The narrative of the ongoing health emergency has developed, with continuous and constant vehemence, mainly around the work of those who have been identified as the “front lines” of the war on the coronavirus, namely the doctors, nurses and, in general, all the staff working in hospitals, ambulatorsî and health facilities, to whom all our gratitude goes for the invaluable work that, with a great sense of sacrifice, they are doing for the benefit of the community (and hopefully their spirit of dedication, when the alarm is over, will be the basis for serious and prolonged reflection on the needs of our national health system). Our newspaper is concerned with art and culture, and I would like to open a discussion also on what, to continue with the wartime comparison (admittedly rather obnoxious, but nonetheless widespread and effective), we could identify as the “second lines,” that is, those professionals who are taking care not of those who need treatment, hospitalization and care, but of all those who remain at home, forced by this long, forced home isolation, which for some moreover we imagine will be anything but easy and harmless.

The thought, as one would naturally expect, runs to the diverse “world of culture.” Perhaps, never as in these days has what was until now a paradigm clear to a few become almost a public awareness, namely the fact that culture is fundamental to our lives and that culture is the basis of the sense of community of a more or less large group of individuals. Put another way: without culture we cannot live. And I believe that these days have fully demonstrated this: in case of urgency, it is possible to give up many of our daily activities, but probably no one would give up reading a book, exercising their right to inform themselves, listening to a song, or even more trivially turning on the television to watch a movie or scrolling through the pages of a social network to continue to keep in touch with their favorite artist, with a museum they would like to visit, with the theater they attend or would like to attend. And this does not happen because it is necessary to find a filler to so many days that have suddenly lengthened, but because, as Gastone Novelli put it, art, like science, is one of the ways in which human beings orient themselves in the world, and consequently we can say that it becomes all the more important the more one is liable to lose one’s bearings, even if only for a short while.

We will have time to assess how this emergency will have impacted on our cultural habits, on what culture is proposed to us by the mass media and on the ways in which it is distributed to us by the national networks (take, for example, the curious prêt-à-porter patriotism exhumed in the last few hours and become a must-have for television and the generalist press: it will be interesting to understand whether it will have had the same duration and effects as World Cup homeland love, whether it will have served to generate at least a more pronounced, more conscious and more pressing sense of civic duty, of which, moreover, we have an enormous need, or whether, at worst, it will feed a nationalism that could risk becoming a pathogen more dangerous and harmful than the virus). Some consequences can already be observed, however, and useful insights can be drawn from them.

For many of us, the compulsory quasi-quarantine regime has not lowered workloads, nor has it increased the amount of free time. Far from it: just think of the hundreds of cultural workers who, from the Brenner Pass to the Sicilian Channel, had to attend accelerated web and social training sessions to make sure that their institutions (museums, archaeological parks, libraries, theaters, cinemas) did not lose contact with the public and, vice versa, to make the public feel their closeness. Here, too, there will be room to discuss the sector’s chronic lag and the fact that few museums were already prepared to deal with the Internet public, the officials accustomed to pen and inkwell who wanted to and had to rediscover themselves as social media managers overnight, the fact that, for some, communicating on social perhaps amounts to replaying on YouTube a university lecture exactly as it would have been conducted in “analog” mode. For now, I think we should be more than proud of how our sector, with museums in the lead, has responded to this sudden crisis: it must be acknowledged that for many it has not been easy to invent from scratch a communication campaign on social, to identify the audience, to devise an efficient strategy to reach them, to figure out how to organize content according to the different media. But many have tried, and perhaps everyone has finally recognized the importance of digital: the hope is that this experience will not be resolved in the way that the many “museum weeks” on the various Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram are typically resolved, which usually consist of a continuous, and without ideas, “posting” of unhelpful photographs and videos, made only to show that the museum is present. On the contrary: the emergency will have to lead museums to equip themselves with long-term communication plans that take into serious consideration their eventual sustainability (what will happen to the dozens of hashtags launched in the last few hours when the operators go back to doing their usual work? Let’s sincerely hope that the experience does not run out!), that manage to ensure that the enlargement of the public experienced in these days does not remain a temporary flare-up, but translates into a wider and, above all, more aware public when we can finally get out of the house again.

