In the late 19th century, Maud Cruttwell, author of one of the first extensive monographs on Luca Signorelli (Cortona, c. 1450 - 1523), wrote that the great artist from Cortona would be destined to find nothing but bitterness in Rome. Indeed, beyond the youthful exploits of the Sistine Chapel, fortune did not come to him in the city of the popes, even when he thought fate was on his side. The disappointment was bitter when, in 1513, Giovanni di Lorenzo de’ Medici ascended to the papal throne with the name of Leo X: Signorelli thought he would have an easy time getting commissions from the new pontiff, given that, years earlier, he had already worked for his household (think of the destroyed Education of Pan, executed in the late 1580s for Leo X’s father, Lorenzo the Magnificent, or the enigmatic and fundamental Medici Madonna, which can most likely be traced back to Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco’s commission). On the contrary, Signorelli had to return to Tuscany without getting any feedback, as also attested by a well-known letter that Michelangelo (Caprese, 1475 - Rome, 1564) sent in 1518 to the captain of Cortona, Zanobi di Lucantonio Albizi, to ask him to collect a debt that Signorelli owed him: “he told me that he had come to speak to the Pope,” Michelangelo writes, “[...] and that it seemed to him, chome dire?, not to be recongnized.” But if Rome was stingy with job satisfaction for Signorelli, the same cannot be said for what the city returned to him in cultural terms.

Retracing the traces of Luca Signorelli’s presence in Rome (this is the goal of the exhibition Luca Signorelli and Rome. Oblivion and Rediscovery, underway at the Capitoline Museums in Rome until January 12, 2020) means delving into the impression made on the Tuscan artist by the ancient vestiges, which were so fundamental to his art (and which the artist was able to see and study directly during his sojourns) as they were functional in forging the foundations of his painting, which Giorgio Vasari recalled was founded on “drawing and of the naked particularly” and on the “grace of the invention and arrangement of the instories.” drawing and grace with which, according to Vasari, Signorelli “opened to the majority of the artisans the way to the ultimate perfection of art, to which they were then able to give top those who followed.” If Signorelli was that “impetuous and tragic” artist (as Adolfo Venturi called him) whom we find in the Chapel of San Brizio at Orvieto Cathedral (whose paintings, according to Vasari, were “always supremely praised” by Michelangelo), if Pietro Scarpellini was right when he wrote that this great painter was able "to overcome scenographic assumptions with such ingenious solutions as to turn artifice into truth and oratory into poetry, and if he succeeded in maturing, as the curators of the Roman exhibition Federica Papi and Claudio Parisi Presicce write in the opening of the catalog, that “particular talent in the rendering in painting of nude figures, in foreshortening, in movement and well arranged in space,” the reference to antiquity becomes an inescapable topic.

The small Roman review (about a dozen works by Signorelli in all present) does not propose any particular novelty in the context of the topic “Signorelli in Rome”: new, however, is the intention to devote a small focus to the subject, not complete (by the curators’ own admission), but organically structured, and functional, on the one hand, to offer the public aninteresting popularizing opportunity around an artist now recognized (after centuries of oblivion: part of the exhibition focuses on this aspect as well) as one of the greatest of the Renaissance and as an artist without whom certain achievements reached by Michelangelo and Raphael could perhaps not be explained, and on the other to rekindle the spotlight on a subject on which there is probably still work to be done, since there are very few documents attesting to Signorelli’s presence in Rome, the extent of his stays and the terms of his activity in the city. It is also worth noting that the Capitoline exhibition is the third-ever exhibition on Signorelli, and follows the first monographic exhibition in 1953, held in Cortona and Florence (and unfortunate to have been hit by the extremely harsh controversy it unleashed among scholars: it took ten years for the aforementioned Scarpellini, with his 1964 monograph, to put things in order and draw a profile of Signorelli free of prejudice), and the other major exhibition event held in 2012 in Perugia, Orvieto and Città di Castello.

|

| A room in the exhibition Luca Signorelli and Rome. Oblivion and rediscovery |

|

| A room from the exhibition Luca Signorelli and Rome. Oblivion and rediscoveries |

|

| A room from the exhibition Luca Signorelli and Rome. Oblivion and Rediscoveries |

