It must not have been easy to be the nephew of Antonio Canal, better known as il Canaletto (Venice, 1697 - 1768), one of the greatest Venetian vedutisti, who immortalized landscapes of the lagoon on canvas; however, Bernardo Bellotto (Venice, 1722 - Warsaw, 1780) earned a respectable artistic career, managing not to fall into his uncle’s shadow. Indeed, the risk was that of not standing out from the great artist, of being continually compared to him, in a comparison where Bellotto could be the less successful painter, but he actually did not experience this kinship badly; on the contrary, he often signed his name “Io Bernardo B. detto il Canaletto,” evidence of a good relationship with his master.

As a child he presumably frequented his uncle’s studio, where the latter depicted those spectacular scenes with views that we have all seen live or in books, but it was around 1736 that Bellotto began his apprenticeship with Canaletto, beginning to become familiar with the representation of the master’s typical perspective architectures . Moreover, the most important members of theVenetian cultural milieu, as well as British nobles and Grand Tour travelers, passed through that studio. Venice and his uncle’satelier were therefore places of great cultural and artistic ferment, where he had the opportunity to learn and take his first steps in the world of art, gradually showing his progress both to his family members and to the personalities of that environment, but the leap came in 1740, when Bellotto moved to Tuscany for a stay first in Florence and then in Lucca. It is to this period that the Ragghianti Foundation in Lucca decided to dedicate the exhibition Bernardo Bellotto 1740. Viaggio in Toscana, which can be visited by the public until January 6, 2020. The curatorship is by Bożena Anna Kowalczyk, among the world’s foremost experts on Canaletto, and one notices the care with which the latter has crafted a small, concentrated, but very refined exhibition, both in the exhibition and layout and in the apparatus, as well as in the exhibition catalog itself entirely written by her, which contains an introductory essay and fact sheets of all the works on display; and even of works that the curator has included in the catalog to better understand some aspects of Bellotto’s context and production, but which are not present in the exhibition.

|

| Exhibition hall Bernardo Bellotto 1740. Journey to Tuscany |

|

| Exhibition hall Bernardo Bellotto 1740. Journey to Tuscany. |

Authors, before Bellotto, of most Venetian views were Luca Carlevarijs (Udine, 1663 - Venice,1730) and Canaletto, and both were present in Lucca’s eighteenth-century collections, particularly that of Stefano Conti: the merchant owned contemporary paintings, only of the Venetian and Bolognese schools, except for Guercino and Correggio. The most “fashionable” artists at that time were hired by the Veronese painter Alessandro Marchesini, and subsequently Conti commissioned paintings from them. Among the first painters of the Venetian school to be introduced to the latter’s gallery was Carlevarijs with three views of the city in the lagoon, while Canaletto was chosen because, as we read in a letter addressed to Conti written by Marchesini, “Mr. Lucca Carlevari” is “surpassed in greater esteem by Mr. Antonio Canale, who makes in this country universally stun everyone who sees his works, which consists on the order of Carlevari but one sees there lucer within the sun.” This is the starting point for the current Lucca exhibition, thus giving the first evidence of the connection between these artists and the city: the work by Carlevarijs, Il Molo con la Libreria e la Zecca verso la Punta della Dogana e la Salute, Venice, from 1706, opens the exhibition. A painting made by applying the rules ofoptics and perspective, following in the footsteps of Gaspar van Wittel, and using the camera ottica, as well as a series of small figures that belonged to a frequent repertoire of his paintings. The artist himself described the work in the documented attestation he made to Stefano Conti that he had depicted “the pescaria of Venice with the Frabica della Ceccha, is Publichi granaries, with a part of the Grand Canal, beyond which one can see the Church of Santa Maria della Salute, et la Dogana di Mare, with Barche d’ogni sorte, is quantity of figurines.”

