What can art do in the face of war? At first glance I would feel like rephrasing the question into what, in the face of the current scenario, we, all of us, could or should do. Evidently little, even where a civilian consciousness makes its presence felt in various ways, up to the recent, at least in Italy, but already quite widespread establishment of PhDs in peace study. Affecting the field of international sciences, these are paths of study dictated by several reasons, including that of knowing and deepening the role entrusted precisely to culture and art as a vehicle, particularly after World War II, of diplomatic and political strategies for a regained identity of individual states (more so the defeated ones) up to and including the ideal goal of prefiguring a different way of inhabiting the world. Certainly ideal, if conflicts, it is known, have not stopped running through it, and, after an apparent pause, have today resurfaced in the interests of a geopolitics that plays, cynically and unscrupulously, its cards. Wars before which we live, with the accelerations of our daily lives, as helpless if not addicted spectators to the horrors that come our way.

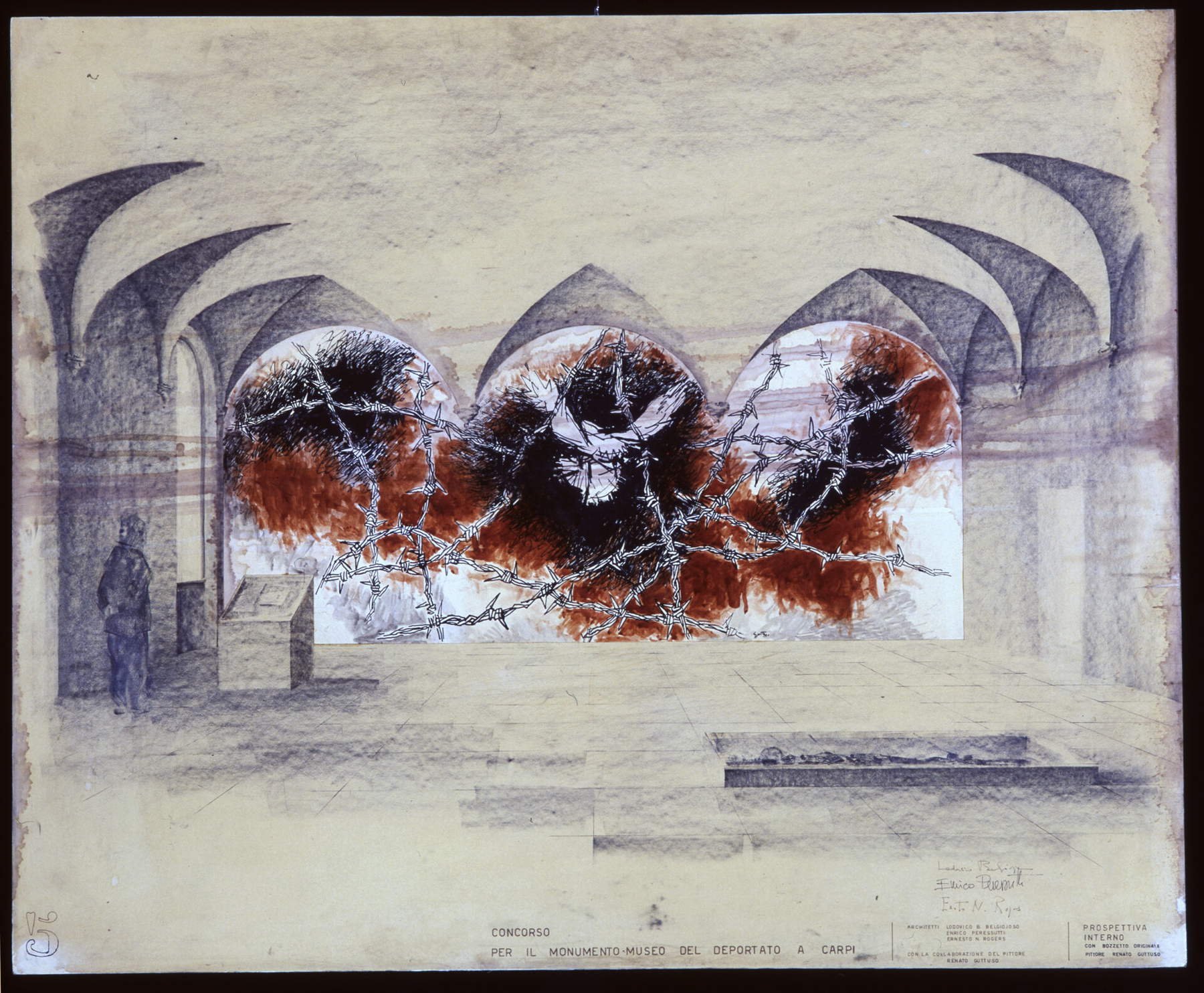

But let us return to art, which in all its expressions, from visual arts to literature to music, holds that singular aura to which we are attracted by receiving from it emotions, openings to other horizons, pleasure in beauty but, also, unveiling the ugliness of the world. An involvement with respect to such forms of expression of which history boasts many examples especially along the short century traversed by the two great conflicts, struggles against totalitarian regimes and anticolonial resistance. In such a framework, contemporary art has often raised its voice and, for those who teach the history of that discipline, it is not unusual to find themselves talking about it with their students, addressing content and forms that have given substance to a commitment that in addition to being civil has been, and still is, moral. They are worth, in extreme synthesis, the apocalyptic and grotesque ’writings’ of the expressionists of the German area and, par excellence, Picasso’s Guernica manifesto capable of engraving with the force of the symbol on the consciences of a Europe that, traversed by the Nazi-fascist regimes, would shortly know even darker pages. It is in this phase of history that the commitment of so many artists in Europe and Italy to bear witness to their human and political position is located. I myself was curator (with Lorenza Roversi) last year of an exhibition celebrating the fiftieth anniversary of the birth of the Museum of the Political and Racial Deportee in Carpi. It was an exhibition that, starting from the pages engraved on the interior walls by artists such as Guttuso, Leger, Picasso, Longoni, and Cagli, took stock of that architecture, a true monumentum (remembrance and warning) designed by the BBPR studio in Milan in the early 1960s (inaugurated only in 1973), but above all of the educational value of ’art in society and history, bringing on stage, in addition to those mentioned above, artists such as Aldo Carpi, Vedova, Morlotti, Levi, Garelli, Mirko, Manzù, Treccani and others. It is just a reminder, among excellent and previous exhibition initiatives on the theme, aimed at emphasizing how much the datum of memory, outside of sterile rhetoric, is matter to be cultivated to give meaning, if it still has it, to a possible future. I have often seen on the faces of the young people with whom I find myself talking about such experiences and the languages adopted by the individual protagonists, draw expressions of interest that, overcoming the usual reluctance, spurred them to a dialogue on how much and how such participation had affected the state of things, if not contributed to changing them.

