Collesalvetti ’s Pinacoteca Comunale “Carlo Servolini” (Municipal Art Gallery ) is hosting until Aug. 7, 2025 an exhibition intended to shed new light on a complex and still little-explored figure in the artistic and literary scene of early 20th century Leghorn: Aleardo Kutufá (Leghorn, 1891-1972). The exhibition, entitled The Hour of the Lamps. Dialogues of Aleardo Kutufá between D’Annunzio’s aestheticism, crepuscular ghosts and the dream of the Middle Ages, promoted by the Municipality of Collesalvetti and curated by Francesca Cagianelli with Stefano Andres and Emanuele Bardazzi, reconstructs the multifaceted nature of an intellectual whose work, although rewarded by considerable national acclaim in his day, has been unjustly relegated to oblivion.

Kutufà’s value was recognized by leading figures in Italian and European culture. Giovanni Marradi, the Livorno poet and patriot, called his books “a great revelation of ingenuity.” His friend the novelist Guido da Verona praised his work as “of high and musical value,” while Guido Mazzoni, a poet and politician, admired his “lofty writing qualities.” Even figures of the caliber of Gabriele d’Annunzio, Benedetto Croce, Arturo Graf and the famous composer Arturo Toscanini expressed flattering judgments about him, attesting to his intellectual and artistic stature. Despite this, his name seems to have been marginally questioned only in Gastone Razzaguta’s volume Virtù degli artisti labronici, while Carlo Servolini, in his Commedia Labronica delle Belle Arti, celebrated him in the “Parade of the Forgotten,” as a multifaceted artist and man of letters.

Born in Leghorn on Nov. 9, 1891, to an aristocratic family (Cavaliere Nicola Kutufà and Marchesa Gemma Turini Del Punta), Aleardo Enrico Leopoldo Paolo Kutufà cultivated throughout his life a deep pride in his origins and a firm spiritual bond with Ellas, wandering the Orient in its many forms: Greek, Byzantine, Turkish, and the fabulous one described in The Thousand and One Nights.

Kutufà’s cultural path was precocious. Enrolled at the Liceo Classico Niccolini in Livorno, he probably met Ettore Serra in 1911, with whom he formed a “fraternal domesticity.” In the same period, he published for the publisher R. Giusti a treatise on philosophy, La Metafisica teologica (Theological Metaphysics), a work steeped in deist and anti-traditional speculations. It was through Serra’s influence that Kutufà delved into the paths of aestheticism, approaching the aesthetic theories of Angelo Conti and the thought of Nietzsche, also sharing a deep love for musical giants such as Beethoven, Wagner and Catalani, and a refined taste for the Primitives and Pre-Raphaelites.

Carlo Servolini was among the first to document this extraordinary cultural season, celebrating Kutufà as a “cult poet, man of letters and more,” who remained unjustly condemned to oblivion because, “imitating the ancient so well, he became creator, so that anything but a craftsman he was.” From this intellectual fellowship was born a veritable cenoby, coordinated by Servolini himself, which Gino Mazzanti would evoke in 1968 as a “brotherhood” (G. Mazzanti, Ricordo ventennale di un maestro. Carlo Servolini painter and etcher (1876-1948), in “Le Venezie e L’Italia,” VII, 3, 1968). This group contributed to the germination, in the Livorno of the Caffè Bardi, of a symbolist humus fueled by Ruskinian aesthetics, D’Annunzio aestheticism and the neo-Gothic revival, coordinates that were absolutely unprecedented for the city.

A tangible example of this cultural effervescence is the publication, in 1928, of Àkanthos by Gino Mazzanti, a bibliographic unicum that represents an outpost of the popularization of the Ruskinian word in Labronian soil. The exhibition displays a prophetic illustration of it, embellished with a D’Annunzian quotation from Per l’Italia degli Italiani, Discorso pronunziato in Milano dalla railingera del Palazzo marino on the night of August 3, 1922, later published in “Bottega di Poesia” (Milan 1923).

