What deep bond unites an island with its simulacra? And how did 20th-century masters traveling between the Mediterranean and the South Seas absorb and interpret that bond? The exhibition ISLANDS AND IDOLS, which inaugurates the summer season of the MAN Museum in Nuoro, was created to answer these questions and to understand how the symbolic and mythical power of archaic figures, guarded within the confines of insularity, was regenerated, centuries later, in the forms of the modern.

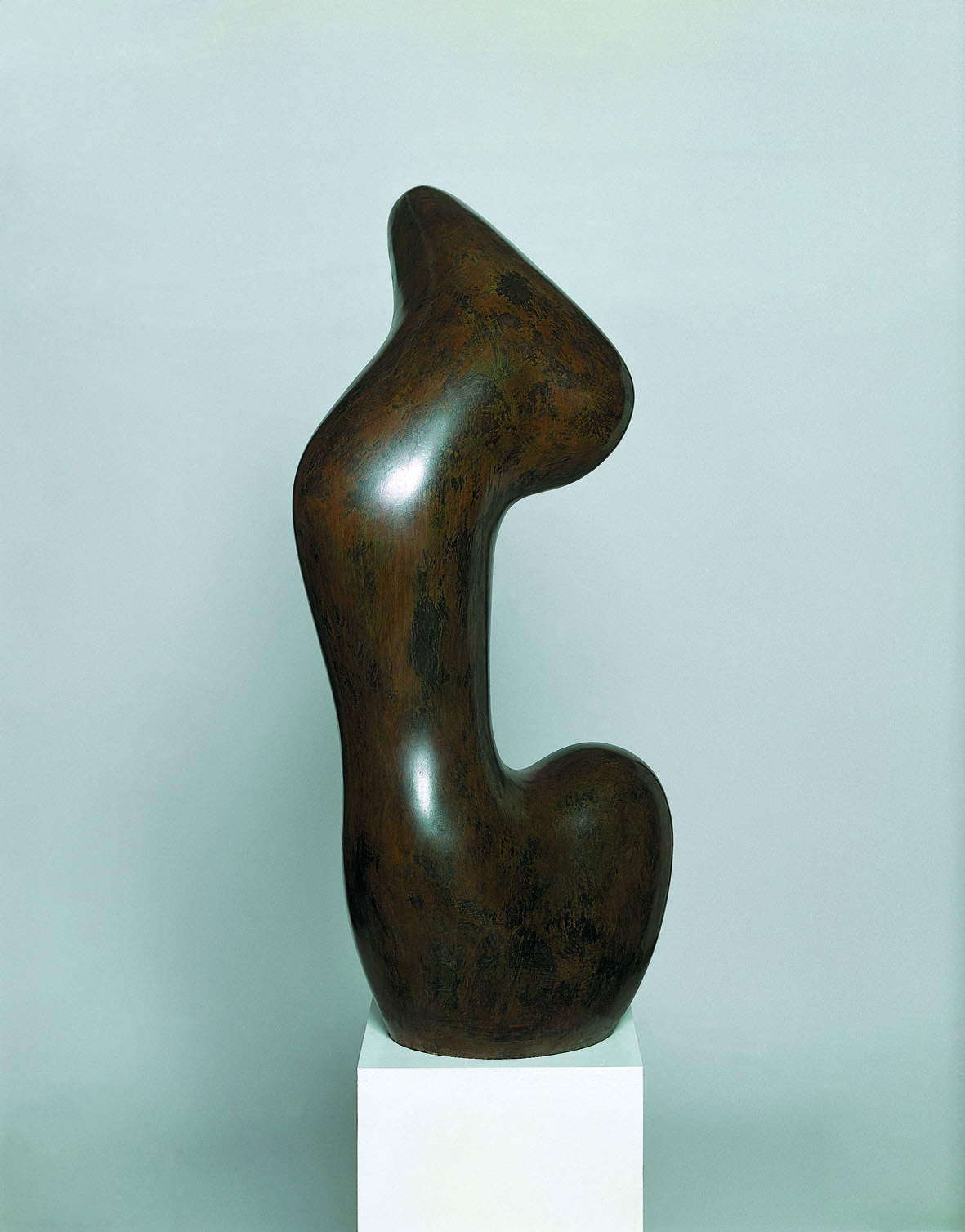

Hovering between the Neolithic and the dawn of the twentieth century, between archaeology and the avant-garde, between Cycladic idols and the wooden sculptures Gauguin carved in his Tahitian years, the path fluctuates between past and present in search of returns, shared sentiments, genetic inheritances, effusive drives destined to resurface in alternating phases, as in geological cycles, and to guide the hands of the authors intent on shaping related forms. Not, then, the idea of the traveler who, exploring, finds, absorbs and replicates. But the concept, more vital, that the ancient and the modern touch each other outside of time and space, strongly nurtured by the same need: to represent the elsewhere through statues, steles, monoliths that personify the invisible on earth.

