On November 30, the “Manifesto on Cultural Rights and Duties,” promoted by the Democratic Party, was presented in Palermo at the Palazzo dei Normanni and the Salinas Archaeological Museum. The aim of the document is “the recognition, protection and respect of the cultural rights and duties of individuals and communities and is intended to be a tool to create and increase awareness of them in the community: institutions, businesses, civil society.” An end that is intended to be achieved, the document goes on to say, through the “drafting of the Charter of Cultural Rights that proposes the establishment of the figure of the Guarantor.” As for the legal foundations, “the Manifesto refers to specific normative sources and identifies those rights and duties that fall within the category of cultural rights.” In reality, this “reference to specific normative sources,” translates into a generic identification in “documents of international law, European Community law, in the Italian Constitution, in ordinary laws, in regional laws, in regulations, in customs and traditions.” Perhaps, a timely recognition is postponed precisely to the drafting of the Charter.

Thus, “cultural rights” are defined: “inalienable rights that every human being possesses. They are universal, indivisible and interdependent with other human rights. They are indispensable to the dignity and free development of the personality of individuals, to peaceful coexistence and are based on the existence and recognition of cultural diversities and pluralities.” A listing of them follows: “the rights of opinion such as freedom of thought, knowledge, religion, expression; the right to the protection and preservation of the tangible and intangible cultural heritage, the landscape of the communities to which they belong; the right to the creation, dissemination and participatory enjoyment of cultural expressions; the right to lifelong education and training; the right to research, produce, transmit and receive information; the right to the protection of moral and material interests related to the works that are the fruit of one’s creative activity.”

As for “cultural duties,” which “express the moral obligation and individual and collective responsibilities to foster respect for them,” only one is identified, however, that of “devoting resources to ensure the exercise of cultural rights, guaranteeing those who invoke their violation access to effective remedies.”

Summing up: the effort, which is commendable (a sort of declaration of intent for a “single text” bringing together the utterances delivered to various documents of national and supranational law), misses the mark, however, on a hot topic, that of the right to the recognition of professional dignity in this field. That is, the right to work in cultural heritage. Paid: it is worth pointing this out, given the not unusual overlap between labor and volunteer work. As it is worth recalling, speaking of sources of law, Article 4 of the Constitution, among its fundamental principles: “The Republic recognizes the right of all citizens to work and promotes the conditions that make this right effective. Every citizen has the duty to perform, according to his ability and choice, an activity or function that contributes to the material or spiritual progress of society.” It is to be hoped, then, that this constitutional right may rightfully fall ... within the themes of the future Charter.

Otherwise, the meaning of this Manifesto would be diluted in its being, as Giuliano Volpe points out, little more than the transposition of principles already enunciated in the Faro Convention. Incidentally, in his blog on Huffpost, the former president of the MiC’s Consiglio superiore Beni culturali e paesaggistici, who spoke at the presentation of the Manifesto in Palermo, stresses, in line with the Sicilian primacy claimed in the document, the historical and cultural reasons why the latter sees the light precisely in Sicily and not elsewhere in Italy: because it is here that “new formulas for the protection and enhancement of cultural heritage were experimented,” he writes, “with the adoption of single superintendencies or with the law on archaeological parks.” Except to add in parentheses, “although then, more recently, those important innovations have known very unconvincing applications, also due to a persistent mortification of professional skills.” All agreeable, were it not for a not venial contradiction, given that Volpe himself has made no small contribution to those “very unconvincing applications,” participating as a member of the Regional Council of Cultural Heritage (“homologue” of the MiC’s Superior Council), at the January 30, 2018 session by which the Musumeci government in Sicily gave the okay in one fell swoop to as many as 15 archaeological parks, while the regional law provides for the acquisition of individual opinions by the advisory body. What came out of that “sit-down” we recounted in a lengthy investigation in these columns. In short, we could say, to use Volpe’s own words, that it has been the “cause of a persistent mortification of professional competence,” since in these parks it is provided that political administrators such as mayors can express themselves in place of “technicians,” archaeologists in the lead, on matters also pertaining to protection. But, then, why precisely in the land of Sicily and with these precedents in the recent history of the Sicilian cultural heritage, did the archaeologist not speak in Palermo in the guise of a member of the Regional Council, instead of in the “distant” guise of former president of the Superior Council, in which he appears in the press release, in the invitations, both at Palazzo dei Normanni and at Salinas and in press articles? Why this “damnatio memoriae”? Actually, not the only oddity of that day (see Box).

