It is due to the King of Naples Alfonso V of Aragon, known as Alfonso the Magnanimous (Medina del Campo, 1396 - Naples, 1458), that in his dense program of support for the arts, letters and culture in general, he initiated a library that was among the richest of the Renaissance. The idea of establishing a library arose not only from the conviction that it was the duty of a sovereign to make available to his kingdom an instrument that would be capable of spreading culture, but also from a sincere passion for books that the Aragonese prince had cultivated since he was a boy when, since 1413, he had started a small collection of books in Barcelona, consisting at first of volumes on sacred subjects, later enriched with Greek and Latin classics. These were books that were already able to testify to Alfonso’s taste and refinement, since they were illuminated codices produced in Aragonese territory. Thus, after the conquest of the kingdom of Naples, having established his own seat in Castel Nuovo (i.e., the Maschio Angioino), Alfonso began to prepare for the creation of the library, set up in a room overlooking the sea as we learn from the chronicles of the time, and of which precious codices commissioned ex novo by the king would have been part. One of these is a Breviarium romanum known as the “Book of Hours of Alfonso,” currently housed at the National Library in Naples: it is the oldest and most valuable of Alfonso’s manuscripts still in the city after the diaspora of his library.

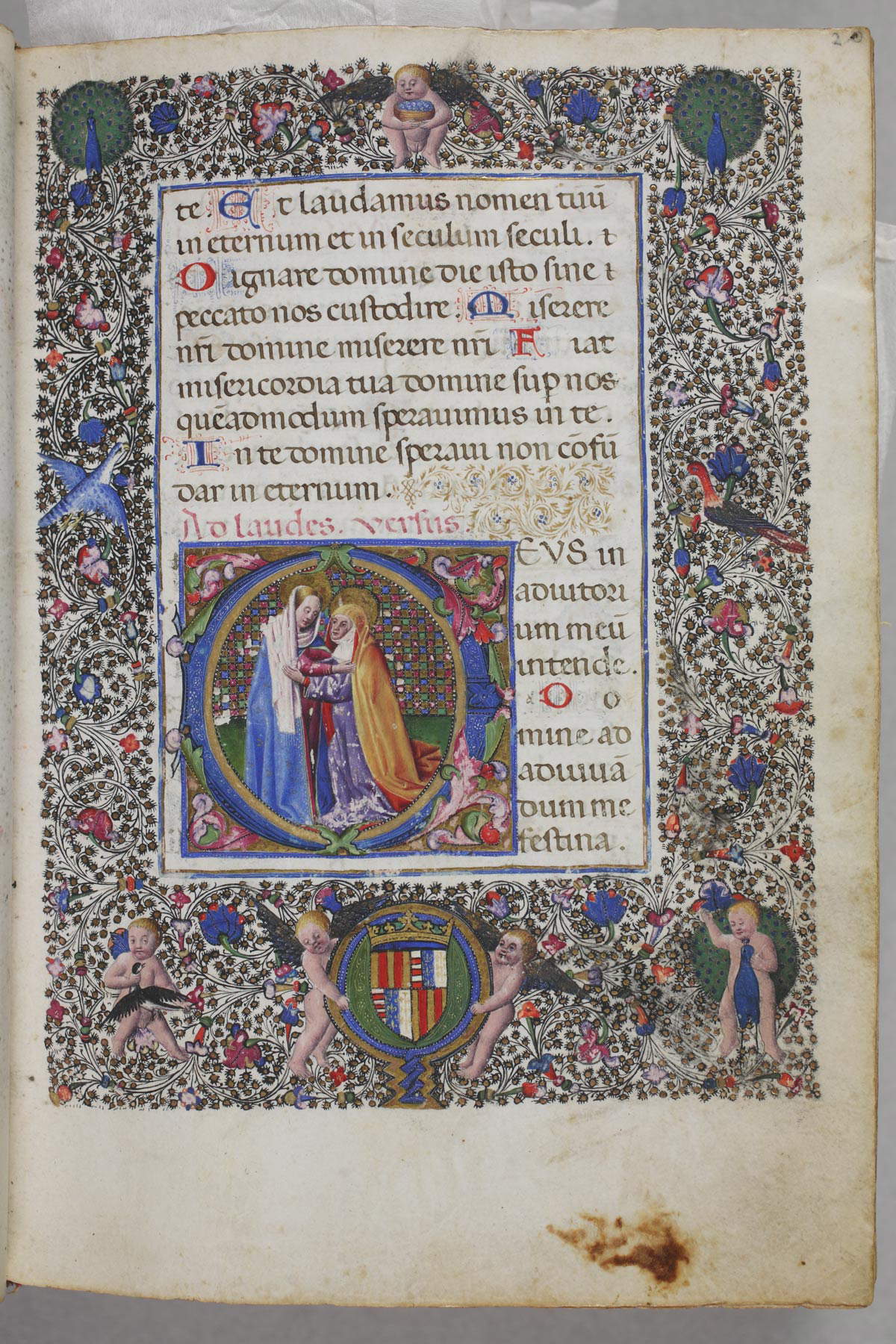

The Breviarium Romanum is a liturgical book containing the canonical hours (hence also the name “Book of Hours”) of the Catholic Church: it is, in essence, a volume, generally written in Latin, that punctuates the Christian’s day by listing the prayers (the “divine offices”) to be recited at the appointed hours. The Book of Hours of Alfonso the Magnanimous was compiled by the Ligurian humanist and copyist Jacopo Curlo, active in Naples between 1445 and 1459, was illustrated by three different illuminators who executed the thirty different sacred scenes that decorate the codex, and was probably made between 1455 (the date to which some payments for the supply of the scrolls date) and 1458.