Instead, Conti commissioned Canaletto to paint two pairs of views of Venice: two of the Grand Canal, one of the Rialto Bridge and one of Campo Santi Giovanni e Paolo, but none of these can be seen in the exhibition. Canaletto also made use of the camera ottica , and a small specimen, portable and therefore usable in the open air, which bears the inscription “A.Canal” on the flap and which comes from the Correr Museum in Venice, is here on display: an instrument that Bellotto also learned about in his uncle’s studio. Its operation was similar to that of the human eye, that is, the image was projected onto a glass screen placed in the upper part of the optical chamber; reflecting the image, introduced through a hole with a concave lens, was an internal mirror; by placing oily, transparent paper on the glass it was possible to draw the outlines of the image, reflected inverted. Fundamental to the execution of a painting was drawing: Bellotto learned very skillfully from his master the perspective techniques at the basis of his views, which he accomplished with the help of tools, such as the compass and ruler, useful for constructing references for the entire composition of the work, such as the line of the horizon that pulled from one edge to the other. This aspect is very evident in the drawing on display from the Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe of the Uffizi, depicting The Arno towards the Ponte alla Carraia, Florence: the use of the compass is clearly visible in the drawing of the bridge, and the ruler not only in the main construction lines, but even in the windows of the houses. It is in fact theonly known Florentine drawing and is the composition for the later painting of the same name in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge. There is evidence in numerous sketches and reproductions of his nephew’s great ability to bring back to the paper the details of the architecture and to outline the contours of the small characters depicted, as his master did, but in the paintings he took it a step further: he used the technique of etchings impressed on the canvas with the tip of the brush handle, especially in the discolorations, to increase the intensity of the painting. The knowledge and techniques he learned from Canaletto therefore served as a starting point from which to build his own identity, to begin to differentiate himself from his master.

|

| Camera ottica that belonged to Canaletto (18th century; wood, glass and mirror, 38 x 24.2 x 22.5 cm; Venice, Museo Correr, inv. C1 XXIX, s.n. 30) |

|

| Luca Carlevarijs, The Pier with the Mint and the Bookshop, Westward, Venice (1706; oil on canvas, 63 x 92 cm; Lucca, Museo Nazionale di Palazzo Mansi, inv. 751) |

As already stated, Canaletto’s studio was frequented by leading figures in the Venetian cultural milieu, among them Anton Maria Zanetti di Girolamo (Venice, 1706 - 1778); a collector and antiquarian, he had become a sort of agent for the artist, thanks to whom the latter obtained important commissions from the Anglo-Saxon world in particular. Linked to Zanetti was another prominent personality, Marquis Andrea Gerini, who came from a family of merchants and bankers connected to the Medici and Lorraine families; Zanetti soon became the marquis’ main artistic adviser, taking charge of updating his pictorial collection with paintings by contemporary Venetian artists and carrying on with Gerini the two series of prints devoted to the nascent vedutismo fiorentino, entitled Scelta di XXIV vedute delle principali contrade, piazze, chiese e palazzi della città di Firenze and Vedute delle ville e d’altri luoghi della Toscana.

Zanetti and Gerini decided to focus precisely on Bellotto: in fact, this is the first documentation of Bellotto’s Florentine Vedutismo, and moreover they agreed to send the young artist to Florence with the risky, but fortunate, idea of bringing eighteenth-century Florentine Vedutismo to life from Canaletto’s techniques.

After a first section of the exhibition thus focused on the context within which Bellotto moved in the initial phase of his production, recalling his relationship with his uncle-master, the exhibition enters the heart of the period in which the artist left Venice to come to Tuscany, at first to Florence. Of his Florentine activity there are precise testimonies: “Io appié sottoscritto ho ricevuto dall’Illustrissimo Signore Marchese Andrea Gerini Zecchini ottantaquattro, e paoli 18 - per valuta di 4 - quadri di vedute vendutili, e fattigli a posta per detto prezzo di accordo a me contanti --- Zecchini 84. 18 - Io Bernardo B. detto il Canaletto.” The document is dated September 30, 1740, when Bellotto was already in Florence, since he arrived there after April 22 of that year. These paintings include The Arno at the Tiratoio towards the Ponte Vecchio and The Arno from the Vaga Loggia, with San Frediano in Cestello, both in a private collection and not in the exhibition, but carefully listed in the catalog. They are a “complementary pair,” as the curator calls them, since in the former the Arno is depicted upstream from the Ponte Vecchio, while in the latter it is depicted downstream. They are the earliest documented and precisely dated works by the artist, and the certainty that these are two of the four works the artist refers to in the aforementioned document is due to the reconstruction of their antiquarian history: they were part of Otto Beit’s collection, but suffered a series of thefts beginning in the 1960s that damaged the first painting in particular (during the last theft, the painting was removed from the frame and rolled up, resulting in the loss of color fragments). Thanks to the recent discovery of payment receipts in the Gerini archive, it was possible to identify the paintings in the Beit collection with the two views of Florence that appeared on March 8, 1879, accompanied by the words “From the Gerini Collection” and with Canaletti’s name in London, at Christie’s, and on May 3, 1884, mentioned in the same way, again at Christie’s; moreover, the sales code 233 T stamped on the only old frame of the pair of paintings, namely that of the second one, attests them as the paintings from the Beit Collection. Model for The Arno from the Wandering Loggia was a drawing by Giuseppe Zocchi (Florence, 1717 - 1767), the Gerini house artist who, according to the latter’s and Zanetti’s intentions, was to learn the techniques of vedutismo from Bellotto. The other two paintings commissioned by the marquis remain unknown to this day. Displayed instead in the exhibition are other views of the Arno: The Arno from the Ponte Vecchio to Santa Trinita and the Carraia, Florence, from the Szépművészeti Museum in Budapest, characterized by the row of illuminated houses on the Arno, is complementary to the painting from Cambridge made in 1743-44, The Arno to the Ponte Vecchio, Florence, built almost symmetrically to the former, but its pendant (since they both belong to the collection of Marquis Vincenzo Riccardi registered in 1741) is Piazza della Signoria, eastward, Florence, housed in the same Budapest museum. In the two Budapest paintings, Bellotto depicts the Arno as if it were a Venetian canal, to which he adds greater contrasts of light and a hint of aerial perspective regarding the more distant elements.

