Enzo Azzoni, a ninety-five-year-old Verbano photographer and runner who at his young age still continues to win Italian masters championships in track and field, is right. He is right when he says that we must not forget that today we can know and appreciate the art of Paolo Troubetzkoy, who is among the greatest sculptors of the early 20th century, thanks in part to the work of Luigi Troubetzkoy, his brother, who worked hard to ensure that the family legacy was not lost. Azzoni said this a few days ago in an appeal to La Stampa, while in Paris, these weeks, all visitors to the Musée d’Orsay are hurling themselves between the rooms of the exhibition(Paul Troubetzkoy. Sculpteur) which, the effective presentation says, “traces the extraordinary career of this Italian artist, Russian prince by birth and Parisian by adoption, who had at the same time a brilliant career in the United States.” He was actually born in Intra, a Piedmontese shore of Lake Maggiore, had just the Russian origins but when he went to work in the land of his parents he did not speak a half a word of his father’s language, and he had gone to France because, like all artists at the time who wanted to have a minimum of international consideration, Paris was an inescapable destination. Troubetzkoy was a kind of art commuter, if you will. Like those who today move to Milan for work. However, it is true that in Paris he had the keys to all the salons, that he exhibited everywhere, that France opened the doors to America for him, and that without Paris his career would not have been the same. Toward the end of his career he had rented a small villa with annexed studio in Neuilly-sur-Seine, and in the summer, when he could, he returned to Lake Maggiore, where much of his production found a home precisely at the behest of Louis.

Paul Troubetzkoy had passed away in 1938, and his brother had inherited half of his remaining works. The other half had gone to his second wife, and Luigi wanted to prevent that half from being lost as well, so he bought it and then gave it all to the Museo del Paesaggio in Verbania, the artist’s hometown, where today the most important and most complete of his production, and which also served as the framework for the exhibition at the Musée d’Orsay, curated by Édouard Papet, Anne-Lise Desmas and Cécilie Champy, and which will then also have a second Italian stage in 2026, at the GAM in Milan, curated by Paola Zatti and Omar Cucciniello. There are almost fifty works that the Museo del Paesaggio in Verbania has loaned to the Musée d’Orsay, practically half the exhibition: the same core that will then be in Milan for the second installment. Besides, Azzoni said, we would have had much more today if, in March 1945, with the war almost over, the Black Brigades had not set fire to the house of Luigi and his wife. The problem, he recounted, was that the museum left much of that museum to languish in unsuitable storage conditions, and until the 1970s, when he and others put their hands on the layout of the rooms, Troubetzkoy’s works had ended up basically forgotten. Then, the rediscovery, which began in 1990 with an exhibition at the Verbania Museum, continued with Troubetzkoy’s presence in so many exhibitions devoted to the so-called “Belle Époque,” and culminated in this double exhibition at the Musée d’Orsay and the GAM in Milan, the first real opportunity for international redemption. It is a bit like bringing the artist back to his natural dimension. A successful sculptor, not as well known as others, yet capable of having marked an era, since he can be included without a shadow of a doubt among the most interesting portrait painters of his time, an indispensable witness to the social and cultural life of that era, connected with artists and men of letters (he was a friend, to name two, of Tolstoy and George Bernard Shaw), and was also a character, for his time, totally outside any canon: he was a vegetarian and loved animals to such an extent that he can be considered one of the first modern animalists (this is the main reason why his production abounds with animal sculptures).

An artist far from the academies and always close to the avant-garde. And that he had freed himself from any tradition to follow just his instincts had already been noticed, in theyear 1900, someone as great as Vittorio Pica, who in an article published in Emporium placed him at the head of young Italian sculpture, compared him to Rodin and Meunier, and believed that his sculpture had no Italian fathers or, if it did, it had to find them in painting (the name was Tranquillo Cremona, who rightly opened, along with other scapigliati, the Musée d’Orsay exhibition). In describing Troubetzkoy, Pica had resorted to a polemic by Huysmans, who in 1881 complained that sculptors did not dare to deal with contemporary life and the “elegant modern lady.” Huysmans should have, Pica said, “confessed that he had found in Troubetzkoy the daring and intelligent implementer of one of his ideals as a refined avant-garde art critic, and this without his having resorted either to wood, wax, or polychromy, means he had proposed to achieve an effective reproduction of the features, attitudes, and clothing of the woman of our times.” And he had succeeded with bronze, with his “impressionist technique of sculpture”: a definition, that of “impressionist,” widely employed by all the critics contemporary with him but which is perhaps not sufficient, as will be seen, to fully frame his production.