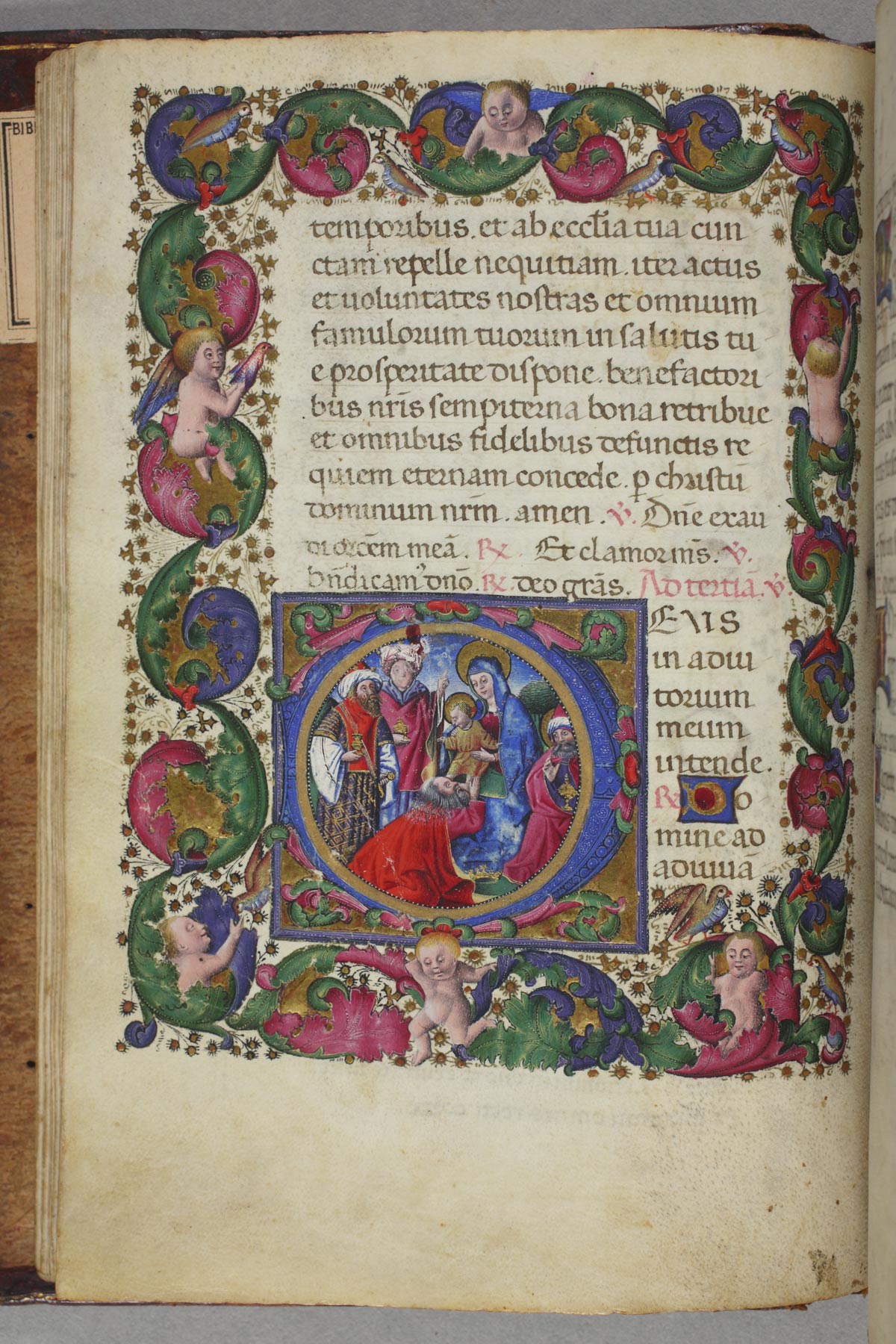

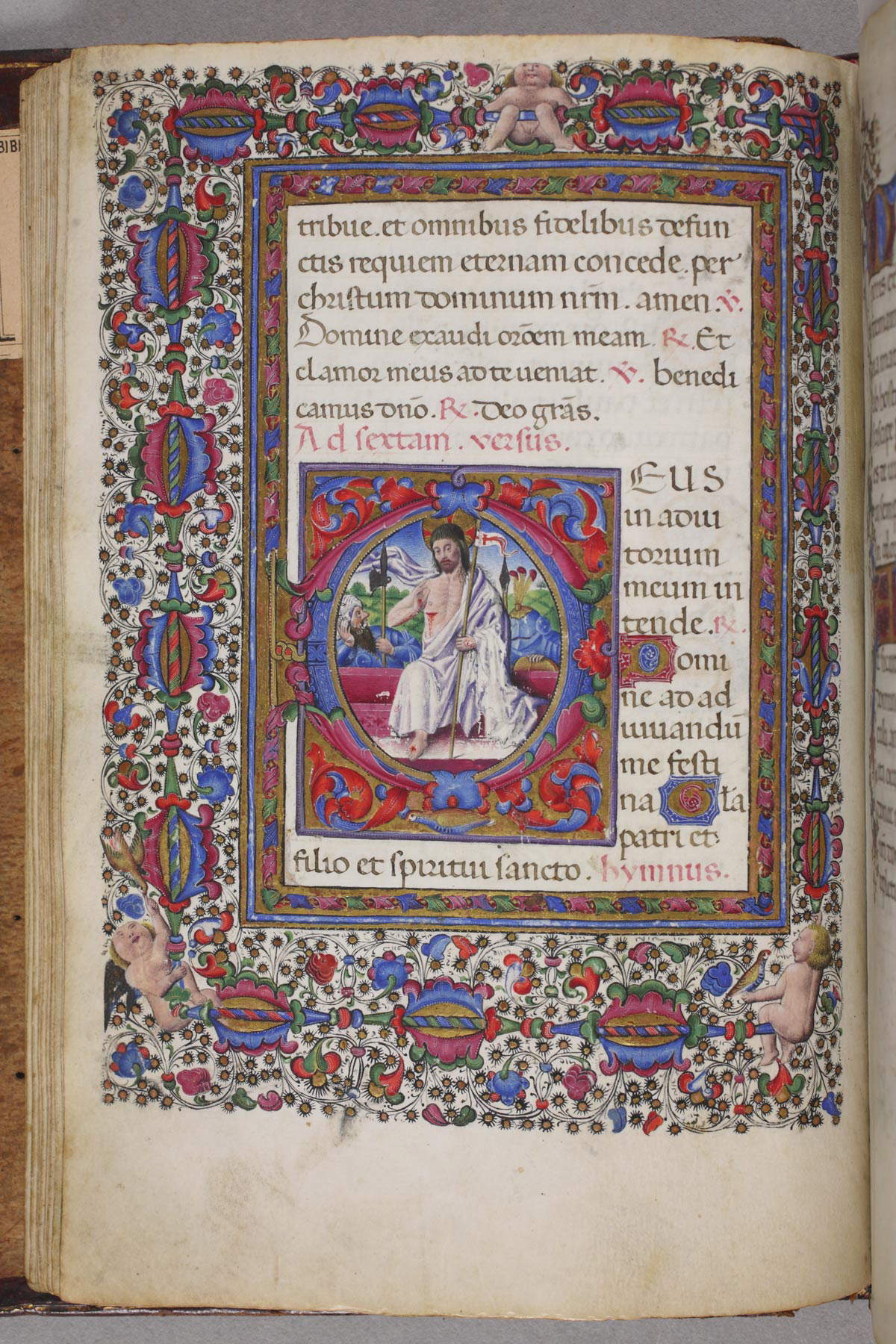

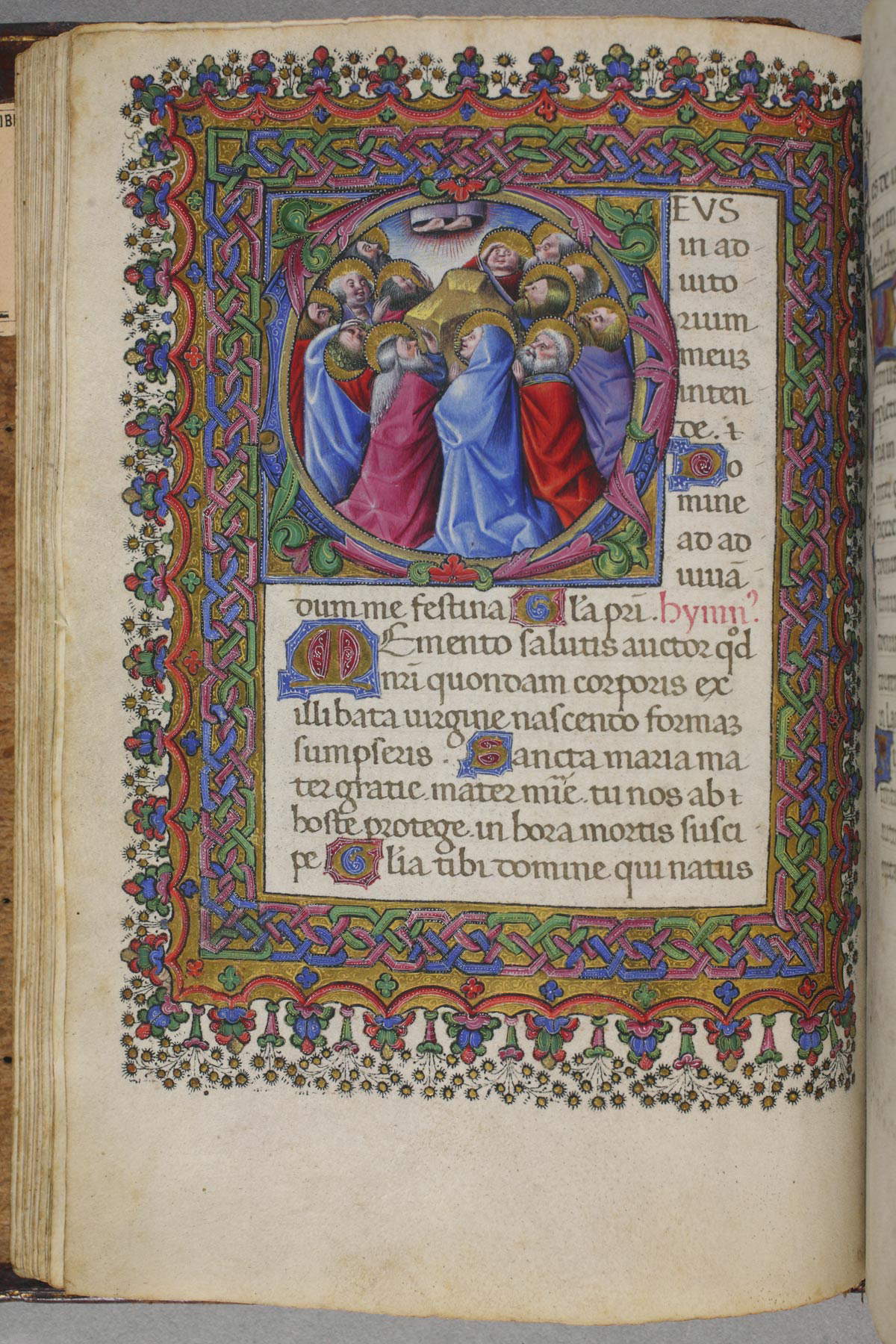

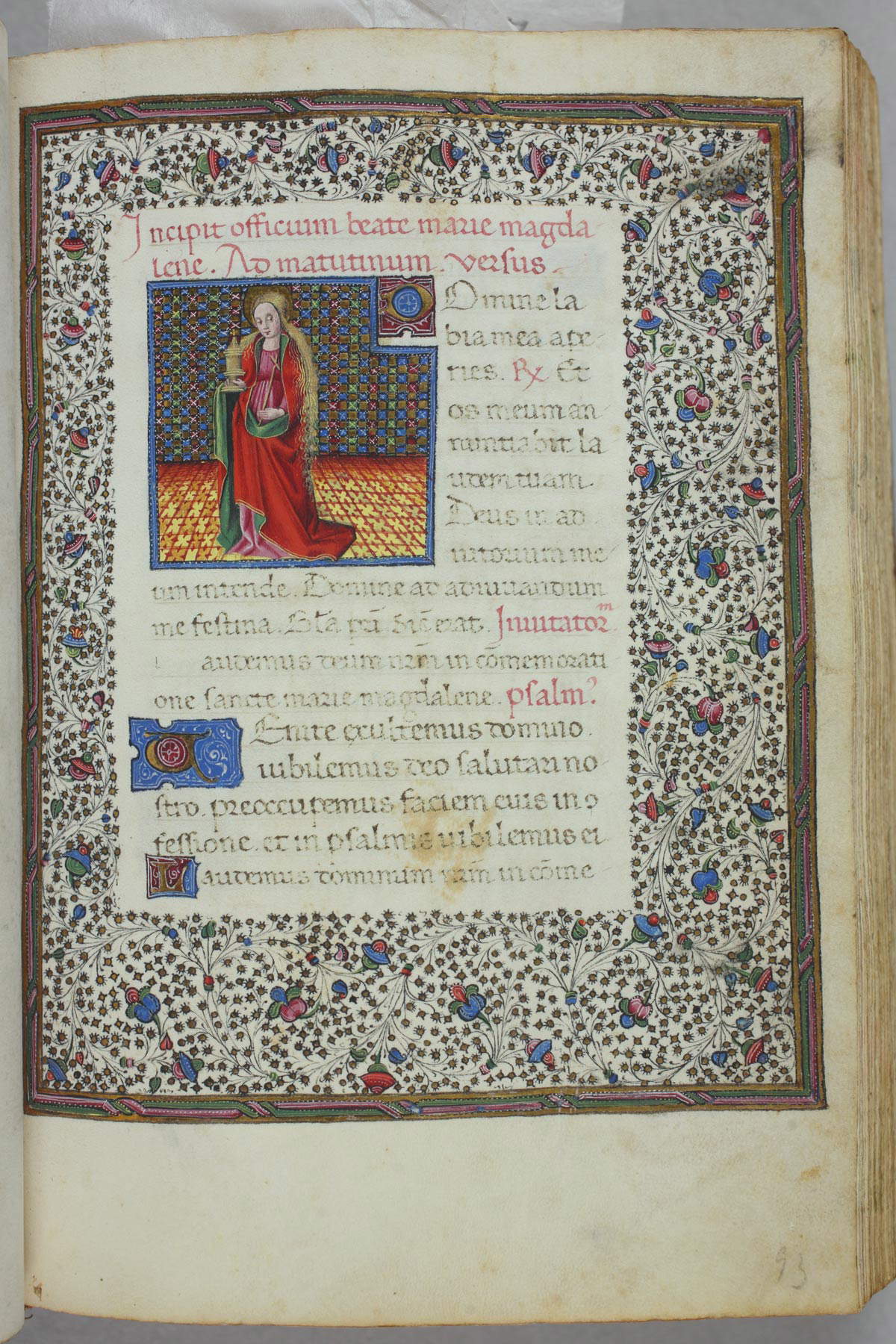

According to the scholar Antonella Putaturo Donati Murano, a specialist in miniatures, the first author executed the scenes of the Passion of Christ, and is shown to be an artist of Catalan origin ( azulejos floors typical of the Iberian peninsula appear in fact), with an eye, however, turned to the Franco-Burgundian miniature, on which the volumetric rendering of the figures depends. Then there is another author (initially thought to be two separate artists, later Putaturo Donati Murano considered that in fact those two seemingly different personalities could be traced back to a single artist), who is influenced by the Burgundian and Provençal culture that characterized the workshop of Colantonio, the principal Neapolitan artist of the first half of the 15th century, and a final artist, probably Flemish, who has been given the name “Master of St. George” by virtue of one of the miniatures attributed to him depicting the saint.

