History and the present, for women are something to be rewritten again and again. Especially today, because of the complexity of the world in which we live and operate. Rewriting and making History with one’s own name, HERSTORY and not HISTORY, means questioning and confronting even from words, linguistic issues, and themes that fall within the orbit of public and private dimensions, real places of inquiry. This questioning of issues and words, of images and visual representation, in our case, is accomplished through artistic language, which, more transversal than other modes of expression, presupposes an in-depth investigation precisely because it does not belong exclusively to gender studies or feminist militancy. That is why it is necessary to ask what we are talking about when we say women’s art. Does it exist and does it make sense to talk about specifically feminine or feminist art?

These are questions that start very far back and have their origin in the feminist movement of the 1970s. Feminism was, and still is, a militant revolutionary and nonviolent organization that, in that historical period, represented not only a new social and cultural phenomenon but, above all, the starting point and then the trigger for profound changes in legislation and customs. But are those assumptions still valid today? Are there still points of tangency with reality and the post-contemporary art scene? A vexata quaestio currently much debated, but in what terms should it be redefined? We asked Paola Ugolini, an art critic who specializes in gender studies related to art experiences, who will also talk to us about the exhibition, which she curated with Cecilia Canziani and Lara Conte, Io dico Io /I say I, currently underway at the National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art in Rome.

How urgent the “feminine” issue still is and how present it is in the contemporary art scene is confirmed by numerous exhibitions and publications, but how much we still need to build a careful narrative on the topic is shown by two seemingly trivial, and diametrically opposed, episodes. The first is the one related to the preference to be called director by dorchestra director Beatrice Venezi at the Sanremo Festival, and the second is the photo, which went viral on social media, of Afghan schoolgirls filmed while taking their university entrance exams.

|

| Afghanistan, July 2020, female students waiting to take university entrance exams. |

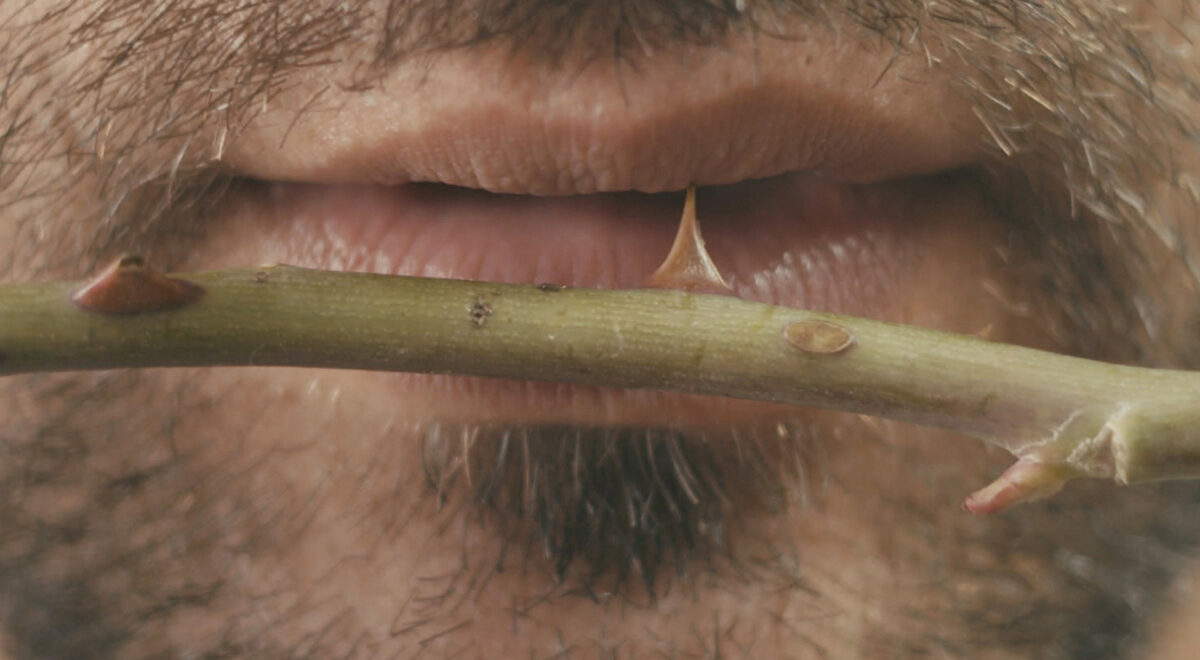

ADFS. We start with a gesture. Plucking a rose, from the work of Silvia Giambrone (Agrigento, 1978) featured in the Mascarilla 19 project (in my opinion outstanding) curated and produced by you and Beatrice Bulgari.