The exhibition opens with a twofold framing: first, the vicissitudes of Luca Signorelli’s effigy are presented to the public, offering an initial insight into the artist’s critical fortunes. The affair, although also proposed on the occasion of the 2012 exhibition and here enriched with the presence of the two nineteenth-century portraits of Signorelli, one executed by Pietro Pierantoni in 1816 and the other in 1848 by Pietro Tenerani, is quite singular: for centuries an erroneous portrait of Signorelli was handed down, namely the one that Vasari enclosed with the artist’s biography in his Lives, taking a resounding crab. The historian from Arezzo, in fact, circulated an image of Vitellozzo Vitelli, painted by Signorelli, mistaking it for that of the painter himself, moreover in a decidedly bizarre way, since Vasari claimed to have known Signorelli in person, albeit as a child: only in the late 19th century did we realize the blunder. Then, we move on to present the context of late 15th-century Rome, on the one hand through the image of the city in the plans of the time (as was the case two years ago for the exhibition on Pinturicchio and the Borgias, also held at the Capitoline Museums: the exhibition on Signorelli is structured on a similar layout and is in continuity), a topic to which an essay by Laura Petacco in the catalog is also devoted (this was an era of profound changes for a city that was shedding its role as a peripheral medieval center that had sprung up haphazardly amid the ruins of classical Rome and was transforming itself into the sumptuous capital of Catholicism), and on the other hand insisting in particular on the works of Pope Sixtus IV (born Francesco della Rovere; Pecorile, 1414 - Rome, 1484), who was pontiff from 1471 until his death and became the promoter of that intense renovatio Urbis of which, in this introduction to the review, the salient stages are retraced. Although strongly present in the political events of his time (seen in retrospect, the years of Sixtus IV were characterized by a pushed secularization of papal power), and however strongly criticized (the nepotism that characterized his pontificate reached extreme levels, and in 1476 the pope avocated to himself the appointment of the highest municipal offices, severely limiting the powers of the Comune), Sixtus IV actually gave a new face to the city: the jubilee of 1475 provided occasion for the modernization of many buildings and the erection of new ones (most notable were the construction of the Sixtus Bridge and the restoration of other bridges over the Tiber, including the Milvian Bridge and the Sant’Angelo Bridge, and again the arrangement of the road network, the building and renovation of hospitals and charitable institutions, starting with the restoration of the Hospital of Santo Spirito in Sassia to which, moreover, a room of the exhibition is dedicated, without calculating the impressive building reform that sanctioned further changes to the appearance of Rome). Among the most significant acts of Sixtus IV is also the donation of the ancient bronzes of the Lateran to the Roman people. Sanctioned on December 15, 1471, the donation took the form of a move contrived by the pontiff as part of the consensus-building around his figure that always distinguished his work, but in fact it represented at the same time the founding act of the Capitoline Museums, since the works were transferred to the Palazzo dei Conservatori on the Capitol, so that anyone could be given the faculty to observe them.

