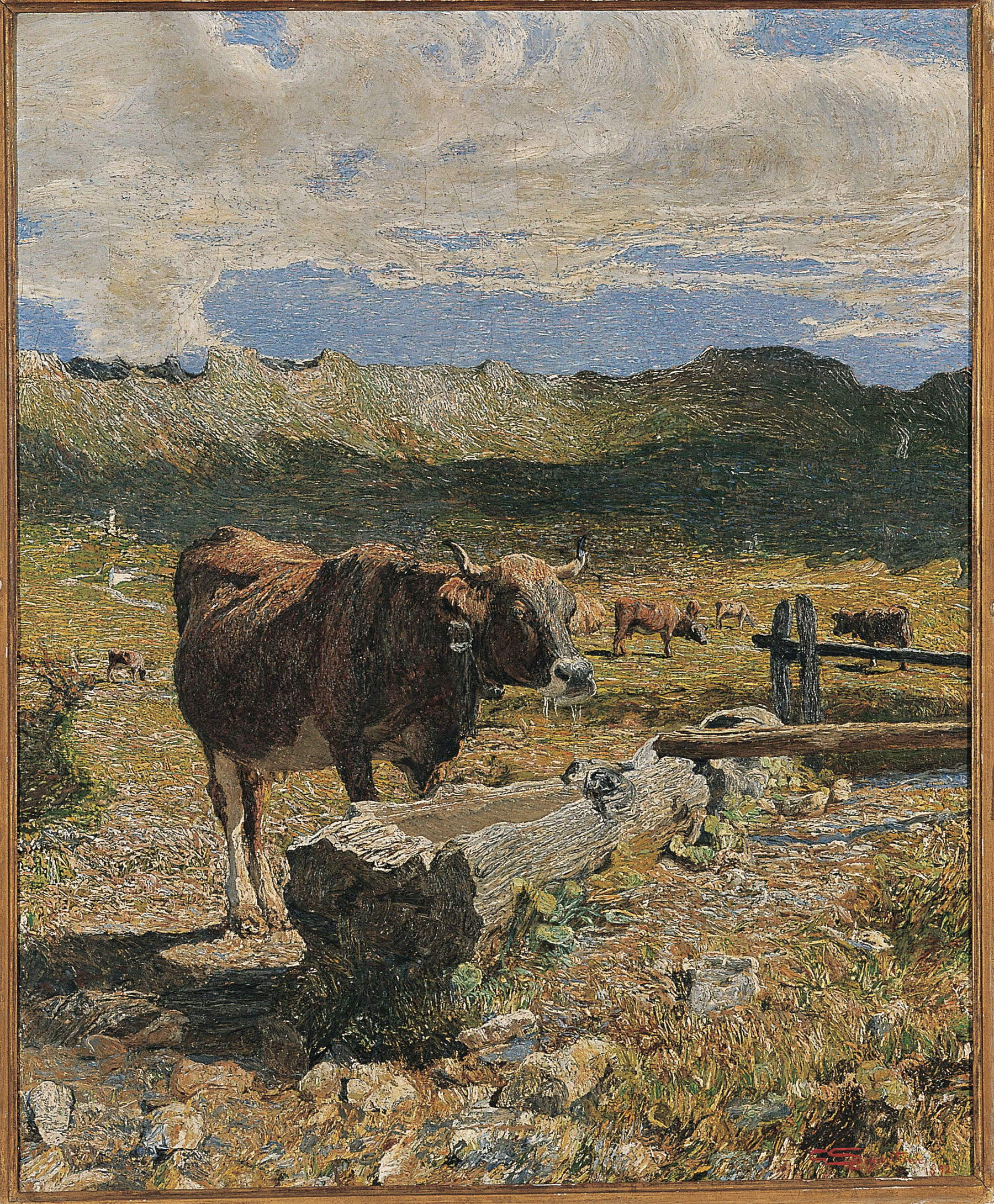

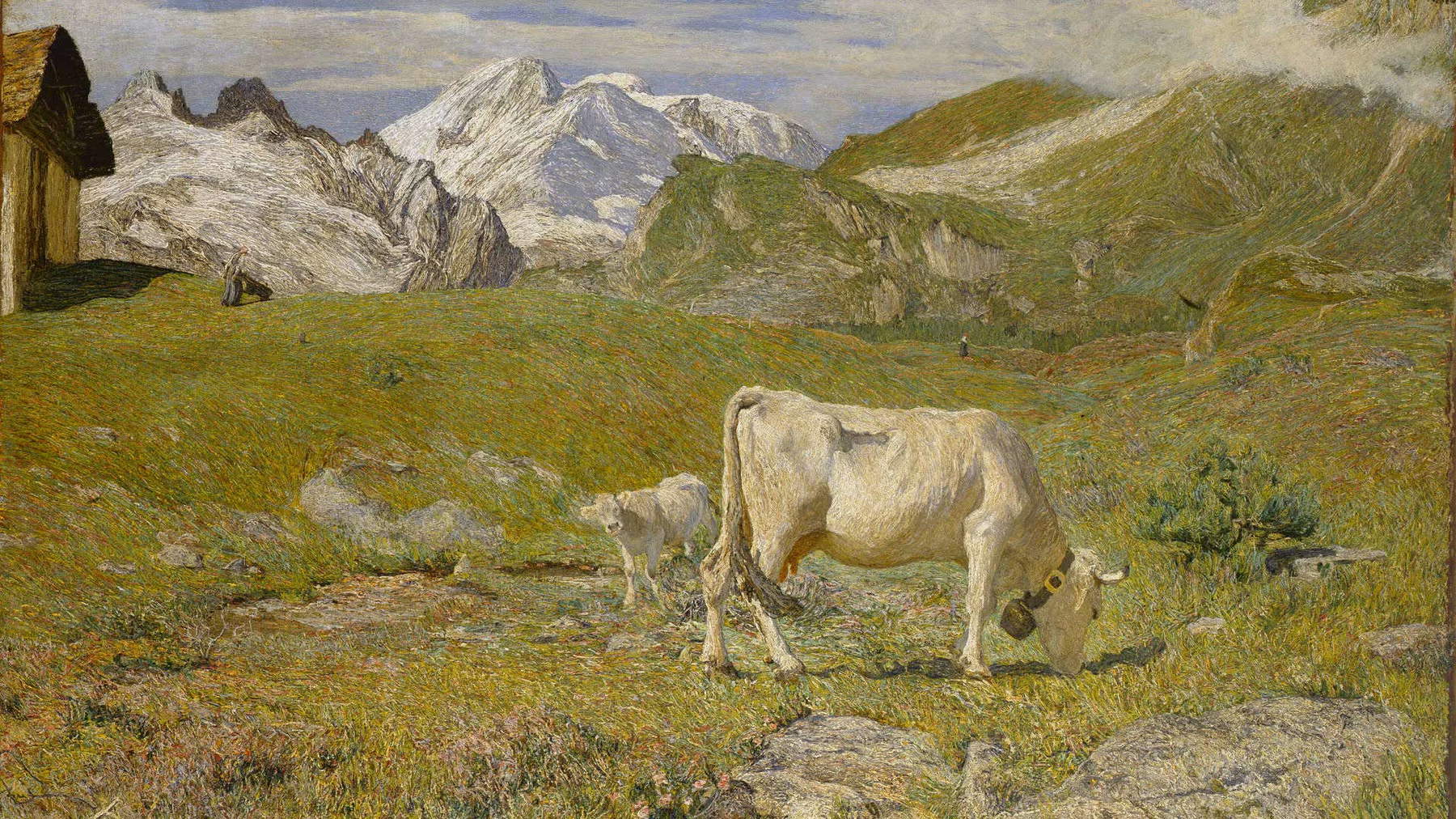

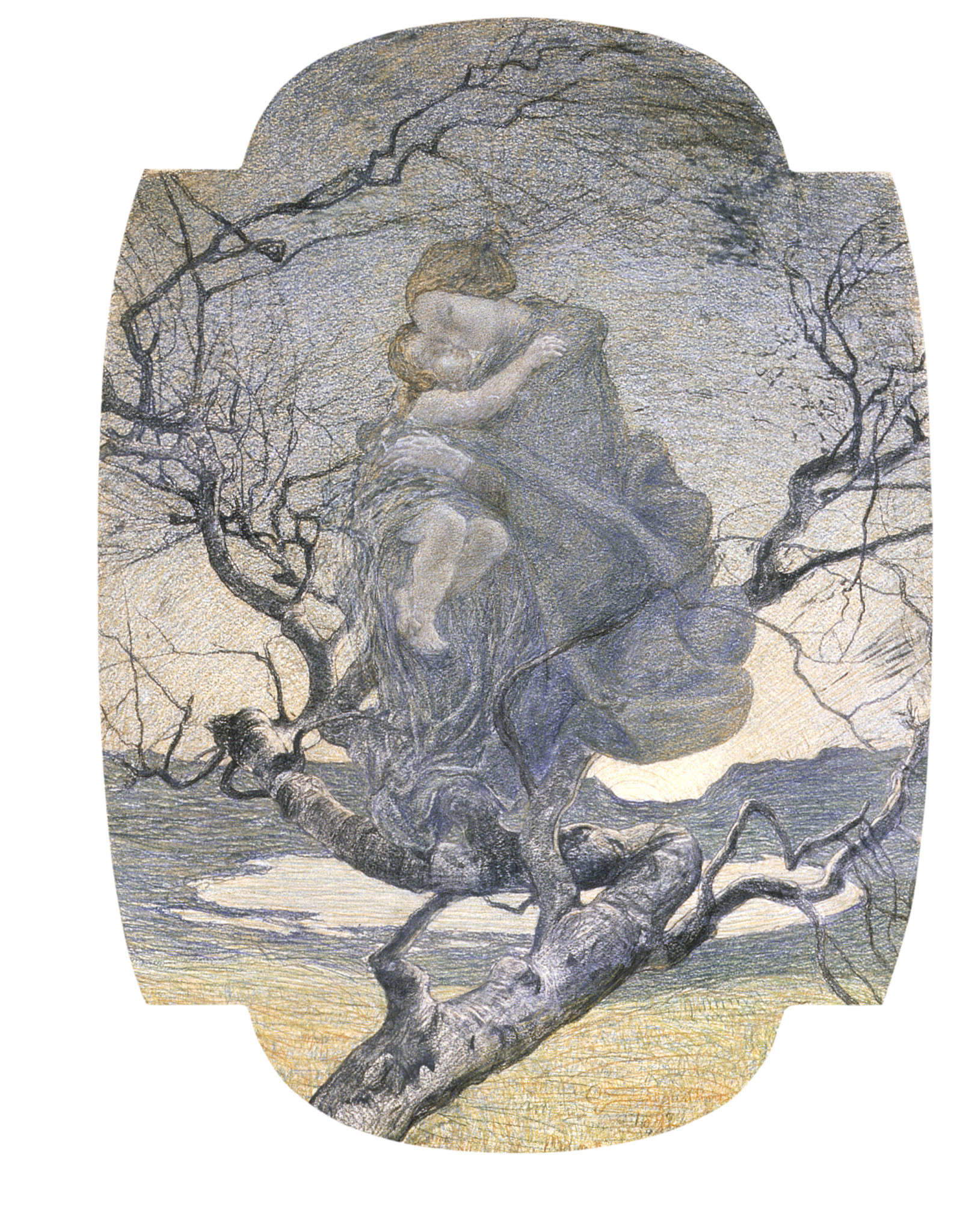

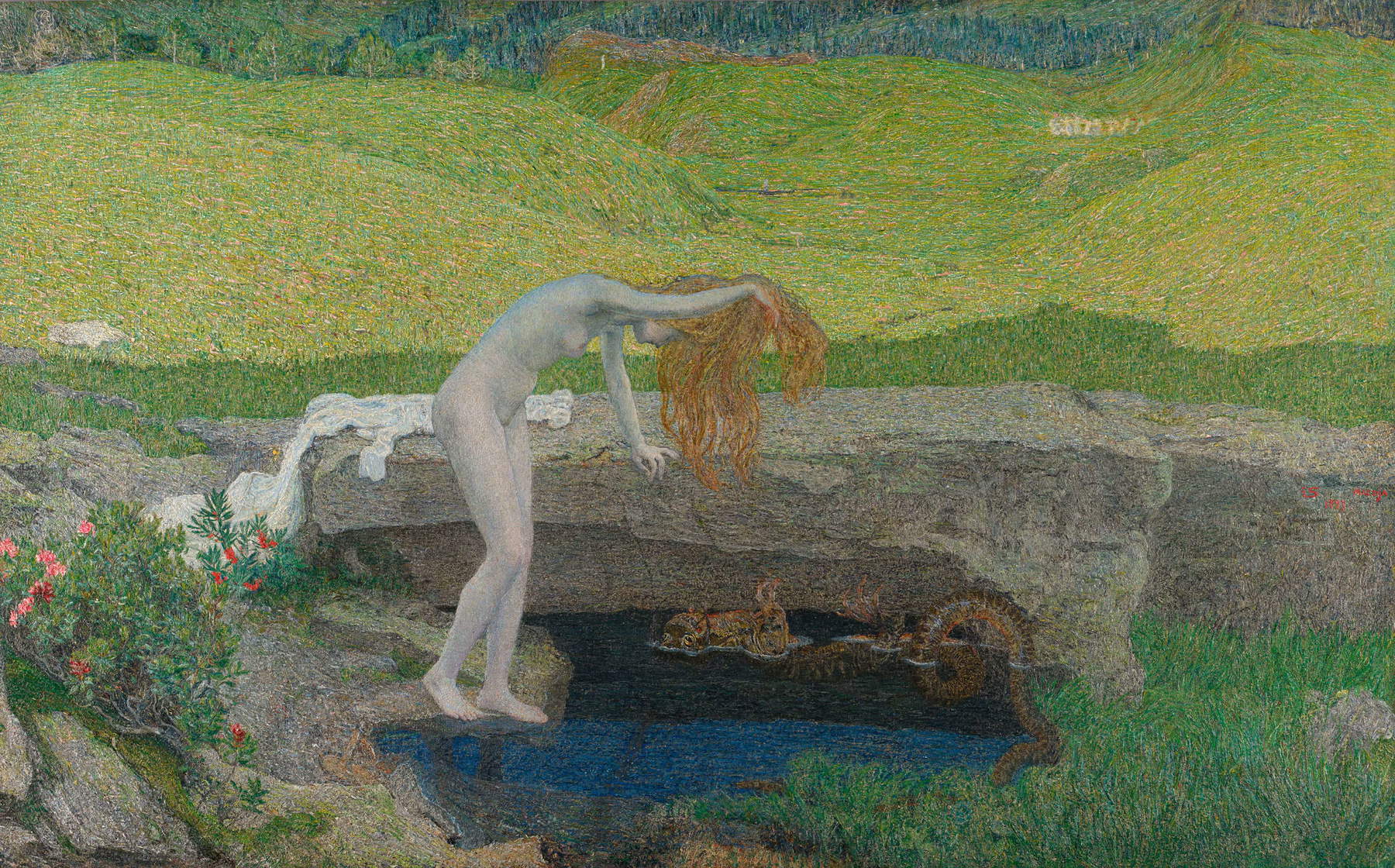

A more accomplished Divisionist experimentation would begin later, and one of the first outcomes of this new investigation is the aforementioned Autumn Sun, another central work in Segantini’s career, a work that marks the beginning of the most intense phase of his activity, immediately after theHail Mary in Transshipment: it is from this painting, a painting in which the brushstrokes begin to become mellower and longer and the study of light more attentive to rendering the chromatic variety of the gleams that refract on objects, that Segantini begins a more marked path of defining his pointillism that would later culminate in works such as the 1888 Contrasto di luce , which the painter himself pointed to as an example of his quest (“If modern art will have a character, it will be that of the search for light in color,” he wrote at the end of 1887 referring to this very