The exhibition itinerary is the result of a very dense network of bibliographic research and the pioneering documentary cataloguing effort conducted by Stefano Andres in the Grubicy-Benvenuti Fund, kept at the MART (Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art of Trento and Rovereto) Archives. This work has made it possible to devise an itinerary that alternates illustrations, engravings, drawings and pictorial works by Kutufà, all of which are functional in redrawing, through a surprising sequence of comparisons and evocative counterpoints, the highly cultured critical, literary, philosophical and aesthetic temperament that Aleardo Kutufá asserted in perhaps his most inspired and accomplished work: the volume promoted by Ermanno Tallone, Benvenuto Benvenuti, Un colloquio di Aleardo Kutufá d’Atene, published in Lucca by Edizioni A. Lippi in 1944.

Dozens of missives and other documentation concerning Aleardo Kutufá have been found within the Grubicy-Benvenuti Fund. Prominent among them is a greeting card sent by the artist to Vittore Grubicy, presumably in 1915, when he still resided in Piazza Carlo Alberto in Livorno. Even more significant are the more than 50 epistolary testimonies exchanged with Benvenuto Benvenuti between 1911 and 1951, with particular reference to the events of the 1940s, a crucial period of collaboration between the two artists for the drafting of the “Colloquio” later published in 1944. This material not only documents the troubled editorial path of the work, which was complicated by the ongoing war, but, from a philological standpoint, it allows us to appreciate a series of realization projects, working hypotheses, glosses and variants (also regarding the title: L’erede Spirituale Di Vittore Grubicy - L’architettura del Sogno- Benvenuto Benvenuti; Benvenuto Benvenuti Pittore Architetto; Pittori Labronici. Benvenuto Benvenuti. A Colloquium by Aleardo Kutufá of Athens) that were later not included in the final version.

