The XXXI edition of the Florence Biennale Internazionale dell’Antiquariato, one of the world’s most important antique art exhibition-markets, is scheduled for Sept. 21-29. 77 participating galleries, many fine works (several would fit well in our museums), very high quality. We were at the preview and offer what we think are the ten most interesting works at BIAF.

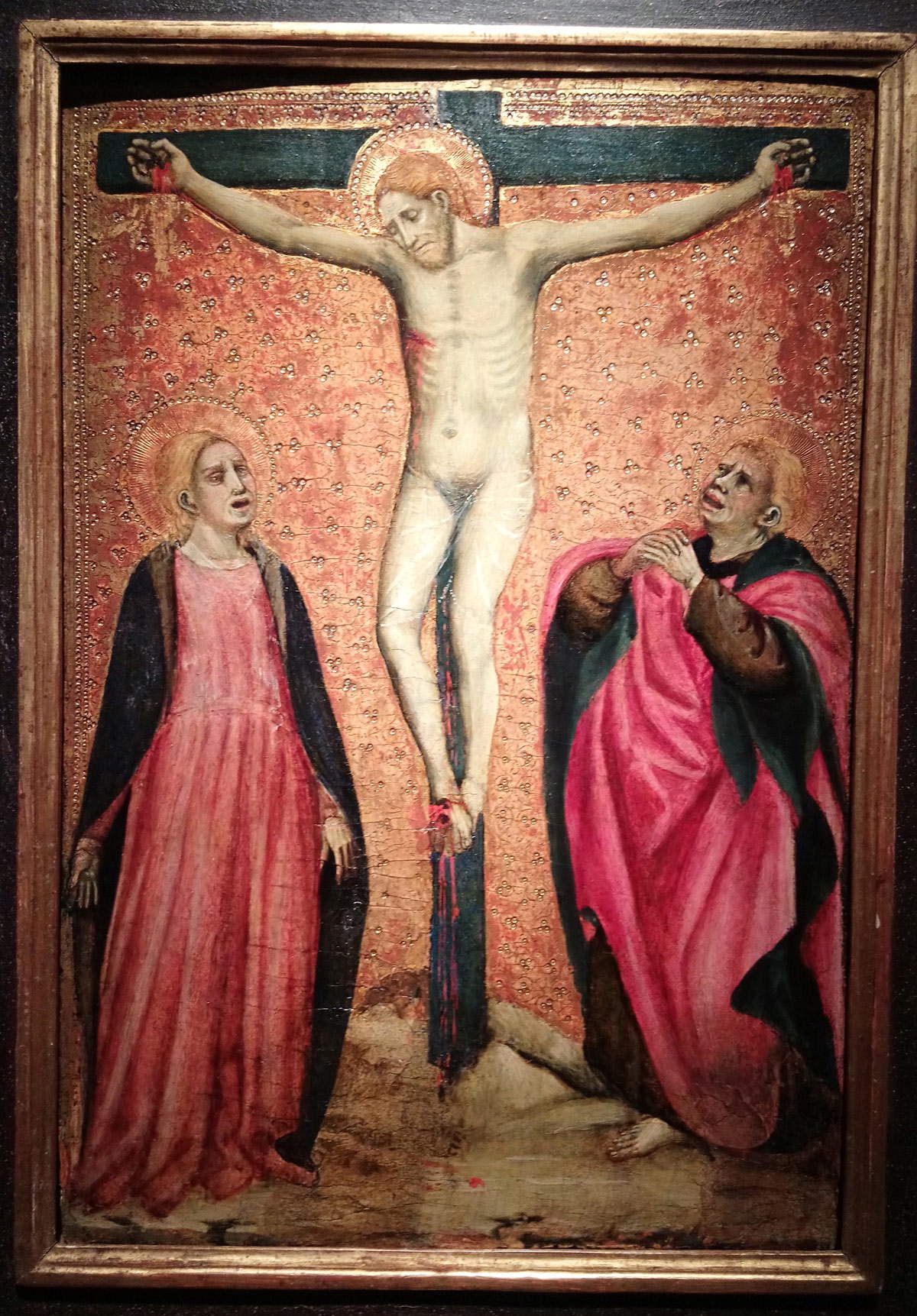

1. Giovanni Antonio da Pesaro, Crucifixion (circa 1430), presented by Salamon Gallery.

Prominent among the gold backgrounds presented at this edition of BIAF are those from the Salamon Gallery, including a Madonna and Child with Saints given by Angelo Tartuferi to the 15th-century Florentine painter Ventura di Moro, a work from around 1430, and a coeval crucifixion by Giovanni Antonio da Pesaro (Pesaro, c. 1415-before 1478), a work with a long critical history (it is cited in Longhi, Volpe and others). The angular faces with strongly accentuated wrinkles and expressions, the late Gothic tortuosities and elongations, and the highly expressive gazes (note the grimaces of pain), are typical of the stylistic signature of this artist active in the Adriatic area. In addition, Salamon presents other important works at BIAF, and there is also room to take a look at the Ringli Triptych attributed to the Master of St. Ivo, recently acquired by the church of San Pietro di Avenza (Carrara).