PU. The gesture you are referring to is one of the actions that the actor in Domestication, the short film produced by the InBetweenArtFilm Foundation for Mascarilla 19, performs at the beginning of the film as he sits at a kitchen table taking a yellow rose from a vase and beginning to remove the thorns from the stem with his teeth, then placing the thorns lined up in order on the table top. Mascarilla 19 is the title of the project that was born exactly one year ago, during the first lockdown, from an intuition of Beatrice Bulgari, president of the Foundation, who had been struck by an article she read in a foreign newspaper about how Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez had devised with the Ministry of Equal Opportunity a protocol to help women victims of domestic violence who could walk into any pharmacy in the country, one of the few open businesses, using a code word, mascarilla 19, to ask for help. The idea that arose because of restrictions to contain the pandemic, whereby so many women were and still are forced to cohabit coercively with their perpetrators, was linput to try to address this scabrous topic with the cross-cutting language of contemporary art and specifically moving images. The project was curated by Alessandro Rabottini, artistic director of the Foundation with Leonardo Bigazzi and myself. The eight short films, made by as many artists, both Italian and international, told the tragedy of gender violence from very different angles. Silvia Giambrone, for example, wanted to represent the domestication to it and how, in a toxic relationship, labuso becomes normalized by no longer being perceived as such.

What is the weight of that gesture of uprooting the thorns from the roses? The same roses that, I suppose, are a gift from a man to a woman, in the scene of cohabitation and domestic violence, Giambrone’s specific inquiry

That gesture is obviously a metaphor for violence but also for pleasure and pain. The man and the woman acting within the domestic environment chosen by Silvia Giambrone never meet and are probably each the memory of the other or vice versa, they are imagined and archetypal presences. The actions they perform, even trivial ones like looking in the mirror or washing their faces, are saturated with the violence that has now become so deeply embedded in their relationship that it is experienced as a condition of normality.

Let us continue with a reflection from the commentary, written on March 6, by the artist Francesca Merz, following the outpouring of discussions that arose after the intervention of journalist Barbara Palombelli and after the statement of dorchestra director Beatrice Venezi during the fourth evening of the San Remo Festival. None of us, feminists, live outside of society, Merz wrote, and none of us, feminists, however rabidly convinced of our own superiority over others, live our choices and our lives without being deeply conditioned by huge social and patriarchal patterns, the difference, in my opinion, is simply self-awareness, that is, realizing how entangled we ourselves are in this method of self-judgment.

We women are daughters of patriarchy and all of us, more or less consciously, are imbued with it, and this is something we have to deal with all the time. As Simone de Beauvoir wrote in her illuminating 1949 essay, Le deuxième Sexe, women are not born, they become. Only by studying and becoming aware of our female sexuality, thus not missing men but different subjects, could we truly make a radical impact within society, to pulverize pre-established patterns and make a breakthrough. Feminist philosophies are many it is true, but the basic kernel is one: equality and equal treatment in terms of rights, career opportunities and social representation. I, personally, find it quite ridiculous that a woman feels so diminished in her being a woman, that is, a sexed subject in the feminine, that she feels it more authoritative to be defined in her profession in the masculine. We must never forget that feminism is also in words and not only in street actions or claims. Sociolinguist Vera Gheno in the essay Feminine Singulars writes it happens that what is not named tends to be less visible in people’s eyes. In this sense, naming women who do a certain job with a feminine noun is not a mere whim but an acknowledgement of their existence: from truck driver to coal miner, saleswoman to branch manager, auditor to judge, gardener to mayor. And patience if the words sound bad to some: you can get used to it. Litalian is a masculine sexualized language, so to start declining professions into the feminine is for me not only linguistically correct but also a political, militant stance. To deem cacophonous words such as architect, minister, lawyer, mayor is a legacy of an irredeemably masculinist mentality; a redetermination of the feminine must also be thought of starting with words and their conscious use. Renaming professions to the feminine is a necessary practice to actively act feminism.

|

| Silvia Giambrone, a frame from Domestication (2020) |

|

| Silvia Giambrone |

In your opinion, does the lack of sensitivity to linguistic sexism and an attention to women’s gender issues (not only linguistic) depend on one’s biography, i.e., how much can a more or less ingrained and introjected patriarchal mentality affect a woman’s and an artist’s career, sentimental and professional life?

