Puffy, full, fake, soft, touchable clouds. Folds that look like wet metal. Ivory faces, slightly flushed, delicate, expressive. He is the easily recognizable artist Malosso, and it is probably also to this recognizability that we owe the success that befell him in the Cremona of the second half of the sixteenth century. A rumor that Carlo Cesare Malvasia reports in his Felsina Pittrice has it that Giovanni Battista Trotti was nicknamed “the Malosso” by Agostino Carracci, at the time when the Cremonese had moved to Parma on the back of his success: “Avendo egli per concorrente in Parma il tanto più di lui favorito e stimato Cavalier Malosso, solea direa aver egli dato in un mal’osso da rodere.” Translated in today’s expressions, Carracci would have said that Trotti had given him a hard time. Reality, admittedly, is less suggestive than myth, since there appear to be attestations of the nickname “de’ Malossi” carried by the Trotti family for several generations. And we do not know for what reasons. The anecdote, therefore, is likely a figment of the imagination: the fact remains, however, that the legend of Malosso was still alive in the late seventeenth century, more than sixty years after its demise. Today, on the other hand, that of Giovanni Battista Trotti is, it would be said, a name known only to specialists or a few enthusiasts, and it is not difficult to understand the reasons for an oblivion that clashes strongly with the supreme fortune that Malosso had during his lifetime: Trotti remained a painter of local scope, most of his production being squeezed between Cremona, Parma and Piacenza (although his paintings also reached other centers: Milan, Pavia, Brescia, and a long sequence of smaller towns), and above all, his production came at a historical time of strong changes in taste, which already on the early of the seventeenth century would reward the Carracci’s path of the natural, not to mention the Caravaggism that would soon spread to the Po Valley plane as well, as well as, above all, the Emilian classicism that would supplant in the turn of a generation the whirling virtuosity of the Malossians. Emilia of the early seventeenth century already spoke a language that was the exact opposite of the one Trotti had wanted to impose on his patrons, and succeeded.

Those who wanted to know the reasons for his success should think, precisely, of the patrons. He was Malosso’s “rigorous interpreter of the dictates of the Counter-Reformation,” capable of a “fidelity that made him a particularly sought-after painter on the local art scene, at a time when religious instances played a preponderant role.” this is how Antonio Iommelli, director of the Civic Museums of Palazzo Farnese in Piacenza, which, together with the Diocesan Museum of Cremona, are devoting a small but dense exhibition to Trotti this year(Il Cavalier Malosso. Un artista cremonese alla corte dei Farnese), curated by Iommelli himself for the Piacenza venue and by Stefano Macconi and Raffaella Poltronieri for both. A painter not only capable, then, of making himself a dutiful exegete of what the patrons wanted, but also of weaving relationships fundamental to the development of his career (with clients, yes, but also with artists and men of letters: he was in relationships with Federico Zuccari and Giovan Battista Marino, among others, and he married Laura Locatelli who was the niece of Bernardino Campi, his master as well as one of the most highly regarded painters of sixteenth-century Cremona), he was commercially savvy, he was a versatile artist capable of designing sumptuous altarpieces’altarpieces as well as paintings for more everyday devotion, ephemeral apparatuses for the Farnese court and architectural and furniture designs, aided by an efficient, productive, well-organized workshop.

It must be given credit to the curators that it is not easy to put together an exhibition on Malosso. To gather together all the most significant things of his production would require large spaces and large resources, since almost all his most relevant works are anchors of considerable size, most of them still firmly attached to the altars for which they were conceived: therein also lies the fascination of this artist, and it is one of the beneficial effects of the substantial disinterest that posterity has manifested in his art, if anything at all. Therefore, a large exhibition is not to be imagined: few works have made their way to Cremona and Piacenza, however, that little allows one to get a rather precise idea of what Malosso’s art was. One could consider this exhibition a kind of introduction. And, at the same time, a rediscovery, since Giovanni Battista Trotti has been set aside even by contemporary critics. And then perhaps the double review on the border between two regions could be, perhaps, a viaticum for new illuminations.