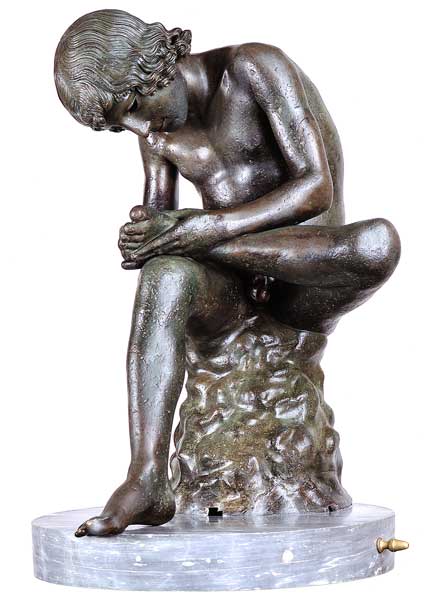

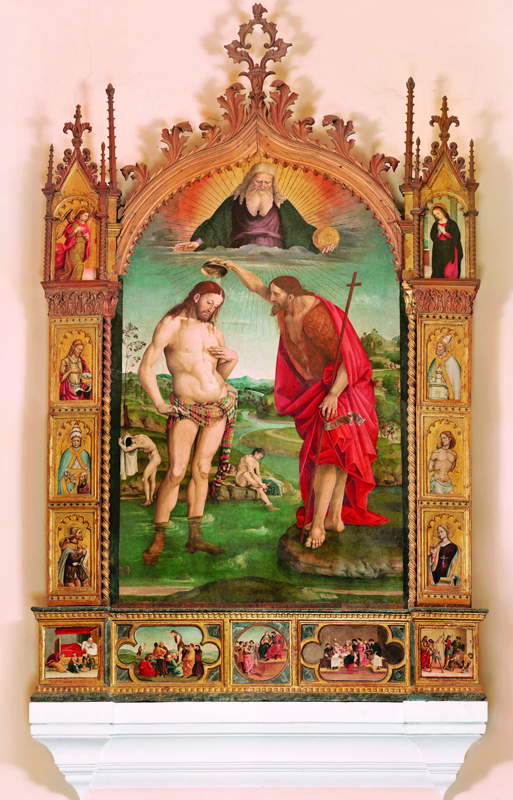

This is where the rest of the exhibition is grafted in. Also included in the donation was the Spinario, the bronze depicting a shepherd boy removing a thorn from his foot, very well known in the 15th century and even earlier, and which became the object of the attention of a vast plethora of artists by virtue of the originality of its pose (as is well known, it is seated, one leg on top of the other horizontally, and leaning forward to examine the thorn stuck in his left foot), as well as by effect of the grace and naturalness with which the child’s attitude is resolved. Signorelli, as anticipated, had been called to Rome, in 1482, for the frescoes in the Sistine Chapel, although initially his presence was not planned alongside those of Botticelli, Perugino, Cosimo Rosselli and Ghirlandaio. Signorelli later arrived, called along with the other Tuscan Bartolomeo della Gatta (Pietro di Antonio Dei; Florence, 1448 - Arezzo, 1502), to help as the work was delayed: thus, the Cortonese helped Perugino, together with Bartolomeo della Gatta, in the fresco of the Delivery of the Keys, also always together with his countryman he executed the scene of the Testament of Moses, and finally alone he completed the Combat over the body of Moses, later destroyed because of a collapse and replaced late in the sixteenth century by a homologous fresco by Hendrick van der Broeck. At this point, therefore, it is necessary to imagine Signorelli going up to the Palazzo dei Conservatori (and perhaps visiting some of the collections of antiquities that the more prominent Romans had taken to setting up in those days) and being fascinated by the sight of the ancient statues, and grasping important insights that we later find again, punctually, in his paintings. The first of these, among those on display in the exhibition, is the Madonna and Child arriving from the Alte Pinakothek in Munich: behind the two main figures we find a nude young man whose pose traces that of the Spinario. Moreover, the ancient statue is on display in the exhibition, in two versions: the bronze one from the Capitoline Museums and the marble Medici Spinario, now in the Uffizi. (The latter was probably already well known to Signorelli even before his move to Rome, since the presence of the statue in the Laurentian antiquities repertoire in the garden of San Marco is attested, and it is also known to have been known to artists of the early Florentine Renaissance: Giovanni Luca Delogu, in the file on the Bavarian Madonna compiled for the 2012 exhibition catalog, noted that the Medici Spinario “by Signorelli’s time constituted a well-established repertory image, having already been treated by Brunelleschi, Masaccio and Luca’s own master, Piero della Francesca, in the Arezzo cycle.”) The Madonna of Monaco was the subject of critical debate in the early twentieth century, both with regard to its dating and, on the other hand, its autography (although on the latter the critics are now basically unanimous in assigning the work to the master of Cortona), and above all with regard to the significance of the nude behind the protagonists, which could be interpreted as a neophyte about to undress to receive the sacrament of baptism, according to a hypothesis already in vogue in the early twentieth century and difficult to dispute. This presence moreover returns in Arcevia’s Baptism of Christ, also in the exhibition.