painting), theAlpe di maggio, a study of twilight in the guise of a placid high mountain pastoral scene, the Brown Cow at thewatering trough that celebrates the poetry of nature, or as in radical works such as the Rest in the Shade, theSad Hour and the Return from the Woods in which the first signs of the Symbolist afflatus that would characterize Segantini’s later work can be felt. Already reading these works, Domenico Tumiati, who wrote about them between 1897 and 1898, went so far as to say that in Segantini’s works there is “enclosed a Nirvana: the spirit seems to fall asleep in the bosom of things.” It is on the basis of the harmonious agreement between technique and idea that the exhibition suggests interpreting Segantini’s last years: the Trentino painter’s vision, already beginning with the melancholy mountain scenes of theOra mesta and the Ritorno dal bosco, moves between nature and symbol, finding that personal path that would make him a central artist for European symbolism. Even when he was painting nature, be it the aforementioned Brown Cow at the Trough and other works that the visitor encounters as he heads toward the conclusion of the exhibition (the Spring Pastures, for example, or the Stone Pine Branch), Segantini had in mind a sacred, transfigured, ethereal idea of the landscape, and he would declare it himself, who in the meantime had become an avid reader: he was no longer the ungrammatical mountaineer who wrote letters full of jibes to Grubicy, but was now an up-to-date artist who was aware of what he was doing. The purpose of continual study, Segantini wrote in a letter to his writer friend Anna Maria Zuccari Radius, who signed his novels as Neera, is to take possession “absolutely, frankly of all Nature, in all gradations, from sunrise to sunset, from sunset to sunrise, with the relative structure and form of all things; in order to create then energetically, divinely the work that will be all ideal.” Segantini had matured a grandiose, spiritual, pantheistic idea of nature, often supported by visionary and openly allegorical works (in the