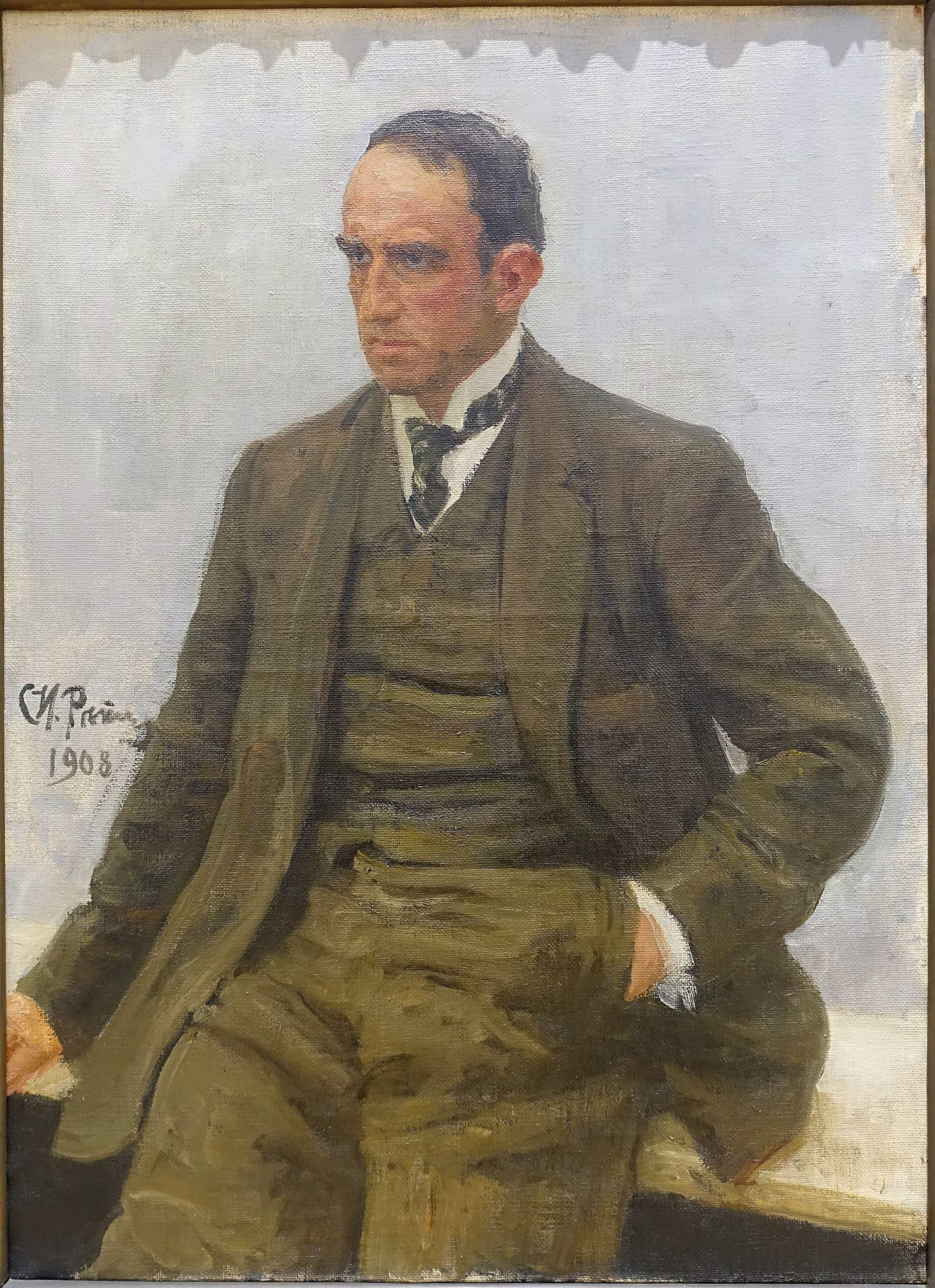

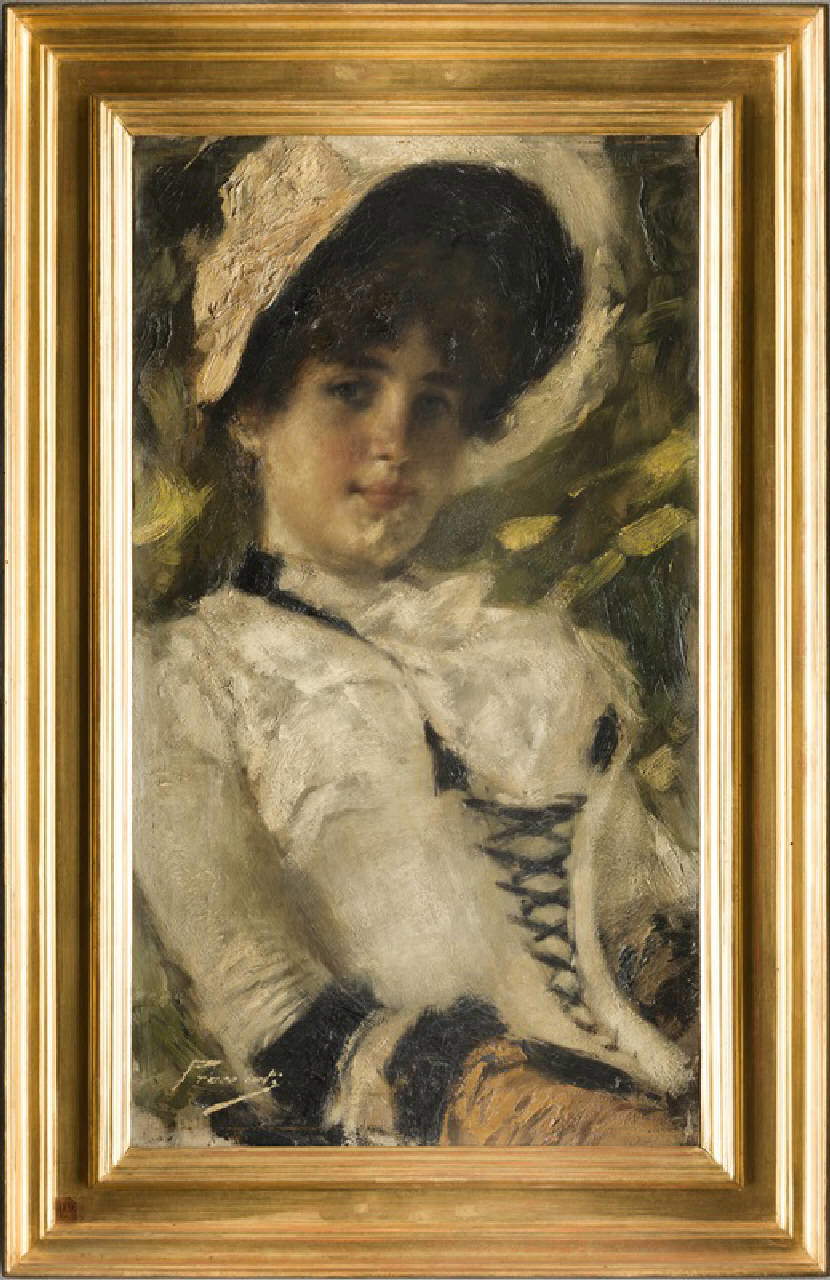

Troubetzkoy would make himself known early on as an experimenter, and that is how we get to know him in the exhibition, after an introduction with some portraits of him (from the GNAM in Rome comes one of his friend Il’ja Repin that shows us the sculptor at the age of forty, and we can also see Daniele Ranzoni’s portrait of him as a child with his brothers Pietro and Luigi and their dog) and of family members (including the beautiful 1911 bronze dedicated to his wife Elin): Spring, a work from 1895, also on loan from GNAM, a portrait of his sister-in-law Amélie Rives, is a kind of programmatic manifesto because of the way the figure of his brother Pietro’s wife is modeled. A painterly treatment, with the wavy, vibrating, flaking surfaces suggesting the idea of movement: we see it in the face, in the hair, but above all in the dress, raw, we even recognize the fingerprints of the artist who shaped the model with that spontaneity that would characterize almost all of his production (the comparison with the plasterSelf-Portrait of 1925, exhibited nearby, confirms that his way of working would remain almost unchanged for the rest of his career) and that allowed him to capture natural poses, fleeting moments, quick impressions. If we want, Troubetzkoy is an artist born out of the scapigliatura (and it could not be otherwise, since he lived in Milan for a couple of lustrums, from 1886 to 1896, and frequented those circles), with which he shares the desire not to give back to the relative a realistic portrait, but rather a psychological, nuanced portrait, a portrait of atmosphere. Yet, at the same time, he already looks to the Impressionists’ research: his work then can be compared to what Previati was doing in painting at the time, who is approached with one of his masterpieces from the pre-Divisionist phase, the 1881 Portrait of Erminia Cairati , and his brother Pietro, present with the 1882 Portrait of Mary Franckfort , also arriving from the Museo del Paesaggio in Verbania. Portraiture would soon prove to be Troubetzkoy’s most congenial genre: Thus parading through the exhibition are some of his most famous portraits, above all that of Gabriele d’Annunzio, which maintains the traditional bust-portrait form, or again the portrait of Erminia Cairati herself, one of Troubetzkoy’s not-so-frequent marble works, and then the portrait-statues, works in which the Verbania artist would specialize, those in which the subject is taken full-length. An example of this is Sola, a portrait of the young Milanese actress Emilia Varini, executed in 1893 and exhibited at the Milan Permanente Exhibition that year, where it was described by critics as “an exquisite figurine of an elegant young woman, with a stately imprint.”