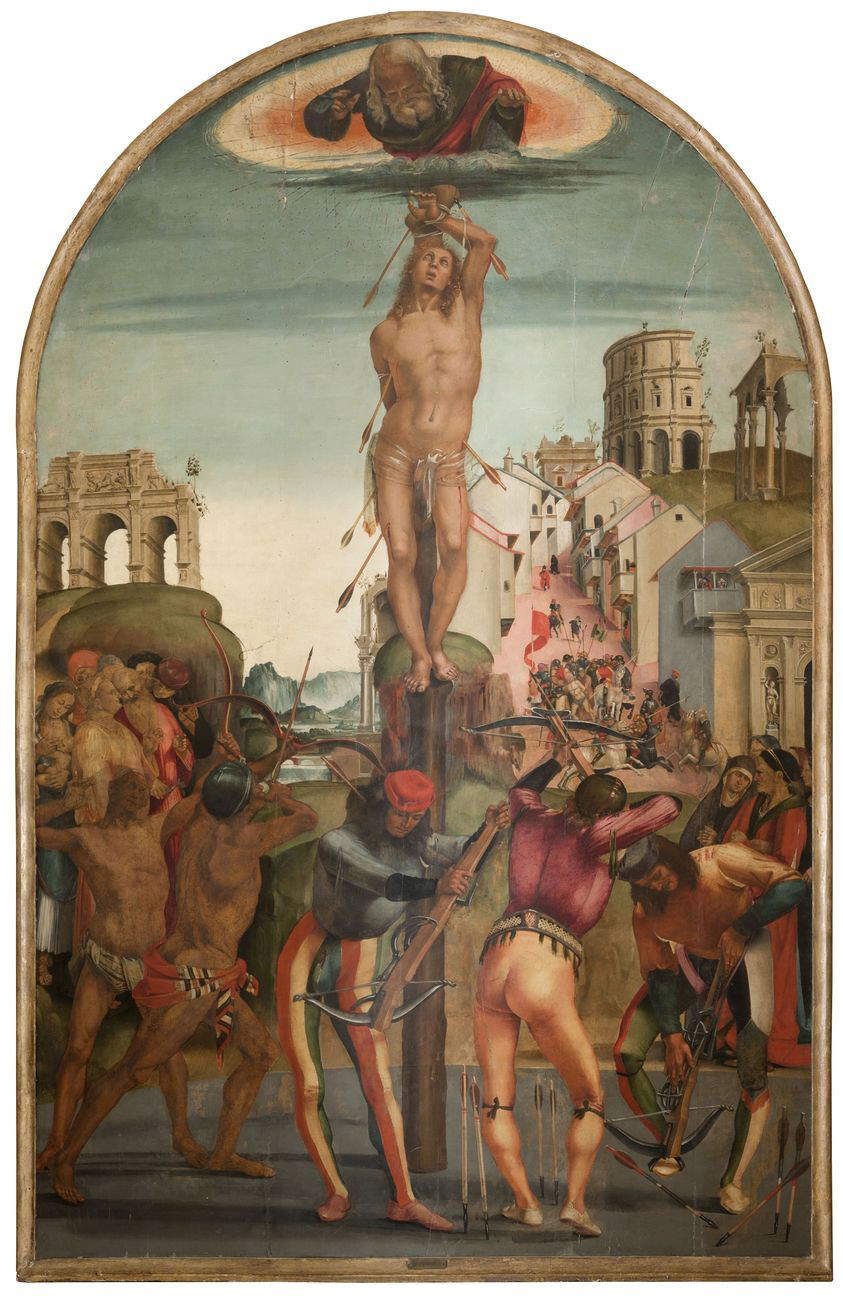

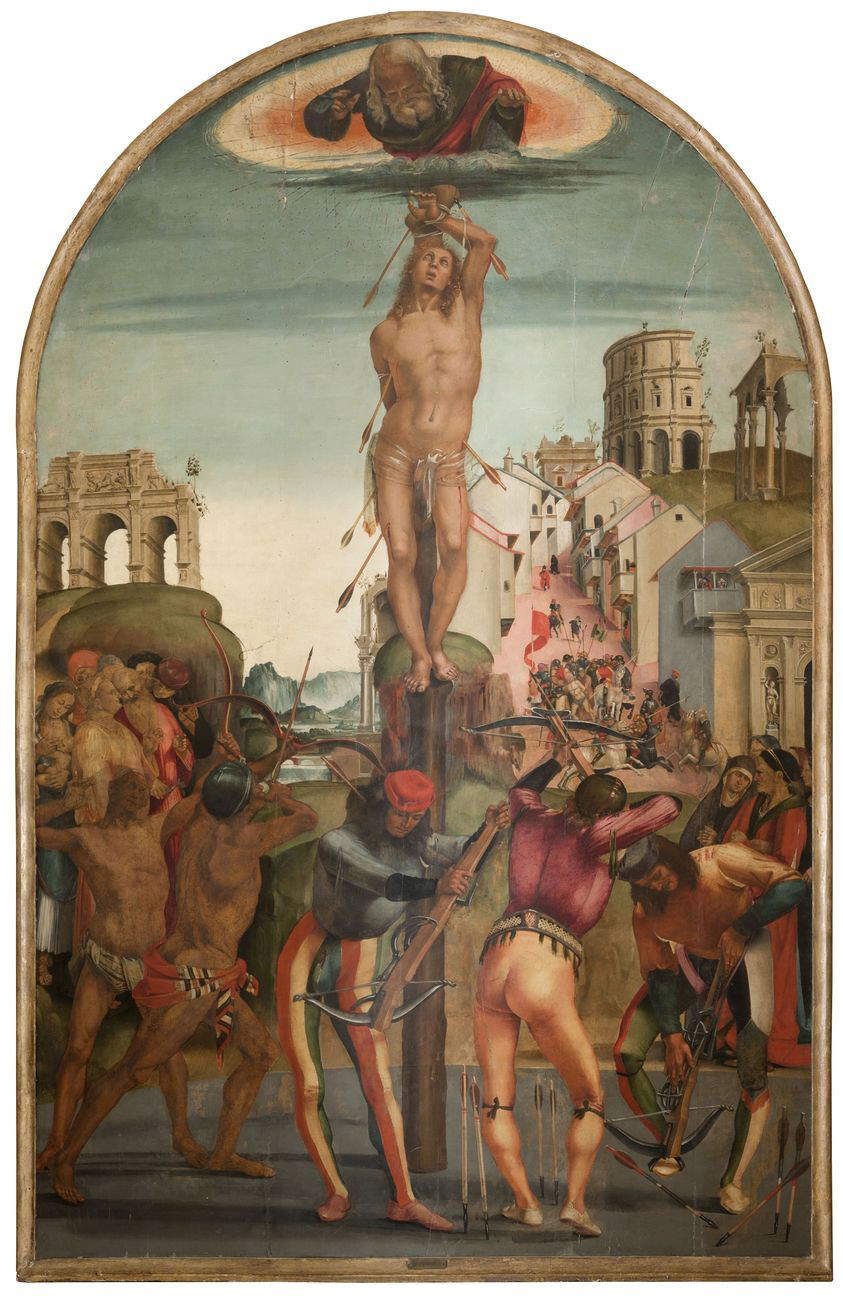

Signorelli’s interest in Roman antiquities, however, goes far beyond mere quotations or formal revivals. It is certainly necessary to reiterate that, with regard to his first Roman sojourn, we have no documents that can provide us with certain evidence, nor have any drawings survived that can hand down to us more precisely what the objects of his attentions were. Likewise, it should be noted, as scholar Eloisa Doidero points out in her catalog essay, that “the encounter with Rome’s ancient heritage is mediated, in Signorelli’s work, by the lesson of the Florentine masters, who introduce the painter to the study of anatomy and the naturalistic rendering of the body. The result is a formal language permeated with classical suggestions, while in the sculptural, three-dimensional dimension of our figures lies the most incisive evidence of his familiarity with ancient statuary.” It is therefore mainly in the nudes and figures that we see the most substantial contribution captured from antiquity (the catalog mentions the Flagellation of Brera, the Sistine frescoes themselves, the Medici Madonna, theEducation of Pan, and several other works that do not appear in the review, and one could extend the reasoning to Annalena’s own Crucifixion, which is instead present), but not only that. There are at least two other reasons that should be mentioned: the first is what Francesca de Caprariis, in her contribution to the catalog, calls the “rhetoric of ruins,” of which we find a formidable essay in Città di Castello’s Martyrdom of St. Sebastian, restored just for the exhibition. Here, Signorelli creates a landscape of ancient ruins that is certainly completely unrealistic, but which represents a profound and tangible sign of his passion for antiquities: thus, on the