“There is no need,” Chiara Gatti writes in her text, "for postcolonial revisionism to assert that, in their hieratic stature, there is nothing primitive, exotic, disturbing. It is pure abstraction. They are mother goddesses, pitiful and grand at the same time, like Egyptian prefics, like Etruscan offerings, like handmaids stolen from Greek vascular painting. And their gazes peering into the void, immersed in a Casorati-like expectation, recall the disarmed immobility of Dürer’s Melencolia, an allegory of the human intellect pondering the fate of the cosmos."

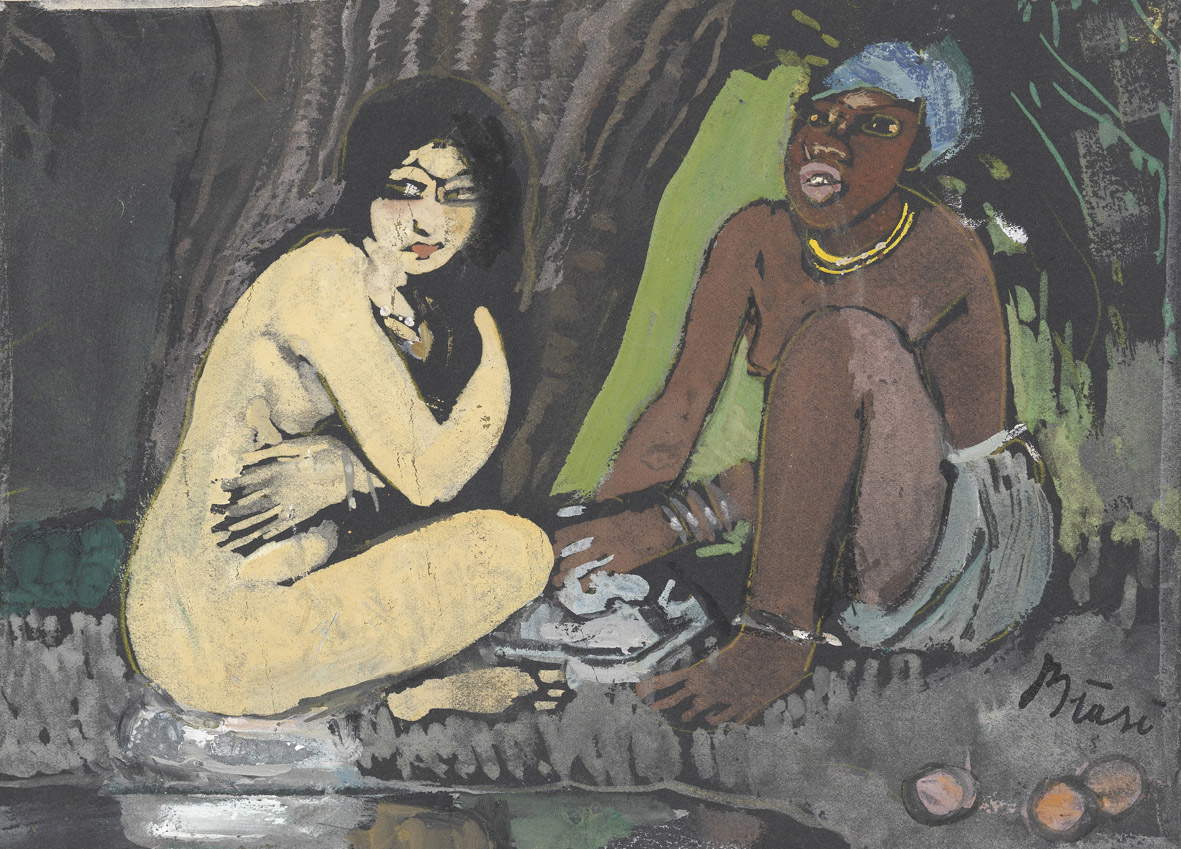

Critically posing itself as a reflection on today’s concepts of otherness, primitivism and their fallout in the heart of the postcolonial debate-extended far beyond art history-the exhibition sinks inside anthropological reasons inherent in the presence of totemic figures in the circumscribed perimeters of an’island and explains how masters of the caliber of Gauguin, Pechstein, Miró, Arp or Matisse, in the course of their travels, reworked such coexistence, projecting their own statuary icons into the absolute dimension of the sacred.

Beginning with Gauguin’s first “escape” to Brittany in 1886, according to a concept of the island as an ideal place, immune from the drifts of the civilized world, the path narrates theexperience of Jean Arp, who collected Cycladic statuettes, ensnared by their magnetism concentrated in a fist, and of Max Pechstein who landed in 1914 in the Palau archipelago, where he lived in contact with local communities on theisland of Angaur and portrayed there solemn male faces as gods. “I saw the sculpted idols in which a trembling piety and reverential awe before the inscrutable power of nature had imprinted hope, fear and awe, before their inescapable fate.” Joan Miró, in his daily notes, evoked the Moai statues of Easter Island as a powerful reference for new sculptural forms, recognizing in them the embodiment of an ancestral spirit. And again, Alberto Giacometti, who had found his own island among the erratic boulders of Maloja, made of each of his portraits an idol, a guardian of the temple, kneeling before the immaterial.

Writes Matteo Meschiari in his catalog text, “The point is to try to understand not so much the sociology, philosophy and geopolitics of being and experiencing the island, but how the Earth-Sea geomorphology contains within itself fossils of mythical thought, how the encounter between rock and water is a kind of morphogenetic field capable of generating myth. Island-related conceptual stereotypes are an obscuring filter: Exclusion, separateness, loneliness, shipwreck, castling, prison, exile, confinement, are only the most prevalent, but