|

| Bernardo Bellotto, LArno verso il ponte alla Carraia, Florence (1743-1744; oil on canvas, 73.7 x 105.4 cm; Cambridge, Fitzwilliam Museum, inv. 195) |

|

| Bernardo Bellotto, LArno verso il Ponte Vecchio, Florence (1743-1744; oil on canvas, 73.3 x 105.7 cm; Cambridge, Fitzwilliam Museum, inv. 192) |

|

| Bernardo Bellotto, LArno dal Ponte Vecchio fino a Santa Trinita e alla Carraia, Florence (1740; oil on canvas, 62 x 90 cm; Budapest, Szépművészeti Múzeum, inv. 647) |

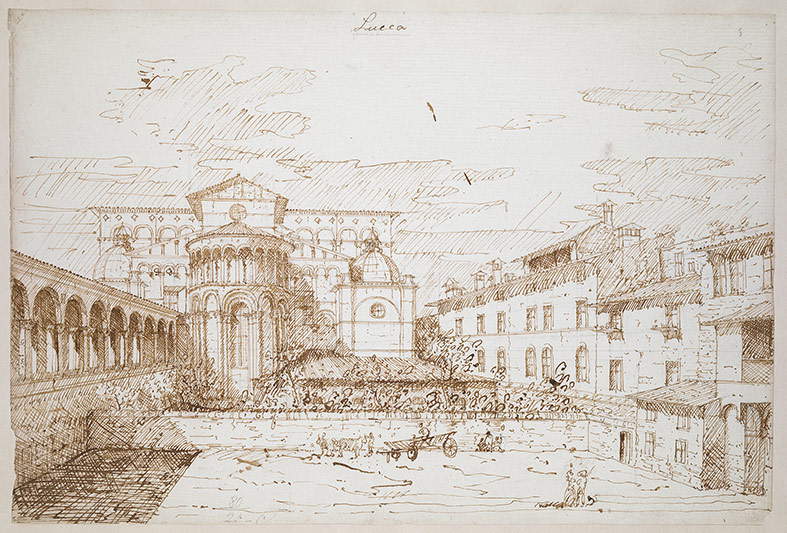

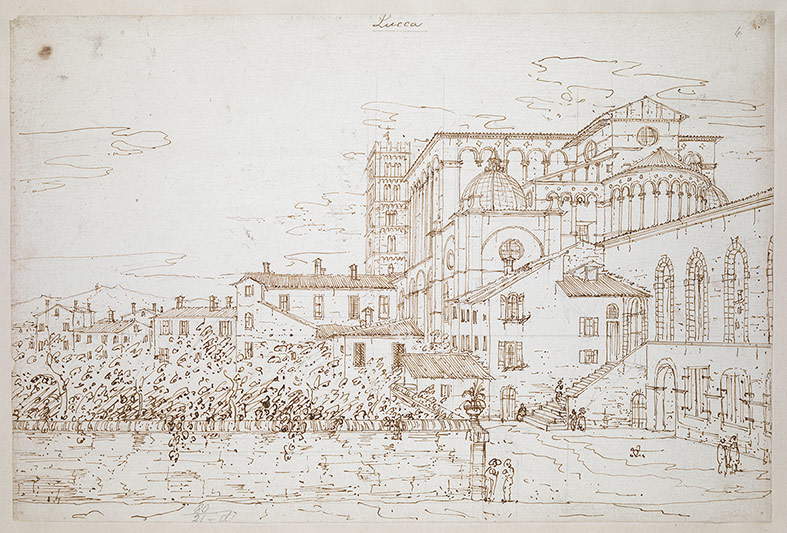

The exhibition closes with the section devoted to the artist’s relationship with Lucca, the city where the same exhibition is held. And it is in this section that the real protagonist of the entire exhibition is placed: Piazza San Martino with the cathedral, Lucca, from York. Bellotto arrived in the Tuscan city in September-October 1740, and there is evidence of his artistic activity in Lucca in the painting just mentioned, which is in fact the only known painting of the city, and in the four accompanying drawings belonging to the topographic collection of King George III. Thus, looking at these four drawings and this painting provides a detailed and precise understanding of how the famous square of Lucca and its surroundings really looked at that time: in fact, the drawings depict the various perspectives from which the cathedral is viewed, namely frontally (as in the drawing), the flank with San Giovanni from the Piazza degli Antelminelli, and the apsidal part with the addition of the bell tower.

In making the painting, the artist carefully studied the scene from a window on the piano nobile of the Bernardi palace, and the stylistic similarity in size and colorism to the pair of paintings in the Beit collection has suggested a chronological proximity to the Florentine sojourn (perhaps having received a loan of twenty zecchini from Gerini on August 30, 1740). The corresponding drawing is but a sketch: in the painting, the artist meticulously dwells on every detail, even the shadows, clouds, vegetation, and stones scattered on the beaten ground, and the small figures of the characters inhabiting the scenery of the square are painted at the tip of the brush. From a perspective point of view, the work is reminiscent of the Florentine Piazza della Signoria depicted in the Budapest painting: the Palazzo Vecchio results in a frontal position similar to the Cathedral of San Martino, while the houses on the left and the Loggia dei Lanzi on the right are comparable to the perspective of the buildings surrounding the square in Lucca.

|

| Bernardo Bellotto, Piazza San Martino with the Cathedral, Lucca (1740; oil on canvas, 50.8 x 72 cm; York, York Art Gallery, inv. YORAG 771) © York Museums Trust |