|

| Giovanni Antonio da Pesaro, Crucifixion (c. 1430; tempera on panel with gold ground, 42 x 28.5 cm) |

2. Attributed to Verrocchio, Carthaginian Hannibal (ca. 1500), presented by Frascione Arte

The public will remember seeing this Carthaginian Hannibal at the recent Verrocchio exhibition held at Palazzo Strozzi earlier this year: on that occasion, the sculpture presented at BIAF by Frascione figured as a new attribution to Verrocchio. Attribution, at any rate, far from certain: it could be a relief that in ancient times was displayed facing a relief depicting General Scipio, who defeated Hannibal (and indeed at the Palazzo Strozzi exhibition it had been presented together with the Louvre’s Scipio). Frascione’s relief was modified between the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, when, to better meet the taste of the time, it was given its present oval shape. In the catalog entry for the Palazzo Strozzi exhibition, Paolo Parmiggiani noted the iconographic affinities with the Louvre’s Scipio: “the shell-like structure of the helmet, the shape of the dragon, the pair of ribbons falling on the back, the scaled larmature, the Screaming Fury, the phytomorphic decoration parading over the shoulders.” The debate around this work is as open as ever: a work perhaps not among the most beautiful, but certainly among the most interesting to discuss.

|

| Attributed to Verrocchio, Carthaginian Hannibal (ca. 1500; marble, 42.9 x 32.6 x 11 cm) |

3. Domenico Beccafumi, Holy Family with St. Giovannino (ca. 1515), presented by Carlo Orsi Gallery

This Holy Family with St. John by Domenico Beccafumi of Siena (Montaperti, 1486 - Siena, 1551) is one of the stars of this XXXI edition of BIAF. The work has a long exhibition history and is attested in ancient times to have been in the collection of the Sienese writer Girolamo Bargagli, who lived between the first and second halves of the 16th century. The elongated proportions, the fixed gazes, the somber tones, and some debt to the art of Fra Bartolomeo place this Holy Family in relation to other similar works Beccafumi produced in the mid-1610s. Also of note at Orsi’s is a bronze bust of Urban VIII by Gian Lorenzo Bernini.

|

| Domenico Beccafumi, Holy Family with St. John the Baptist (c. 1515; oil on panel, 86.2 x 75 cm) |

4. Ludovico Brea, Madonna and Child with Announcing Angels (c. 1520), presented by Altomani & Sons

The general public got to see this work recently at the Secret Renaissance exhibition curated by Vittorio Sgarbi in Pesaro in 2017, but the Madonna and Child with Announcing Angels by Ludovico Brea (Nice, c. 1450 - c. 1522/1525), the greatest exponent of the Ligurian Renaissance, has quite a long critical history (in the 1930s Berenson also mentioned it in his book Italian Pictures of the Renaissance). The work is an example of the great elegance of this artist who interpreted Renaissance novelties by looking at coeval Provençal painting (for example, at Enguerrand Quarton) but also at the Flemish masterpieces of Jan van Eyck and Rogier van der Weyden, without of course neglecting the contacts between Liguria and Lombardy that we know were frequent at the time.

|

| Ludovico Brea, Madonna and Child with Announcing Angels (c. 1520; oil on panel, 88 x 62 cm) |

5. Roelant Savery and Hans Savery II, Coastal Landscape with Fishermen in Front of a Saracen Tower (ca. 1613-1614), presented by Caretto & Occhinegro

Those who frequent antique art fairs know that the Caretto & Occhinegro gallery (which, moreover, is a newcomer to BIAF) always presents high quality Flemish works, and for the XXXI edition of BIAF, too, they do not disappoint. By the gallery owners’ own admission, their most important work, partly because of its connection to Italy, is this landscape by Roelant Savery (Kortrijk, 1576 1639) and his nephew Hans Savery II, also known as Jan Savery or Hans Savery the Younger (Haarlem, 1589 - Utrecht, 1654). Dutch painters working in the early seventeenth century, the Saverys were probably also in Italy, and this landscape may be evidence of their trip. It is also a very special work because of the way the subject is approached, with fishermen returning from the beach after their work and their beached boats waiting to set sail again the next day. The relationship between man and nature almost seems to anticipate the seventeenth-century sublime. Also of note from Caretto & Occhinegro is a Wooded Landscape with Gospel Episode by David Vinckboons and a particular Study of Insects with Borage Flower by Jan van Kessel the Elder.