Wanting to follow as natural an itinerary as possible, one might suggest starting the visit from the section set up in the Diocesan Museum of Cremona, since it is here that thehumus on which Malosso’s art sprouted is investigated, albeit in brief. He was trained in the workshop of Bernardino Campi, who would later become his father-in-law, as mentioned above: the opening of the exhibition presents the two artists side by side, juxtaposed in a genre, that of portraiture, which one would not immediately associate with Malosso, yet the Cremonese artist, even in this strand of his career, less beaten than in others, was able to produce extremely interesting results. The quality of his portraits does not reach that of his master (Campi’s Portrait of a Gentleman with Dog , a work in a private collection, is an elegant, very fine portrait, almost of Moroni’s brand, were it not for the fact that this work, compared to Moroni’s portraits, appears more algid and restrained): Malosso’s are more material, thicker, and more schematic, and the comparison with a successful, professional portraitist such as Bernardino Campi cannot but speak in the latter’s favor. Malosso’s portraits, however, also allow themselves to be appreciated: the concentration of the apothecary (perhaps, Raffaella Poltronieri speculates, it is Siface Anguissola, Sofonisba’s cousin: it is also an interesting work for probing Malosso’s relations in the Cremonese milieu of the 1680s, when the artist was in his early twenties) and the stern expression of the Augustinian (perhaps Teodosio Burla), the latter probably Malosso’s best portrait, suggest that he, too, had some familiarity with the genre, although one would be hard pressed to consider him a portraitist.

