by Redazione , published on 29/10/2018

Categories: News Focus

/ Disclaimer

Leonardo da Vinci's Codex Leicester arrives in Italy for the first time since 1986. It is featured in the exhibition "Nature's Microscope Water. Leonardo da Vinci's Leicester Codex."

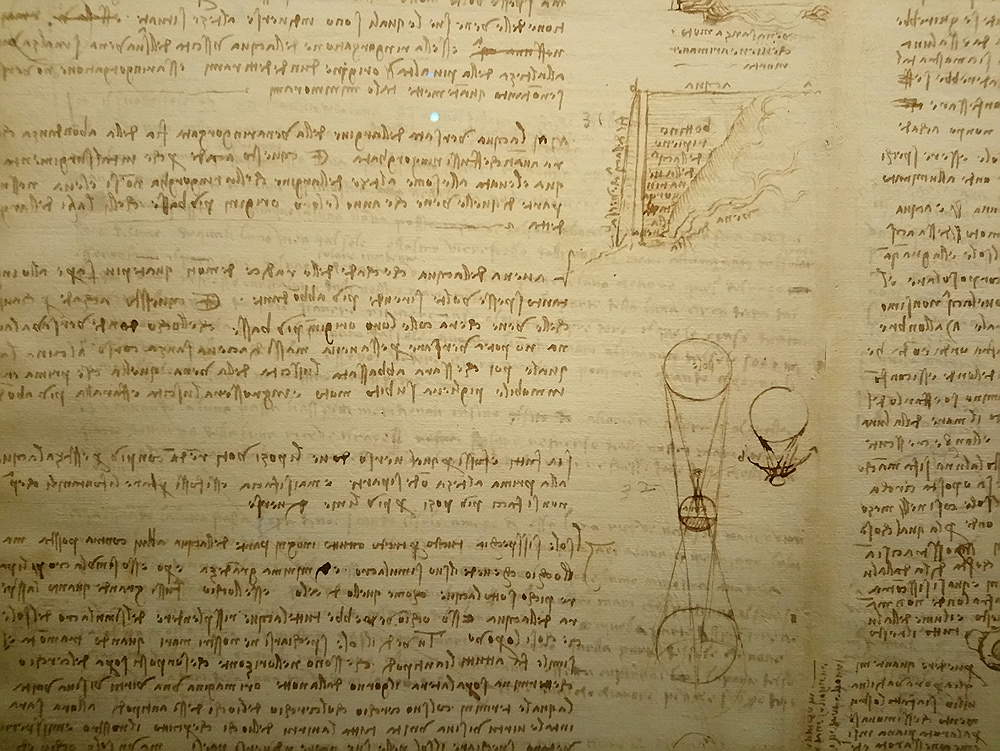

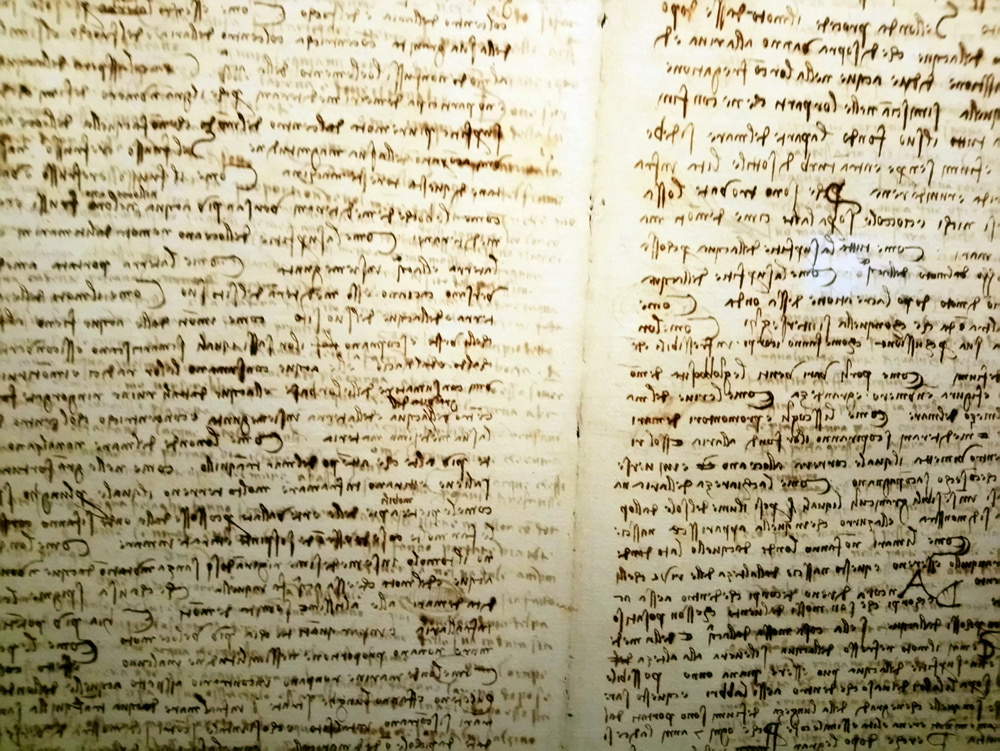

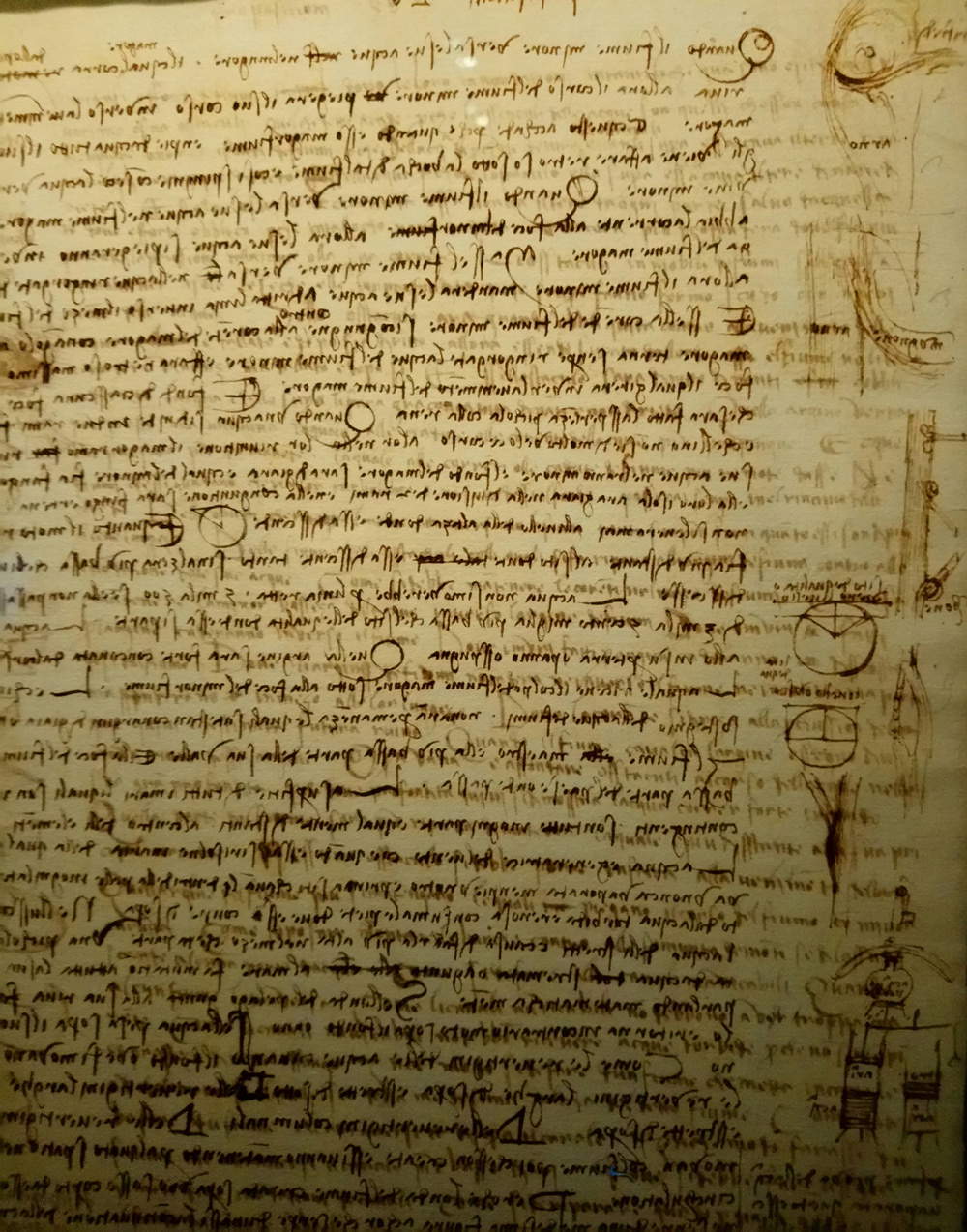

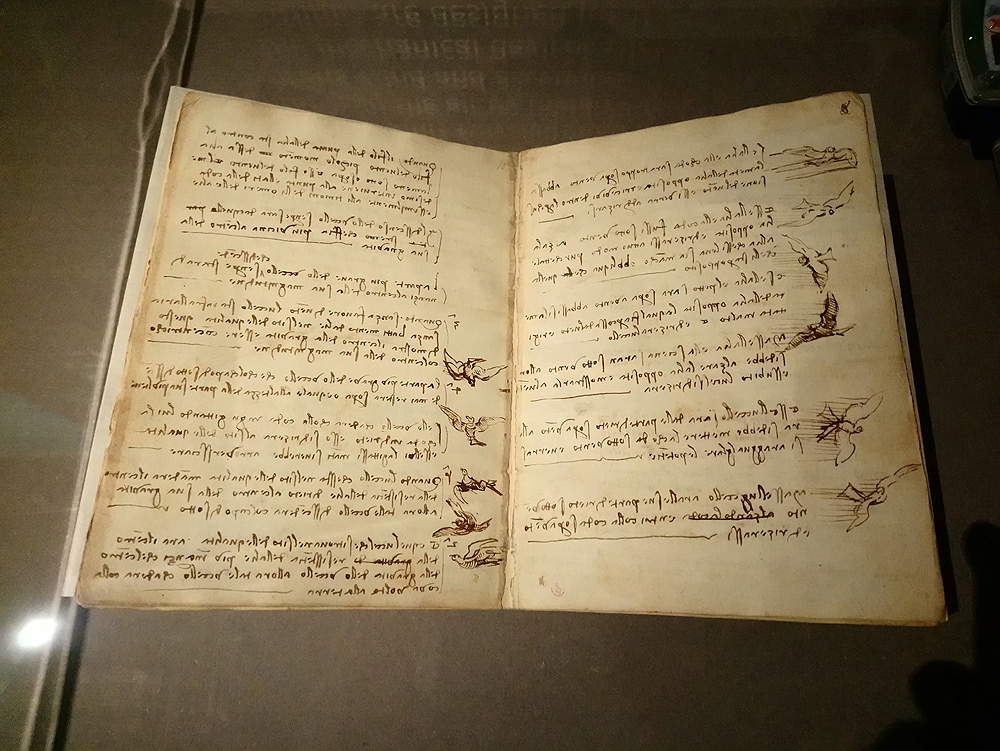

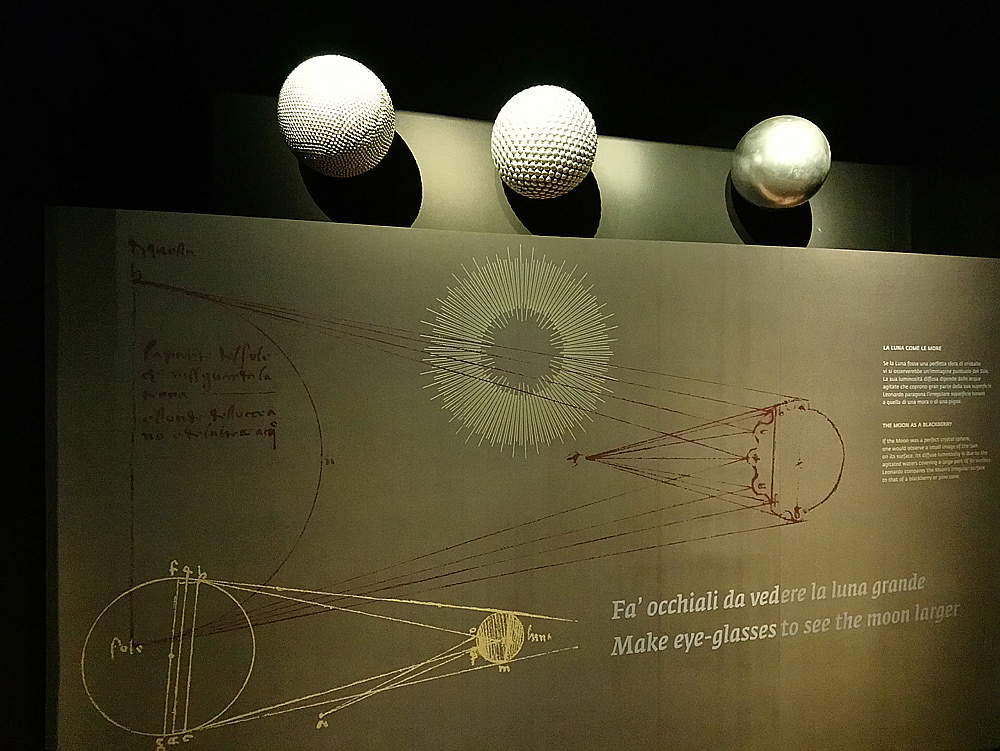

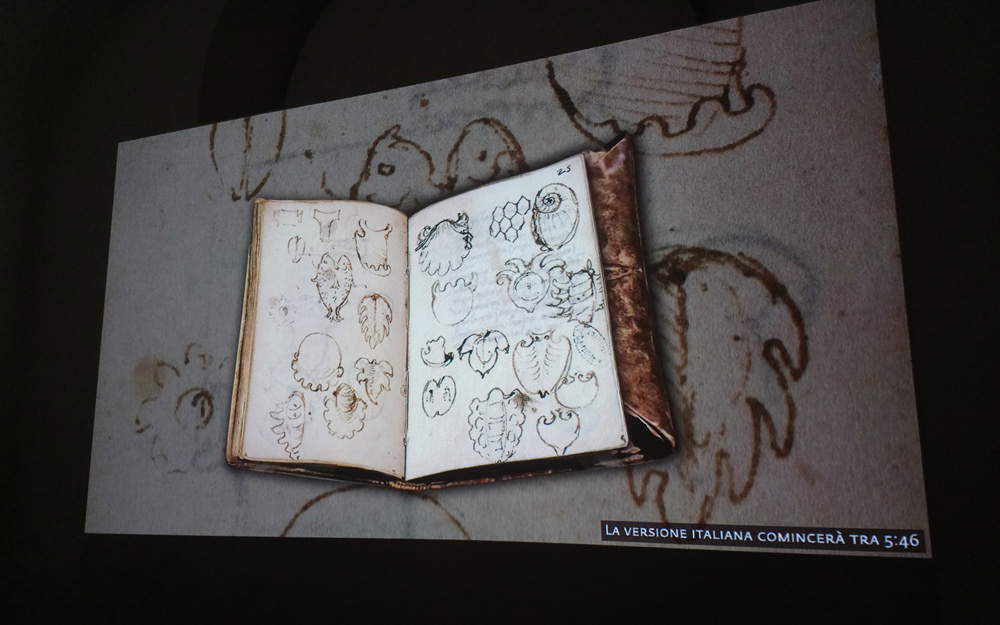

It opens on October 30, 2018, and ends on January 20, 2019, the exhibition The Water Microscope of