At the end of the 19th century,Italy, then a young nation that had just been unified, was still a land of deep regional differences, disconnected cities and countryside, and strongly rooted local cultures. However, major economic and infrastructural transformations, the significant expansion of the railway network, the development of commerce and the urban bourgeoisie paved the way for a new idea of a country, that of a land that could be traveled, told, visited. It was, essentially, the birth of tourism. In this climate of profound change, tourist posters took shape not only as promotional tools, but almost as the basis for a new national visual identity. Tourist posters were, even before mass photography, newsreels or television, the first to fix in the minds of travelers - Italians and foreigners - the iconic image of the so-called “Bel Paese.”

The reconnaissance carried out on the occasion of the exhibition Visitate l’Italia! Tourism Promotion and Advertising 1900-1950 (Feb. 13 to Aug. 25, 2025, in Turin, Palazzo Madama, curated by Dario Cimorelli and Giovanni C.F. Villa), significantly retraced the stages of this history, a history that allows us to read, precisely through advertising graphics, also the social, cultural and economic history of our country.

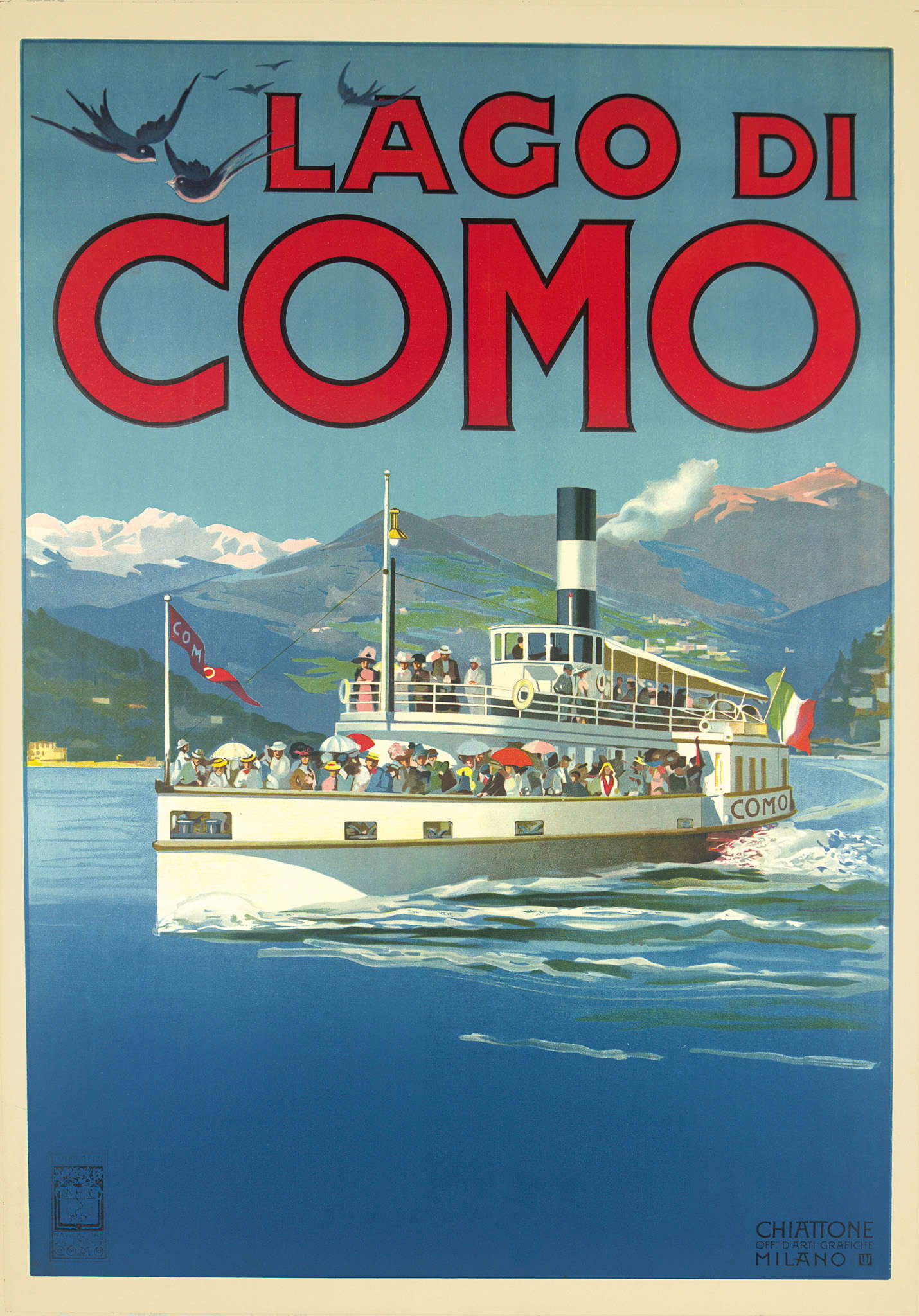

If the 18th-century Grand Tour had destined Italy for young European aristocrats as a stage of cultural education, the new tourism of the late 19th century appealed to a middle class eager to experience travel no longer as a study of antiquities, but as an experience of pleasure, well-being, and aesthetic discovery. The classic stops of the Grand Tour, such as Rome, Florence, Naples and Venice, remained unavoidable, but new destinations were now being added: Lombard lakes, Ligurian beaches, Alpine spas, minor art towns, the Romagna Riviera. To promote these places and tickle the imagination of an ever-widening public, a new, quick, immediate language capable of evoking emotions at first glance was needed: the illustrated poster.

