From the Latin primitivus, “first in order of time,” the term “primitive” is used to describe a period before the present. When early humans began to explore the land, seas, rivers and discover fire, their dawning was marked by a profound moment of darkness. The crisis that plagued primordial man manifested itself as the first questions arose, which he could not answer. His quest became an agitated one, both to find answers to the daily mysteries that surrounded him and to understand the natural phenomena he observed with awe: the rising of the sun in the morning, the appearance of the first stars in the evening, the rain. In primitive man’s thoughts there was an invisible connection between what was part of the surrounding nature and what he considered supernatural, such as thunder and wind. The thought of supernatural benevolence toward humans would thus have been the fundamental theme of all artistic practice that developed during Prehistory.

Through the thought of divine power and to an early approach to a religion with rudimentary traits and an unrelenting thirst for curiosity, primitive man was able to give birth to myth: the only explanation, non-rational and devoid of philosophical and scientific thought, capable of explaining the mysteries of existence. Only with the advent of writing and the beginning of classical history and civilizations did the term “myth” take on a well-defined meaning. Its function was to explain, pass on and offer a comprehensive view of the ancient world and its historical, religious and natural beliefs. Among the Creation myths, the Cosmogonic Myths occupy a significant role. In an ancient landscape of cosmogonic mythologies, among all, Egyptian thought attempted to explain the origin of the universe through a more familiar and accessible concept, using biological phenomena rather than the principles of Greek philosophy, which was more abstract and conceptual. Of all the symbols related to creation, the egg is found in various cultures and cosmogonies around the world. Currently, astronomical cosmology holds that about 13.7 billion years ago, the entire mass of the universe was compressed into an extremely small volume, approximately thirty times the size of our Sun. From this point of extreme density, known as the Big Bang, the universe expanded over time to its present state, following a process similar to the hatching of an egg. InHinduism, the image of the cosmic egg bears remarkable similarities to the concept of the primordial core of the Big Bang theory. It speaks of the golden womb (Hiranyagarbha), a universal core that floated in the primordial ocean immersed in the darkness of nonexistence. When this womb hatched, Brahmā, the creator of the universe, is said to have infused the breath of life through the sacred syllable Aum, considered the primordial sound. From the golden top of the egg thus emerged the sky, while from the silver bottom the earth was born. Always therefore associated with the creation and origin of the universe, the egg contains the embryo of life evoking the bliss of a primordial stage of peace. The same bliss is sought by various characters portrayed by Hieronymus Bosch (’s-Hertogenbosch, 1453 - 1516) in his famous painting The Garden of Delights, made about 1480 - 1490. However, in Bosch’s painting, the egg depicted is shattered and individuals plunge directly into it, yearning for a return to a state of peace.

