Before beginning to discuss the van Gogh exhibition in Vicenza, the new exhibition-entrepreneurial project of Marco Goldin and his Linea d’Ombra, a brief premise must be advanced: this time the starting point would not be, as with some of his other exhibitions, atrocious jumbles along the lines of the dreadful “Tutankhamun, Caravaggio, van Gogh,” nor would it be trumped-up thematic jumbles in the style of "the Impressionists and snow,“ nor would it be improbable and risky overviews of portraiture ”from Raphael to Picasso."

None of this: for the autumn exhibition at the Basilica Palladiana, Goldin was able to count on a decidedly substantial nucleus of drawings and paintings by Vincent van Gogh (Zundert, 1853 - Auvers-sur-Oise, 1890), most of which came from the Kröller-Müller Museum in Otterlo, Holland.

Of course, this is nothing particularly original or innovative, given the Kröller-Müller’s well-established and traditional habit of lending large portions of its van Gogh collection en bloc, and the situation in Vicenza is anything but unprecedented, since the first major exhibition on van Gogh held in Italy, the 1952 exhibition at the Palazzo Reale in Milan, also made extensive use of loans from the Dutch institution: However, it must be emphasized that the attribute “great,” on which much of the adjective that accompanies the exhibition in Vicenza seems to be based, means everything and nothing, and establishing who holds the record in “greatness,” whether the 1952 exhibition or the 2017 one, is a matter for futile combat de coqs, to be left willingly to those who love this kind of sterile dispute. In any case, re-proposing in 2017 an exhibition from sixty years ago (albeit with the ratio of paintings to drawings reversed: then there were more paintings than drawings; in Vicenza, on the other hand, the opposite happens), with all the necessary updates, would not be a deplorable operation in itself: only a couple of years back, the re-edition of Arte lombarda dai Visconti agli Sforza, curated by Mauro Natale and Serena Romano (who programmatically wanted to draw inspiration from the 1958 review of the same name by Roberto Longhi and Gian Alberto Dell’Acqua), was a meritorious operation, at least in our opinion. Therefore, this is not the problem.

|

| The entrance to the Basilica Palladiana in Vicenza for the van Gogh exhibition. |

|

| The entrance to the exhibition on van Gogh |

|

| The layouts of the exhibition on van Gogh |

With as many as one hundred and twenty-nine works, including paintings and drawings by van Gogh and by comparative artists (five works in all, by Jozef Israëls, Jean-François Millet, Jacob Maris, Anthon van Rappard, and Matthijs Maris), set up a straightforward and sensible project aimed at getting the visitor truly into van Gogh’s world, putting him or her in a position to understand the whys behind many of the works exhibited at the Basilica Palladiana, would have been, after all, not even too complex an operation, given also the fact that very few artists in the history of art are known as deeply as van Gogh. Of course, Goldin was not really being asked to delve too deeply into the specifics (he probably cared little about letting his audience know, for example, how reading Michelet had influenced the Borinage drawings, or how van Gogh’s approach to color had changed as a result of his 1884 exploration of Charles Blanc’s color theories), but at least to account for certain passages that the exhibition hints at, beginning with why Millet had been a constant reference throughout the Dutch artist’s entire career, or the technical and compositional choices of the Nuenen portraits, or the fundamental contribution that Adolphe Monticelli’s knowledge of art made to van Gogh’s painting in his Provence days.

Interestingly, one can encounter crucial junctures in van Gogh’s career in Vicenza: the 1880s drawings, the early experiments with oil conducted under Anton Mauve’s aegis, the aforementioned Nuenen portraits, some of the Paris works, the Cologne version of the Langlois Bridge, and much more. However, the problem is that, as usual, Goldin has decided to systematically kick all good critical intentions and throw it into the doggerel of the "soul,“ and if the clearly stated intention ”is not to isolate and comment in a cataloguing way on the major themes that emerge from the letters and works-which are also important for understanding the poetics and motivations of artistic choices-rather than to pose from a different perspective , that of the soul," then any reasoning that takes into account critical, philological, popular and didactic aspects of an exhibition necessarily becomes an idle argument. If the “themes that emerge from the letters and works” are secondary motives, if one believes that the only alternative to the ineffable throbs of the soul is a “cataloguing commentary,” if a concept as foggy as the “perspective of the soul” becomes the implant on which an entire exhibition project is held up, one might as well carefully avoid the panels penned by Goldin (who is eager to let us know that the exhibition’s narrative, minus the catalog cards by Teio Meedendorp brutally displayed on the walls of the exhibition layout, is his own work: each panel is in fact unfailingly signed with first and last name) and make an immersion in van Gogh’s painting without caring how many would like to suggest what feelings to have. This, of course, if one really feels the need to visit the exhibition (Vicenza, after all, is more convenient than Otterlo).