The art of the poster in Italy developed in parallel with the evolution of lithographic technique. If, in France, Jules Chéret had given birth to colorful and popular graphics, in Italy the age-old figurative tradition and sensitivity to the landscape decisively influenced the birth of tourist poster art. Early Italian posters did not simply promote travel or hotels: these works sought to construct an entire imagery, to synthesize in a single image the promise of beauty, serenity, and culture that Italy offered. It is curious to trace the birth of the first Italian tourist poster, because it was not the advertisement of a particularly world-famous destination: the first city, Dario Cimorelli recalls, to “try its hand” at using these promotional tools was Fano, which in 1893 commissioned the G. Wenk and Sons lithography of Bologna to produce its billboard in a run of two thousand copies. “The technology is new and the investment substantial,” Cimorelli writes, “but the creative and technical resourcefulness allows the project to materialize. This first poster is designed to be used for several seasons, so as to divide the cost of production over several exercises: thus the surface is divided into parts, one of which is printed in color and another, smaller one, is left free - at the bottom, or on the side - to be printed from time to time with the new information of the season.” Trying their hand at making these posters are, especially in the beginning, painters, after which important figures of artists will emerge who will devote a significant part of their efforts precisely to poster design.

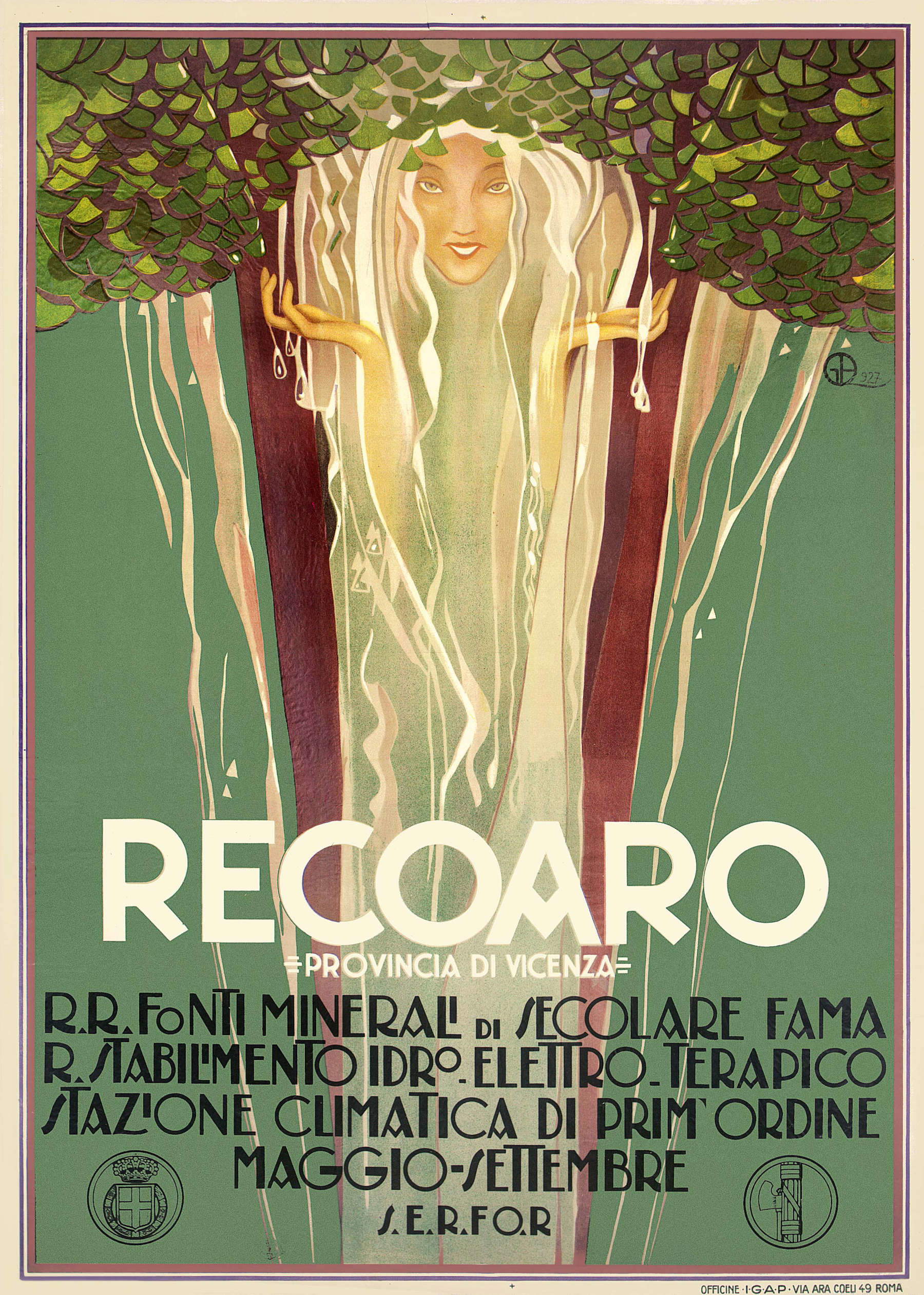

The Touring Club Italiano, founded in 1894, played a fundamental role in spreading a new conception of travel as an education of body and spirit. The State Railways, established in 1905, systematically promoted tourist destinations along the new railway lines. The posters created for these institutions were not mere commercial tools, but powerful representations of the Italian landscape and history. Giovanni C.F. Villa, echoing an insight of Gerardo Dottori who, in 1931, had this new art form as “the most suitable to directly influence the aesthetic taste of a people”, observes that the first tourist posters merely popularized “forms and styles that from eclecticism to floral - Art Nouveau, Art Nouveau, Jugendstil - onward, through the various avant-gardes, would surpass the first visual declinations of the late 19th century.” Posters thus become “the immediate expression of Italian creativity in tourism promotion, also proposing the primacy of an idea of landscape, an element that will have an irrepressible fortune” thanks also to the variety of Italian environments.