Nature. Leonardo da Vinci’s Codex Leicester, which brings back to Italy, and to theMagliabechiana Hall of the Uffizi in Florence to be precise, Leonardo’s precious manuscript, composed of 36 sheets totaling 72 pages of notes, theories, and drawings. The arrival of the Leicester Codex represents a preview of the celebrations for the 500th anniversary of the death of Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci, 1452 - Amboise, 1519), which will animate all of 2019. The exhibition, curated by Paolo Galluzzi, has been organized by the Uffizi in collaboration with the Museo Galileo in Florence and with the contribution of the Fondazione CR Firenze: the public will have the opportunity to see the Codex, written largely between 1504 and 1508, years of Leonardo’s great and intense artistic and scientific activity, up close. In the Codex, in fact, many of his theories on the moon, water and waterways, fluids and much more can be found: to help the visitor in reading the Codex will also intervene the Codescope, a digital tool thanks to which it is possible to browse, in very high resolution digital representation, all the pages of the manuscript (with magnification functions, transcription/translation in English of the texts, mirror reversal of Leonardo’s left-handed writing, etc.). The Codescope provides visitors with a tutor who illustrates in a concise but rigorous manner the most significant themes that are analyzed there. The exhibition also features some very valuable original and autograph folios from the Codex Atlanticus, the Codex Arundel and the Codex on the Flight of Birds, respectively owned by the Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milan, the National Library in London and the Biblioteca Reale in Turin: these are all folios compiled by Leonardo at the same time as the Codex Leicester.