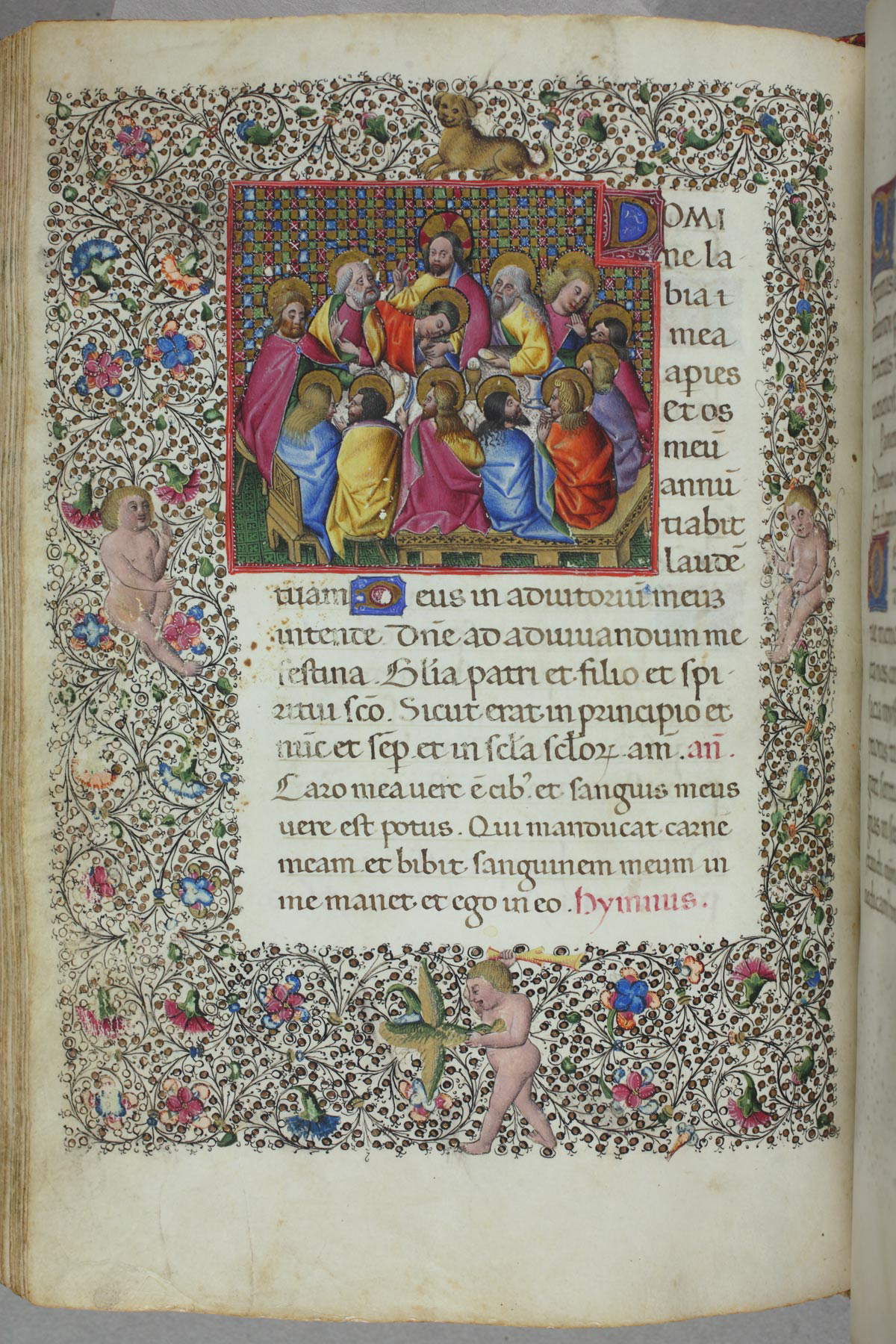

The first miniaturist, probably Spanish and of Valencian training according to Ferdinando Bologna’s hypothesis, is supposed to be the author of the scenes of the office of the Passion, namely the Capture of Christ, Christ before Caiaphas, Christ before Herod, Christ before Pilate, Pilate washing his hands, and the Crucifixion, and in addition theLast Supper has also been attributed to him because of the close similarities with the scenes of Christ before Caiaphas and Christ before Herod (same perspective layout, Christ with the same connotations). Because of the subjects of his scenes, this early illuminator of the Book of Hours of Alfonso the Magnanimous has been called the “Master of the Passion.” Also to the same master could be ascribed the fanciful and refined friezes on the cards, made in racemes populated with figures and animals, the latter characterized by a relevant degree of realism, which hints at a certain knowledge of Flemish art of the time, accustomed to very detailed renderings of subjects. Moreover, scholars have found tangencies with the art of the Valencian painter Jacomart Baço, so much so as to suggest that this unknown artist was a pupil of the Spaniard, who probably came to the city in the master’s retinue: Baço was in fact called to Naples in 1442 by Alfonso the Magnanimous himself (he was one of his favorite artists), and his presence had a considerable impact on the local school, orienting in particular the tastes of Colantonio and his workshop.