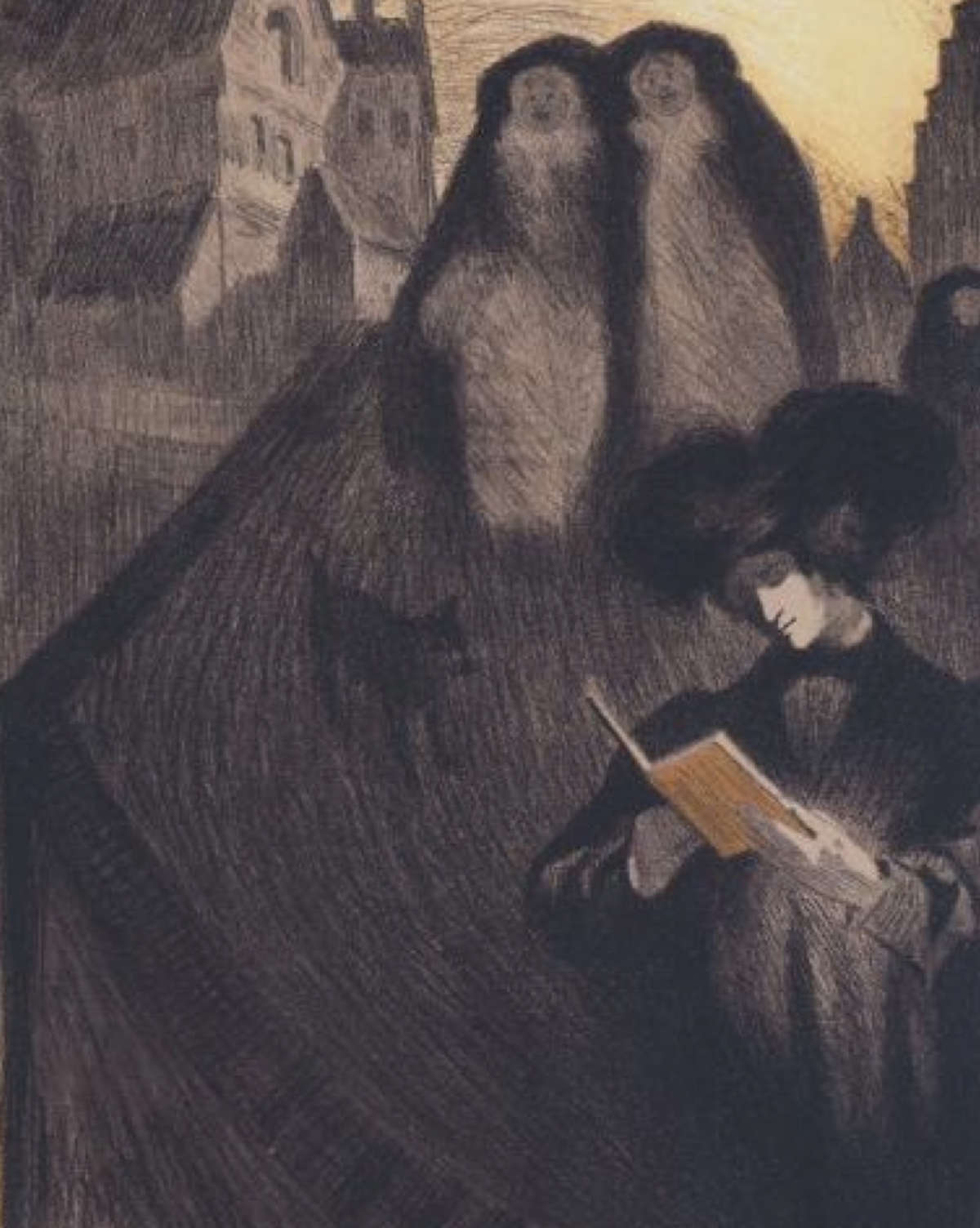

As part of a strategic continuity in the cultural programming of the Pinacoteca Comunale Carlo Servolini, the exhibition continues the dialogue with Raoul Dal Molin Ferenzona, whose admirer and collaborator Aleardo Kutufá was. A sylloge of rare engravings by Dal Molin Ferenzona, courtesy of Emanuele Bardazzi, renews the focus on this protagonist already at the center of the previous exhibition Enchiridion notturno. These works explore themes ascribable to “convent mysteries” shrouded in languid mysticism and religious sensualism, fully in line with the crepuscular poetics matured by the artist in Rome through his frequentation of the literary coterie of his fraternal friend Sergio Corazzini. The engravings belong largely to Ferenzona’s so-called “purist” period, in which, through drypoint and diamond point, he obtained a distilled, subtle and at times evanescent sign to delineate predominantly female monastic figures, pervaded with enigmatic indecipherability, with clear references to the sphinx-like faces of Belgian artist Fernand Khnopff, whose Un voile drypoint is exhibited for comparison.