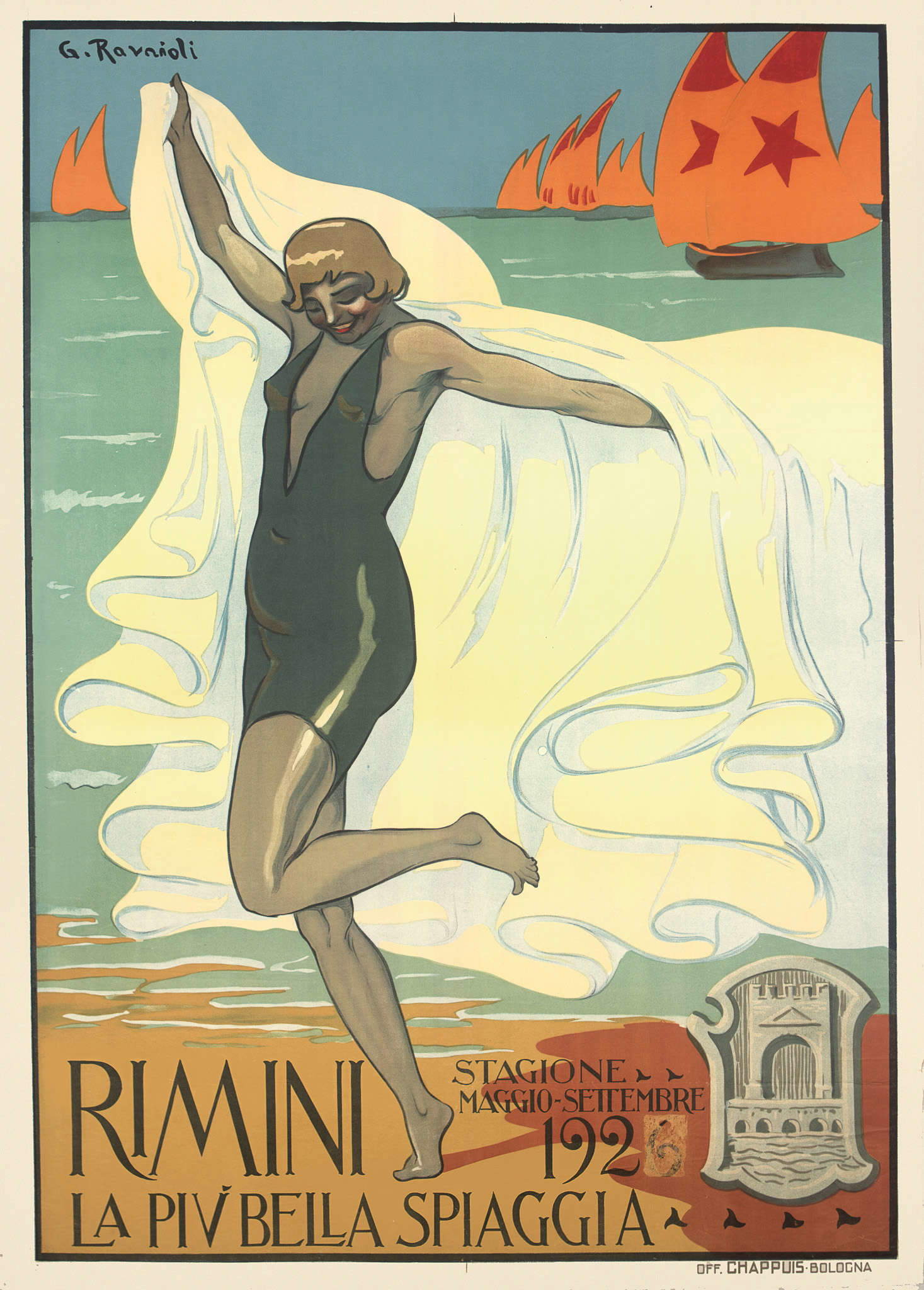

Among the pioneers of this season were names such as Leopoldo Metlicovitz (Trieste, 1868 - Ponte Lambro, 1944), a Mitteleuropean-trained artist from Trieste who was able to blend descriptive precision with the grace of Art Nouveau decorativism. In his posters dedicated to Lombard lakes or international exhibitions, nature is transformed into an orderly, harmonious, poetic space. Another absolute protagonist was Marcello Dudovich (Trieste, 1878 - Milan, 1962), also from Trieste, who was able to interpret the transition from the Art Nouveau style to a new graphic modernity made of wide color fields, soft lines, light and dreamy atmospheres. His posters for Rimini, Venice or Padua tell of a summery, vital, young, fascinating Italy.