hills that serve as the backdrop to the main scene, we admire the Colosseum, a reworking of the Arch of Constantine, what appears to be the top of the Tower of the Militia. The latter appear to be infested with vegetation, as was typical of that rhetorical “sign of admiration and triumph over a past world” (so de Caprariis), while the same is not true of the temple facade in the foreground and the bridge in the background: here, the absence of the weeds could become a symbol of an antiquity lifted from oblivion and recontextualized in contemporary Christianity. The second motif, on the other hand, is thearchaeological interest exemplified by the titulus crucis that Signorelli affixes to the cross of Christ in Annalena’s Crucifixion: in fact, in 1492 what was believed to have been the plaque actually hung on Jesus’ cross as a sign of mockery had been found in Rome, and Signorelli may have been the first artist to have reproduced the famous trilingual inscription (in Hebrew, Latin, and Greek) in a work of art (the record is disputed with Michelangelo’s Crucifix of Santo Spirito).

|

| Roman art, Spinarius (second half of the 1st century BC; bronze, height 73 cm; Rome, Capitoline Museums) |

|

| Roman art, Spinario (early imperial age; marble, height 84 cm; Florence, Uffizi Gallery) |

|

| Luca Signorelli, Madonna and Child with Male Nude (1494-1496?; oil on panel, diameter 87 cm; Munich, Alte Pinakothek) |

|

| Luca Signorelli, Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian (1498; oil on panel, 288 x 175 cm; Città di Castello, Pinacoteca Comunale) |

|

| Luca Signorelli, Baptism of Christ (1508; oil on panel, 244 x 160 cm; Arcevia, Collegiate Church of San Medardo) |

|

| Luca Signorelli, Crucifixion with Magdalene, also known as Crucifixion of Annalena (1496-1498?; oil on canvas, 249 x 166 cm; Florence, Uffizi Gallery) |