|

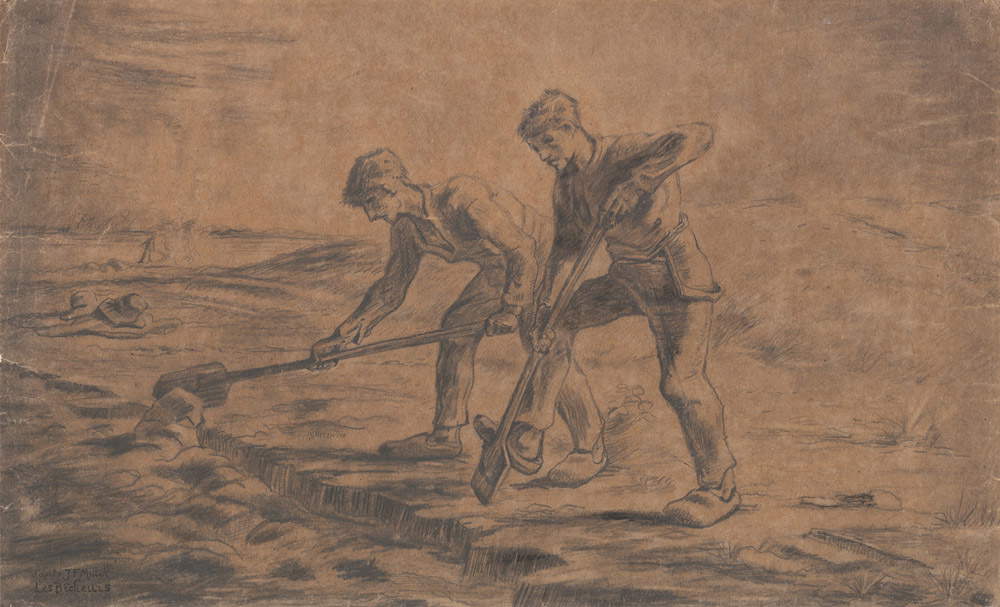

| Vincent van Gogh, Two Hoesmen, from Jean-François Millet (1880; pencil and black chalk on tissue paper, 37.5 x 61.5 cm; Otterlo, Kröller-Müller Museum) |