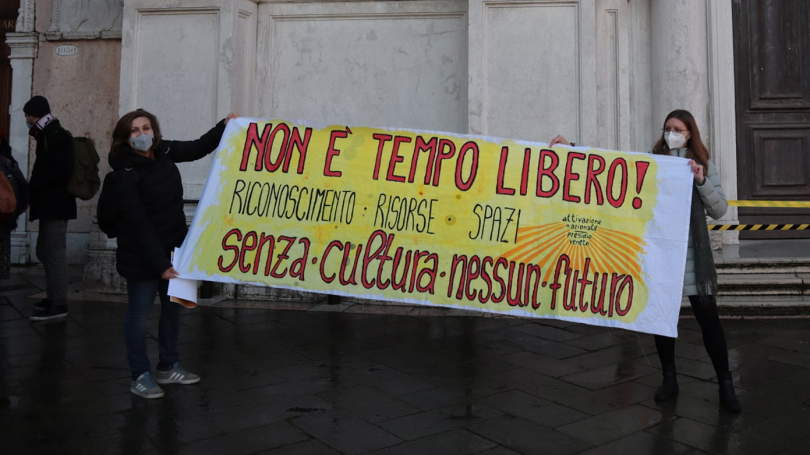

Let us return, instead, to the heart of the matter: the recognition of professional dignity in a sector where there are “caporalato wages from the plain of Sibari.” The expression is not from some trade unionist, but from the president of Confindustria Messina, Ivo Blandina, at the presentation (after the Chamber of Deputies) in November 2019, promoted by the writer, at the Regional Museum of Messina,of the survey of “Do you recognize me? I’m a Cultural Heritage Professional,” which photographed the gloomy picture for those working in the sector. It emerged that 80 percent of participants earned less than 15 thousand euros a year and with salaries of less than 8 euros per hour declared by half of the respondents. Situation dramatically worsened in Covid time, as photographed by a new survey by the Movement, which returned the situation, one year after the first lockdown, of women and men cultural workers. Work in the cultural heritage sector is not enough to live on. This is the sad reality that clashes with the principle that every citizen has the right to culture. It cannot be forgotten, even in a theoretical statement such as that of a “manifesto.”

The issue of the irrelevance of “human capital” goes hand in hand with that of its instrumentalization, the other side of the coin of a denied professional dignity. Several controversies have been stirred up by the 28 appointments without competition of new heads of various MiC institutes, including a parliamentary question. In fact, it seems obvious to say that the awarding of appointments through the act of interpellation, which is a para-competitive procedure or internal competition, for those who have already entered the ranks of the administration through competition, does not take place in violation of the regulations. Not even if they are officials “elevated” to managerial rank, as stigmatized, on the other hand, in the aforementioned question for which it would be in the Franceschini era that “for the first time that decisive career progression took place without having to face any test.” In 2012, in fact, the Lazio Court of Auditors, in its deliberation on the legitimacy of two measures for the assignment of executive functions when minister Lorenzo Ornaghi (Monti government) was minister, did not record the positions awarded (one of the two was by an official himself) because of the illegitimacy of the interpellation procedure, a comparative selection of curricula in which work experience, skills and positions held must be taken into account, as governed by d. lgs. no. 165/2001, but for the “violation and false application of the regulations in force,” “the violation under the profile of excess of power (manifest illogicality).” In short, a selection masked by the logic of political affiliation.

In a press release at the time, the UIL-BACT National Secretariat commented with satisfaction that “the court by not recording the assignments made (...) by the Director in charge of the Regional Directorate for Cultural and Landscape Heritage for Lazio marked an important point in the correct application of the rules.”

So, Administrations, the MiC as well as the Sicilian Region, are obliged to give adequate reasons with respect to the choices that are made. Although these are, in fact, discretionary choices, they must be anchored in evaluative elements that are as objective as possible, such that they can be verified with reference to the actual pursuit of the public interest at stake. But also in such a way as to give candidates the opportunity to know the reasons for the choices made.

From Sicily, which should be exporting good practices in the state sphere, according to the good intentions of the PD Manifesto, these comparative selections are completely superseded precisely in the appointment of directors of archaeological parks, which take place by designation of the Assessore dei Beni Culturali in person. In other words, here we cut short even with the appearances still made for appointments to head museums and superintendencies, which are made by the Regional Executive, i.e., the top administrative leadership, and not by the political leadership.

Therefore, it is not the selection procedures through interpellation in accordance with the law, or the new “formula” of the course-competition for the recruitment of executives to the MiC, that is the raw nerve of the matter, but a country that goes on from north to south according to the logic of political interest groupings that wallow in the sea of discretionary appointments. For that matter, in the same country of rigged university competitions denounced by Sicilian researcher Giambattista Scirè, founder of the Transparency and Merit Association, in his book “Mala università: Baronial privileges, mismanagement, rigged competitions. The cases and the stories” (Chiarelettere), one cannot understand the fideistic hope in public competitions, in lieu of interpellations in the dock, to which those outraged by recent MiC appointments have surrendered.