The lack of sensitivity to gender issues is the consequence of a cultural vacuum, of specific training; the media for that matter do nothing but paint feminists as ugly, hairy, man-hating witch-women. This word, therefore, is still frightening to all those women and even men who, out of ignorance, have not gone through personal growth and gender studies. In the West today, the patriarchal mentality is receiving major shocks but, unfortunately, we still live in a misogynistic world in which the rights of minorities, migrants, women, belonging to the GLBTI community, seem only graciously granted and in any case always ready to be revoked at the first sign of crisis. The pandemic has blatantly shown that equal rights have not been achieved, women are in fact suffering a great deal of discrimination in terms of employment since society (which is based on the unwritten rules of patriarchy) believes that they are the ones who have to sacrifice salary and career to take care of family management. We live in a country that in the 1970s produced a very vital feminism on both a theoretical and practical level but which, with the arrival of commercial television, has been buried by a disturbing exploitation of the image of women, in which their value is measured solely by the most basic criteria: their bodies, their outward appearance, and the lability of being subordinate to men. Even today, we still experience a profound contradiction between real woman and the consumerist production of the ideal woman homologated by Mediaset and Rai networks, all of which generates confusion and increases the resilience of gender stereotypes.

In August, while there was talk in Italy about the increase in cases of domestic violence (the region where the number is highest is Calabria) which is why the Mascarilla 19 project has found fertile ground, the photo of Afghan women who under the sun and despite the risks, were taking the admission test to enter the University went around the world how much distance is there in Italy from that image?

Currently huge to tell the truth but the distances can always shorten if women and even men do not begin to become aware of their diversity and realize that collaboration and mutuality are the only sensible answer to ensure the future of our species.

These days, I am reading French writer Pauline Harmange’s pamphlet, I Hate Men. I think her strong position, which risked being censored for inciting gender hatred, is nonetheless important to consider, what do you think?

That pamphet is very intelligent and its title so strong and assertive necessary to shake consciences. Pauline Harmange’s statements are quite revolutionary but also definitely sensible like when she writes that women are encouraged by society, literature and everything else to love men, but we should definitely have the right not to. That said, every field of knowledge must be investigated from a nonhegemonic point of view, repositioning the female presence is a necessary step in order to be able to reread history in a non-situated way.

|

| Carol Rama, Appassionata (1943; Turin, private collection). Photo by Pino DellAquila © Archivio Carol Rama, Turin |

|

| Ketty La Rocca, With Attention (1971; The Ketty La Rocca Estate) |

|

| Silvia Giambrone, The Damage (2018). Courtesy the artist & Studio Stefania Miscetti. Photo by Giordano Bufo |

|

| Monica Bonvicini, Fleurs du Mal (pink ) (2019). Courtesy lartist & Galleria Raffaella Cortese, Milan © Monica Bonvicini & VG Bild Kunst. Photo Alessandro Garofalo |

There is one other point I would like to make with you before we get to the current exhibition at the National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art in Rome... There are many exhibitions, publications and events, related to the issue of gender studies. Exhibitions such as Maria Angeles Vila Tortosa’s Hysteria, Soggetto Imprevisto, and Who Am I? just to name a few, have marked a valuable moment in the journey of female knowledge and visual repertoire.

These exhibitions are all important. I have curated several exhibitions repositioning the presence of women artists (including Hysteria de Secretis Naturae) and I welcome these kinds of exhibition projects every time, as I said before, it is important to be able to create a different narrative, and the exhibitions you mentioned are important intellectual exercises in rewriting from a non-hegemonic point of view the history of art of the last fifty to sixty years.