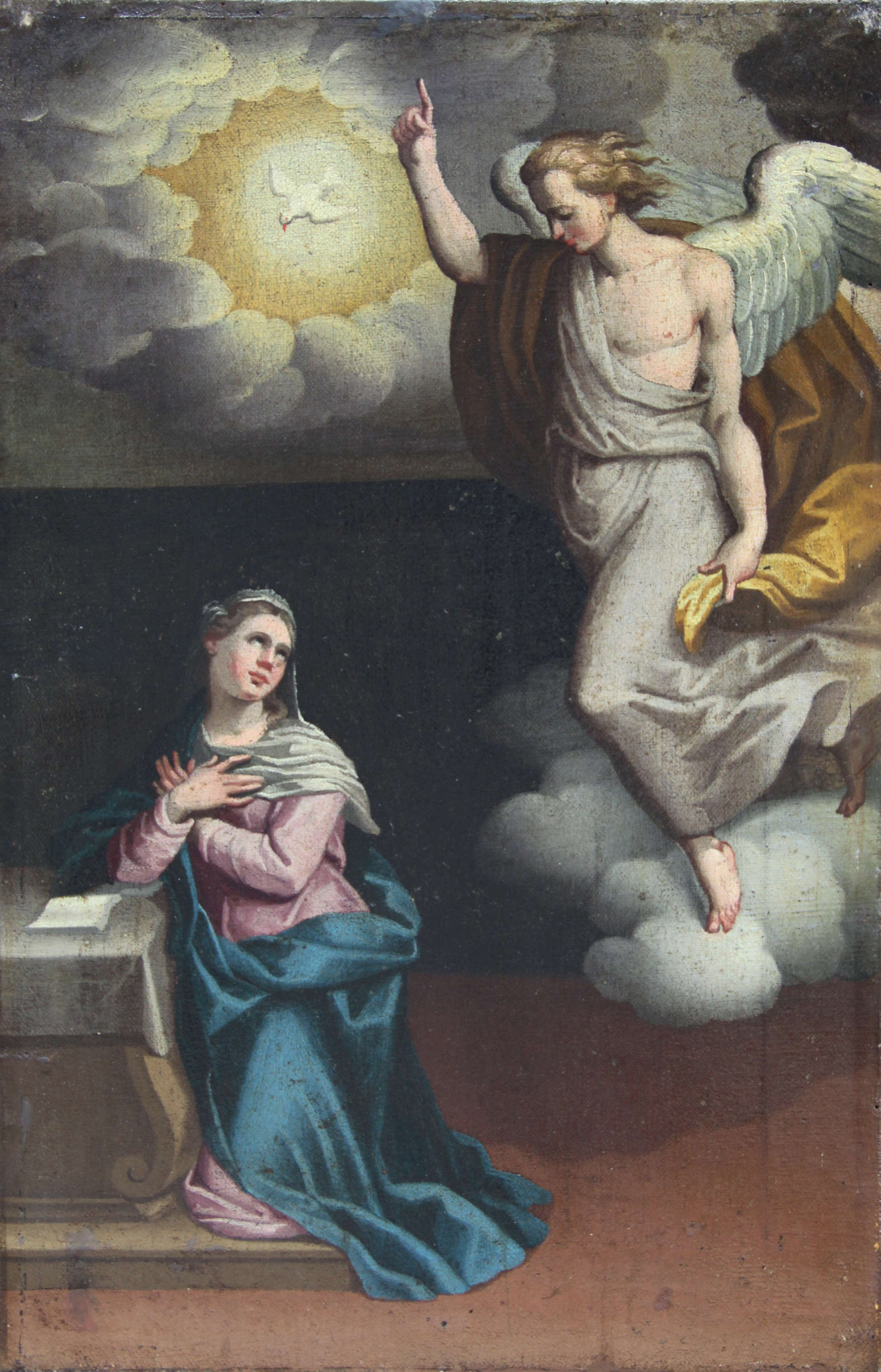

Malosso’s best things were to come in the sphere of sacred production, where from the very beginning, Adolfo Venturi also acknowledged to him almost a hundred years ago, “he took a path opposite to that of his cold and quiet master, seeking from the beginning spectacular effects, tumult of compositional lines, emphasis of gestures.” The comparison with Antonio Campi (who was not related to Bernardino but was nonetheless one of the most important artists of mid-sixteenth-century Cremona), present in the exhibition with a Sacra famiglia con santa Lucia never before exhibited (it is a kind of intermediate study for the counterpart altarpiece now at the Ringling Museum in Sarasota, Florida), shows that Malosso sought an original way from the outset, tried to set an alternative to the compassed manner of his masters, his references: this can be seen in the panels with the Mysteries of the Rosary that in ancient times accompanied a Madonna of the Rosary painted by a 30-year-old Malosso for the church of Santi Giovanni Battista e Biagio in Romanengo (the panels on display in the exhibition are works executed with wide concurrence of the workshop, but the Malosso approach is clear and is particularly noticeable in theAnnunciation, the most interesting of the panels on display, which already contains the salient features of the painter’s figure), but it is especially seen with the most important of the works exhibited at the Diocesan Museum, the Virgin in Glory interceding for warrior Cremona with Saints Omobono and Imerio, a work from the Ala Ponzone Museum in Cremona in which the city is depicted with the attributes of the goddess Minerva as she is presented to the Madonna by the two patron saints. Here they are, then, those salient features: the fluffy clouds that one almost seems to be able to feel, the metallic folds, the swirling composition, the iridescence, in the figures the delicacies of Correggio’s brand, the landscape passages of Nordic taste, the glazed, muted, light chromatic range. Evident are the references on which Malosso must have meditated: Bernardino Gatti and Camillo Boccaccino seem to be the most immediate precedents, although reworked to smooth out the more extreme points in order to meet the tastes of a large clientele that demanded images that were not too complex, and animated by a dramatic force that would be evident especially in the late phase of his career, a force already capable of projecting Cremonese painting into the new century. What gives an account of this force is above all a sheet, displayed at the end of the itinerary together with the drawings of some of his colleagues to bring out affinities and divergences: the Lamentation over the Dead Christ from a private collection, a study for the altarpiece, now lost, that the artist painted for the oratory of Santa Maria Segreta in Cremona in 1601: the drawing allows us to appreciate not only the vigor of the emotional tension that the artist on the end of his career was able to imprint on his compositions, but also the originality of the inventions of ’a painter who, also by virtue of these outcomes, can be defined, in the words of curator Stefano Macconi, as the only Cremonese artist “capable of developing a language independent of the mere resumption of Campesque models.”