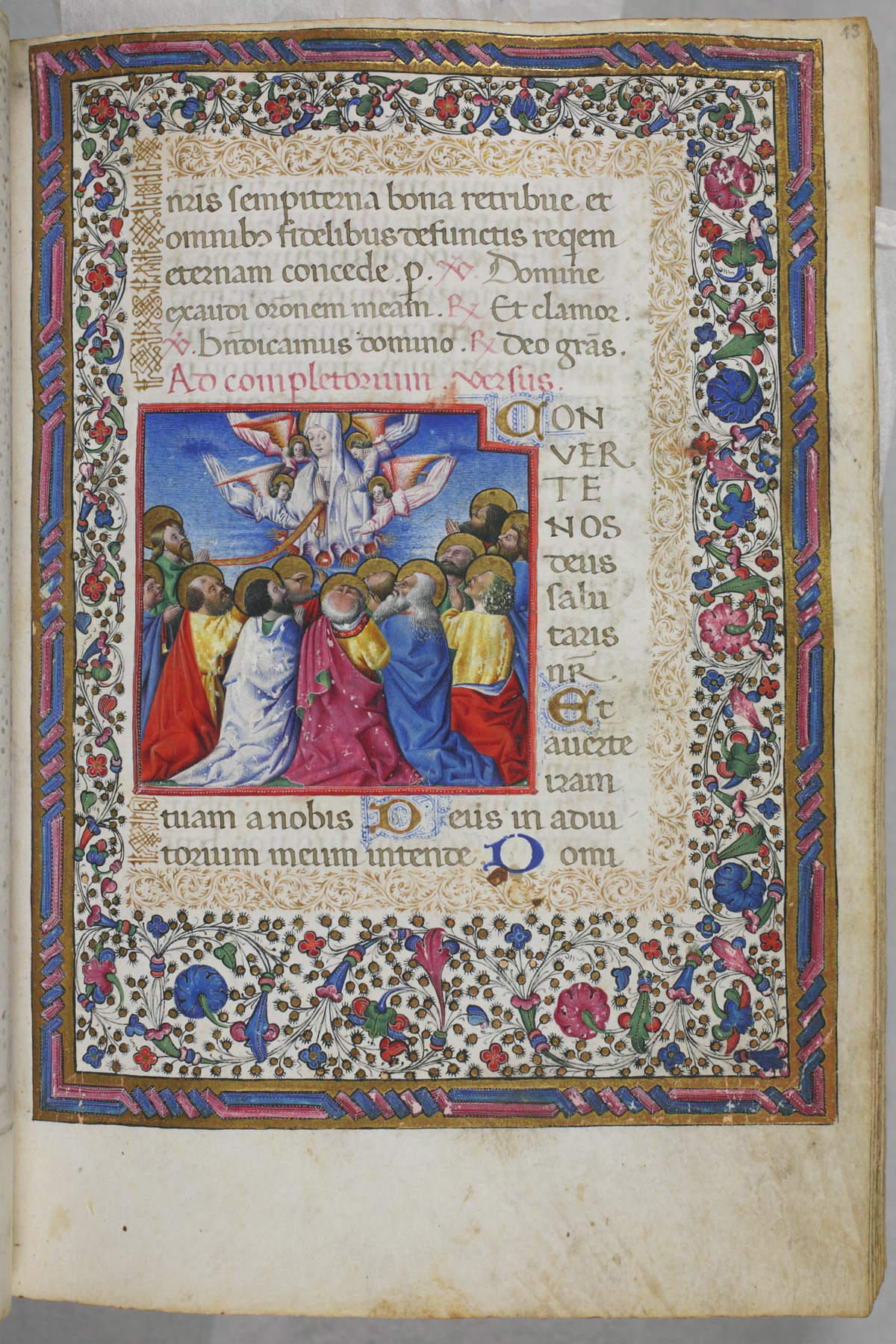

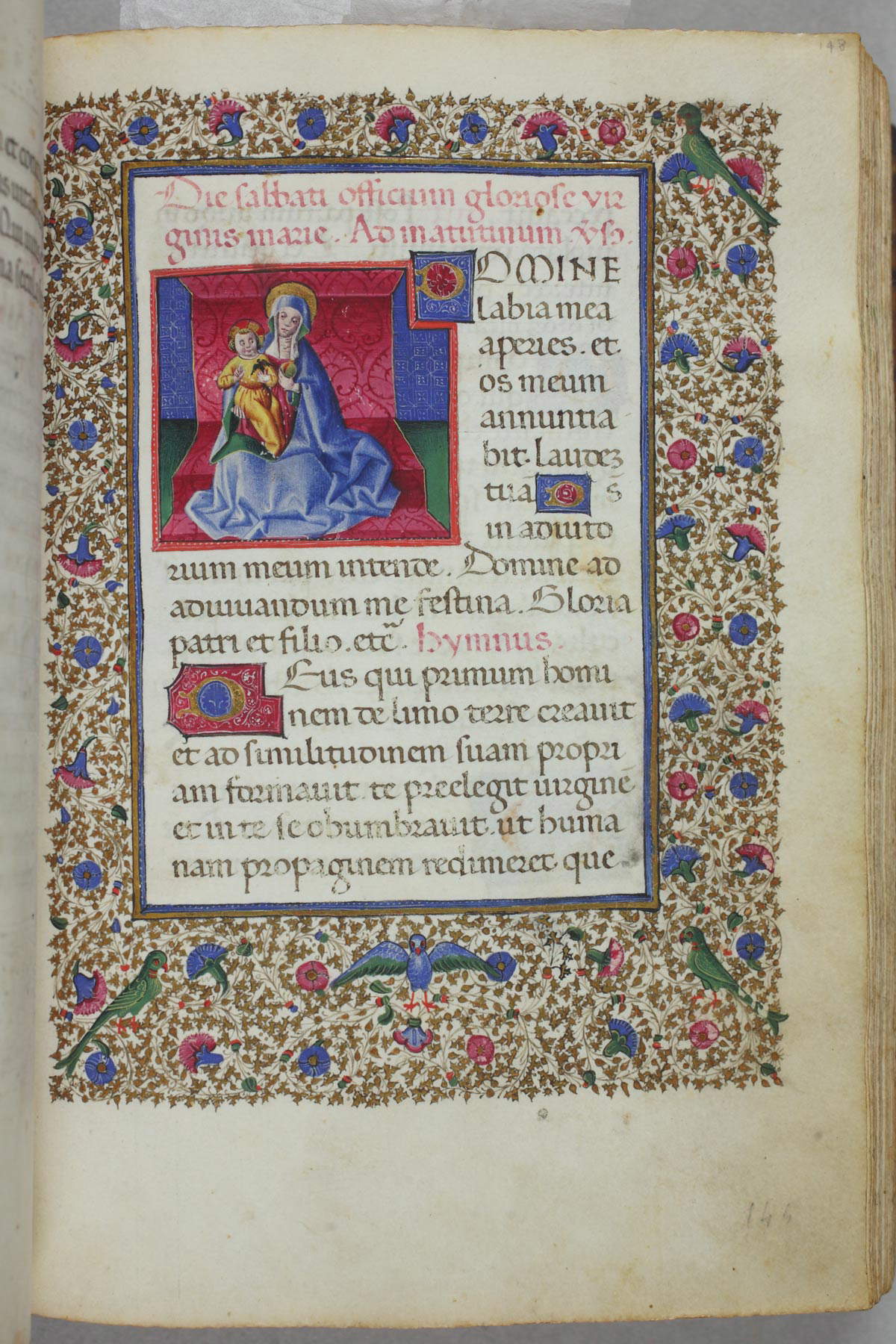

The second author is the one who produced the largest number of scenes: eighteen out of thirty are attributed to him, namely the Visitation, theAdoration of the Magi, the Resurrection of Christ, theAscension, theAssumption of the Virgin, the Prayer in the Garden, Pentecost, the Trinity, the St. Catherine of Alexandria, theFuneral Office, the Resurrection of the Saints, the Madonna and Child Enthroned, another Visitation, the Madonna and Child in the Vireto, the Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple, the Virgin of the Seven Gauds, the Symbols of the Passion, and the Deposition (the latter, moreover, is influenced by Roger van der Wayden’s altarpiece of the Deposition in the Miraflores retable that is now in the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin). This is an artist who probably trained in Colontanio’s workshop and who displays manners dependent on Flemish and Burgundian art (in particular, similarities have been detected with the art of Barthélémy van Eyck especially in the treatment of drapery), but also a certain closeness to Jacomart Baço, particularly in certain female figures. Singular then is the case of the third miniaturist, who produced the scene of Saint George and the princess, and who was probably asked by Alfonso the Magnanimous to reproduce a painting by Jan van Eyck having the same subject and which was among the sovereign’s favorite works. The same author probably also made the David at Prayer and the Nativity.

Book of Hours of Alfonso

Book of Hours of Alfonso

Although the Book of Hours of Alfonso the Magnanimous was born in Naples and is now in the Neapolitan city, it did not always remain on the shores of the gulf. In 1495, King Alfonso II, after abdicating in favor of his son Ferrandino, left Naples for Sicily and probably took his grandfather’s precious manuscript with him and then delivered it to the convent of Monteoliveto. Later, as we find from an ex libris affixed to the back of the book’s front plate, it ended up in the collection of the Prince of Torella, who had a rich book collection that was dismembered in 1896 after a sale in Paris. It was the Sterling family that purchased the Book of Hours, and the book left for England: it then passed to London collector Heinrich Eisemann, a lover of antique books. For some time, nothing more was heard of the codex, so much so that in the 1950s it was thought to have been lost: it then re-emerged in 1955 on the London antiquarian market, where it was purchased by the National Library of Naples, which was therefore able to return the book to where it had been made.