|

| Bernardo Bellotto, Piazza della Signoria, Florence (1740; oil on canvas, 61 x 90 cm. Budapest, Szépm&x0171;vészeti Múzeum, inv. 645) |

|

| Bernardo Bellotto, Piazza San Martino with the Cathedral, Lucca (1740; pen and brown ink, 25.3 x 36.8 cm; London, British Library, Maps Room, K. Top. LXXX-21a) |

|

| Bernardo Bellotto, San Giovanni from the Piazza degli Antelminelli, with the side of the cathedral, Lucca (1740; pen and brown ink on pencil outline, 25.2 x 37 cm; London, British Library, Maps Room, K. Top. LXXX-21b) |

|

| Bernardo Bellotto, The Cathedral of San Martino, from the apsidal part, with the cloister, Lucca (1740: pen and brown ink on pencil trace, 24.8 x 37 cm; London, British Library, Maps Room, K. Top. LXXX-21c) |

|

| Bernardo Bellotto, The Cathedral of San Martino from the apsidal part with the bell tower, Lucca (1740; pen and brown ink on pencil trace, 24.7 x 36.7 cm; London, British Library, Maps Room, K. Top. LXXX-21d) |

|

| Bernardo Bellotto, Santa Maria Forisportam, Lucca (1740; pen and brown ink on pencil trace, 23.5 x 37.1 cm; London, British Library, Maps Room, K. Top. LXXX-21e) |

Bellotto’s plan to capture the cathedral from four different viewpoints was an absolute novelty in Vedutism, which he replicated on other occasions: between 1756 and 1758 in his views of the fortress of Königsteinand between 1776 and 1777 in his paintings of Wilanów Castle.

There is also another drawing of the city of Lucca, which, however, does not concern the Cathedral of San Martino, but another Romanesque church: Santa Maria Forisportam, now kept in the British Library in London.

The Lucca sojourn must also have been arranged by Zanetti and Gerini, who contacted a mutual “friend of theirs from Lucca,” but the latter has not yet been identified.

The exhibition has the merit of having presented the beginnings of Bernardo Bellotto’s career and his turning point accomplished with the trip to Tuscany, first to Florence and then to Lucca, giving birth to Florentine vedutismo, within which he succeeded in adding novelty to the techniques learned in the study of Canaletto. Moreover, the curator, as already established among the leading experts on Canaletto, has done recent research that has made it possible to identify the Beit paintings with those commissioned by Gerini.

This is a journey through eighteenth-century Tuscany through which the visitor is accompanied by one of the most significant artists and vedutists on the Italian scene.

The author of this article: Ilaria Baratta

Giornalista, è co-fondatrice di Finestre sull'Arte con Federico Giannini. È nata a Carrara nel 1987 e si è laureata a Pisa. È responsabile della redazione di Finestre sull'Arte.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.