What Troubetzkoy was trying to achieve with his portraits is something very similar to what Pica had summarized in his 1900 article: “Troubetzkoy [...] set himself, from his earliest trials, [...] to seek, with commendable ardor, something quite new and modern, proposing not only to portray with rare effectiveness the expressive mobility of the face, but also to give as much as possible, the optical illusion of movement.” The exhibition goes on to show the public some of the most important results of these experiments, beginning with the imposing portrait of his friend Giovanni Segantini, which surprises precisely because of its naturalness, and although it does not reach that degree of investigation into movement that had marked some of the works he had done in earlier years, it still stands at the pinnacle of his art. Contact with Segantini, however, must have suggested to him new possibilities for investigation: a work such as theWinter of 1894 reveals perhaps one of the closest points of rapprochement with Divisionist poetics, by virtue of that way of using light that paints the surface of the sculpture through a jagged and natural modeling in every minute element (and this is one of the reasons why it is difficult to say he was a fully Impressionist sculptor). Troubetzkoy could also afford to investigate and experiment all the time, since he came from a wealthy family, and therefore did not need to make art for a living. And this, moreover, is one of the reasons why that “Russian prince,” as he was roughly identified by so many of his contemporaries, was disliked by many of his colleagues who considered him little more than an amateur, if not an amateur tout court given also, one might say, his wholly anomalous educational itinerary, for after beginning the normal path of ’apprenticeship, first with Donato Barcaglia and then with Ernesto Bazzaro, dissatisfied with his masters he had continued as a self-taught artist, studying his models from life, and already in 1886, at exactly twenty years of age, he made his debut at Brera with the sculpture of a horse, while in 1891 he competed for the realization of the monument of Dante in Trento, although he would not make it to the final trio: on display in the exhibition, next to Segantini’s portrait, is the sketch he had made, and we can imagine that it was discarded because it was decidedly far from the rhetoric of the time.

Troubetzkoy’s idea was to capture life, to give the relative the impression that his figures were animated by a throb, that they were moving. Therein lay the reason for his success. His quest was not as radical as that of Medardo Rosso, an artist who could be juxtaposed with him: where the Turin artist sought a fusion of subject and atmosphere, a continuity between the figure and the air around it, with the result that the figure itself, in his works, falls apart and blends with its surroundings, Troubetzkoy simply aspired to a feeling of movement but wanted his figures to remain clearly recognizable. His sculpture was modern, certainly, but it was not subversive. And it is for this reason that he would have met with favor from a large patronage. Of course, the more open the subject matter, the more Troubetzkoy’s experimentalism increased: this dichotomy is well felt when the exhibition displays a short distance away the portrait of Count Robert de Montesquiou, dandy and poet (the exhibition also features the celebrated portrait of Giovanni Boldini), which is one of the works that comes closest to a poetic approachable to that of Medardo Rosso, with the nobleman’s clothes blending in with the armchair on which he is seated (although, again, the features of the subject remain closer close to those of realist sculpture than to Rosso’s Impressionism) and the statuettes of Mr. and Mrs. William Kissam and Virginia Graham Vanderbilt, who seem to have forgotten the lengths to which Troubetzkoy’s sculpture could go (evidently this rigidity, this fixity is due to the taste of the two patrons who must not have been ready for a particularly new sculpture). When, however, Troubetzkoy was free from the pressures of friends and patrons who asked him to be effigyed in bronze, then his sculpture again made an impression: next to the portraits see, for example, the Mother with Child executed in 1898 and exhibited at the 1900 Paris World’s Fair and considered one of the most poignant images of motherhood of the time, or the shortly later Child with Dog, on the dual theme of childhood and animals. The sculpture of Mother with Child had also impressed his contemporaries: Pica considered it to be work capable of exhaling a “so pure and moving poetry as to merit Troubetzkoy the title of sculptor of motherhood,” and juxtaposed with him that same Bambina col cane that is seen in the exhibition a little further on, deeming it a work akin to the one with Mother and Child in delicacy ofinspiration and for evidence of truth “in the caressing suavity of childhood with the good-natured tenderness of the beast most attached to man.”