It is, in fact, one of the most precious products of the Naples of Alfonso the Magnanimous, as well as one of the main boasts of his rich library, that collection that in 1495 Marin Sanudo called “la libraria dil Re” where “it was assà copa di libri, in carta bona, scritti a penna, et coverti di seda et d’oro, con li zoli d’argento indorati, benissimo aminiati, et in ogni facultà,” and which was frequented by the most illustrious humanists of the time, such as Lorenzo Valla, Bartolomeo Facio, Giovanni Pontano, and Francesco Filelfo. It was the Naples of the “Renaissance turn,” as Liana Castelfranchi and Francesca Tasso have called it, the Naples at the center of the Mediterranean trade routes and which, thanks precisely to King Alfonso V, had established a solid link with Flanders, the Naples that attracted, perhaps more and better than any other city of the time, the best foreign artists: They stayed in the city at close quarters, in addition to the aforementioned Jacomart Baço, who was in Naples from 1442 to 1445, the Flemish Barthélémy van Eyck, who worked for Renato d’Anjou between 1439 and 1442, and the Frenchman Jean Fouquet, who was here perhaps around 1445.

Naples, at that time, had become, as art historian Edoardo Villata has written, “a nerve center of reworking Nordic figurative culture, mostly received through the mediation of Provence and Valencia, and of comparison with the Central Italian Renaissance tradition.” And the presence of Antonello da Messina, who arrived in Naples in 1450 and carried out his alumnuship with Colantonio, should also be mentioned: it was here that the young Sicilian most likely had the opportunity to make the acquaintance of Flemish art. Also because, as mentioned, Alfonso V was a great fan of Flemish art and his collection included paintings by Roger van der Weyden, Jan van Eyck, Petrus Christus and others. In Naples, in essence, the Renaissance departed declined in a form that perhaps it is not daring to call “cosmopolitan” and that was among the most original achievements of Italian art of the time. And the Book of Hours of Alfonso the Magnanimous is one of the highest witnesses of that happy season of the arts in Naples.