|

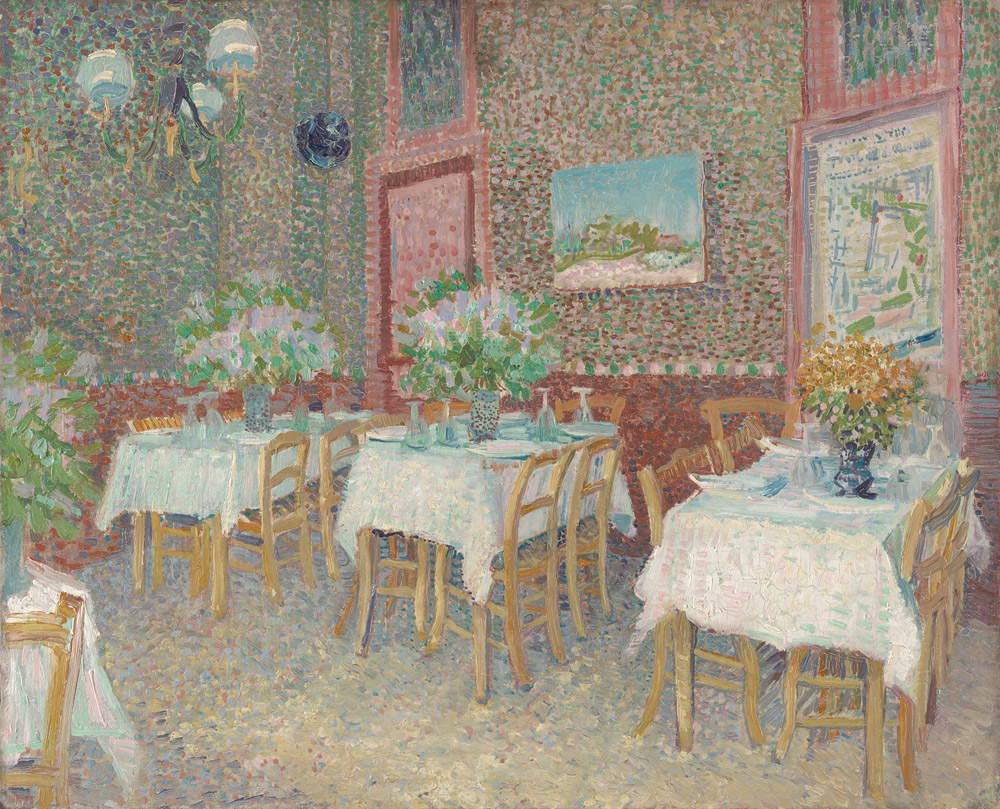

| Vincent van Gogh, Interior of a Restaurant (1887; oil on canvas, 45.5 x 56 cm; Otterlo, Kröller-Müller Museum) |

|

| Vincent van Gogh, The Langlois Bridge in Arles (1888; oil on canvas, 49.5 x 64.5 cm; Cologne, Wallraf-Richartz-Museum & Fondation Corboud) |

|

| Vincent van Gogh, Sheaf under a Cloudy Sky (1890; oil on canvas, 63.3 x 53 cm; Otterlo, Kröller-Müller Museum) |

The risk, otherwise, is meanwhile to get lost in Goldin’s swooning first-person narratives, amid “the dry, all-encrusted air of an emotion that overwhelms, shakes from within, settles in the depths of the heart.” the “swaying of the gaze and the breath” and the brushstrokes that become “real gems suspended in the clear air of Provence” (just to quote a few passages from the worksheets in the volume accompanying the exhibition, which, wisely, on the back cover is called a “book” and not a “catalog,” because to call it a “catalog” would have been an affront to real catalogs: only a few entries compiled, albeit without any bibliography-an absence that distinguishes the entire volume-by van Gogh scholars, such as the aforementioned Meedendorp or Cornelia Homburg) are saved. It is enough to be aware that such a product is the art-historical equivalent of a cinepanettone, and to be confronted with a van Gogh story conducted in such terms is a bit like imagining Onion in the guise of the protagonist of The Sky Above Berlin, just to give an idea. Or, to suggest even better the (very personal, it goes without saying) sense of annoyance felt by the writer (since it’s touching to talk about emotions), it’s a bit like listening to a Leonard Cohen record while your neighbor waits to mow his garden with the noisiest combustion lawnmower available on the market. And anyway, there is nothing wrong with that: it is enough to proceed cautiously with the terms, and avoid using high-sounding phrases such as “consecration of the vocation of the Basilica Palladiana as a place to experience art” to coat what is, to all intents and purposes, an entertainment product with a cultural patina that does not suit it.

And then there is the danger of having to see poor van Gogh reduced to the role of sad and derelict sidekick of the curator-actor: because Goldin did not just curate the exhibition and write the “book.” Nor has he limited himself to doing what he does best, which is to be theentrepreneur who with his well-rehearsed marketing of emotions has been able to create in two thousand people a day the need to go to Vicenza to sip his account of van Gogh’s “workshop of the soul.” No: Goldin is also the author of the panels arranged along the route, the creator and curator of the audio guide, the editor of an edition of van Gogh’s Letters obviously published by Linea d’Ombra, the playwright author of the theatrical monologue that inspired Matteo Massagrande’s paintings that occupy the penultimate room of the exhibition, and again the screenwriter, director, producer and narrator of the docu-film that is screened in the last room, set up like a ninety-seat cinema. Protagonism and ridicule are two concepts that are often very close. What’s more, Goldin is probably also the creator of the twenty-square-meter model reproducing the Saint-Paul-de-Mausole clinic, which the visitor is plunged into toward the end of the itinerary in the guise of a trashy shanty that comes to close the circle definitively around the “van Gogh in Vicenza” project. At the press preview, Goldin assured that he “took van Gogh on the side of the soul”: one wonders if he did not, if anything, mock him. Poor Vincent, after all, had already suffered far too much in life.

|

| The model of the Saint-Paul-de-Mausole clinic. |

|

| The cinema hall |

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.