|

| Roelant Savery and Hans Savery II, Coastal Landscape with Fishermen in Front of a Saracen Tower (1613-1614; oil on circular panel, diameter 49.5 cm) |

6. Giovanni Lanfranco, Madonna and Child with Two Angels (ca. 1615), submitted by Galleria Megna

Given until recently as an eighteenth-century French work, this small Madonna and Child with Two Angels, an oil on copper, is presented with a new and very high attribution, namely, it is assigned to Giovanni Lanfranco (Parma, 1582 - Rome, 1647). Author of the attribution is an expert on the Parma painter, Erich Schleier, who in a small publication devoted to this work formulates Lanfranco’s name on the basis of a number of comparisons, including theAdoration of the Shepherds in the Chigi Collection and the Nativity in Alnwick Castle. Above all, however, Schleier believes that this work derives from a lost painting by Lanfranco and known only through copies, the so-called Night X, of which the Madonna and Child with Two Angels seems “a partial derivation,” especially “with regard to the general layout of the composition.” The work should be dated to a period close to 1615, when Lanfranco produced several oils on copper.

|

| Giovanni Lanfranco, Madonna and Child with Two Angels (ca. 1615; oil on plots, 16 x 21 cm) |

7. Antiveduto Gramatica, Apollo and the Muses (ca. 1620-1626), submitted by Robilant + Voena

Another work among the best of those to be seen at the BIAF,Apollo and the Muses (also known as Parnassus) is a work that can be ascribed to the last phase of the production of Antiveduto Gramatica (Rome or Siena, c. 1570 - Rome, 1626), an artist who was among the first to incorporate the new stylistic features of seventeenth-century realism, although he always remained attached to the formal elegance that had characterized his training. For a brief time, moreover, Gramatica was also a master of Caravaggio. TheApollo and the Muses (the god is in the center while, with rapt gaze, playing the zither) is a typical example of his lesson. Robilant + Voena’s other proposals at the BIAF are also worth seeing: a valuable Saint Jerome by Orazio Gentileschi stands out above them all.

|

| Antiveduto Gramatica, Apollo and the Muses (ca. 1620-1626; oil on canvas, 152 x 172 cm) |

8. Canaletto, Church of the Redeemer (ca. 1746), presented by Dickinson

The London gallery Dickinson, another new entry at BIAF, is presented with some interesting Vedutist works, including this important Church of the Redeemer by Giovanni Antonio Canal, better known as il Canaletto (Venice, 1697 - 1768). This is a work that the Venetian artist probably executed for the English market (that is where he resurfaced in the mid-19th century), and it is an exemplary work that allows us to fully grasp the artist’s poetics, balanced “between spatial verisimilitude and atmospheric sensitivity , while admitting all the technicalities of the camera ottica” (so Fabrizio Magani in the article in the third issue of our print magazine in which Canaletto and Francesco Guardi are discussed and this important view of the Venetian church of the Redeemer is also described).

|

| Canaletto, Church of the Redeemer (ca. 1746; oil on canvas, 47.4 x 77.3 cm) |

9. Andrea Appiani, The Myth of Europa (ca. 1784-1786), presented by Galleria Carlo Virgilio & C.

Galleria Carlo Virgilio & C. brings to the BIAF four large canvases by Andrea Appiani (Milan, 1754 - 1817), which narrate the Myth of Europa through four episodes: Europa’s companions swallowing the bull, Europa sitting on the bull’s back, Europa abducted by the bull crossing the waves, and Europa consoled by Venus presenting her with love. For a long period of time the four canvases belonged to a Milanese nobleman, Count Ercole Silva, but there is no precise information on who the original commissioner was (long believed to be Silva himself, although the hypothesis has been questioned in a publication presented on the very occasion of this edition of BIAF). Works well known even to 19th-century critics, they represent one of the high points of Appiani’s production.

|

| Andrea Appiani, Scenes from The Myth of Europa (c. 1784-1786; tempera on canvas, each 190 x 135 cm) |

10. Angelo Morbelli, The Bride (1909), submitted by Enrico Gallerie

On the centenary of the death of Angelo Morbelli (Alessandria, 1853 - Milan, 1919), Enrico Galleries are offering an interesting selection of his works in their booth, including the first version of The Bride, a delicate painting from his late production, at a time when works centered on the human figure are quite recurrent in the art of the Piedmont-born painter. In this version, the young woman, dressed in a wedding dress, is praying in a bare interior, with a small floral bouquet in front of her: later, Morbelli would paint the same subject but set, inside a church. The Enrico galleries’ booth also features other interesting offerings, including a wonderful female portrait by Antonio Mancini and an unusual �? la campagne by Giovanni Boldini, an early work by the artist.

|

| Angelo Morbelli, The Bride (1909; oil on canvas, 71.5 x 57.5 cm) |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.