The new National Archaeological Museum of Luni was inaugurated on May 29, 2025, in the presence of local authorities and representatives of the Ministry of Culture, the entity that manages the vast heritage of the ancient Roman colony of Luna.

A clear day, almost blessed by the gods, the ancients would have said, was the setting for the presentation of a project taking shape from years of reflection and in the choral commitment of numerous professionals. The new exhibit, signed by the firm GTRF, Giovanni Tortelli Roberto Frassoni Architetti Associati, was built inside the Casale Benettini Gropallo, with a scientific project by Antonella Traverso and Marcella Mancusi. The museum and archaeological park are now among the most relevant places for knowledge of the Romanization of the Italian peninsula and Ligurian archaeology.

“Finally, after numerous interventions that involved demolishing the old museum and moving the collections, the new layout is inaugurated today,” says Antonella Traverso, Director of the Museum of Luni, recalling that the new museum, “enriches the offer to the public, extending the exhibition narrative from Luna to Luni, through the 1400-year history of the city.”

“It has been a long journey, the one that led to completely rethink the location of the National Archaeological Museum of Luni,” recalls Alessandra Guerrini, head of the Regional Directorate National Museums Liguria, “today a modern museum opens to the public, which we wanted to set up in an ancient eighteenth-century farmhouse, perfectly inserted in the landscape. The decision not to build a new building is part of the great attention there is today for the archaeological site: a team effort carried out by the Ministry of Culture’s technicians with their different skills. We are therefore particularly happy to be able to welcome the public to a museum dedicated to the ancient Roman city of Luna but also to the history of the area understood over a broader chronological span, starting from Prehistory and ending with the Middle Ages. The path then also delves into the theme of the extraction of the precious Luna marble, now known as Carrara marble, and becomes a starting point to immerse oneself in the extraordinary archaeological landscape that surrounds us.”

“We are in an extraordinary place,” adds the prefect of La Spezia, “where ancient traces are rediscovered and a precious piece is added to this magnificent region. A piece made of culture, tourism and memory of origins, a historical heritage that for centuries has characterized these territories and whose heirs we are today. Heirs who have the responsibility to represent it worthily. Italy possesses an immense and priceless historical heritage. It is up to us to preserve it, make it known, bring it to light when necessary, and spread it around the world. Many of our current merits derive from the past: it is not to our credit that the UNI, the Colosseum, the Pantheon or Milan Cathedral exist. But we have a duty to be conscious heirs to it and to pass on what we have received to future generations. So that, two thousand years from now, our descendants can feel the same excitement that we experience today in enjoying such beauty. When I am in a historical place, I seem to hear the voices of those who have gone before us: as if there is a collective memory that continues to live, to speak, and that, in some way, accompanies our steps.”

Founded to control the people of the area, the colony of Luna found itself in the right place at the right time. Thanks to marble, it gained structural economic importance, which transformed the town from a border suburb to a major production center.

Luni marble, called lunense marble, was in such demand that there were magistrates in Rome and Ostia in charge of controlling its quality. This encouraged its spread until at least the second century AD. Later, Lunense marble was gradually replaced by Proconnesio, the marble from the Sea of Marmara. In the Middle Ages mining fell into crisis, but the quarries were reopened to build the great Tuscan churches.

A particular anecdote is the one about Dante: in 1304, during his exile to the Malaspina family, the poet was in the lands of Lunigiana. It is plausible that he crossed the fields near Luna and, on that very occasion, observing the ruins on the horizon, composed the verses of Paradise in which the memory of the ancient city resurfaces.

Archaeological research in the modern sense began in the 19th century, with the first explorations in 1837: interest grew rapidly and involved scholars and collectors, until it reached the Savoy court: King Charles Albert commissioned the architect Carlo Promis to carry out surveys and excavations. Throughout the next century, finds enriched museums and collections, but it was not until 1964 that the state initiated more structured protection with the construction of the first museum in the archaeological area. Today, after the demolition of the old building for seismic reasons, the new museum finds a home in the Casale Benettini Gropallo, harmoniously integrated into the archaeological park.