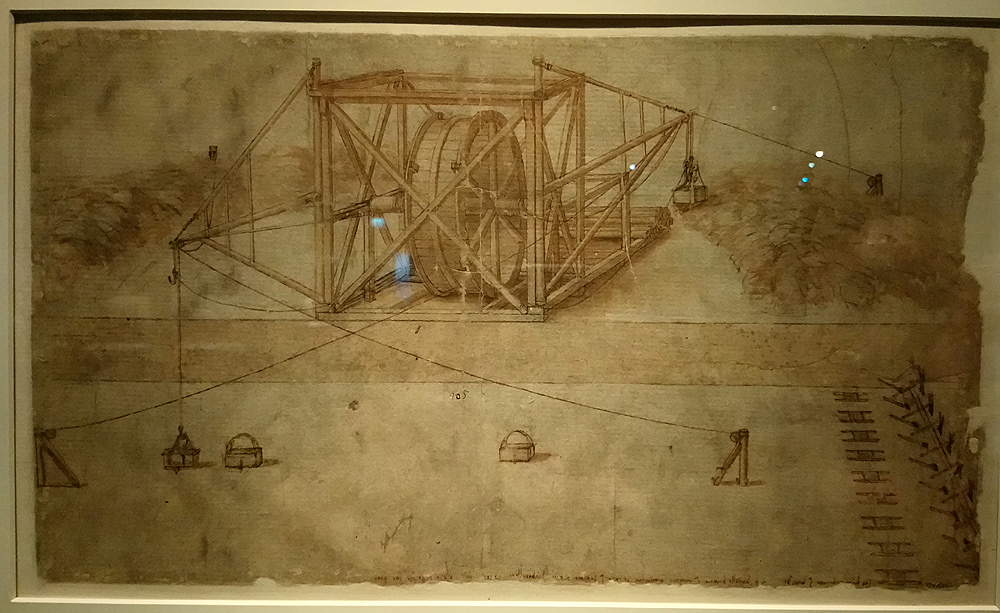

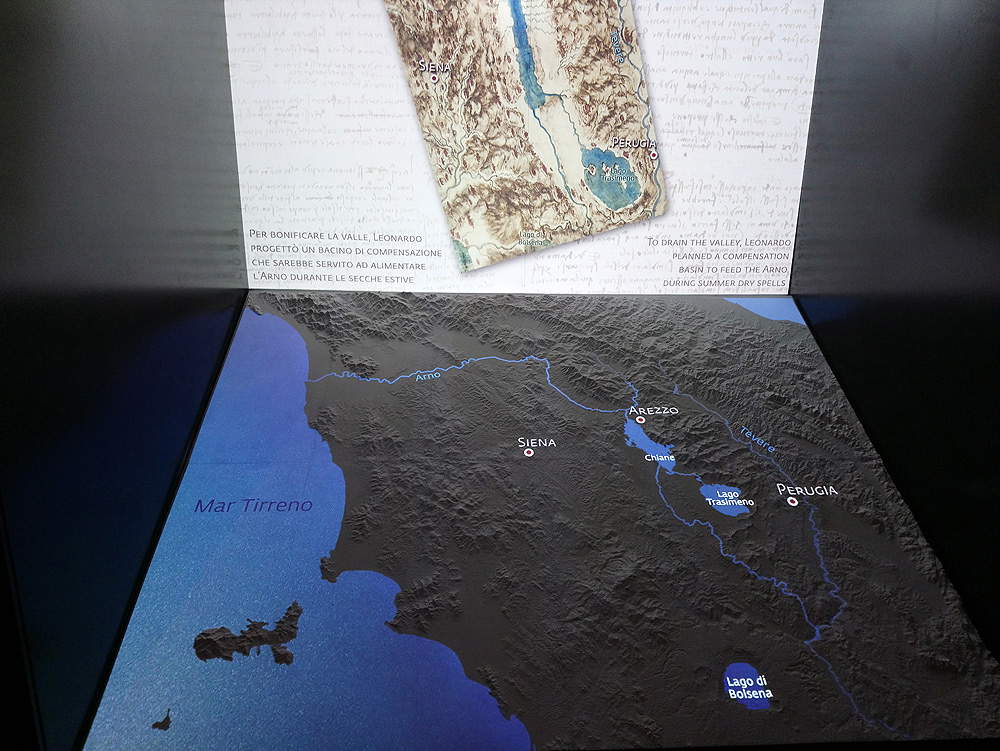

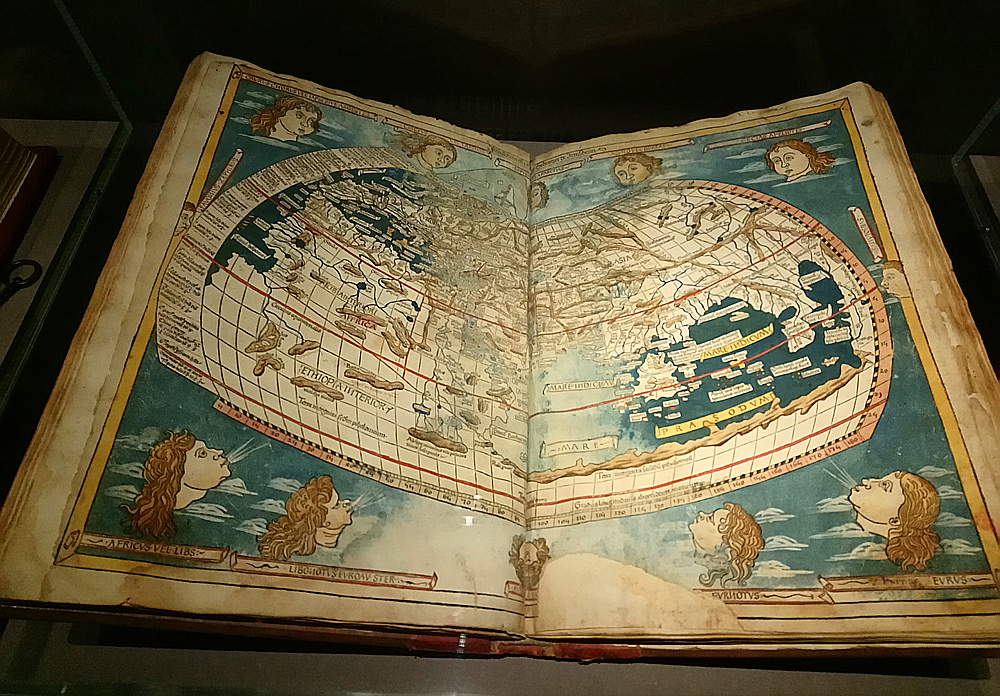

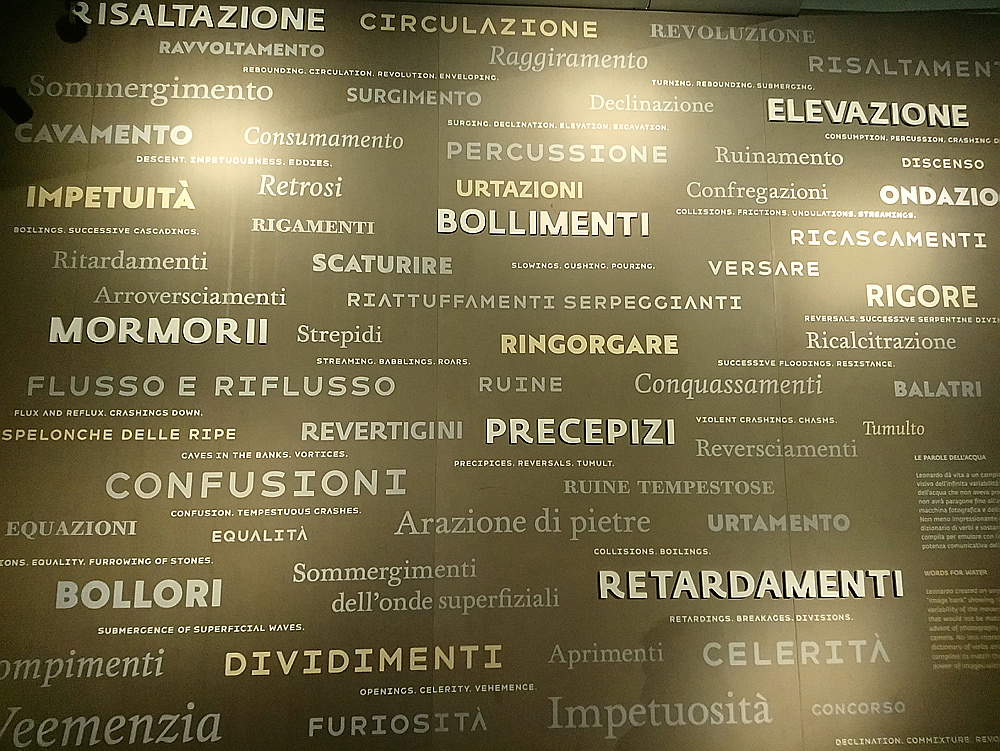

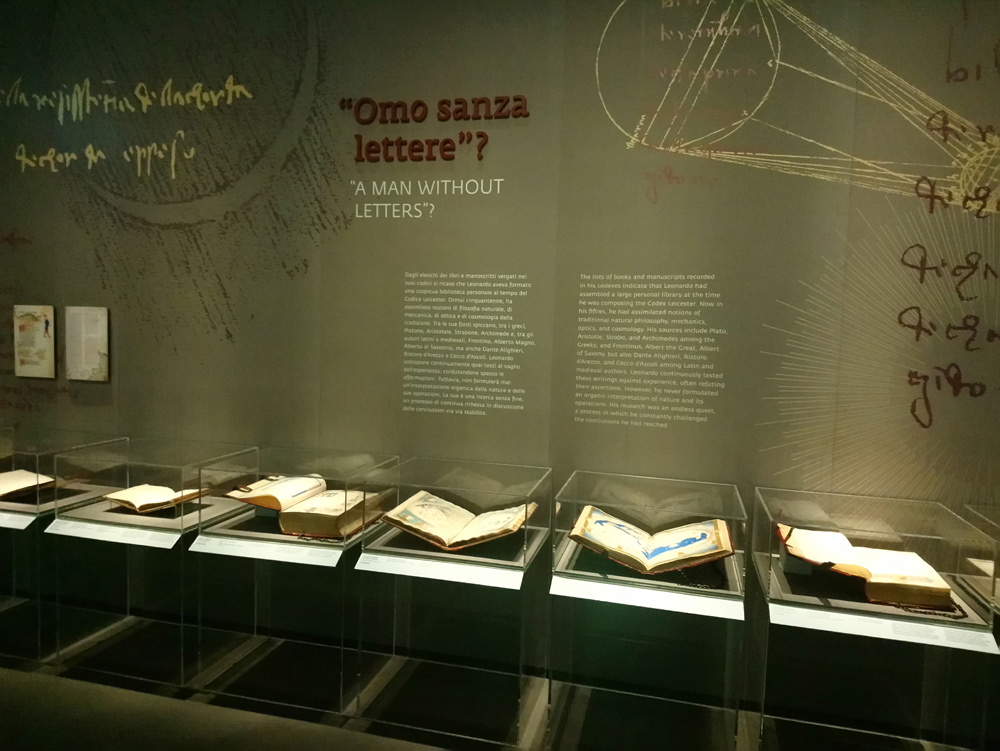

The exhibition route begins with a series of display cases that are intended in a way to dispel the myth of Leonardo da Vinci as a man without letters: in fact, volumes that Leonardo knew very well are displayed (the artist, now in his 50s, knew among the Greeks Plato, Aristotle, Strabo, Archimedes, among Latin and medieval authors Frontinus, Albertus Magnus, Albert of Saxony, as well as Dante Alighieri, Ristoro dArezzo and Cecco dAscoli). At the end of the tour, a video of about 8 minutes is shown, in Italian and English, in which his theories on the role of water in the evolution of the planet from prehistory to his own time are collected. In addition to vitrines displaying the original pages of the Codices and other manuscripts, lent for the occasion by other prestigious institutions, the public will find large panels and digital screens that narrate, also with animations, the flight of birds, the flow of water from rivers and wave motion from the seas, the effects of tides, the moon of