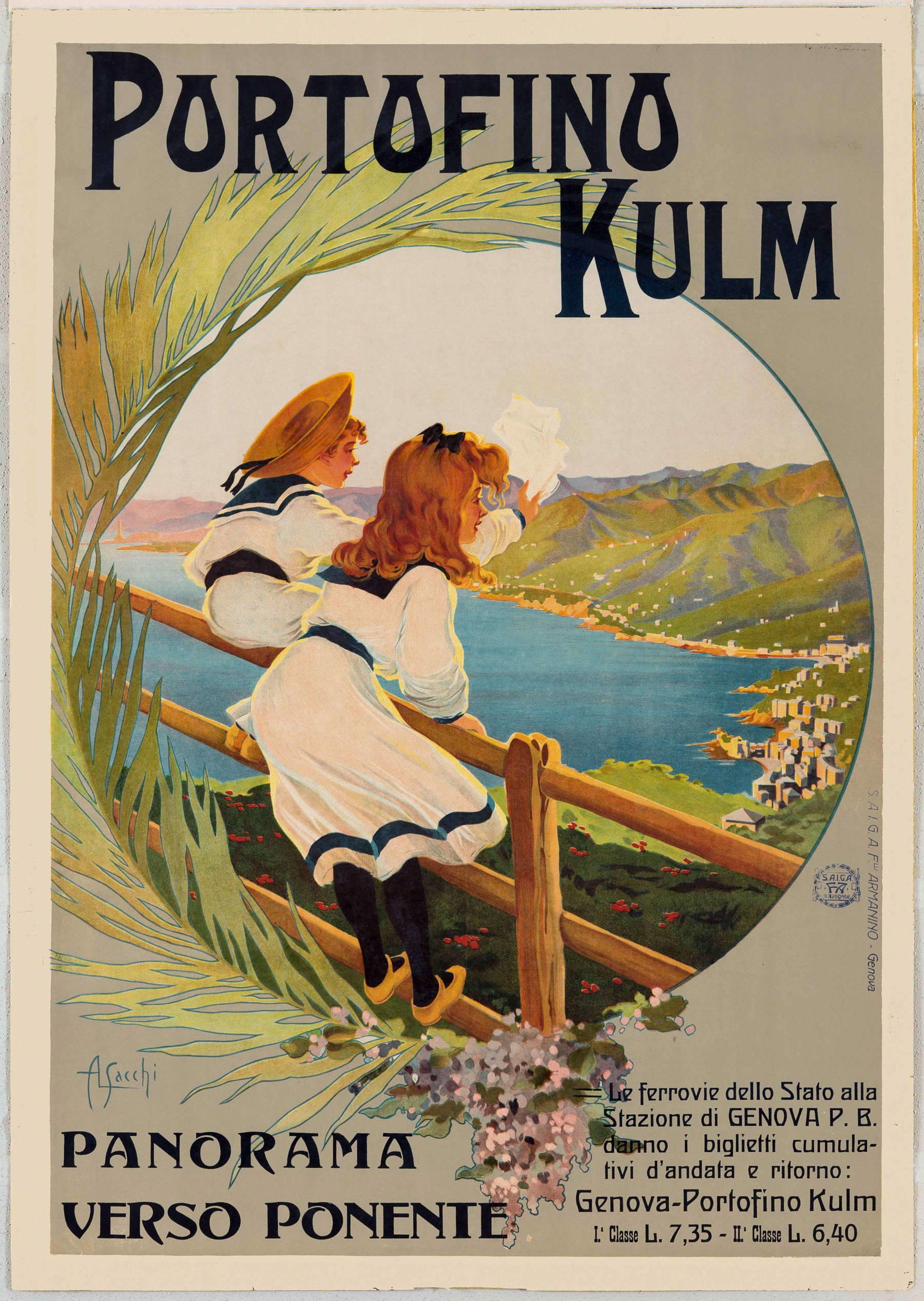

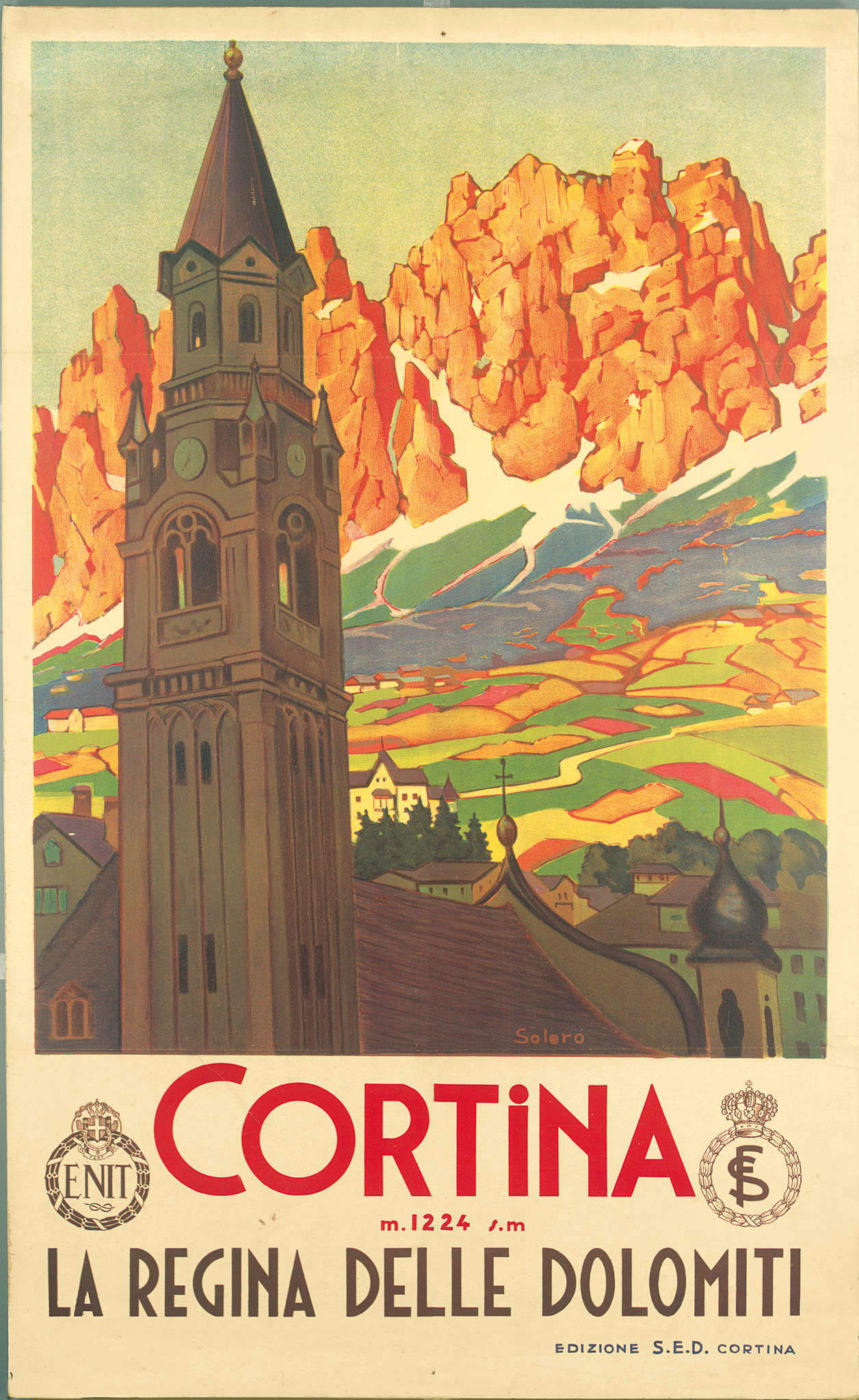

Perhaps even before them, however, it was Adolf Hohenstein (St. Petersburg, 1854 - Bonn, 1928), a German artist transplanted to Italy, who launched a new season by bringing the refinement of Viennese and Central European currents into the Italian poster. His contribution was in fact fundamental in defining an elegant and stylized graphic style capable of evoking the luxury of the spa resort or the suggestion of cities of art. Villa also identifies, among the masterpieces of this new art form, a view of Portofino by Leonetto Cappiello (Livorno, 1875 - Cannes, 1942), an artist active mainly in Paris who was able to innovate the visual language of the poster by introducing bold, symbolic images far removed from naturalism. The poster contains all the elements that appealed to the imagination of tourists in those years: views, beautiful Italian ladies, elegance in dress, and the colors of the Italian landscape. The famous poster of 1905, created for the Portofino Kulm Hotel, with the colorful figures silhouetted against the vibrant background of the Ligurian landscape, then also marks a turning point in the tourist imagination: travel is no longer just contemplation, but emotional participation. Natural then to note that the posters appealed to certain commonplaces: for example, writes Villa, the mountains as majesty “to be contemplated in jacket and socks” (and then, from the 1920s, would also become a destination for winter sports), the sea as a place of entertainment, and the cities identified with their main monuments, with the posters suggesting to tourists, through the use of the imperative, the attractions not to be missed. Thus begins, Villa notes, also the search for the elements of a canon made up of icons, viewpoints, glimpses of views that will eventually identify a tourist destination by marking its image to the present day.