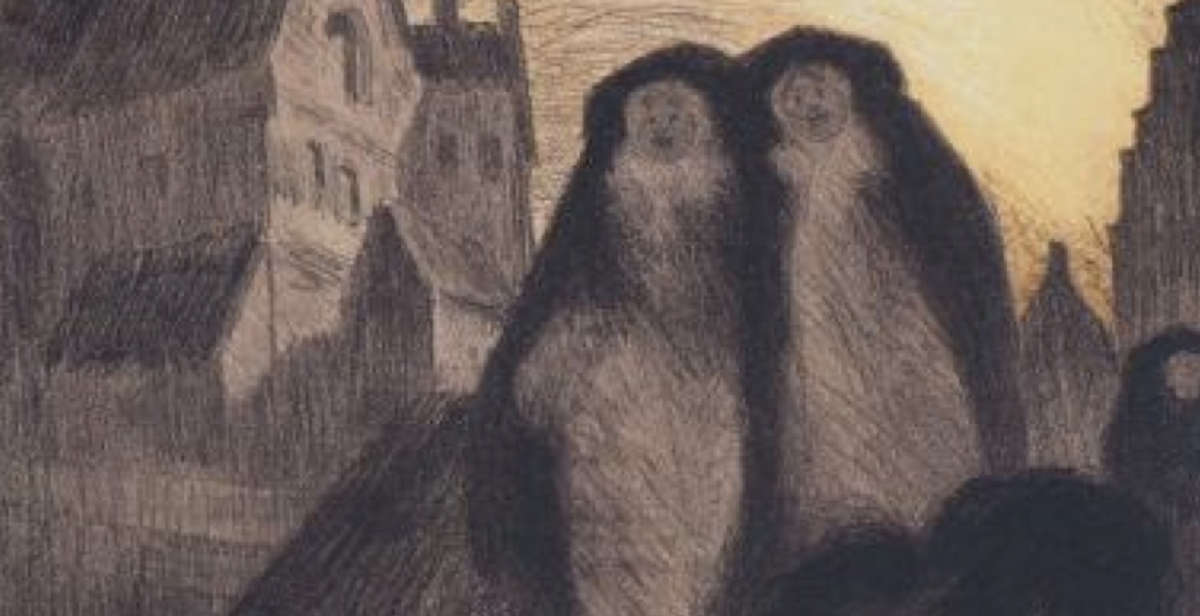

The exhibition also offers an itinerary on that exceptional conjuncture of Roman Crepuscularism, which drank extensively from the poetic literature of Belgian Symbolism, electing the silent melancholy of cloisters and convents as an evocative source of inspiration. An inescapable reference is the novel Bruges-La-Morte by Georges Rodenbach, from which Georges de Feure (pseudonym of Georges Joseph van Sluijters), born in Paris to a Dutch father and a Belgian mother, also drew inspiration in the album Bruges mystique et sensuelle performed in 1899. Two lithographs(La Canal and Le Marché aux puces) of this work are shown along with a similar subject published in Les Maîtres de l’affiche. De Feure captured from the Belgian writer’s books (not only Bruges-La-Morte but also the later novel Le Carillonneur) the double sensual and dreamy soul of Bruges, where mysticism and passionate love were intertwined.

In a singular etching by Bona Ceccherelli, a pupil of the Florentine school of engraving directed by the Umbrian Celestino Celestini, one can still sense, several years later, certain echoes of the Defeurian suite in the procession of beguines toward a surreal church that recalls in turn the geometrically designed architecture of Celestini himself, for a brief period assistant set designer to Edward Gordon Craig at the Goldoni theater in Florence.

Also emblematic is the case of Umberto Prencipe, who in 1905 retreated in complete solitude to Orvieto, finding in the cloistered, deserted and nocturnal atmospheres of the Umbrian town themes of literary emotion that evoked Rodenbach’s “dead city” (the etching Ora triste is on display). There he was joined by his friend Ferenzona, who had visited Bruges in 1906, evoking it in the poem Brugge and later dedicating to it an etching now on display in Collesalvetti. Particularly significant is the presence in the exhibition of Mélanie Germaine Tailleur’s color aquatint, which faithfully reproduces Khnopff’s painting, Souvenir de Bruges. L’entrée du Béguinage, featuring the same framing used by the artist for the title page of Rodenbach’s novel.

Inspired by the poems of Émile Verhaeren, another cult writer among the Roman crepusculars, are a number of lithographs by Constant Montald, Fernand Khnopff, René Janssens, Amedée Lynen and Georges Baltus, executed on the occasion of a conference in honor of the famous man of letters and collected in a special issue of the Belgian magazine “Le Musée du Livre” in 1918. Two subjects belonging to the Symbolist and Rosicrucian season of the French artist Marcel-Lenoir (pseudonym of Jules Oury) depict the phantasmal apparition of a female face sprung from the thoughts of two wise men in monk’s robes in front of a table lit by the flames of a lamp(La Pensée) and, also, a master xylographer resembling an old magician seated on a wooden chair carved with arcane symbols inside a medieval-style workshop, “ciseleur des son rêves avec ses doigts subtils” in front of a block to be carved with burins(Le graveur sur bois, executed for “L’Image,” a magazine of French xylographers in defense of original wood engraving, threatened by modern reproductive techniques).

The exhibition is divided into four thematic sections, each exploring a particular aspect of Kutufà’s research and the cultural context in which he worked.