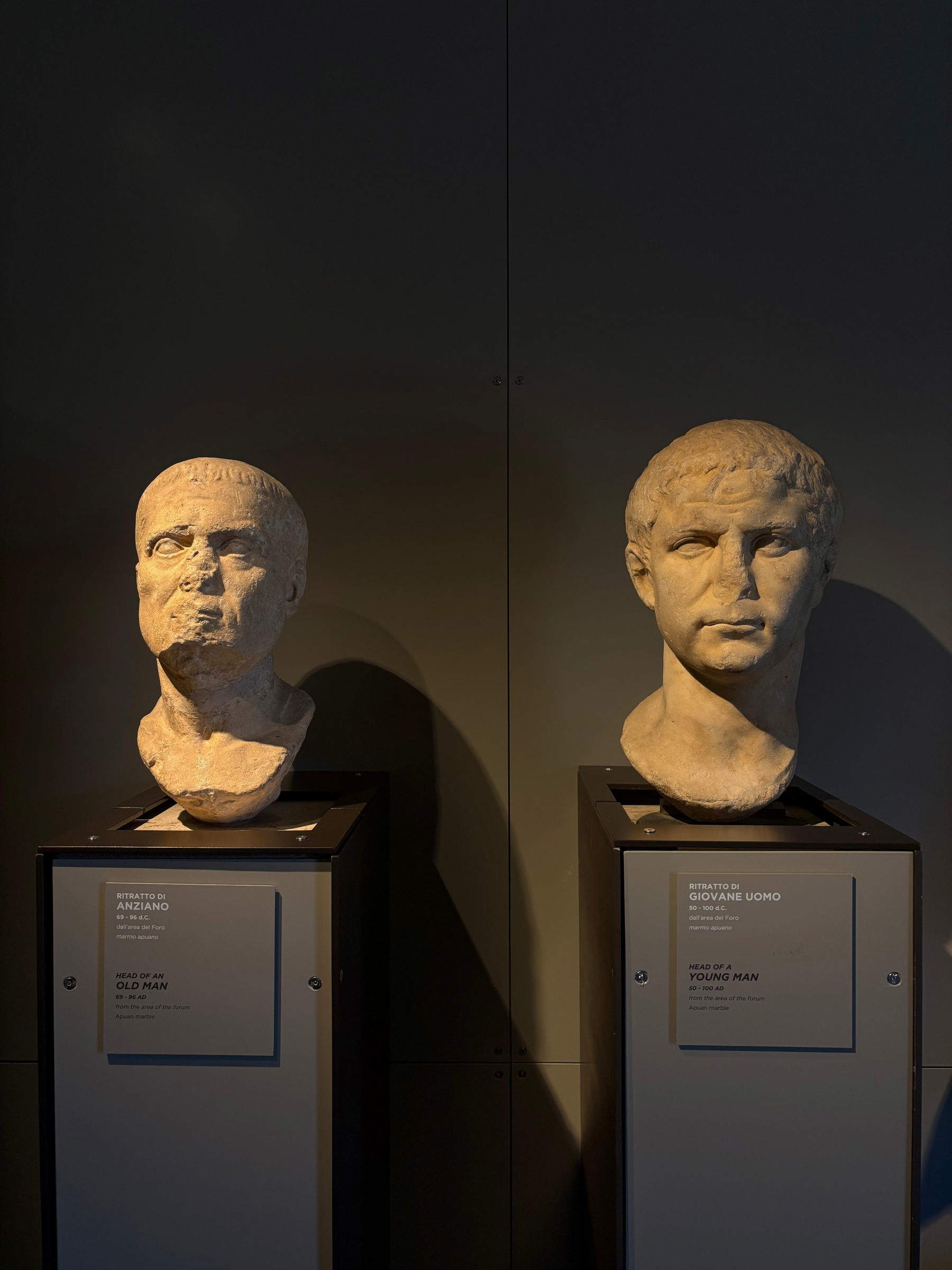

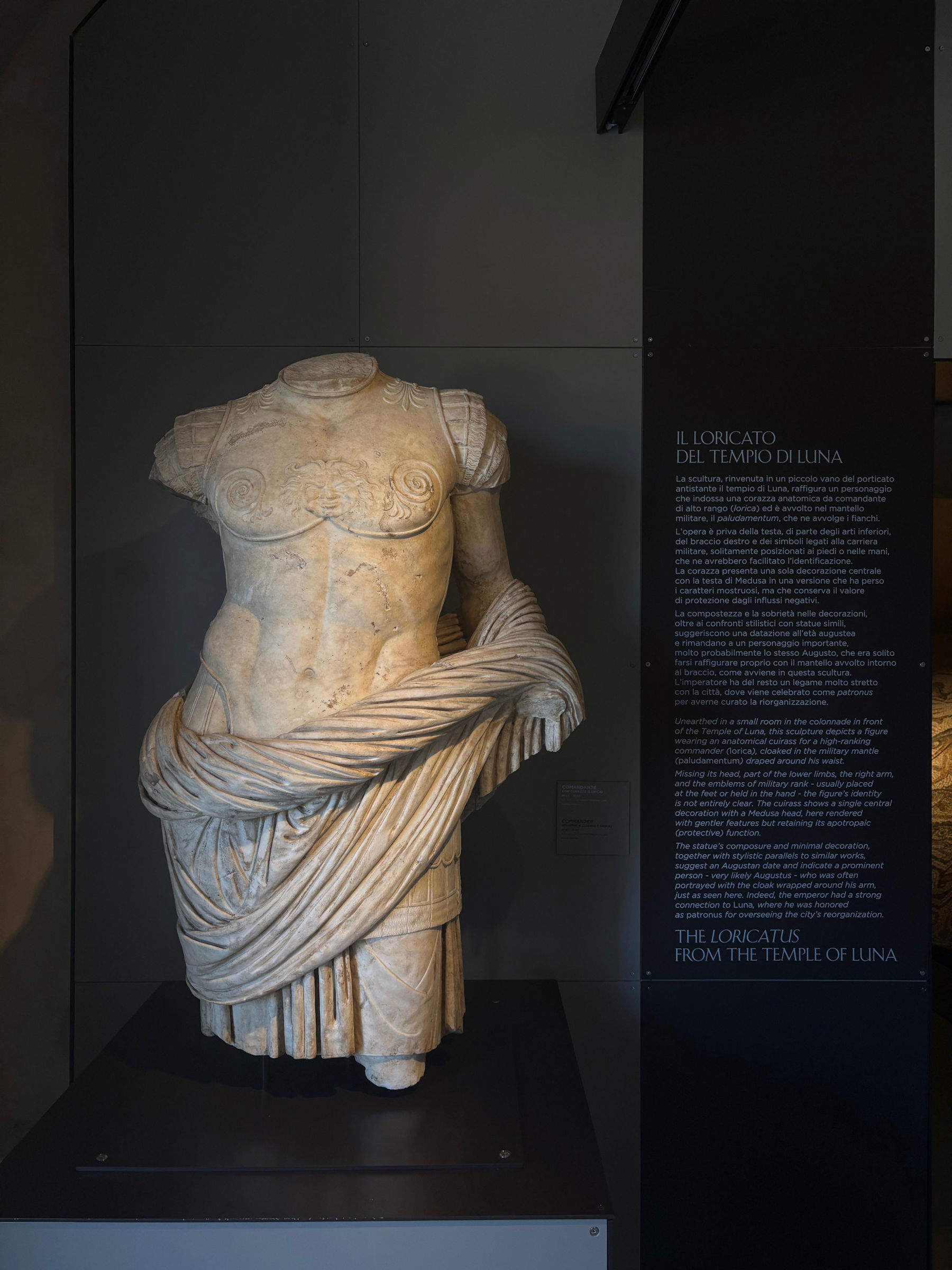

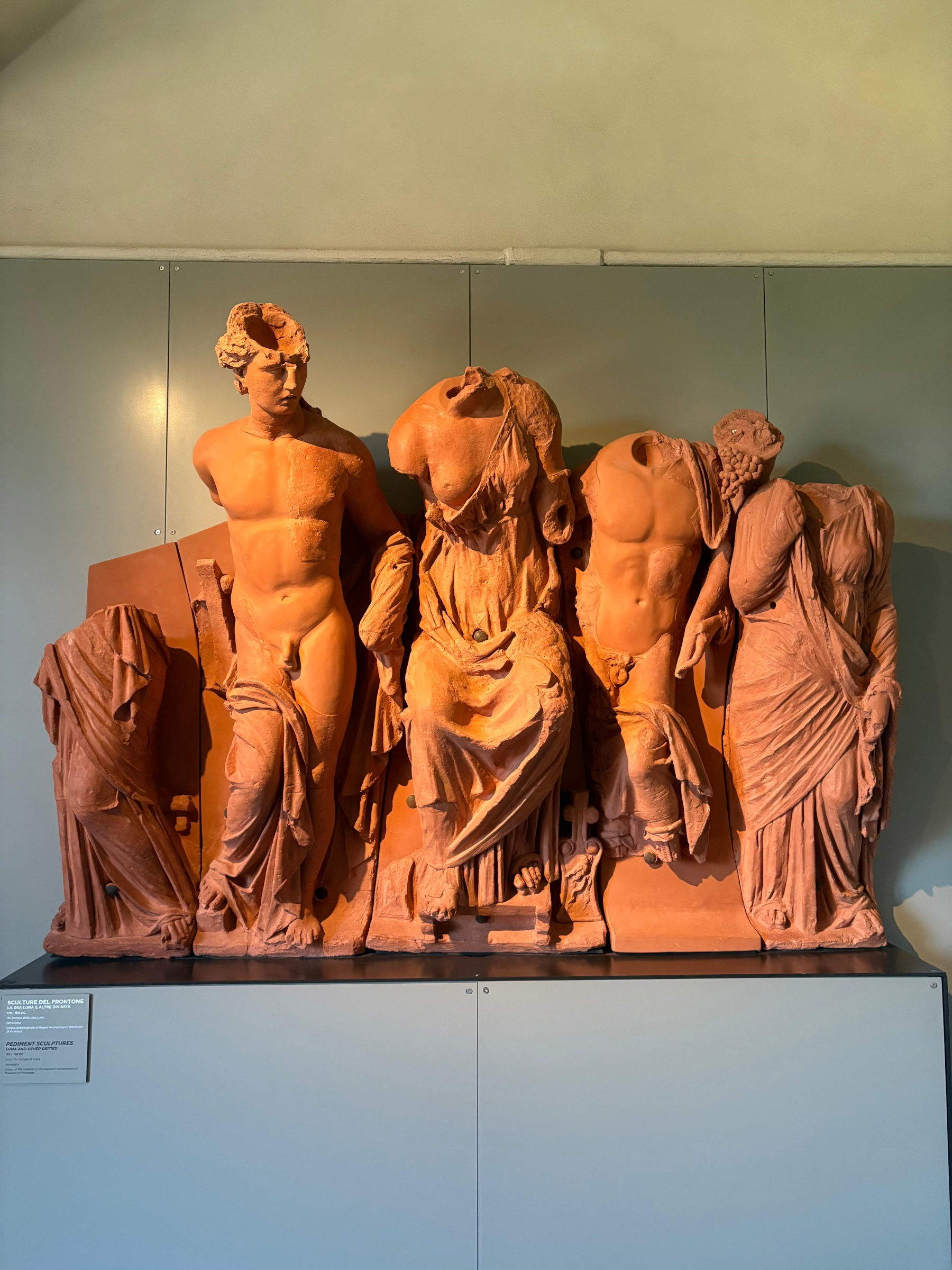

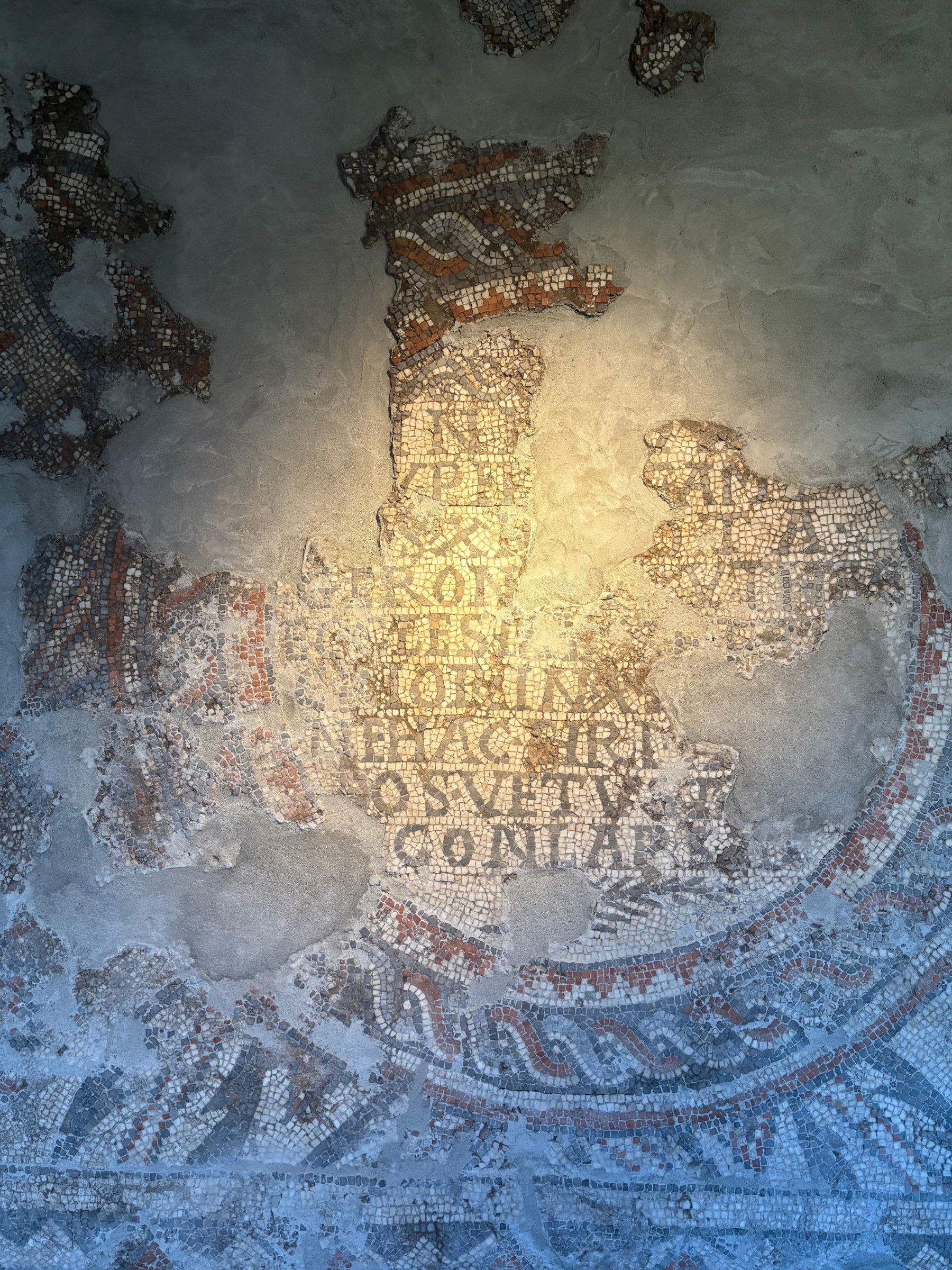

The new layout is spread over two floors. On the ground floor, the protagonist is Apuan marble, a founding element of Luni’s identity: used for statues, mosaics, and public and private architecture. Known finds, such as the votive base to the goddess Luna or the Ocean and Medusa mosaic, are on display alongside recent discoveries. A small room is dedicated to marble epigraphs, while a video room features documentaries from the Istituto Luce and original materials.

