An exhibition on Banksy has been circulating for some time now that invites visitors to decide whether the anonymous Bristol street artist is a genius or a vandal: that, at least, is the question the title of the exhibition poses to its audience. A question as Manichean as it is rhetorical, of course: the mere fact that the exhibition presents Banksy as "one of the greatest exponents of contemporary street art “ and that, in the words of the organizer, ”the exhibition seeks to reveal the depth of Banksy’s extraordinary talent," is hardly a good start to avoid conditioning visitors on the question at hand. The discourse applies to all the exhibitions on Banksy that have been furore in recent times and are spreading like wildfire all over the world (one can no longer count, even in Italy, the reviews that are dedicated to him). Always the same cliché: barrage of silkscreens from private collections, posters with the usual two or three icons (the little girl with the balloon or the Flower thrower) to grab the public, total absence of works by other artists to ensure a minimum of context, uncritical celebrations devoid of contradiction. And museums that, when it comes to Banksy, often temporarily suspend their mission, which if we are talking about contemporary art should consist in critically reading and ordering the productions of the present (perhaps with a little scientific approach), and on the contrary do everything that a museum should not do, that is, they simply pander to the prevailing taste, feed the public what the public wants and expects, join the chorus of rapturous praise extolling a likeable cartoonist who has become a genius by popular acclaim.

What escapes most, however, is that criticism and art history are not done with an applause meter, and that any artistic phenomenon should be studied in relation to its context and what preceded it. Thus, if one were to widen one’s gaze for a moment and try to understand what Banksy really is, then some solid certainty might begin to waver. Banksy’s innumerable admirers hold similar positions to those that Tomaso Montanari expressed in an article published in Venerdì di Repubblica on November 30, 2018: "net of the cloud of fake news that surrounds him, his ambiguous relations with the market, and the ingenious direction of his anonymity, there is no doubt that Banksy is a great artist of our times. Probably the most capable of translating the desire for revolution into images: the need to turn a monstrously unjust world upside down from the ground up." The resounding qui pro quo into which almost all those who consider Banksy one of the most significant contemporary artists fall lies in mistaking his extreme popularity for greatness, assuming that to consider Banksy a “great artist” means to mean that he has produced something truly innovative or revolutionary, such as to consign his name to that of art history, going so far as to include him already in school textbooks (as Irene Baldriga did in her Inside Art). If Montanari’s words, from “probably” onward, were used for music instead of art, they would be perfect to describe, for example, a singer like Jovanotti: the extreme vagueness of the statement and the lack of framing, after all, pertain more to the sphere of the fan’s unconditional admiration than to the critic’s detachment.