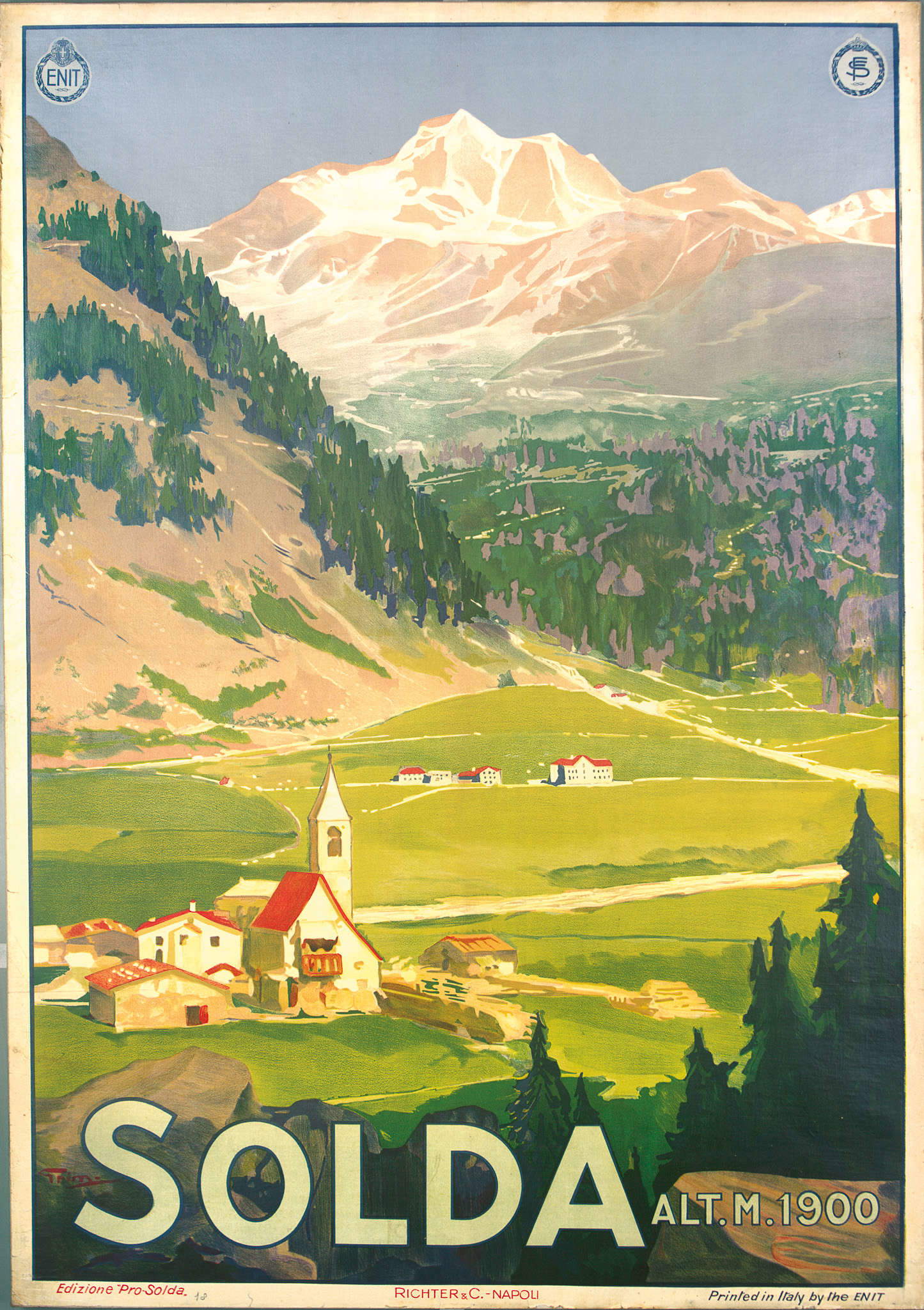

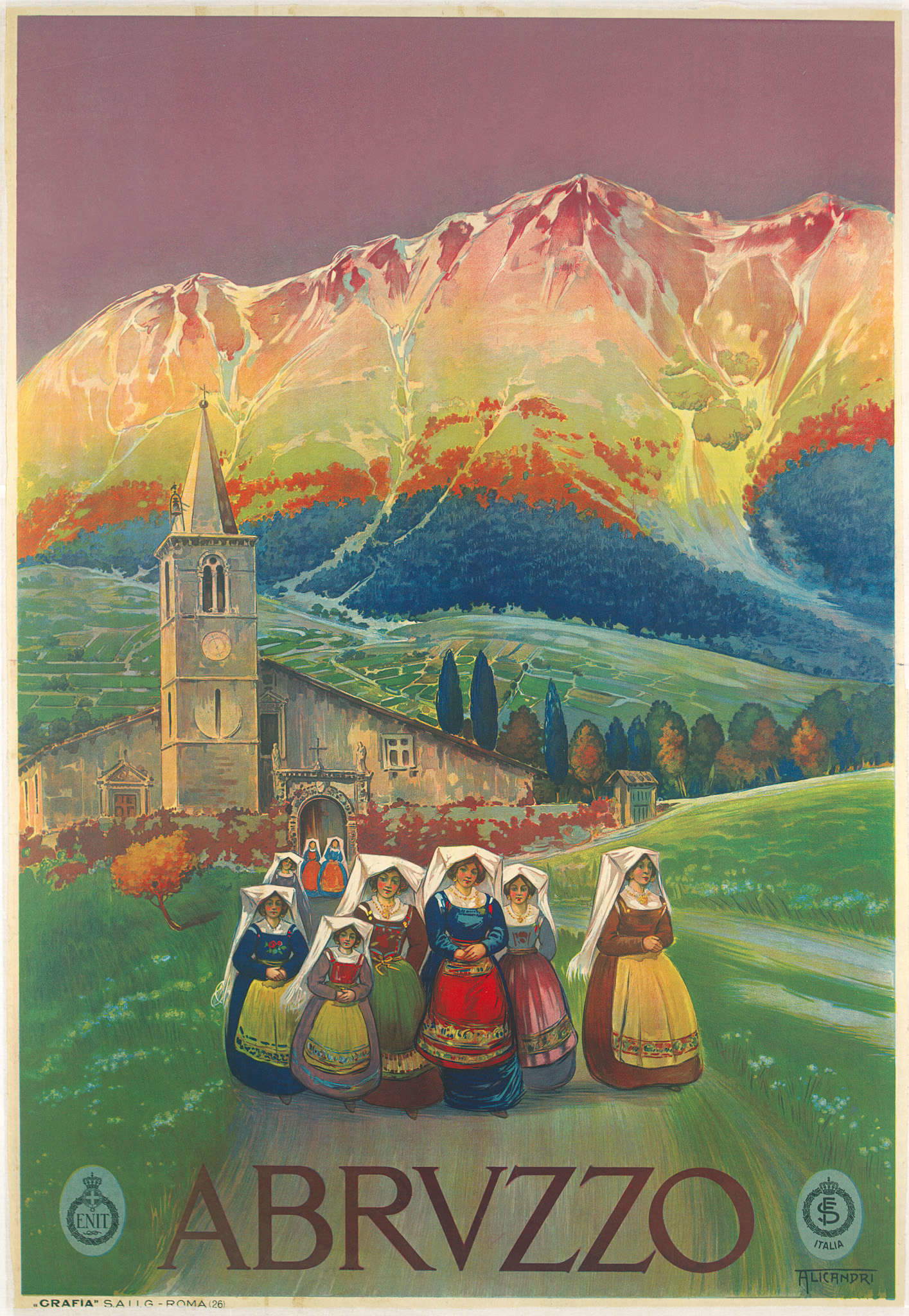

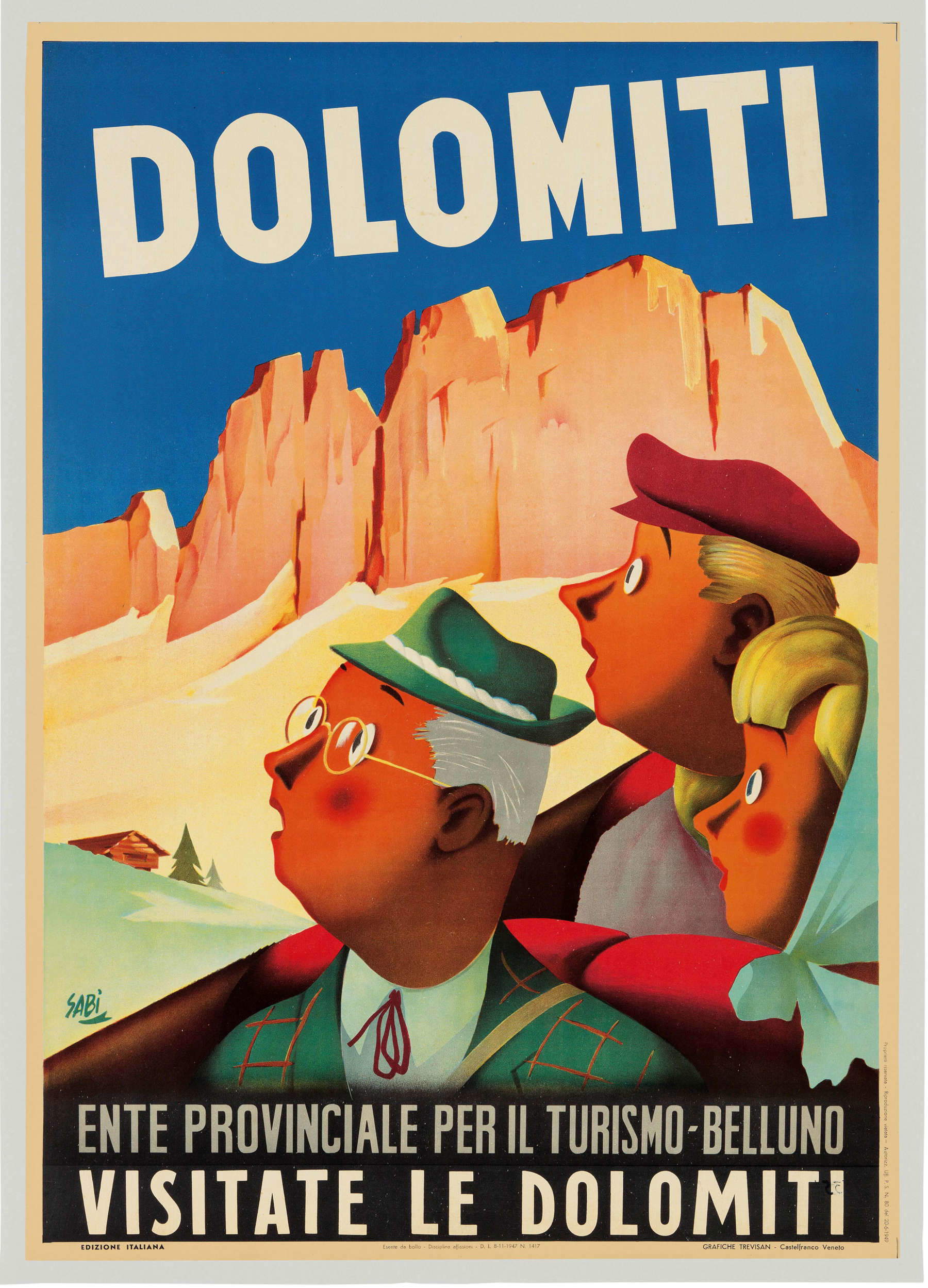

It was precisely the landscape, in the early poster works, that took on a central role: from the Dolomites to the Tuscan hills, from pre-Alpine lakes to Mediterranean gulfs, every glimpse was transformed into an instantly recognizable icon. These were not simply realistic reproductions: the posters operated a poetic stylization, accentuating colors, lights, and geometries to make the landscape even more seductive, even more archetypal.

With the creation of theEnte Nazionale per l’Incremento delle Industrie Turistiche (ENIT) in 1919, tourism was definitively recognized as a strategic sector for Italy’s economy and international image. ENIT produced an impressive amount of promotional material: posters, brochures, postcards, guidebooks. Tourism graphics became a true identity-building tool. Through targeted iconographic selections, stereotypes destined to last for decades were consolidated: Venice as the city of love and dreams, Rome as the cradle of civilization, Florence as the heart of the Renaissance, Naples as a natural paradise.

