The year 2021 has been an important year for Turkey in the area of Cultural Heritage, especially for that region of Anatolia, also known as TaşTepeler (literally “stone hills”), which has been the subject of major excavation campaigns over the past two centuries, especially in the area of Şanlıurfa. A city formerly known as Edessa, Şanlıurfa was one of the most active stages of the so-called Neolithic Revolution, a transitional period during the Late Stone Age (10,000 B.C.-3.500 B.C.E.) in which humans went from being hunter-gatherers, associated in small nomadic groups, to organizing themselves into sedentary communities moved by an increasing collective feeling. It is therefore not surprising that it was in Şanlıurfa that the Taş Tepeler project was announced in September 2021: a plan of action that, in addition to protecting the archaeological sites that have already emerged, enshrines close cooperation between the Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism, the Şanlıurfa Archaeological Museum and a number of prestigious Turkish and international universities, with the goal of launching new excavation campaigns in Anatolia by 2024.

There are already 12 appreciable protohistoric sites in the TaşTepeler region. Foremost among them is the grandiose Göbekli Tepe, which its greatest scholar, Klaus Schmidt, at the time of the findings believed to be the oldest temple in human history; currently the world of archaeology is in agreement that the complex is “one of the earliest manifestations of man-made monumental architecture,” as stated in the UNESCO documentation on Göbekli Tepe, which has been a World Heritage Site since 2018. Then there is its “sister temple” Karahan Tepe, discovered in 2019 and almost contemporary with the first in chronology, scheduled to open to the public in 2022. Just a few months ago it was joined by the Sayburç site , a small excavation located in the perimeter of a rural dwelling in a neighboring farming district of Şanlıurfa. In addition to these finds, the TaşTepeler includes the sites of Yenimahalle-Şanlıurfa, Çakmaktepe, Hamzan Tepe, Sefer Tepe, TaŞlı Tepe, Kurt Tepe, Gürcütepe, Harbetsuvan Tepe, and Ayanlar Höyük.

Visiting these places today requires complex but not impossible organization. Şanlıurfa is a great place to start, a city very open to tourism and eager to showcase a region brimming with treasures. Don’t miss a visit to the city’s Archaeological Museum, one of the most important nationwide, with an extraordinary collection of 74,000 artifacts and artifacts from the Chalcolithic to the Hellenistic, Roman, Byzantine and Islamic periods. The museum itinerary, strong in elegant, functional design and of the highest quality, includes 14 main exhibition halls and various spaces used to house models of prehistoric buildings, nomadic settlements, mannequins of Neolithic men and women engaged in activities daily life, and even environmental reproductions of Anatolian sites, such as Göbekli Tepe and the village of Nevali Çori (the latter not reproduced but relocated in its original form to a room in the museum).