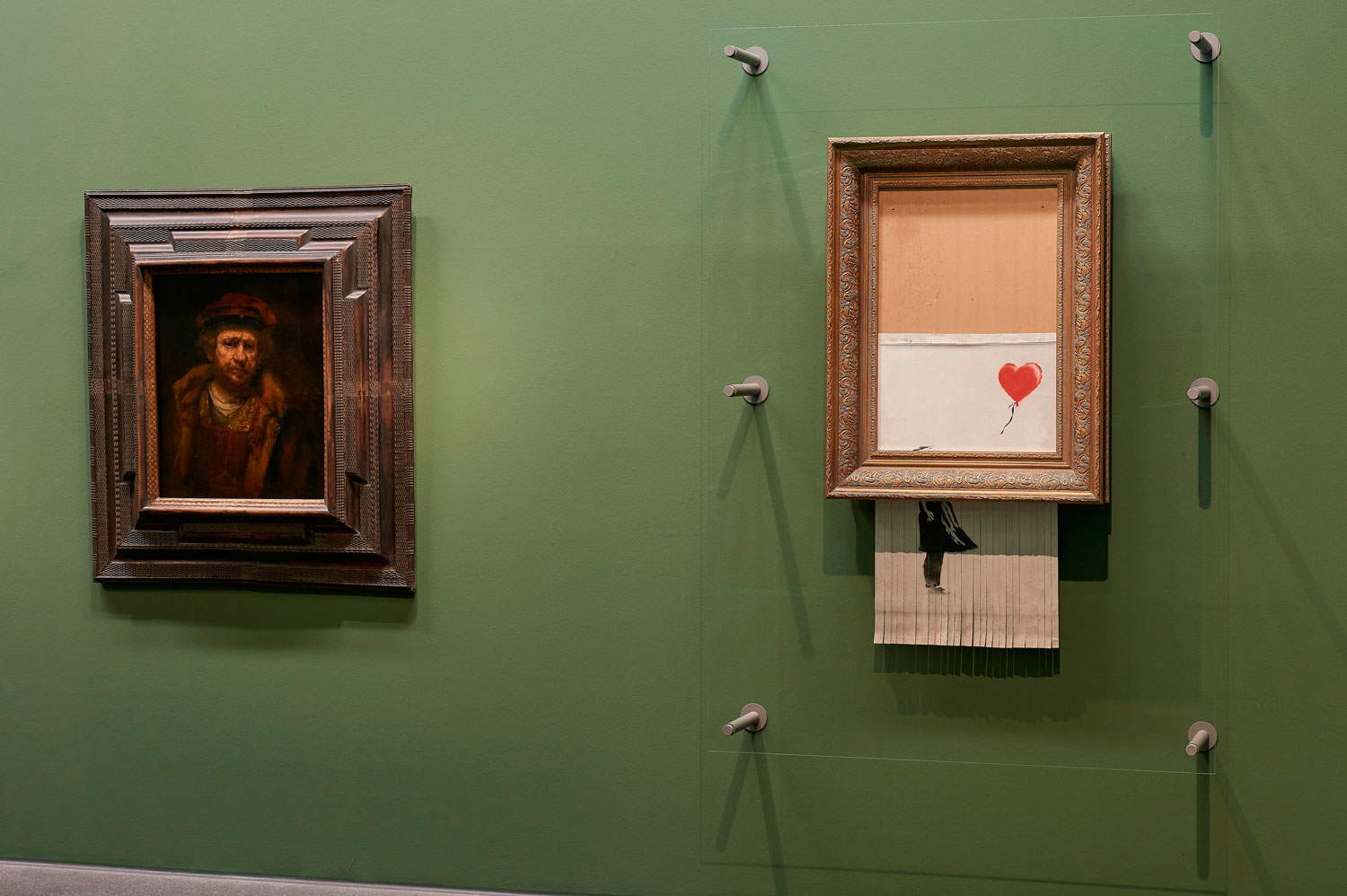

The problem, however, is that while no one would dream of including Jovanotti in a musical canon that also contemplates Vivaldi, Robert Johnson, and the Velvet Underground, it is perfectly normal for Banksy to be juxtaposed with impunity with Raphael, Rembrandt, or Warhol (just to name three artists alongside whom the Bristol-based street artist has actually been exhibited). Normal, and totally understandable: on the part of museums, because exhibiting Banksy’s works guarantees an immediate public return that does not involve a heavy commitment (just put together a few multiples). On the part of the public and the fans (including those who write in the newspapers), because if you have never seen a work by John Fekner, Blek le Rat or Nick Walker, if you have never leafed through an issue of Frigidaire, if you have never set foot in a contemporary art fair, and if you forget for a moment that Italy is the country of Pietro Aretino and Gabriele Galantara (but Daniele Luttazzi is fine too), then Banksy will also seem like a giant to you. Which is not the case with Jovanotti, because if few have seen a work by Blek le Rat, on the contrary many will have heard, if only by hearsay, of Area or the Clash. It should also be stressed, however, that one does not accuse Banksy of being less of an artist than others just because his work is merely epigonal (in which case we should erase perhaps most of the history of art), nor even because he is a perpetually late artist (the sneering at Queen Elizabeth twenty years after the Sex Pistols, the Kissing Cops five years after George Michael, the monkeys in Parliament one hundred years after Gabriel von Max), since lateness in art is entirely legitimate and not a fault (indeed, sometimes a refresh is healthy, positive, and necessary, and even one hundred years after von Max the monkeys can still say something). Rather, Banksy is a “dull and culturally irrelevant buffoon,” as Jason Farago called him in the New York Times, not only because his social denunciation is scarcely credible (of this Farago accused him, contrasting his example with that of Maurizio Cattelan, whose banana criticized the system from within: just think of the antics of Banksy’s canvas being destroyed at Sotheby’s), but also because his works are extremely banal. Or “utterly conventional,” if one wants to use the adjective that Jerry Saltz has saddled him with.