The first section, titled Poems of Stone: Spiritual and Aesthetic Renaissance in Livorno in the Sign of Ruskin, aims to investigate Aleardo Kutufá’s syncretistic attitude, between Ruskinian predilections, neo-Gothic pastiches and Parnassian-style settings. Opening the exhibition are two icons of Ruskinian iconography, the lithographs St. Mark’s. Details of the Lily Capitals and Ca’ Bernardo Mocenigo. Capital of Window shafts. Paired with these are, with extreme suggestion of comparative intentionality, a number of Gino Mazzanti’s refined, much-quoted illustrations from his major historical-critical work, Àkanthos. A Breviary of Art, with 120 illustrations by the Author, vol. I: Architecture, Raffaello Giusti, Editor-Livorno 1928, dedicated “To Prof. Lorenzo Cecchi, architect.” The “vision of Cecchi’s luminous and fresh watercolors,” made on the occasion of his “peregrinations as an architect-painter” from Rome to Pompeii to the “dead cities” of Magna Graecia and Sicily (some of which are on display in the exhibition), imposed on the Livorno of the Caffè Bardi “veneration for the magnificent and inexorably closed past age.” In compiling the volume, as stated by Mazzanti himself, the intention was to collate excerpts from famous Italian and foreign writers, ancient and modern, to the point that quotations from Gabriele d’Annunzio, Francesco Milizia, Filippo Baldinucci, John Ruskin, Giorgio Vasari, Ugo Ojetti, Jean-François Champollion, Goethe, and Maspero are interwoven ex aequo in 438 pages. It was precisely Aleardo Kutufá, with his unpublished Triptych, who sanctioned in Livorno a season crowned by Ruskin’s aesthetics, intermingled with Orientalisms and Gothicisms, whose syncretistic mixture came to engulf even the esoteric temperament inherent in the architectural visions warped by Benvenuto Benvenuti, who evoked in his mind Ruskin’s sentence that “the architect must not look at a project in the skeleton of its lines, but conceive it when it will be illuminated by sunrise or abandoned by sunset.”

The second section, entitled Artistic Polyphonies: Lauds of Heaven, Sea and Earth, in line with the arguments profiled by Aleardo Kutufá in his volume Benvenuto Benvenuti. A Colloquium of Aleardo Kutufá of Athens, directs attention from the esoteric architectures of the Livorno Divisionist to the so-called “glory of Creation,” distinguished by the symbols of the Seasons and the allegories of the Ages of Existence, orchestrated by a music of that “gigantic organ,” functional to the diffusion of a vertigo of immensity, of an unexpressed dream bent on transfusing into seven symphonies the themes of Benvenutian painting, namely “the symphonies of reality, pantheism, mysticism, primordial voices, tragic mystery, dreams, and death.” Thus resurfaces the cultural patronage of Angelo Conti, who invested Benvenuti with ideals consonant with his theoretical reflection, according to which “a vision of the Orient” shone in Benvenuti’s architecture, in line with the essence of so many Tuscan architectural testimonies, which, from the Florentine Baptistery to the interior of Siena Cathedral, managed to convey “a rhythm of oriental songs.” The result is that sort of glad tidings announced by Kutufà, which is “the hour of the lamps,” a formula allusive to the title of Francesco Casnati ’s (Szombathely, 1892 - Como, 1970) article, “The Hour of the Lamps: a proposito del Notturno di d’Annunzio,” which appeared in the magazine “Vita e Pensiero” in 1922, where the journalist restores the exceptional genesis of the so-called “commentary of darkness”: in other words, it is d’Annunzio who, “in the midst of the torment of visions,” announces yet another metamorphosis of a soul, now risen to “pure spirit on top of the ideality of the world.” They are therefore “shadow explorations” those appreciated by Casnati and evoked by Kutufà, reverberating a new D’Annunzio style, equivalent to “usual rhythms” that evoke “music of a most tenuous species.” Among the icons in that section are dominated by Raoul Dal Molin Ferenzona’s La Porticina (courtesy Emanuele Bardazzi), Fountain in the Villa by Carlo Servolini (Municipality of Collesalvetti), The Garden of Light, 1925 by Benvenuto Benvenuti (private collection); Evening, 1921 by Gino Romiti (courtesy Gianni Schiavon), and finally two monumental drawing testimonies of the so-called “Virgilian” and “Theocritean” landscape art, by Benvenuto Benvenuti, Vicolo con case and Paesaggio (courtesy Galleria d’Arte Goldoni, Livorno), where the eternal and emblematic alternation between sun and shadow repeats the mysterious enchantment of the polarities of the existential cycle.