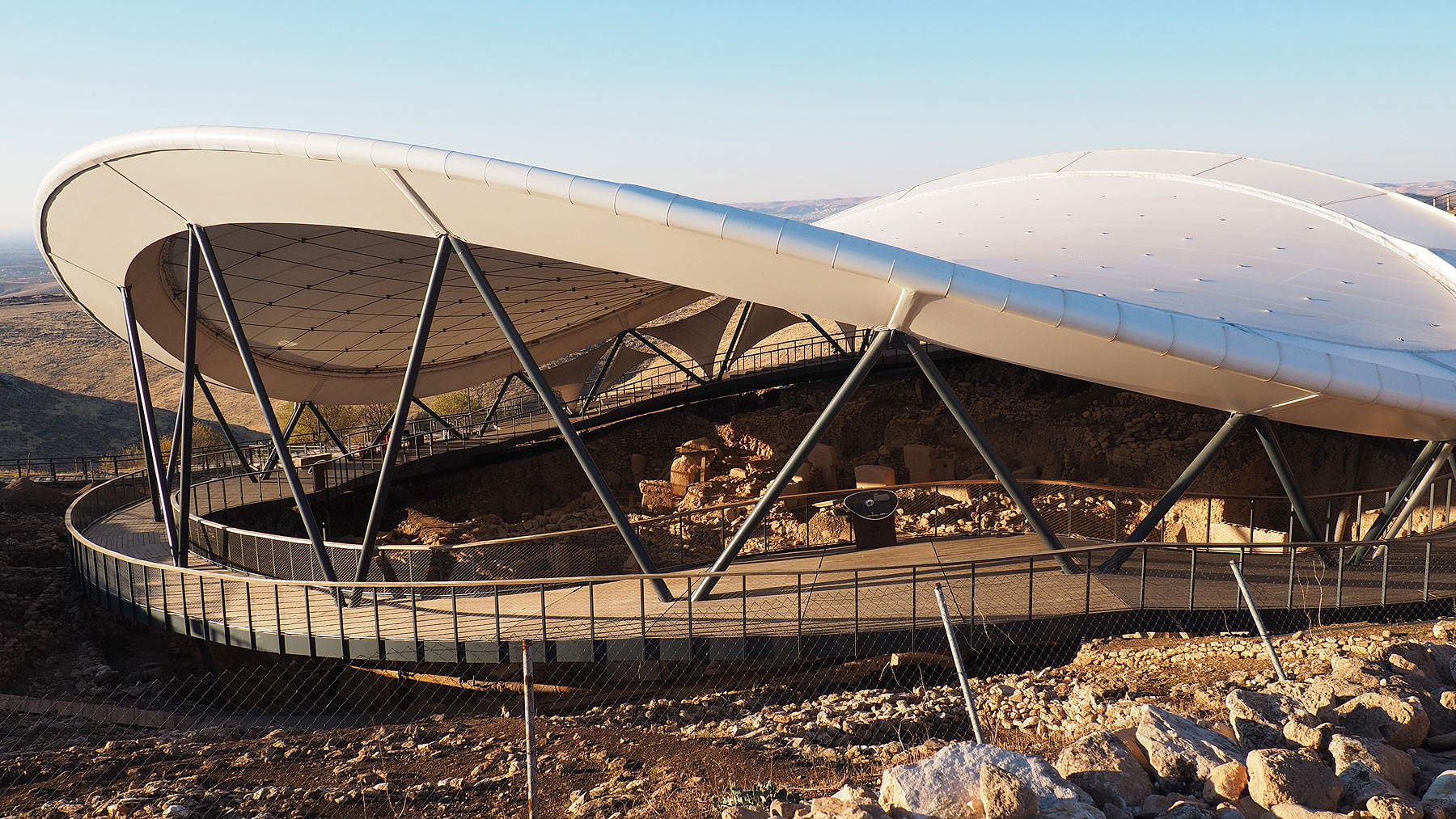

For a number of years now, southeastern Turkey has been preparing to welcome and handle the fast-growing tourist flows expected in the coming years, and much has already been done in this regard: in addition to efficient, technologically advanced and innovative infrastructures designed to enable public enjoyment that is of the highest quality and as risk-free as possible, there is a dynamic and vital network of local guides, translators, tour and cultural workers who cooperate with institutions (primarily Istanbul University and the Archaeological Museum of Şanlıurfa) and man the reception centers set up near the excavation areas. These facilities, true portals of access to the past, are above all symbolic places of mediation between the visitor and the area, characterized by a clean, essential and absolutely environmentally and ecologically compatible design, as well as strategic in respecting the historical value of the area and bringing guests closer to the culture of today’s Turkish people. Those passing through these quiet stations out of time might be invited by a thoughtful native operator to sip a cup of hot çay and savor a slice of Urfa külünçe while waiting for the visit to begin.

The Göbekli Tepe temple, whose construction was started in 9,600 B.C., was unearthed in 1963 by a Turkish-U.S. research team that noticed several piles of flint fragments deposited in the ground, a very clear sign of human presence in the Stone Age. Official excavations began in 1995 under the influential gerence of archaeologist Klaus Schmidt of the University of Heidelberg, in close cooperation with the Archaeological Museum of Şanlıurfa. After Schmidt’s death in 2014, he was succeeded by Professor Necmi Karul of Istanbul University, who to date directs the Göbeklitepe Culture and Karahantepe Research Project and is a member of the Göbeklitepe Scientific Coordination Committee.