exhibition one can admire, for example, theAngel of Life and Vanity, which nevertheless do not deviate from the technique that Segantini had begun to develop with his works ten years earlier), and which isexpressed by means of a painting that, with its chromatic variations, with its attempt to capture light and its infinite flashes, must not limit itself to reproducing reality, but must be able to make idea and nature coexist, one the mirror of the other. In this vision, moreover deeply conscious, resides all the originality, all the novelty of Segantini’s painting.

The exhibition, it has been said, does not forget the international dimension of Segantini’s art, which is contextualized not only through the continuous comparison with his contemporaries, but also by means of constant references to the successes that punctuated his entire career as an artist, successes that came in part thanks to the effective, lasting promotion of the Grubicy brothers, notably Vittore: exhibitions in Venice, in London, at the 1889 Universal Exhibition in Paris, at the Salon des Vingts in Belgium, participation with no fewer than 29 works in the inaugural exhibition of the Vienna Secession in 1898 (where he was admired by many Austrian painters who considered him among their points of reference, among whom it is possible to include Gustav Klimt: Segantini’s relationship with Austrian artists is adequately investigated in the catalog in Alessandra Tiddia’s essay), sending works to Zurich, Germany, the United States, even Guatemala, and then the project for a huge Panorama of the Engadine for the Swiss Pavilion at theParis Expo of 1900 (later unrealized due to lack of financial resources), a deluge of critical articles, mostly favorable, which were often divided on the reading of his works, on the meaning that should be attributed to his visions (Francesco Parisi’s contribution in the catalog is revealing in this sense). When Segantini died on the Schafberg in 1899 he was probably the most famous Italian artist in the world, and one of the most important and recognized artists in Europe.