|

| Banksy exhibited next to Rembrandt at the Staatsgalerie in Stuttgart. |

They are trivial because they are mediocre, and they are mediocre because, if you want to meet the tastes of a cross-sectional, global audience, you have to lower the bar to the limit of facile. At least that is what Tommaso Labranca thought when he wrote that “to please millions of people who are different from each other and who live in Latin America or the Baltic republics, you have to act as in statistics: add up all the characteristics and derive an average. It is this search for the average that makes the product mediocre. The public wants music that does not have local references, which are considered obsolete and folkloric, that is danceable, that has repetitive and anodyne lyrics in which they can recognize their own little love experiences.” The same reasoning applies fittingly to Banksy: in order to reach more people, the British graffiti artist can do nothing but continually invent school assembly slogans that stop at the surface and are extremely boring and predictable (as well as harmless). Especially now that he has started posting his gimmicks on Instagram for the designated holidays, whether religious (Santa’s sleigh with the clochard), commercial (the mural for Valentine’s Day the day before yesterday) or secular (his foray into the Venice Biennale last year, which everyone had already forgotten about two days later).

To make the concept clearer, take Girl with balloon, perhaps his most famous work, and certainly the most obvious example of Banksy’s ready-made sentimentality: the effect of this work, Jonathan Jones wrote three years ago, “is to brutally reduce human emotion to crudeness and obviousness. Instead of portraying a human being rich in elusive emotions, Banksy gives us a one-dimensional icon whose pathos is instantly readable.” There are no different levels of interpretation, no complexity, no deep readings: Banksy’s populist slogan (populist because it is anti-Helitist, because it seeks consensus and because it seeks to legitimize itself on the basis of consensus, because it does not allow for nuance, because it is an icastic image of the postmodern depthlessness that Jameson spoke of) always comes across as direct and unintelligible (so much so that Girl with balloon was declared the most beloved work by the people of the United Kingdom following a YouGov poll in 2017). And it is for this reason that it breaks through. This is why, every time he posts an image on his Instagram profile, it triggers the conditioned reflex of the media (including us: in the editorial staff on the attention to be given to Banksy we have opposing opinions) who start chasing him and competing to see who can be the first to post his latest release. That is why when comparisons with Cattelan or others start, more often than not Banksy is the genius and Cattelan is the artist who mocks the public. This is why his sloppier images have overshadowed his few glimmers of audacity, the rare times when Banksy has been capable of some good ideas and some interesting insights (such as when in 2013 in New York he came up with a cattle truck full of stuffed animals to get some animalistic content across: nothing particularly original, but certainly better than his fast food icons of art). Not to mention that, in keeping with the good tradition of all phenomena that can be categorized in the realm of aesthetic populism, Banksy is also liked by those in politics who are anti-populist.

Of course: there is nothing illegitimate about the adoration of the masses for Banksy, nor is it of concern that Banksy draws crowds wherever he is exhibited: each audience has its own art and it is right that it should. What is of concern, if anything, is the attitude of those who are supposed to make order and end up putting Banksy on the same level as Rembrandt because he is incapable of opposing the “like” regime. And forgets that “there is no possibility of voting on aesthetic judgment” (so Emilio Isgrò reminds us), and that art history is not written with “likes.” Otherwise, if Banksy’s art has to find a legitimacy that can make him rise to a level that does not belong to him, it will be convenient to establish that, from now on, a work of art simply has to be pretty in order to boast of setting a canon.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.