The third section, titled Gli Uffizi del Vespro: Città d’incantesimo e di sogno (The Uffizi of the Vespers: Cities of Enchantment and Dream), offers a poignant itinerary among certain crepuscular visions of Divisionist vocation and D’Annunzian gestation, warped by Aleardo Kutufá in his Elegia delle città morte. Poem and Pictures of Aleardo Kutufá of Athens (Livorno, Benvenuti and Cavaciocchi 1928). These works are compared with seductive crepuscular attestations by Lorenzo Cecchi, Carlo Servolini, Benvenuto Benvenuti, Renato Natali, and Raoul Dal Molin Ferenzona, and at the same time with some magnificent examples of international symbolism, particularly Belgian. Inaugurating the section is Lorenzo Cecchi’s Abandoned Convent, head of the school of many Labronian artists, from Benvenuto Benvenuti to Renato Natali, but above all coordinator of the fraternity that also included Carlo Servolini and Gino Mazzanti, whose silent architecture, poised between neo-medieval legends and conventual mysteries, relaunched neo-Gothic aesthetics in the Leghorn area with original stylistic features. A fascinating nucleus of engravings by Raoul Dal Molin Ferenzona, intent on transcribing the enchantment of “dead cities” of D’Annunzian echo in nocturnes pervaded with melancholic ecstasies and visionary ardor, constitutes its physiological epilogue. If Renato Natali’s La Chiesa della Valle Benedetta, 1920-1922 (courtesy Galleria Corsini, Castiglioncello), leads the enchantments of the vesper back to a register of expressive drama offset by Labronian folklore, the visionary ascensionality of the towers of San Gimignano immortalized in Irma Pavone Grotta’s woodcut, City of Dreams (1926), recite almost literally the spiritual tension vibrant in those cities shrouded in mysterious enchantments, evoked in the poems of Aleardo Kutufá.

The fourth section, titled Nei penetrali del mio Tempio: il cenobio degli Eletti tra misteri conventuali e formule iniziatiche (In the Penetrals of My Temple: the Cenobio of the Elect between Conventual Mysteries and Initiatic Formulas), intends to unravel the mystery of the conventual theme and the allegory of a fantastic Middle Ages, vague by Aleardo Kutufá, in symbiosis with some cerebral mystical visions signed by Raoul Dal Molin Ferenzona between the 1910s and 1930s. Prominent among these are The Sacrifice, 1909 (drypoint); Convent Under the Snow, 1910 (drypoint); The Mystery of the Eucharist, 1910 (drypoint); A Sin (drypoint); Bruges, 1914 (etching); The Bad Nun, 1915 (etching and drypoint); and The Face of the Communicant, 1932 (drypoint). These works are to be considered a true celebratory hymn to the convent mysteries shared by the Tuscan artist with some protagonists of European symbolism. Indeed, this section is embellished by numerous attestations of cloistered settings, signed by the protagonists of the Belgian Symbolist strand, of which splendid engraving specimens appear in the exhibition, particularly by Constant Montald (Belgium 1862 - 1944), Fernand Khnopff (Grembergen-lez-Termonde, 1858 - Brussels, 1921), René Janssens (Belgium, 1870 - 1936), Amedée Lynen (Saint-Josse-ten-Noode, 1852-Brussels, 1938), Georges Baltus (Courtrai, 1874 - Overijse, 1967); Georges de Feure (Paris, 1868 -1943), taken from Le Cloître by Emile Verhaeren (Sint-Amands, 1855 - Rouen, 1916), a poet who rose to be the progenitor of the Belgian Symbolist school. Among the unexpected surprises in this section are several engraving masterpieces by Charles Doudelet.

The exhibition will be on view at the Carlo Servolini Municipal Art Gallery (Villa Carmignani Complex, Collesalvetti, Via Garibaldi, 79 / Poggio Pallone location) with free admission every Thursday from 3:30 to 6:30 pm. Reservations for small groups are also possible. The first special opening is scheduled for Sunday, April 27, from 3:30 to 6:30 p.m. For more information you can contact 0586 980227 - 3926025703, send an e-mail to pinacoteca@comune.collesalvetti.li.it or visit www.comune.collesalvetti.li.it.

|

| An exhibition rediscovers Aleardo Kutufà: a journey through symbolism and dreams of the Middle Ages |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.