A little yellow on the sidelines: but does the Manifesto presented in Palermo bear or does it not bear the signature of the PD? In the document, in fact, there is no trace of the party’s logo, and the preface reads only that “it was born from a dialogue, over time, between Manlio Mele and Monica Amari and was elaborated by a group of scholars in cultural policies and processes from different fields and experiences.” These include, in fact, some members of the Culture Department Democratic Party of Sicily. It is not specified in the document, but Manlio Mele himself is the head of the Department. At the bottom, then, there is a list of signatories, but in fact it is not clear who actually signed the text, since surely the president of Legambiente Sicilia, Gianfranco Zanna, did not do so and even warned to remove his signature that instead appears on the document. In the list jumps out the absence of the director of the Salinas, Caterina Greco, who on her Facebook page (“Caterina Greco - Salinas”) does not post anything about the event. While on November 29 on the museum’s official page, the presentation of the Manifesto of the next day is announced in a “neutral” key: no logo, not even in the invitation, nothing that highlights the political authorship of the initiative. Thus it is also explained, for example, that the first of the institutional greetings listed on the invitation is that of the Regional Minister of Cultural Heritage, Alberto Samona, of the League. But how? At a PD event?! And, in fact, on the Assessor’s Facebook page there is no trace of it. Fact is, “the show must go on,” and in a post by the Archeologico the next day we read, “The manifesto on the rights and duties of cultural heritage in the light of the Faro Convention starts from Sicily: a crucial issue for the growth of people and the sustainable development of society. We thank the authoritative speakers for their proposed reflections.” Despite this recognized relevance and the absence (on the surface) of political connotation, the director had not, however, signed the Manifesto. It is only in the press release that things regain their proper name: the logo of PD Sicily to dispel any misunderstanding and promoter of the Manifesto the Cultural Heritage Department of the Democratic Party with the statements of its head Mele. Is there an explanation? Let’s try asking a question I formulated on July 6 in the newspaper Gazzetta del Sud: can cultural heritage assets, monumental buildings or archaeological areas, subject to protection be turned into locations for political events? On June 26 at the Church of the Spasimo in Palermo, a convention on the three years of the Musumeci government had been held. Among the speeches was that of Councillor Samonà. The year before, it was July 18, the use of the Morgantina archaeological site for the PD congress that led to the election of new secretary Anthony Barbagallo had sent Samonà himself into a rage. A circular had thus narrowly arrived, expressly forbidding “initiatives by political parties and movements” at cultural sites. The properties affected are exclusively those in the hands of the regional department, while the Spasimo is owned by the municipality, but still under the supervision of the Superintendence for monumental constraint. Beyond ownership, the substance does not change: for this government, are events of a political nature or not “purposes compatible with the cultural destination” of the property as required by the Cultural Heritage Code? Can the showcase of the Musumeci government be considered a “purpose of use” compatible “with the historical-artistic character of the property itself” as the same normative dictate also prescribes? Or are we facing the classic case of double standards and the prohibition applies only to oppositions? In our case at Salinas the matter is a little different. Despite the scrupulous observance of the regional circular that would explain the singular, not to say bungled “censorship” in which the PD ended up with its Manifesto, in fact the ban was contravened. There is, however, to be considered an open debate. We believe, in fact, that the PD’s event is in accordance with the superior state law, which also applies in the Special Statute Region with primary legislative competence. The Cultural Heritage Code, which is superordinate to an aldermanic decree, requires in Article 106, Paragraph 1, that the purposes of the concession for the use of a cultural asset, in this case a museum, be compatible with the cultural destination of the asset itself, and in Paragraph 2-bis that the compatibility of the destination of use with its historical-artistic character be ensured. These are all requirements in continuity with the presentation of a Manifesto of Intent in favor of cultural heritage. To be clear, it is one thing for the showcase of the Musumeci government in which the Councillor for Cultural Heritage tramples on his own circular, it is another for a party not to use a museum for propaganda purposes but to speak to civil society about “cultural rights and duties.” Albeit with the gaps that we hope will be filled in the drafting of the Charter.

The author of this article: Silvia Mazza

Storica dell’arte e giornalista, scrive su “Il Giornale dell’Arte”, “Il Giornale dell’Architettura” e “The Art Newspaper”. Le sue inchieste sono state citate dal “Corriere della Sera” e dal compianto Folco Quilici nel suo ultimo libro Tutt'attorno la Sicilia: Un'avventura di mare (Utet, Torino 2017). Come opinionista specializzata interviene spesso sulla stampa siciliana (“Gazzetta del Sud”, “Il Giornale di Sicilia”, “La Sicilia”, etc.). Dal 2006 al 2012 è stata corrispondente per il quotidiano “America Oggi” (New Jersey), titolare della rubrica di “Arte e Cultura” del magazine domenicale “Oggi 7”. Con un diploma di Specializzazione in Storia dell’Arte Medievale e Moderna, ha una formazione specifica nel campo della conservazione del patrimonio culturale (Carta del Rischio).Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.