water drops and soap bubbles, of the principle of the constancy of equal flow both in the confluence of two rivers and in the organization and functioning of blood circulation in humans, of the futuristic project of the navigable canal on the Arno from Florence to the sea, of the machines to make it, to operate a large crane, and to measure great distances on the ground. The exhibition is also “animated” by the projection on the floor of the falling of water drops and the flowing of streams: the visitor almost feels the effect of dipping his feet into them, like Christ and the Baptist sinking ankle-deep into the Jordan River in the Baptism of Christ painted by Leonardo together with his master Verrocchio and exhibited, in the new room dedicated to da Vinci, only two floors above, at the Uffizi.

The exhibition, as curator Galluzzi recalls, is a sort of remake of the 1982 one, during which the Leicester Codex was seen by some 400,000 visitors: “In 1982,” the curator recounts, “I had the privilege of collaborating with Carlo Pedretti on the creation of the third (after those in Washington and London) in the series of international exhibitions that featured the Leicester Codex (then called Hammer after the California tycoon who had bought it from its ancient owner at the Christies auction in December 1980). Curated by Pedretti himself, who was Hammer’s listening adviser, the Florentine presentation was staged in the splendid setting of the Quartieri Monumentali in Palazzo Vecchio. The season of major exhibition events capable of attracting the interest of the wider public had just begun. In fact, the great kermesse of the Medici Exhibitions set up in the most prestigious containers of the City of the Lily, which recorded almost two million visitors, had closed its doors a few months ago. Nor was the reception reserved for the Hammer Codex any less warm: in little more than three months there were more than 400,000 Italian and foreign citizens and tourists who paraded admiringly in front of the showcases that contained the eighteen bifolios of the manuscript resulting from their removal from the binding in which they were previously enclosed. An operation suggested by Carlo Pedretti, on the basis of solid scientific reasons, to restore to that precious manuscript the appearance it had when it was in Leonardo’s hands.” Moreover, the exhibition catalog is dedicated to the memory of Carlo Pedretti.