Book of Hours of

Book of Hours of

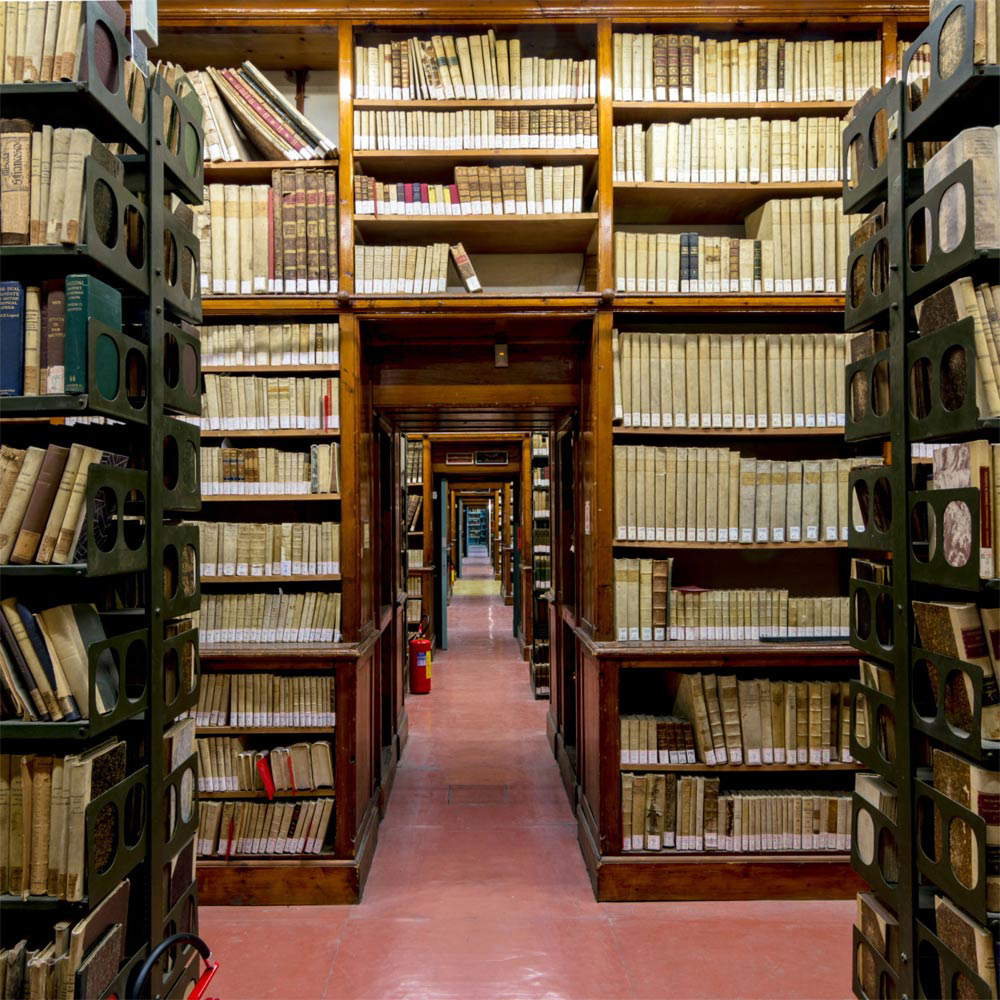

The National Library of Naples is the third largest state library in Italy, after the National Central Libraries of Rome and Florence, and its origins date back to the late 18th century, when at the behest of Ferdinand IV of Bourbon the book collections until then kept first in the Royal Palace and later in the Palace of Capodimonte began to be placed in the Palazzo degli Studi (now home to the Archaeological Museum). The transfer of volumes had begun in 1784, but it was not until January 13, 1804 that the Royal Library could be opened to the public. The holdings consisted of the core collection of the Farnese family to which convent and private funds had been added. During the French occupation, the library was further enriched with the funds of suppressed monasteries and new acquisitions, such as the Bodoni collection of Marquis Rosaspina and the incunabula of Melchiorre Delfico. From 1816 the Royal Library took the name of Bourbonica, and would assume the title of “National” after the Unification of Italy. Between the 19th and 20th centuries, the Library acquired the musical and theatrical collection donated by Count Edoardo Lucchesi Palli, the exceptional corpus of Giacomo Leopardi’s autographs through the testamentary legacy of Antonio Ranieri, a Neapolitan friend of the poet from Recanati, and the Herculaneum Papyrus Workshop, established by Charles of Bourbon for the purpose of preserving and carrying out the papyri from the 1752-1754 excavations at Herculaneum.

In the meantime, the headquarters of the Palazzo degli Studi had become inadequate to the size and needs of the institute, so in the 1920s, thanks to the determination of Benedetto Croce, it was moved to the eastern wing of the Royal Palace, for the occasion donated by Victor Emmanuel III to State Property. In that location those of the city’s historical libraries were attached to the collections of the Nazionale: the Brancacciana, the Provinciale, the San Giacomo, and the Library of the Museum of San Martino. In the same years, as a result of a clause in the Treaty of Saínt-Germain and the Vienna Art Convention, a group of invaluable manuscripts removed, at the behest of Charles VI, from the city’s rich convent libraries and transferred in 1718 to Vienna returned to Naples. The Library was closed in 1942 to save it from the risks of World War II (the director Guerriera Guerrieri had had the holdings transferred to some inland villages to secure them), and was able to reopen to the public in 1945. The latest chapter came in the 1990s, when the Library, in order to meet renewed space needs, expanded its premises to the premises in front of Piazza del Plebiscito, which were once home to the presidency of the Campania Regional Council. Today the National Library of Naples is managed by the Ministry of Culture.

The institution’s holdings include 1,799,934 printed volumes, 8,926 periodical titles, 798 microfiches and 2703 CD-ROMs, 19,758 manuscripts in volume and 153,606 loose documents belonging to private papers and archives, 500 parchments, 4.563 incunabula and about 50,000 cinquecentine, 6,940 prints and drawings, more than 6,000 historical maps and 21,600 photographs in historical photographic funds, 1,838 papyri and 4,665 papyrus drawings. Among the most valuable objects are those of the famous Farnese collection, which was started by Alessandro Farnese, later Pope Paul III, and increased by his grandsons and heirs, and was then had transferred to Naples by Charles of Bourbon in 1734 (among its volumes are valuable printed editions and manuscripts that are valuable only for their decorative apparatus, but also of great philological interest: for example, mention is made of Festus and Virgil). Also of great interest are the codex in the hand of St. Thomas Aquinas, which belonged to the Neapolitan convent of San Domenico Maggiore and whose fragments were donated to the people as relics, Pirro Ligorio’s Antiquities, Ariosto’s verses, Tasso’s Gerusalemme conquestata, the writings of Giovan Battista Vico and Giacomo Leopardi, and the testimonies of Teodoro Monticelli, Domenico Cotugno, Franesco De Sanctis, Benedetto Croce, and Giuseppe Ungaretti. And again, of great importance are the Leopardi autographs fund, which almost exhaustively collects the corpus of Giacomo Leopardi’s autographs (in addition to the autograph documentation of most of the Canti and Operette morali, the fund preserves the author’s manuscripts of works such as the Saggio sopra gli errori popolari degli antichi (1815), and the 4526 pages of the Zibaldone (1817-1832), Finally, it is preserved at the National Library of Naples is the Herculaneum Papyri Fund, which collects the papyri (unrolled and unrolled) unearthed at Herculaneum, between 1752 and 1754, during the excavation of the villa known as the “Villa of the Papyri” or the “Villa of the Pisoni.”

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.