Let us come to the Roman exhibition, I Say. The areas where, in my opinion, the legacy of a secular patriarchy is most pronounced are those dealing with Presence, the body/sex dimension, language, and speech taking. By Presence I mean the physical and real places where the presence of women is precluded or limited, and they are, as is known manifold, the high offices in politics, for example by the lapping of Language we speak of linguistic sexism, that is, linguistic subjugation to the use of the neuter masculine. Clearly, the issue related to Sex and the use of the Body is lambito where most macho bullying is exercised" and that more than the other aspects pertains to artistic lambito, with the developments of Body Art, for example. What remains is the Taking of the Word, an area that starting with Carla Lonzi, continuing with Tomaso Binga, (aka Bianca Pucciarelli Menna) up to the exhibition Io dico io, highlights how women have, again, inherited counterproductive habits, because it emerges how it is always the man over time who has most exercised the taking of the word. For this reason, the Io dico io exhibition is of particular importance. Tell us why.

Io dico Io/I say I is the assertive statement by which women become aware of themselves and their uniqueness, specifically Io Dico Io is the principle of the essay La presenza delluomo nel femminismo, written by feminist philosopher Carla Lonzi (1931-1982) in 1971. The occasion for the realization of this transgenerational and polyphonic group show of only Italian women artists, which I curated at the invitation of Cristiana Collu with Cecilia Canziani and Lara Conte, and which is currently set up in the spaces of the National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art, was the donation of Carla Lonzi’s archives to the Museum by her son Gian Battista Lena (the archival material is on display on the second floor of the museum and can be consulted on the website online). This title recounts the female will to take the floor without waiting for it to be granted to her; it is the revolutionary affirmation by which woman becomes the master of her own ability to think, that is, of speech as a creative force. In the beginning was the Word(lógos), the Word was with God and the Word was God recites the first verse of John’s gospel thus establishing that the word is divine and incarnate. But it must be remembered that it was incarnated through the yes of a woman who therefore brought it into the world, even for men. With time and forgetfulness, public speaking and the art of oratory became male prerogatives while chatter and gossip were confined to the home or the marketplace, among women. In antiquity women’s voices were not to be heard in public because oratory was one of the defining characteristics of masculinity as a political gender [ed. note: the goddess Tacita Muta was to be worshipped]. Mary Beard in her essay Women and Power writes that: In the tradition of Western literature, the earliest known example of a man publicly taking away a woman’s speech; telling her that her voice must not be heard in public is at the beginning of Homer’s Odyssey, some 3,000 years ago... It all begins in the first book of the poem when Penelope descends from her private rooms into the great hall of the palace, where she finds a bard entertaining her suitors by singing about the difficulties the Greek heroes were finding in returning home. She is not amused and, in front of everyone, asks him to play something more cheerful. At this point young Telemachus intervenes, saying Mother, go back upstairs to your apartments, and go back to your work at the loom...talking is men’s business, all men’s, and mine above all; for mine is the power in this palace. And she went back upstairs. (Mary Beard, Women & Power. A manifesto. Profile Books LTD, London 2008, pp. 3-4). From Greek mythology to the present day certainly things have changed a great deal and women’s voices have undoubtedly been heard but always at the cost of enormous difficulties and struggles, especially when we consider that our Western culture has continually undervalued women. All too often, women’s voices are silenced because the socially welcome woman is a silent, non-oppositional and welcoming woman, so much so that female representation in the Italian media is largely that reserved for a beautiful, smiling, mute creature. Taking the floor and making one’s voice heard is what Carla Lonzi did who, in addition to being a brilliant art critic, from 1970 with the founding of Rivolta Femminile, the first Italian separatist collective, began to critically define the new feminist subjectivity and to give voice and depth to that unforeseen subject, the woman who has become self-aware, who so powerfully and suddenly bursts onto the public-political scene that is still today, as you point out in your question, is still largely a male preserve. Larte of course has never been feminist or non-feminist but it is undeniable that many women artists have incorporated this revolutionary thought into their work as evidenced by the countless experiments made by women artists from the mid-1960s to the present. Io Dico Io stages as in a grand visual representation the investigation of the gaze and self-representation as a questioning of roles; writing as the practice and narrative of the self; the body as measure, limit, trespass; preciousness as resistance to homologation in order to overturn points of view, de-hegemonize narratives and suggest new postures. I Say I is an open inquiry into the present born of the need to take the floor to affirm one’s uniqueness outside of a legitimizing gaze, beyond stereotypes and impositions to create a space of encounter and recognition, discovering one’s different origins and identities. The exhibition, which opened last March 1, was only open for a fortnight, the museums are closed at the moment, so I hope it will be possible to visit again soon.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.