|

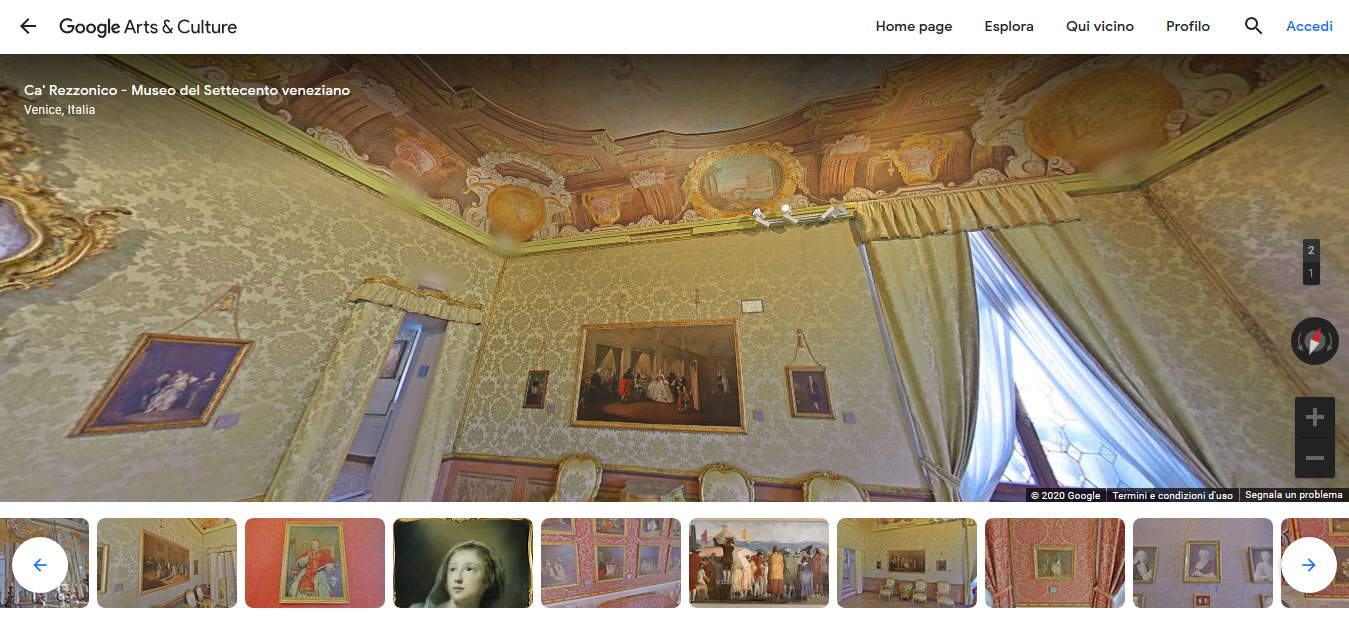

| The Museum of the Venetian Eighteenth Century at Ca’ Rezzonico on Google Arts. |

Thinking about audiences is one of the keys to getting out of the emergency faster. Museums, theaters, exhibition spaces, concert halls, and cinemas will open again before long: the experience we have gone through these days will have to be the basis for boosting cultural participation. Indeed: we need to ask ourselves right now how to make sure that the public returns to populate, and indeed that it returns to populate even more copiously and even more wholeheartedly, all those spaces that we are now introducing them to through posts, photographs, videos, virtual visits, live streaming. Museums will need to continue to be friendly and continue to communicate with the public even after the emergency has passed: indeed, they may need to reflect on the fact that good (and especially targeted) communication tends to consolidate existing audiences and acquire new ones. Serious campaigns to promote reading will be needed (and I am not just referring to those lowered from above and decided between the benches of Parliament: everyone, including the individual citizen, can invite people to read even outside the framework of a national initiative) to make sure that the myriad hashtags spurring people to pick up the so-called “good book” do not remain just an excuse to take a picture of a plaid placemat with coffee cup and bestseller ordinance. The meritorious production of Spotify playlists on an almost industrial scale that we are witnessing these days will hopefully translate into a more massive presence in clubs, halls, and theaters. This is, of course, an invitation to the public as well.

A thought, to close, goes instead to all those workers who are forced to stay at home without certainty about their future. To the many precarious workers who in these hours, as denounced by the Unione Sindacale di Base, do not know if their contracts will be renewed, or if they will even lose their jobs. We are happy and proud of the fact that the Ministry of Cultural Heritage is continuing to organize social marathons from museums and places of culture: these are useful and intelligent activities, and moreover, they are gaining extraordinary public acceptance and success. But they will have to be followed up outside the network. In the last few days there have been many requests to the government: workers’ movements, trade unions, sector associations, councillors for culture, from the smallest ones up to Confindustria Cultura, all have emphasized, with a unity of purpose that has probably never been experienced before (and let’s treasure this too), the urgencies that need to be addressed. Everyone agreed that it is necessary and imperative to support the workers in the sector, trying to ensure that no one loses his or her job. But there is another aspect to highlight: awareness of the importance of culture will necessarily have to lead to awareness of the importance of those who work for culture. The emergency, we reiterate, has reminded us that without culture there is no living. But many culture professionals live with little: and so, lest the work of these days fall on deaf ears and not be remembered in the future only as a momentary hangover that will have left us with no memories and a severe headache, it will be appropriate to ask ourselves how to improve the conditions of those who work in the sector, how to increase the employment base, how to reach the public more and better than we have done so far.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.