A passage on the frescoes in the Chapel of San Brizio painted between 1499 and 1504, with the reproduction (on an obviously reduced scale) of some details of the scenes (a presence justified on the basis that the repertoire of nudes exhibited in Signorelli’s compositions in Orvieto derives from his knowledge of antiquity) allows the curators to display the so-called Orvieto tile, which introduces the sections on critical fortune, since the debate around the autography of this singular slab exacerbated tempers on the occasion of the 1953 monograph, decreeing a halt to the acclaim the artist had gained among scholars. The Roman exhibition limits itself to providing a few, very sketchy hints on the affair, which had already been covered (in greater depth) in the 2012 exhibition: summarizing, the tile (a tile on which are painted, on the front side, the portraits of Luca Signorelli and Niccolò di Angelo Franchi, chamberlain of the Opera del Duomo of Orvieto at the time when the artist was entrusted with the frescoes of the Last Judgment) became in fact a real scapegoat that opened to bitter attacks against both the curator of the exhibition, Mario Salmi, as well as of Signorelli himself, a painter whom, according to detractors, the exhibition wrongly exalted as “a man all sense and physicality, superb in his dilated muscles, schematic in his pseudo-epic massiveness” (so wrote a barely 22-year-old Alberto Martini, the student of Roberto Longhi who died prematurely at the age of 34, in 1953). Francesco Federico Mancini wrote in 2012 that in this chorus of criticism, in a certain way inspired by Longhi and capable of including personalities such as Ragghianti, Salvini and Castelnuovo, “years and years of personal grudges, of different methodological approaches, of contrasts between groups, of rivalry between schools of thought, of different ways of understanding and interpreting art” were poured out: Longhi was particularly fierce about the tile, which he hastily branded as a nineteenth-century fake. An impassioned defense by Mario Salmi ensued, but the question of the tile’s autography remains essentially unresolved: partly because the 1953 controversy almost completely truncated the debate (it was followed only by the stances of Scarpellini, who in 1964 remained equidistant, Zeri, who in 1995 spoke in favor of Signorelli, and McLellan and Henry who expressed their opposition in the late 1990s and early 2000s), partly because the affair is complex and difficult to summarize here (it will be worth mentioning, however, that the last position, that of the aforementioned Mancini, is in favor of a Signorellian autography).

Having thus touched for a moment on the theme of the consideration Signorelli enjoyed among critics, the exhibition returns to the artist, and does so with a room devoted to the theme of the “grace of invention” (to use a Vasarian expression) of the Cortona artist: one struggles indeed to follow the common thread of the exhibition, because this section for the most part deviates from it, tending as it does to give an account, by contrast, of the artist’s profile (Federica Papi justifies the presence of these Madonnas as works in which the tension of Orvieto’s nudes is diluted by opening up to a strand in which the artist “reveals his ingenuity and willingness to break away from tradition to undertake new solutions, formal, stylistic and conceptual”). Three Madonnas thus parade (too bad for the reflective glass that prevents them from being seen optimally), all belonging to different phases of Signorelli’s career: the Madonna and Child with Saints John the Baptist and a Saint, made in the late 1980s and housed in the Pallavicini-Rospigliosi collection; the Jacquemart-André Madonna and Child, St. John and an Old Man, executed in the early 1990s; and finally the Madonna and Child of c. 1505-1507 now in the Metropolitan Museum in New York. The Jacquemart-André Madonna, with the enigmatic presence of the unidentified elderly man (it is perhaps a shepherd), is not even among the artist’s best works (the figure of the Virgin slavishly traces the Madonna of theAnnunciation in Volterra, so much so that some have speculated that this work was made with the help of the workshop), while more interesting are the others, particularly the New York one, especially because of its history: the artist gave it to his daughter Gabriella in 1507, but perhaps it was originally intended for his wife Gallizia, who died prematurely in 1506 (a date after which the painter bound the painting to his daughter through his will). The unusual background of the panel, a decoration reminiscent of that of textiles, made up of roundels with putti (winged and otherwise) and medallions with profiles of emperors, in this case Domitian and Caracalla (thus, further references to Luca Signorelli’s interest in classicism, again animated, however, more by formal and symbolic intentions than archaeological rigor, since these coins are inventions of the artist), might allude to the theme offamilial love. The Virgin Mary herself exudes a humanity that is rarely found in homologous paintings by the Tuscan artist (one will also note the absence of haloes): it is presumable that Signorelli’s intention was to lend a character of universality to the figure of the Virgin, who in this painting takes on more the features of a caring mother than those of the mother of God. Thus a painting that tells a moving story, and a painting that stands as a rare testimony of a Renaissance work closely linked to the personal story of the artist who executed it.

|

| Attributed to Luca Signorelli, Tegola di Orvieto (c. 1504; fresco on brick slab, 32 x 40 cm; Orvieto, Museo dell’Opera del Duomo) |

|

| Luca Signorelli, Madonna and Child, St. John and an Old Man (c. 1491-1493; oil on panel, 102 x 87 cm; Paris, Musée Jacquemart-André) |

|

| Luca Signorelli, Madonna and Child (c. 1505-1507; oil and tempera on panel, 51.4 x 47.6 cm; New York, Metropolitan Museum) |

As the review draws to a close, we quickly touch on the only evidence of the artist’s two subsequent presences in Rome: the first is in 1507, the year in which, according to the account of the painter Giovanni Battista Caporali (Perugia, 1475 - c. 1560), Signorelli is said to have attended a dinner at Bramante’s house along with Perugino, Pinturicchio and Caporali himself, probably to discuss work, perhaps a project to submit to the new pontiff, Julius II (Albisola Superiore, 1443 - Rome, 1513), whose taste, however, would famously take other directions (and this despite the fact that the pope was initially in favor of having his apartments decorated by painters of the older generation, only to change his mind after noticing the young Raphael). The second, on the other hand, is the one mentioned in Michelangelo’s letter referred to at the beginning, but it is also known from another document, in which Signorelli is attested as the procurator of his daughter-in-law, Mattea di Domenico di Simone, in the context of a dispute in which the woman was opposed to the nuns of the convent of San Michele Arcangelo in Cortona, in 1513 (the datum coincides with Michelangelo’s account, who expressly recalls having met Signorelli in the first year of the pontificate of Leo X, precisely 1513). No other information about Luca Signorelli’s Roman sojourns is known at present.