At the Civic Museums of Palazzo Farnese, the exhibition offers an opportunity to appreciate the reunion of the three pieces that make up the Salazar Triptych, namely theAdoration of the Shepherds signed and dated 1595, which belonged to the Bank of Piacenza, and the two side compartments with St. Sebastian and St. Diego d’Alcalà, which recently resurfaced on the antiques market and were purchased by a private Dutch collector. To make this result possible, it should be noted, was an important work of coordination between the public and private sectors, since the merit of having identified the current owners of the two side panels must be given to the association of the Friends of Art of Piacenza, whose push was decisive in allowing the reunion of a triptych with an important history, which was divided during the 20th century. Malosso had painted the work for the Capuchin church in Regona, a village near Pizzighettone, four years after moving to Piacenza, which dates back to 1591. This was the most successful period of his career: suffice it to show his success by the name of the patron who commissioned him to paint the Regona triptych, Don Diego Salazar, a Spanish diplomat who at the time held the position of Grand Chancellor of the State of Milan. Salazar had several estates in the Pizzighettone area and, to show his munificence and devotion, a few years earlier, in 1584, he had promoted the foundation of a convent on the road that joined Regona to Pizzighettone. To crown the project, he asked Malosso for a triptych to be placed on the altar of the church in which Don Diego planned to have his heart preserved. The painting is mentioned in Salazar’s 1600 will, where the “speciosa tabula quae nativitatem refert Domini Nostri Jesu Christi,” or the beautiful panel depicting the nativity of Jesus Christ, is mentioned. In the nineteenth century, attempts were also made to identify the effigy of Diego de Salazar and his wife Francesca de Villelè in the two figures appearing on the left in the central panel, two shepherds in an ecstatic attitude, especially on account of the noble coat of arms with the thirteen stars painted by Malosso on the shepherd’s flask. However, because of the way the figures are posed, should one attempt to identify the patron and his wife among the characters depicted, it is more likely that they should be identified with the two figures kneeling in the center of the scene, a much more fitting attitude for two donors who wished to be effigyed in the altarpiece.

The work would have known a certain fortune (at least two copies of theAdoration of the Shepherds are known, one kept at the Palazzo Comunale in Caravaggio, the other in the office of the General Director of the Hospital of Crema, but coming from the church of Santa Croce in Soresina), and between the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries there are several local scholars who speak of it. Then, for some reason, nothing more was heard of the Salazar Triptych for quite some time, until 1957, when Piacenza art historian Ferdinando Arisi reported the panels in the collection of the Anguissola d’Altoè family of Piacenza, who would inherit them at an unspecified time. By 1974, however, the central compartment had changed ownership, and one can probably place around this date, or shortly before, the dismemberment of the Malossian machine: an unusual fact, moreover, that a triptych was separated so recently. In 1992 theAdoration became part of the collection of the Banca di Piacenza, while of the two side panels nothing more was heard until 2023, when they were sold in an auction at Cambi’s in Genoa, where they were listed as a work of the “19th-century Cremonese School,” with a very low estimate, moreover (5-6.000 euros the pair), although the sale later quintupled the maximum estimate: the pair of paintings in fact fetched 30,100 euros, including royalties (evidently those who attended the auction realized that the two canvases were older than the auction house thought).

In the Salazar Triptych the compositional lesson of Bernardino Gatti returns, evident especially in the articulated structure and crowded composition, just as the Correggesque references are quite uncovered, especially in the expressions and attitudes of the characters, who are precisely delineated, almost as if each were a portrait: suffice it to see the Capuchin friar, perhaps a Saint Joseph in Franciscan garb, caught in the act of receiving a singular wheel of cheese from a young man depicted from behind, bare-chested, covered only by a red cloak, a white robe with lace inserts, and a white lynx fur coat. Figures with a strong visual and narrative impact, such as the child in the center holding two birds and with a basket of eggs and a lamb at his feet, offer the relative passages of everyday realism that recall the manner of Vincenzo Campi, while in the landscape in the distance, which is of the most interesting of Malossi’s production, the usual echoes of the north resound. There is also no lack of hints of vibrant realism, which the recent restoration of the work has helped to bring out: the pictorial rendering is enhanced by details such as the patches on the Franciscan habit, chromatically well-tuned, that restore a sense as of truth, of everydayness, of simplicity.