To tell them, following my own thinking, that art reflects, witnesses, sobers, not infrequently provokes, but does not change the world or the course of things manifested in it, seemed until recently to find them sufficiently inclined to accept the suggestion of a confidence in ideas and models of reference.

A trust that seems to have thinned out since, beginning with the estranging COVID caesura to the onset of today’s wars, their relationship with the present has been reshaped toward new channels of confrontation, of more immediate, ’easy’ grasp in the paradigm of communication. It is not a phenomenon, of course, that affects only young people, but they undoubtedly constitute a fertile observatory both for questioning the changes and drifts of the reality in which we are immersed, and for trying to understand how much the language of art, its communicative reach, is able to affect the public, even there where media and technologies seem to have shifted the axis of the balance in their favor. I do not believe, however, that art has lost its strength or surrendered its imaginative energy to the indiscriminate advance of ’reality effects’ from sources that have grown out of all proportion in the communications production industry, which is, after all, no stranger to art in its being part of the present. Its role, however, is to draw diversified perspectives to our gaze, to dig furrows that leave traces of its own feeling, to rise above the obviousness, banality, homologation, bad taste, and empty visibility of content, of which there is no shortage of traces, either.

I am thinking of the case of Dennis A. Jose who, in an almost pop transcription, replicated, at the time of the sad affair of Abu Ghraib, one of the most media and legally imposed images, namely that of the soldier Lynndie England intent on pointing a gun at Iraqi prisoners, physically and psychologically humiliated. An exclusively formal sampling that eluded any possibility of critical reading and semantic repositioning of the photographic image, as was the case in Errol Morris’ documentary Standard Operating Procedure. The Truth of Horror released in 2008. It is one of the many uses of images that a conspicuous literature related to the field of visual studies has long been concerned with precisely to analyze their value, use, power, and effects in history. This is not the place to deal with that. So returning to the input launched by these pages, I feel I can say that art has not lost solidity, especially when it continues to move within the framework of its own status. The list of artists working in this direction could be very long. I try, for the sake of synthesis, to make two of them as distinct faces of a common feeling. I refer, on the one hand, to the Italian Paolo Grassino for the work War is Always 2019 set up in the naturalistic area of Scultura in Campo, International Sculpture Park in Bassano in Teverina (Viterbo). A monolith proposed as a tombstone, strong visually in telling and reminding us, with the dates and territories engraved in stone, the massacres and rubble marked by invisibility destined, in some cases, to the mere consumptive of consummate rituals. On the other to the long experience of the Iranian, now living in Japan, Hossein Golba who, for years, has been building his works on the principles of spirituality and conviviality by resorting to symbolism and poetry. Works in which, from the Sculpting Time cycle of the early 1990s to subsequent environmental interventions, including Landscape Haiku and the 2006 Community Table, he shares a silent dialogue that speaks of love, beauty, and care. May these be the paths that art can still show us?

This contribution was originally published in No. 27 of our print magazine Finestre Sull’Arte on Paper, erroneously in abridged form. Click here to subscribe.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.