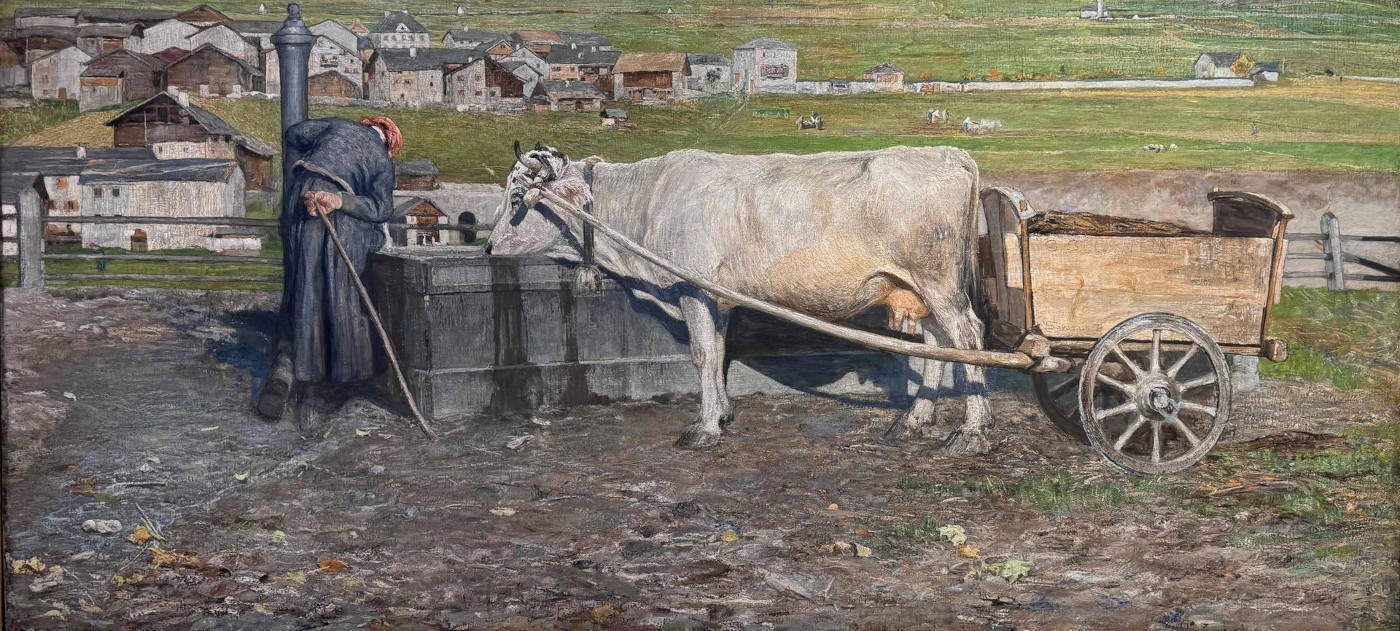

One of Segantini’s most notable successes was also the sale, in 1892, of his masterpiece Alla stanga to the State, for the National Gallery in Rome, sold for the sum of 18 thousand liras, against the initial 25 thousand. A very considerable sum: we are talking, roughly, about a final transaction worth 87 thousand euros today (it would have been Vittore Grubicy who convinced the painter to give up part of the profit in order to see one of his works enter the main national museum of contemporary art, and Segantini would never have forgiven him, because he felt as if his friend had taken money out of his pocket: other than a naive painter!). In the same year, Segantini had taken part in an exhibition in Turin where one of his paintings, thePloughing which is now in the Neue Pinakothek in Munich, raised the perplexity of Umberto I, who, according to an anecdote reported in the literature and evoked by Niccolò D’Agati, reportedly expressed some perplexity in the presence of the work: he did not understand why Segantini had done the blue horses. And he had preferred to him the landscapes of the older Carlo Follini, a talented artist though more tied to a rather mild realism. As luck would have it, there was someone at the Ministry of Education, which was responsible for purchases for the national museums, with a vision a little sharper than the king’s.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.