Passing between the portraits of the more mature phase of his production (such as that of Luisa Casati, faithful to the lanky, lanky and mysterious figure of the marquise, further emphasized by the presence of a greyhound, or like the one, more late, of George Bernard Shaw, her longtime friend (and like him, moreover, a vegetarian), a sketch from which the monument to the writer that now stands in Dublin was made), there is time to see three thematic sections. The first is the one on the “American” Troubetzkoy and the Wild West statuettes: thanks to his Parisian acquaintances, the sculptor came into contact with several Americans who lived in France and facilitated his sojourns in the United States, where he went between 1911 and 1912 and then again between 1914 and 1920, to get away from Europe torn apart by World War I. And he had quickly become a star, partly because of his status as a prince who dabbled in sculpture, partly because of his ardent support for the vegetarian cause, and of course partly because of the power of his portraits. Fascinated by the Wild West, Troubetzkoy developed a production of Western-themed statuettes, portraits of Indians on horseback and cowboys, inspired mainly by Buffalo Bill’s shows, which were, moreover, quite successful: they are probably not among the most interesting achievements of his production, since they are the least spontaneous and somewhat more contrived and constructed statuettes of his output, but they are certainly also among the most entertaining. The second is devoted to another strand that the artist worked on in the United States, that of the dancers: these are also among his most famous and most replicated sculptures, works that give him the opportunity to work on the dynamism of bodies, the elegance of gestures, the essence of movement, all qualities that had ended up turning on critics. Works, admittedly, rather easy, prone to capture consensus, since often, especially in the later stage of his career, to pander to public taste Troubetzkoy did, roughly, what Boldini did in painting: sell essentially conventional works, enlivened by some effect that nevertheless recalled the avant-garde’s research, in order to give the recipient of the work the impression of having an updated masterpiece on his hands (despite the Danseuses finding favor with the public when the Futurists were already fully active, to say). Closing, finally, for the animalier sculptures, a genre that Troubetzkoy would practice throughout his career, as a lover of animals and as, one might say, a fervent animal lover: he had become one as a young man after witnessing the slaughter of some calves, something that made a considerable impression on him and also convinced him to become a vegetarian: there is also a polemical work in the exhibition, Devourers of Corpses, where a man intent on mauling a roast is contrasted with a wolf licking a bone to show that one, the animal, acts according to the law of nature, and the human being, on the other hand, acts against the law of nature. Gathered in the last room of the exhibition are several sculptures: the artist’s love for animals leads him to depict them with the same vividness, the same naturalness devoted to human beings, and in this genre he would even be considered unsurpassed by his contemporaries: here then are the bronze models of horses and elephants, here are the beloved little dogs of all breeds, from foxes to Pekingese through to bloodhounds, here is another work, The Faithful Friends, which takes up the theme of animal-friendly childhood, and finally, in the center of the room, here is the splendid Lamb, a 1912 work of astonishing realism, entitled How Can You Eat Me?.

Troubetzkoy’s critical fortune was certainly weighed by his origins, the fact that he did not have many collectors and that these collectors were largely Russian and American, to some extent his cosmopolitanism, and probably a certain ease and fidelity to himself that especially in the final stages of his career, those roughly coinciding with the American period and his return to Europe, weighed on that propensity for research that had made him stand out when he was young. He was born as a scapigliato artist, as a mediator between Italy and France, as a dissolver of form, and then became the sculptor of international worldliness, the perfect parable of theembourgeoisement de l’art d’avant-garde. Across the Alps he became “Paul” Troubetzkoy, and so the exhibition calls him, and perhaps an international exhibition, a new dialogue between Italy and France, was really needed to recover the story of this artist,

Pica, in his 1900 article, already complained about the poor reception Troubetzkoy had received and continued to receive in his native country. And he gave the example of the monument to Dante for Trento, which was rejected because the sketch had been conceived according to too unbridled an imagination, did not follow sufficiently pure lines and strayed too far from any classical tradition: baleful reasons, for Pica. To make up for the lack of success in his homeland, he had had to try to make a name for himself in Paris and St. Petersburg, where his flair would be better recognized. It certainly cannot be said that in even more recent years Italy has treated better than then this son of hers who, at least for a time, was as up-to-date as Italian sculpture had to offer and was considered an artist equal to a Rodin. And it is probably safe to say that we have not yet reached a full revaluation. It may be then that this time the process starts in France.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.