In the exhibition, the Salazar Triptych is displayed in the center of the Ducal Chapel, along with the fragments of frescoes, also by Malosso’s hand, that until the 1930s decorated the chapel that held the painting, at the culmination of a brief tour that opens with two sumptuous works by the Piacenza-born Malosso, both housed in Palazzo Farnese. The earliest, from 1599, is the Madonna and Child with Saints Anthony Abbot and John the Evangelist, executed for the church of Santa Maria delle Grazie: the scene, still steeped in Campesque suggestions, finds space within a classical architecture complete with Ionic columns and statues placed in niches, further crowding a composition that concedes nothing to emptiness, and where even the bare earth on which Saint John the Evangelist kneels is filled with finely investigated objects, including the cartouche on which Trotti adds his signature, looked at with some insistence by the pig of St. Anthony the Abbot whose snout peeks out from the right edge of the canvas, thus revealing that Malosso also had unsuspected animalier skills. And then, next, the challenging 1603 altarpiece with The Virgin and Christ Interceding for the City of Piacenza, formerly in the church of San Vincenzo. It is one of the Cremonese artist’s most interesting works as a canvas that, write Antonio Iommelli and Anna Perini, “stands as a point of connection and anticipation of the canons of Baroque art, particularly in the division of space on two levels”, namely that of the heavens, where the deities find their place, and that of the earth, for which a flap is reserved under the angels just enough to accommodate a distant view of the Piacenza skyline as itas it was at the beginning of the seventeenth century, with the clearly distinguishable profiles of Palazzo Farnese, the Cathedral, and the basilica of Santa Maria di Campagna, in a depiction that, Iommelli and Perini add, “stands out for its originality, in that it captures the profile of the city from an unusual perspective, that is, beyond the Po River, crowned by Mount Penice and animated by small figures and boats.” Closing the itinerary, an Apparition of the Virgin to St. Francis, a complicated work, with a Maloxesque layout but of lesser quality and open to other suggestions(primarily Ludovico Carracci), and therefore attributable to a pupil (probably Gian Giacomo Pasini known as the Nightingale, according to Raffaella Poltronieri), also offers the possibility of opening up on the artists who, to a certain extent, continued to reason on the lesson of Giovanni Battista Trotti.

The real exhibition, it would be said, opens outside the Diocesan Museum and Palazzo Farnese. The real exhibition of Malosso’s works is in the many churches for which he was called to paint, it is in the buildings of worship scattered throughout the two cities and scattered throughout the territory, it is on the altars from which his altarpieces never moved, it is in the silence of the great naves, it is in the dim light of the chapels, between the cities and the countryside, in Cremona as in Piacenza as in Parma, and then in Viadana, in Casalmaggiore, in Brusuglio, in Casalpusterlengo, in Bertonico, between Emilia and Lombardy and sometimes even beyond, where Malosso’s fame managed to reach. The double review that Cremona and Piacenza offer to the public must be seen above all as an invitation, because many of the best things about Giovanni Battista Trotti are outside museums: a visit to Cremona Cathedral to see the 1594Annunciation , one of his finest works, or the Resurrection of Christ in the Madonna del Popolo chapel, as well as the altar in the Blessed Sacrament chapel (for Malosso was also a talented interior designer , we would say today: it is an aspect of his production that the exhibition nevertheless does not investigate), and then at least at the temple of San Pietro al Po where one can admire the splendid Nativity and the Virgin and Child with Saints John the Baptist and Paul, also set within monumental classical architecture. Here, perhaps supporting material (a map, a flyer) would have been useful, to indicate to the visitor where in the area Malosso’s works can be found, and thus facilitate the enrichment of what the exhibition, a good exhibition, anticipates to anyone who follows it.

By arriving at the right times, however, in Cremona, the public will be able to follow the restoration of a painting from Malosso’s workshop live in the very rooms where the exhibition is set up. The effort to set up a dense itinerary was, moreover, commendable, despite the paucity of material available to the curators (between Cremona and Piacenza there are no more than a dozen works by Malosso, to which must be added the works of the artists summoned to build an adequate context: in all, the exhibition engages two rooms, one per venue), all accompanied by an excellent catalog, which prefers historical data over formal analysis, and constitutes a rich publication to learn about many aspects of Giovanni Battista Trotti’s art. Waiting, perhaps, for new opportunities to admire or understand those swirls averse to emptiness, those iridescent folds, those full vapors.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.