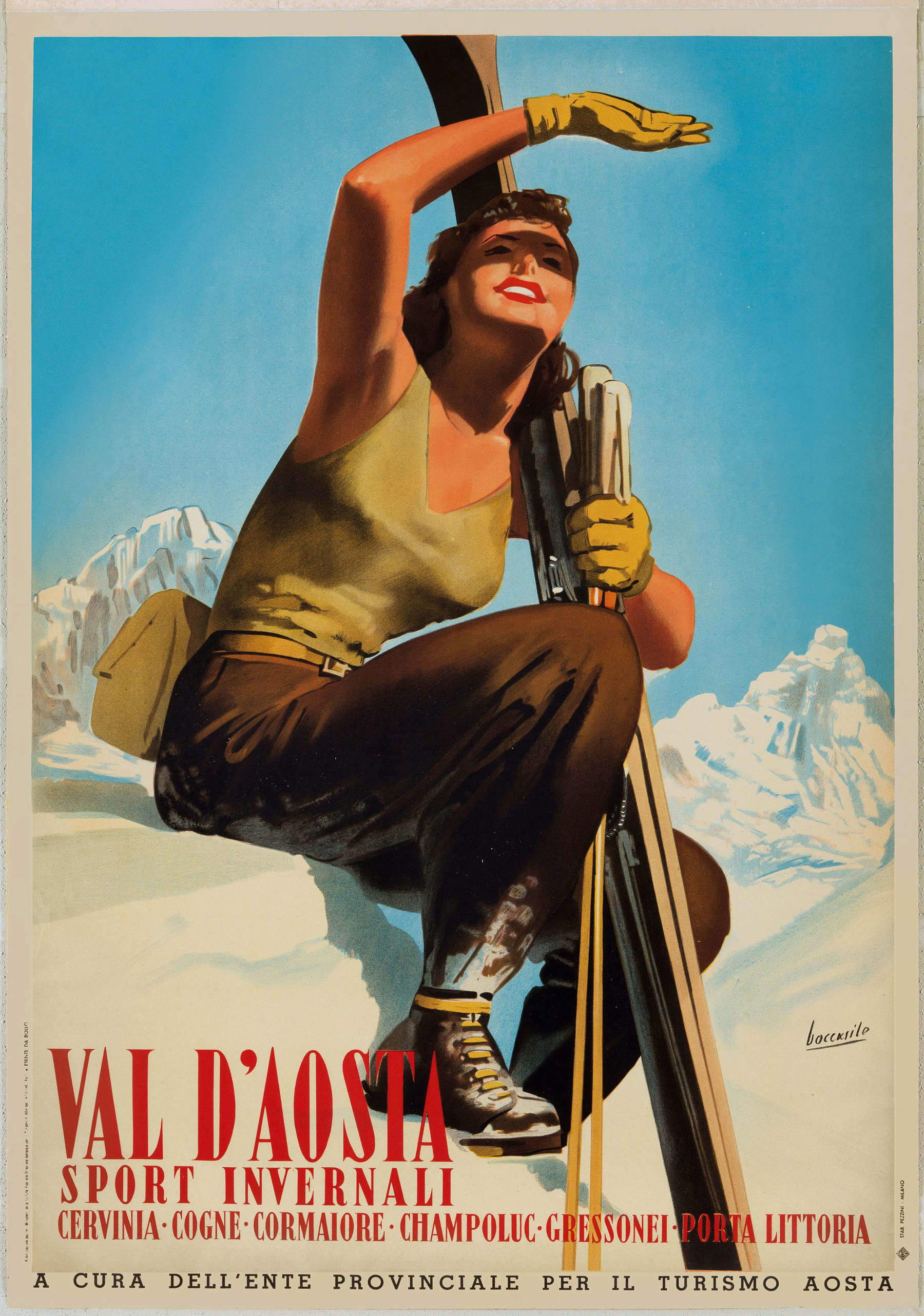

The transition from the 1920s to the 1930s brought further changes. The Art Nouveau language gave way to a more sober modernism, influenced by the European avant-garde and the needs of political propaganda. During the fascist regime, tourism was championed as a means of legitimizing national prestige. Tourism graphics celebrated not only the glorious past of classical and Renaissance Italy, but also the modernity of new infrastructure, seaside colonies, and ski resorts such as Sestriere, built from scratch in the 1930s. Posters such as the one by Gino Boccasile, with the famous “girl in green” in the snow, summarized in a single glance the freedom, health, youthful beauty and architectural modernity of the new Italy. The mountain posters of the 1920s and 1930s radically changed the imagery of the mountains: from a remote and picturesque place it became the scene of sports, vitality, and progress. Images of skiers, hikers, and young athletic climbers replaced romantic views of lonely valleys. The depiction of women also changed: slender, athletic, modern, the female figures on tourist posters embodied a new ideal of emancipated femininity, far from both the traditional Mediterranean figure and the rhetoric of the mother and bride. In the 1930s, the figure of Virgilio Retrosi (Rome, 1892 - 1975), a pupil of Duilio Cambellotti, stands out in particular, the author of posters that, Villa writes, “are striking for the presence of an important sign in the foreground: the Roman column, or the beach umbrella, or the overhang of a lintel, dominant elements immediately endowed with communicative poignancy, as well as immediate visual impact,” and which respond to a visual policy that “tended increasingly to impose an immediate canon and language.”

A strong stylistic change can be seen in posters in these years, compared to those of the late 19th or early 20th century, well summarized by Anna Villari: “If the language that advertising adopts in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, in the wake of mainly French examples of a few years earlier, is that of evocation, setting, and mimesis, with results strongly influenced by the sinuous finesse of the Art Nouveau style and with the human figure, idealized and rarefied, as the sole protagonist of scenes ’set’ in elegant interiors or exclusive exteriors, starting especially from the 1920s here appeared - as even contemporary critics recognized with some amazement - in Italian graphic art, the subject of studies and in-depth studies in specialized magazines and in the vanguard even compared to that of other European countries, echoes of the main artistic movements of the time: Cubism, Metaphysics, German-based Rationalisms. In a gradual abandonment of the delicate fin de siècle refinements, the human figure, while remaining the main character, takes on a new character: solidly constructed, traced with sharp markings and decisive, well-defined colors, it becomes more real, dynamic, brilliant.” The posters of the 1920s, it could be said, begin to dry up: they no longer have the elaborate character of those of the previous decades, but become more immediate, homogeneous, they set themselves the goal of immediately capturing the viewer’s attention and fixing themselves in his memory.

In the postwar period, after the tragedy of World War II, tourism in Italy slowly resumed. The new season, marked by the economic boom of the 1950s and 1960s, saw increasingly mass tourism. The tourism poster, while maintaining a central function, changed its face: themes became lighter, sunnier, more popular. Artists such as Ligurian artists Mario Puppo (Levanto, 1905 - 1977) and Filippo Romoli (Savona, 1901 - Genoa, 1969) painted a smiling, young, welcoming Italy, where travel was synonymous with freedom, joy, well-being. The posters showed sunny beaches, elegant girls, views dazzling with light. After all, the Italian “economic miracle” found in tourism one of its main engines. New highways, accessible utility cars like the Fiat 500, and the spread of paid leisure allowed millions of Italians to discover their country, while foreign tourists returned en masse to populate the cities of art, the coasts, and the lakes.

Finally, the posters of the 1950s and 1960s maintained the iconographic legacy of previous decades, but updated it to a more immediate and joyful taste. The tendency to fixate on certain icons remained - Brunelleschi’s dome for Florence, the smoking Vesuvius for Naples, the Colosseum for Rome - but lighter, everyday images also multiplied: couples laughing on the beach, families enjoying the sun, children playing in the waves. The tourism poster, in essence, adapted to the new demands of mass tourism, while retaining the ability to evoke dreams, desires and atmospheres, and helping to consolidate the myth of Italy as a privileged destination for international tourism. Even today, these posters represent not only a historical and artistic testimony, but also a living heritage, capable of speaking to a global audience and inspiring new generations of travelers.

The history of Italian tourism posters, from the end of the nineteenth century to the 1960s, is therefore also, wanting to summarize and also trying to broaden the view, the history of the construction of a myth. A myth that, while idealizing and simplifying often to the point of trivialization and cancellation of complexity (after all, the effects of tourism that focuses only on a few places are still felt today), was able to capture the deep heart of Italy: its infinite variety of landscapes, the millenary stratification of its culture, the sweetness of its light, the passion and joie de vivre of its people. And even today, looking at those posters, we cannot but recognize ourselves, cannot but feel, under the stylized elegance of those images, the pulse of a land that continues to enchant the world.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.