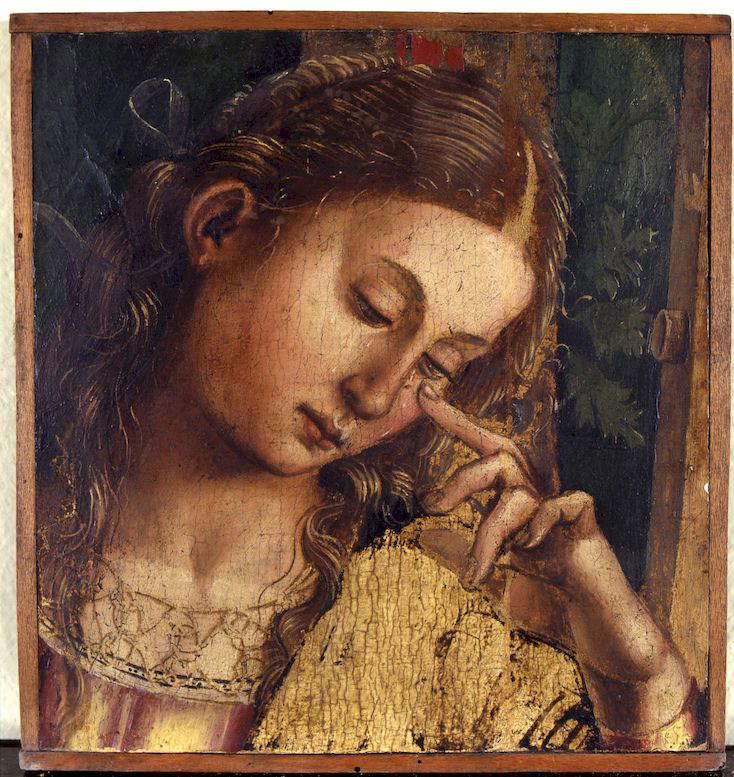

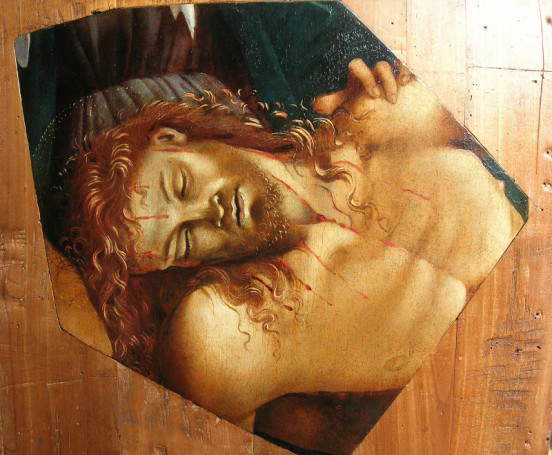

The finale is devoted to the reception of Signorelli’s art in art, criticism and the market between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. It begins with a brief, swift and, again necessarily incomplete, survey of the artists who were fascinated by his lesson, beginning with the engravers who reproduced the Orvieto frescoes (the itinerary includes works by Vincenzo Pasqualoni-Filippo De Sancits and Oswald Ufer) and ending with the works of Corrado Cagli (Ancona, 1910 - Rome, 1976) and Franco Gentilini (Faenza, 1909 - Rome, 1981) who, in the climate of rappel à l’ordre in interwar Italy would have looked, according to the curators, precisely at Signorellian nudes. In the catalog, the list of “debtors” goes on: it ranges from logical references (from Friedrich Overbeck’s purism to the visions of Claudia Rogge, whose references to Signorelli in her 2011 series Everafter have been seized upon by many) to instead more unlikely ones( Chapman Brothers’Fucking Hell ). As for critical fortune, its history is briefly traced, starting with Vasari and continuing through the long seventeenth- and eighteenth-century silence that, except for a few sporadic appearances (at least Agostino Taja who, in 1750, considered Signorelli the most talented of the Sistine artists, and Domenico Maria Manni who in 1756 discovered some documents about him, should be mentioned) lasts until 1791, when Guglielmo della Valle reevaluated Signorelli in his Storia del Duomo di Orvieto, to the late nineteenth century by Crowe and Cavalcaselle, by Robert Vischer author of the first monograph on the artist, by Maud Cruttwell, by Girolamo Mancini, and finally to the 1953 exhibition and from there to more recent events. This is also in order to introduce the theme of Signorelli’s rediscovery by the antiquarian market, which broadly coincided with the critical rediscovery. The renewed enthusiasm of antiquarians and collectors, however, was also detrimental to Signorelli’s works (as well as those of numerous other artists), since it led to the dispersion of several works and the destruction of others: exemplary is the case of the Matelica altarpiece, cut into several pieces to facilitate its sale (two fragments are on display in the exhibition, the Pia donna now preserved in the Collezioni Comunali d’Arte in Bologna and the Head of Christ in the Unicredit collection). Closing the circle, at the end of the exhibition itinerary, is the Madonna and Child among Four Saints and Angels, linked to Rome if only for the fact that it is kept at the National Museum of Castel Sant’Angelo, formerly owned by the Tommasi family of Cortona, which in the second half of the 19th century sold off a large part of its art collection (the pieces sold today are kept in museums and collections scattered around the globe). The work, which was donated to the Museo di Castel Sant’Angelo in 1928 by the Contini Bonacossi family, who owned it at the time, was originally executed for the convent of San Michelangelo in Cortona, exemplifies Signorelli’s late style (made up of monumental figures, in which the echo of ancient statuary can still be felt, and garish colors) and has an irrelevant predella (it tells the stories of St. John the Baptist, which is not present in the painting: the predella thus comes from another work and is the result of a later reassembly).