as soon as we move to Ocean-centered cultures such as the Viking or the Polynesian, we realize that theWest is entangled in a geocentric colonial paradigm that always prioritizes land, a continental gaze that perpetuates a hegemonic geographic model where the sea is the void. For those who live at sea, on the contrary, water is the center of the world, its maps indicate submerged landscapes and motions of currents, while islands, especially oceanic ones, are small pauses, zones of suspension in the salty immensity, and the archipelago is a pitted hyperobject held together by the dynamism of the waters, by the fullness of the sea.”

A selection of more than 70 works counts archaeological finds arriving from Sardinia’s major archaeological museums, the Menhir Museum in Laconi and the Museums of Brittany, as well as an exceptional loan from the Department of Greek, Etruscan and Roman Antiquities of the Musée du Louvre in Paris. Alongside these, works by the modern masters come from major European collections, including the National Gallery Prague (for Gauguin’s wooden sculptures), the Gallery of Modern Art in Milan, the Musée départemental Maurice Denis, the City Museum of Locarno, Fondation Giacometti and Archives Henri Matisse, joined byArchives Florence Henri and private Italian collections such as Diffusione Italia International Group srl and Enrico Sesana’s print collection.

Finally, a lunge dedicated to prehistoric Sardinia offers an in-depth look at the world of the idol in Sardinian land, articulated around four main thematic cores: the bull (a male symbol associated with the cult of power and fertility), the Mother Goddess (a female figure linked to birth and the continuity of life), the “upside down” (a representation of the afterlife and ritual reversal), and anthropomorphic menhir statues, real idols carved in stone and destined to dominate the landscape as eternal presences.

The installation, curated by architect Giovanni Maria Filindeu, organizes the set of works on display in a spatial form that recalls the configuration of an archipelago formed by small thematic groupings. Guiding the articulation of the elements, both wall and floor, are the intentional and critical use of color and the choice of materials. In particular, celenit (an aggregate of wood fibers and cement) used for the display bases, as well as the use of washed sand, a natural and evocative binder whose icy tones marry the summer palette of textures that draw metaphysical maps.

For all information, you can visit the official website of the Man of Nuoro.

|

| Nuoro, the link between islands and their simulacra in an exhibition at MAN |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.