The upper floor follows a chronological narrative: from prehistoric tools found in the Luni area to Ligurian grave goods and Etruscan pottery, up to the founding of the Roman colony in 177 BC. Materials from the Capitoline temple and that of the goddess Luna are presented, along with evidence from the imperial phase: urban renovations, productive activities and objects of daily life. The narrative reaches into the Byzantine and Lombard periods, recounting the transformation into an episcopal seat and a place of pilgrimage on the Via Francigena. Luni’s history comes to a halt around 1200, when the port silted up and religious power moved elsewhere.

The idea of enhancing both the monumental and material aspects has thus become the guiding thread of the museum project, conceived as a grand opening to the Roman Luni, a refined and rich city. Some fragments of its architecture, were found in the northern porticos of the city, testifying to the very high artistic level achieved. Today, many of those works are preserved elsewhere, in La Spezia, Carrara, and Florence, but the city of Luna has been excavated for less than 10 percent of its extensive territory. For this reason, archaeologists confirm that much remains to be discovered, and that the area could become an active archaeological site for decades.

Currently, archaeological activity in Luni continues with new developments in several areas of the site. In some areas, the situation has been partially restored after the alteration due to the demolition of the museum and the beginning of the actual excavations. Interventions currently underway are not only concentrated in the central area, but also at strategic points such as the main southern roadway.

Every year, an excavation campaign lasting about a month and a half kicks off in the fall. In one of these campaigns, a new domus of great interest emerged, adorned with fine mosaics. Initially, the survey had been initiated with the aim of finding traces of port structures, given the proximity to the ancient port. Instead, what has come to light once again confirms the wealth of the local elites: this is a large, elegant and articulate private residence, a tangible sign of the affluence of its owners. However, what continues to be missing from the archaeological picture is the identification of the communal settlement, that is, the houses and structures that would have housed most of the population. This was also pointed out by a professor at the University of Pisa, reflecting on how the image returned by the excavations tells the story of luxury, yes, but still leaves unanswered the broader question: where did the thousands of inhabitants of Luni live? According to sources, the colony numbered about two thousand settlers, probably also distributed in the surrounding rural area, but material traces of habitation remain elusive.

Another excavation front is active in the cathedral area, where a study project on the evolution of the area in the early medieval period has been underway for several years. In fact, between the late 6th and early 7th centuries, at the height of the Byzantine era, the area was transformed into a fortified citadel around the cathedral, becoming one of the hubs of urban power. Two excavations are ongoing: one managed directly by the Superintendency, the other conducted by the University of Genoa with regular campaigns.

The excavations have yielded remains of wooden buildings, sheds and temporary structures, alternating with cemetery and landfill areas. A spotty urban pattern, now recognized in many Italian cities of the early Middle Ages, in which precarious dwellings, burials and productive spaces are linked.

Results such as today’s are the result of long and often silent processes. These are paths made up of research, study, restoration, complex and patient procedures, faced through major obstacles. The achievement of a project of this magnitude is therefore a concrete satisfaction. Preserving and passing on cultural heritage to future generations is one of the fundamental goals of institutions, but it does not end with the task of conservation alone. Places like the ancient Moon, returned today to the community, have the potential to become vital centers for the communities that inhabit them. For this to happen, it is therefore necessary to adopt new languages capable of engaging diverse and increasingly heterogeneous audiences.

|

| Luni opens new national archaeological museum |

The author of this article: Noemi Capoccia

Originaria di Lecce, classe 1995, ha conseguito la laurea presso l'Accademia di Belle Arti di Carrara nel 2021. Le sue passioni sono l'arte antica e l'archeologia. Dal 2024 lavora in Finestre sull'Arte.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.