Göbekli Tepe is first and foremost monumental, with a perimeter close to 23 meters in diameter and a height varying from 5 to 6 meters, and consists of several oval-shaped buildings. Within each of them, in the center, rise two rectangular “T” shaped pillars that over time have become the universal symbol of the site. The terrain is gently sloping as the temple stands on a hill: a not uncommon practice found at many other sites in the region, built on cliffs and mounds of earth and limestone that dot the face of the Anatolian soil. This is where the toponym Taş Tepeler comes from, which, as anticipated, means “stone hills” in Turkish and indicates precisely this aspect. In addition to natural hills, there are also man-made reliefs in Anatolia that originated from the layering of materials accumulated by human occupation over long periods of time: these are the so-called Tell, a word adopted in English from the Arabic meaning “mound” or “small hill.”

Also in the Taş Tepeler, farther east than Şanlıurfa lies the TekTek mountain range, which is known for the spread of tombstones and mounds built on its heights. One of these is the temple of Karahan Tepe, erected with limestone from the TekTek Mountains, which has the property of being hard on the surface but soft on the inside, very versatile for cutting and working. Karahan Tepe is also estimated to be of pre-Ceramic Neolithic foundation, but according to some recent theories it is older than Göbekli Tepe by a few hundred years. Initially discovered in 1997, it came under the auspices of Istanbul University in 2018, and since 2019 excavations have been chaired by Professor Necmi Karul.

Unlike Göbekli Tepe, this second temple consists of rooms communicating via corridors, stairs, steps and passages in the walls. Elements that, together with the windows, lintels and some rudimentary “furniture” items, make Karahan Tepe a model of experimental architecture that is not yet domestic but already considerably advanced. In and around the perimeter over 250 “T” pillars have been counted, very similar to those observed at Göbekli Tepe.

The Karahan Tepe site includes a large hall reached by a zigzag path that passes around a series of narrow, square rooms. The hall leads toward a pair of adjoining pits that constitute the most interesting rooms: eleven columns emerge from the bottom of the first pit, which according to the most accepted interpretations would represent phallic-shaped totems. From the edge of the pit juts out a mysterious stone human head, with marked and vaguely exotic somatic features: its large, fleshy mouth, wide jaw, and straight, smooth neck evoking the tubular body of a snake enhance its three-dimensionality. With its gaze fixed toward the entrance passage, the head probably greeted those who entered from the main hall, to cross the columns and finally reach the last pit.

The falliform columns suggested the hypothesis that a ritual of initiation, fertility, or a ceremony of passage from childhood to adulthood took place at Karahan Tepe, just as a key-role may have been played by liquids such as water or blood that flowed in a hydraulic channel and dripped into the column pit. The last room seems to be left unfinished: in addition to the presence of a shallow, irregularly shaped pit covering only part of the floor, there is a figure of a fox-headed snake with a thin, undulating body running along the edge of the area. A rather basic style of drawing that, in the artistic context of the temple, may have been the embryonic stage of a much more elaborate work. On the highest level of the floor is a series of small wedges, an element that remains difficult to decipher.

The upright phallus is a widespread leitmotif in the Taş Tepeler, and the recent Sayburç discovery provides yet another piece to the iconographic map of the region. Dated around 8,000 B.C. (an age corresponding to the final phase of Göbekli Tepe) Sayburç has no structural affinities with the larger temples, given its small and architecturally minimal area, but it does in terms of artistic artifacts. From the vertical surface of a stone bench carved within the site emerges a small, full-bodied high relief of a man with a prominent phallus; around it we find animals depicted in the style typical of Göbekli Tepe and Karahan Tepe figures: a bull or buffalo in profile points its large horns toward the carving of a man with a prominent phallus, arms raised and in one hand a snake swaying downward. Further to the right are two leopards encircling the small stone man sideways, who is clutching his sexual organ with both hands. The sculpture wears a necklace very similar to the one engraved on the chest of the famous Urfa Man, a find of unique value in that it represents the oldest sculpture of a human being depicted realistically and life-size. The Urfa Man, also known as the Statue of Balıklıgöl, dates back to around 9,000 B.C. and is currently on display at the Museum of Şanlıurfa, of which it has risen to a symbol and a source of national pride.