There are three objectives of the exhibition for Paolo Galluzzi: to draw attention to the context within which Leonardo wrote the pages of the Codex, to foster understanding of the contents of the Leicester Codex through a very thorough didactic apparatus, and finally to emphasize how, in several pages of the Codex, Leonardo anticipates many modern scientific theories. “The opportunity to admire up close the seventy-two pages, filled with texts, sketches and drawings, of the Leicester Codex,” Galluzzi concludes, “is not the only privilege offered to visitors to the exhibition set up in the spaces of the Uffizi Galleries. Indeed, they make a worthy crown to that witness of Leonardo’s ingenuity other documents of exceptional value. It will be worth mentioning, first and foremost, the presence of the Codex on the Flight of Birds, compiled in Florence in the same months and years in which Leonardo was working on the drafting of the Leicester Codex. Other masterful drawings of his also embellish the exhibition itinerary: those depicting the face of a Moon with its surface covered by oceans in perpetual agitation that he considered the Earth’s perfect twin; the beautiful portraits he produced of machines to make the removal of excavated materials in canal works more expeditious; and the evocative depictions of the course of the Arno as it passes through Florence, with precise indications of the bridges that connected the two banks. Not to mention the manuscripts and printed publications of ancient and medieval authors with whom he maintained a dense dialogue always characterized by strong critical autonomy.”

“The Leicester Codex,” declares instead the director of the Uffizi, Eike D. Schmidt, “returns to Florence after thirty-six years, having recovered the name of its first English owners, the Earls of Leicester by whom it was known until 1980, before being purchased by Armand Hammer; and with a brand new critical apparatus. The Uffizi Galleries have now decided to offer this opportunity also to the new generations, who had not been able to see the sheets of Leonardo’s precious manuscript in the Florentine exhibition of 1982 beautiful but more reduced nor in the Bologna exhibition of 1986 focused mainly on the Emilian outcomes and on the famous Map of Imola, preserved among the English crown’s properties, at Windsor. This is not because they wanted to create an ad hoc occasion to celebrate the 500th anniversary of the artist’s death, which the whole world is preparing for with various initiatives. But because Leonardo, his art, and his writings, are constantly evolving subjects, and not a year, or month, goes by in which no new information about his work, the result of studies or discoveries, does not emerge; and so it was time to share with the public the results of these last three decades. The return to the Uffizi, after five years of investigation and restoration by the Pietre Dure factory, of the great panel depicting the Adoration of the Magi is very recent: the subject of hundreds of publications, even appearing in famous films, on this occasion it nevertheless showed, to experts in the field (and now to visitors), novelties that until recently were not appreciable and allowed advances in the studies of the art of the genius of Vinci. The same is now happening with the Leicester Codex, which moreover in the exhibition benefits from the great advantage of a highly advanced technology the Codescope to obviate the difficulties of displaying and making use of all the individual sheets; and to guide the observer through the deciphering of its contents. The exhibition set design benefits from these innovations, which certainly help to bring Leonardo’s complex texts closer and explain them to the visitor.”

Below, we offer a selection of images from the exhibition.

|

| Images from the exhibition The Water Microscope of Nature. Leonardo da Vinci’s Codex Leicester. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Images from the exhibition The Water Microscope of Nature. Leonardo da Vinci’s Leicester Codex. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Images from the exhibition The Water Microscope of Nature. Leonardo da Vinci’s Leicester Codex. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Images from the exhibition The Water Microscope of Nature. Leonardo da Vinci’s Leicester Codex. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Images from the exhibition The Water Microscope of Nature. Leonardo da Vinci’s Leicester Codex. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Images from the exhibition The Water Microscope of Nature. Leonardo da Vinci’s Leicester Codex. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Images from the exhibition The Water Microscope of Nature. Leonardo da Vinci’s Leicester Codex. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Images from the exhibition The Water Microscope of Nature. Leonardo da Vinci’s Leicester Codex. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Images from the exhibition The Water Microscope of Nature. Leonardo da Vinci’s Leicester Codex. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Images from the exhibition The Water Microscope of Nature. Leonardo da Vinci’s Leicester Codex. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Images from the exhibition The Water Microscope of Nature. Leonardo da Vinci’s Leicester Codex. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Images from the exhibition The Water Microscope of Nature. Leonardo da Vinci’s Leicester Codex. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Images from the exhibition The Water Microscope of Nature. Leonardo da Vinci’s Leicester Codex. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Images from the exhibition The Water Microscope of Nature. Leonardo da Vinci’s Leicester Codex. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Images from the exhibition The Water Microscope of Nature. Leonardo da Vinci’s Leicester Codex. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Images from the exhibition The Water Microscope of Nature. Leonardo da Vinci’s Leicester Codex. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.