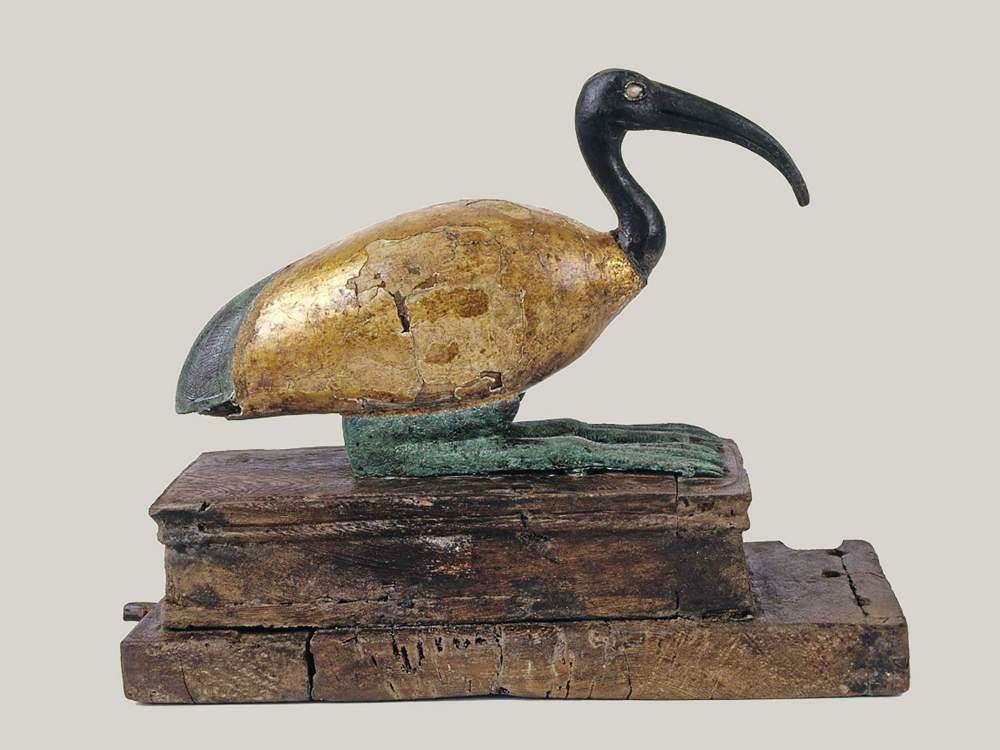

The perceivable characteristic of the egg is that it is the receptacle of something germinal destined to evolve into a molded reality. It lends itself to mythological thought, taking on an important symbolic value indicating origin, similar, for example, to the concept in Egyptian cosmogony and theogony, in which the figure of Amun, the Egyptian deity at the head of the entire Pantheon is, among its various depictions, represented by a goose that, according to myth, would lay the primordial cosmic egg from which life would be generated. A similar concept is found in the divine figure of Thot, god of knowledge and writing among the main deities of the Egyptian Pantheon. Thot could manifest himself in two distinct zoomorphic forms: that of an ibis and that of a baboon. According to mythology, Thot was considered the son of the sun god Ra, born directly from his lips at the beginning of creation. Other versions of the mythologies point to him as the son of Horo, while still others narrated that Thot generated himself at the beginning of time and that in the form of an ibis he laid and hatched the cosmic egg that contained the entire creation. In Greek Orphic cosmogony, on the other hand, the figure of Phanes, also called Erikepaios (giver of life), is a primal figure of the origin of life. Unlike Amun, who generated the egg of life, Phanes himself is the god born from the cosmic egg laid by Chronos (Time) and Ananke (Destiny, Necessity). In this common Greco-Eastern context, the link between the breaking of the egg and the simultaneous creation of heaven and earth occasionally emerges, representing the fundamental and earliest cosmogonic moment.

The symbolism of the egg is also taken up in other Greek myths. In the tale of Leda and the Swan, the young woman is said to have hatched an egg that was later brought forth by Nemesis, beloved of Zeus. From the egg Helen of Sparta would be born, as reported by the Greek poet Stasinus in his Ciprie. In a second version, which already appears in Homer’s work, it is told that Leda united with Zeus, who had turned into a swan, and together they laid one or more eggs, from which Pollux and Helen were born. Following her marriage to Tindarus, Leda would instead have Timandra, Clytemnestra, Philonoe and Castor. In Orphic mythology, which is characterized by the conception of reincarnation and the cyclical nature of the Universe, the cosmic egg takes on further significance, representing the repetition of the birth of the Cosmos.

Through the concept of reincarnation, in later centuries the symbolism of the egg became the symbol of Christ’s resurrection, as depicted in the Brera Altarpiece. Created in about 1472 by Piero della Francesca and currently housed at the Pinacoteca di Brera in Milan, this work represents the pinnacle of the master’s artistic thought. In addition to Duke Federico di Montefeltro, depicted as a knight, it features his wife Battista Sforza, depicted with the features of the Madonna, and his son Guidobaldo. The depiction is built on a central perspective, the centerpiece of which is an ostrich egg that descends from the ceiling in the shape of a shell and, like a pearl, remains suspended just above the face of the Madonna. The egg becomes at the same time a symbol of the purity and perfection of the Holy Child’s conception and her future Resurrection. In traditional iconography, Mary Magdalene, a follower and disciple of Christ, is often depicted holding a red-shelled egg, a symbol of her ardent desire to witness Christ’s Resurrection with strength and courage. This particular iconographic element can be seen in the work St. Mary Magdalene painted by the Italian painter Segna di Bonaventura around 1320 and currently housed in theAlte Pinakothek in Munich.

Later, in the Pre-Raphaelite period the figure of Magdalene holding an egg (or sometimes a vase) was taken up by Dante Gabriele Rossetti (London, 1828 - Birchington-on-Sea, 1882) in his Mary Magdalene . The first is an 1867 draft; in the second version, in an 1877 oil painting preserved in the Delaware Art Museum in Wilmington, she appears framed by a wreath of flowers and leaves. The piercing gaze and colors on the green tones of her surroundings and dress contrasted with the reds of her plump lips and flowing hair give Rossetti’s Magdalene an ethereal and divine aura to her appearance, accentuated by the golden lighting that grazes her skin. In modern times, however, Surrealist artist Salvador Dalí (Figueres, 1904 - Figueres 1989) reinterpreted the egg as a universal symbol of creation and birth. In his 1948 work The Dawn, the embryological egg generates a bright sun, whose rays of light brighten the clouds and surroundings, giving birth to the new day. Later, in the 1950 Madonna of Port Lligat, a year after the first version, Dalí offers a different surrealist vision of the symbolism of the element, recalling the arrangement of the egg in Piero della Francesca’s painting, which descends from the ceiling in the shape of a shell. In the work, we see the figure of the seated Madonna, impersonated by Gala, Dalí’s wife and muse in real life, with the Christ child on her lap, a symbol of divine and human love. The work is currently on display at the Art Gallery in the city of Fukuoka, Japan.

Just in Japan, the iconography of the egg of life emerges in the cosmogony of the Nihongi, also known as the Chronicles of Japan, a literary corpus that collects the earliest written accounts of the country’s history. This work dates from the period between the 7th and 8th centuries CE. Among the various themes covered in this text, the image of the egg is mainly interpreted as a symbol of the primordial state in which the two fundamental principles, the feminine(yin) and the masculine(yang), live in harmony. When these principles separate, heaven and earth are created, thus giving rise to the world according to this cosmogonic perspective. In Zoroastrian cosmological traditions, however, the egg takes on a radically different meaning. It is consistently represented as the form of the already configured world, often emphasizing its sphericity, as in the symbolism of the shell entirely enveloping the earth. In these conceptions, it represents the world as a complete and self-sufficient entity, enclosed and protected within its shell.

Therefore, while today the gesture of giving Easter eggs may seem related primarily to the Christian holiday, it is important to recognize its more ancient and universal roots that reflect new beginnings, the cyclical nature of life and its renewal.

The author of this article: Noemi Capoccia

Originaria di Lecce, classe 1995, ha conseguito la laurea presso l'Accademia di Belle Arti di Carrara nel 2021. Le sue passioni sono l'arte antica e l'archeologia. Dal 2024 lavora in Finestre sull'Arte.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.