|

| Corrado Cagli, The Neophytes (1934; encaustic tempera on panel, 61 x 61 cm; Rome, Cagli Archive) |

|

| Luca Signorelli, Pia donna in pianto, fragment of the Matelica altarpiece (1504-1505; oil on panel, 24 x 27 cm; Bologna, Collezioni Comunali d’Arte) |

|

| Luca Signorelli, Head of Christ, fragment of the Matelica altarpiece (1504-1505; oil on panel, 26 x 28 cm; Bologna, Unicredit Collections) |

|

| Luca Signorelli, Madonna and Child among Four Angels and Saints (1515-1517; oil on panel transported on canvas, 189 x 176 cm; Rome, Museo Nazionale di Castel Sant’Angelo) |

A minor weakness of the Roman exhibition lies in the fact that it seems to deal somewhat hastily with the subject of the philosophical and allegorical implications of ruins in Luca Signorelli, entering into the merits only with regard to Saint Sebastian. There is talk of “redeemed antiquity” from a contemporary perspective, but there could also be more: Francesco Scoppola wrote that Signorelli’s ruins might allude “to the inexorable passage to which we are all called by time, but on closer inspection they also refer to the entire journey we must face in the course of life and not only to its outcome, until becoming [....] almost means, the instrument of every birth, every project and every goal” (whether one wants to agree or disagree with such a reading, a discussion around this topic could be fascinating). However, the Capitoline Museums’ exhibition works very well in highlighting Luca Signorelli’s contribution to the history of art: perhaps it might be an exaggeration to say that without him we would have had neither Raphael nor Michelangelo, but it is now well established that the relevance of his contribution was of enormous magnitude, and the exhibition succeeds well in highlighting the relationships that the art of the two great artists of the mature Renaissance had with that of the Cortona artist. In particular, it reiterates the role of indisputable precedent that the frescoes of the Chapel of San Brizio played for the Last Judgment that Buonarroti would paint some thirty years later in the Sistine Chapel, precisely where Signorelli had worked fifty years earlier, but not only that: certain iconographic solutions employed by Signorelli (the baby Jesus standing in the Manchester Madonna, the classical nudes behind the Holy Family, the attitudes of the Medici Madonna or the Madonna of Monaco) would provide more than a little food for thought for Raphael and Michelangelo. Of course, there is not much that has not already been said, and for this reason the main contribution of Luca Signorelli and Rome. Oblivion and Rediscovery should be read with the intention of tracing all these suggestions back to the Roman matrix, to the primigenial attention to the ancient, to the “ingegno et spirto pelegrino” that Giovanni Santi attributed to Signorelli and that enabled him to filter through his talent and his brush the impressions that the sight of ancient Rome aroused in him.

A mention, in conclusion, of the exhibition’s nimble catalog, published by De Luca Editori in an unusual 22x22 square format that certainly makes it very handy (and in this it is similar to historical exhibition catalogs ) but at the same time penalizes somewhat the rendering of the photographs of the larger works (one struggles a bit to capture details). The essays that make up the volume essentially follow the order of the exhibition, delving into its themes: the decision not to publish the works’ files is singular (but completely understandable, since the last exhibition on Signorelli was seven years ago and since then no impactful new works have been produced), and the idea of interspersing the essays with in-depth “boxes” of one or two pages, on individual themes, is intelligent, making for a more lively reading experience. The result, finally, is a useful tool for further study of Luca Signorelli.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.