Göbekli Tepe also preserves a remarkable collection of human-animal-themed artifacts. Almost all the major pillars of the temple bear high reliefs and bas-reliefs of animals, with decorative signs and symbols. The great wealth of species (wild boars, foxes, panthers, small felines, antelopes, reptiles and spiders, cattle and horses, ducks, and migratory birds) allows us to delve into certain aspects of Neolithic man’s life, such as the study of nature, local fauna, and the seasonality of time: knowledge perhaps developed as practices and strategies related to hunting and adaptation to the environment were refined. In addition to the zoological range, long, thin arms with tiny hands appear on the vertical trunk of many pillars: the visual effect is that of standing before anthropomorphic totems, perhaps erected in favor of deities or oracles. A curious aspect concerns a stele found in a small room north of the temple, which shows the figure of a woman giving birth. The stele is located in the Museum of Şanlıurfa and is rather unusual: if the female gender is itself poorly documented in the Taş Tepeler, the iconography of childbirth in particular has no match at any other site in the area.

The human-animal pair is a widespread theme in the Neolithic. In the Göbekli Tepe temple, animals are portrayed as fierce creatures, alert or in an attack posture; the large totems bear loincloths and belts from which fox fur hangs, traceable to the fox bones inhumed at the base of the pillars. At Göbekli Tepe hovers a sense of menace, of the man-predator’s prevarication over the animal world, or more realistically, a picture emerges in which man seeks to impose himself on his surroundings for survival purposes. In contrast, in Karahan Tepe the animal is supernatural, symbolic or animated by a vitality not conditioned but rather enhanced by man; in Karahan Tepe artifacts the animal may also be a good-natured and harmless creature, as in the majestic sculpture in the Museum of Şanlıurfa that depicts a man with a large leopard on his back with a lazy air, a mocking smile, and teeth that are anything but sharp, rather regular and square like human teeth. The snake also keeps returning in different places and in multiple forms: in the rooms of Karahan Tepe, on the pillars of Göbekli Tepe, in carvings at Sayburç and in many artifacts that have surfaced throughout the Taş Tepeler, hence the idea that the reptile embodied in Neolithic cults a sacred animal or a magical symbol of life, death or sexuality.

To visit the complex of Neolithic sites in Anatolia is to delve into a narrative universe of images, icons, forms and symbols that manifest themselves as signifiers of a universally recognized code, transmitted through time and space. One wonders whether Neolithic man was aware of the potential of artistic creation or, considering the functions for which the sites were intended (public spaces of spiritual gathering for the community, buildings for worship and celebration of rituals, observatories for the sighting of natural phenomena and astronomical events), whether the carvings and sculptures found had essentially decorative, as well as allegorical and magical-propitiatory meanings. At Göbekli Tepe, turning one’s gaze from the graphic detail to the design of the temple in its entirety, one’s thoughts instinctively fly to the astronomical alignment of megaliths, such as Stonehenge, which, however, appeared at least six thousand years later than the Anatolian Tepe (3,100 B.C.-1,600 B.C.).

What we know today is that the Turkic people recognize Göbekli Tepe certainly as a place of confluence of mystical practices, but also devoted to storytelling, preservation of memory and a socio-cultural heritage expressed through languages that predate the formulation of writing. And in this process of transmission of values, time played a key-role, activated by the ingenuity of individuals who, before abandoning their temples of worship and memory, buried them over and over again decades apart under many layers of earth, topsoil, stones and debris that they picked up in the surrounding area and transported all the way to the hills. An amazing feat, to think of it today, probably accomplished by large units of manpower and with tools and technologies unknown to us. Thanks to radiocarbon dating, it was determined that Göbekli Tepe and Karahan Tepe were finally buried and abandoned in the Pre-Ceramic Neolithic B period (8,800-6,500 B.C.).

Whether or not humans were aware of the conservation power of burial is unknown, but twelve thousand years after the Tepe were built, the conservation status of the artifacts is very good, even excellent in the case of the artifacts found intact and preserved at the Şanlıurfa Museum. Yet according to archaeologists, at Göbekli Tepe alone the excavations would have revealed a tiny part, approximately 5 percent, of what was the original temple complex, and there may be many more buildings still buried. Net of the major archaeological discoveries made in Turkey since the early twentieth century, Anatolia indeed remains a vast geographical area that is estimated to conceal underground objects and artistic artifacts still covered by millennia of geological layers. And this is where the Taş Tepeler project gains strength, the aim of which will be twofold: on the one hand to intervene in areas of Turkey that are still unexcavated, and on the other hand to expand research in places that have already been excavated in order to delve deeper into the history and transformations of the Anatolian territory and the indigenous peoples who dwelt there from the 10th millennium B.C. onward.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.