by Ilaria Baratta, published on 12/07/2020

Categories:

Works and artists

/ Disclaimer

The Sansevero Chapel, the temple of Raimondo di Sangro, famous for the presence of Giuseppe Sammartino's celebrated Veiled Christ, is a true treasure of Neapolitan Baroque.

A total immersion in the splendor of Neapolitan Baroque in the heart of the Neapolitan city, this is how the experience could be defined by anyone who visits one of Naples’ best-known monuments: the Sansevero Chapel. A place known to most as the custodian of one of the greatest masterpieces in the history of art, the Veiled Christ, but the Chapel is a true treasure chest of sculptures, marbles and ornaments that leave one enraptured. At the center of the single nave is the Christ, opposite is the white monumentality of the High Altar, and all around, on the side walls, are four round arches that hold sepulchral monuments of the illustrious ancestors of the di Sangro, the family to which the architectural masterpiece belonged. Separating the arches, along with the pillars, are the extraordinary sculptures that constitute the Chapel’s other real treasures, after the Veiled Christ: just think of Disillusionment or Modesty. However, if one looks upward, the wonder is not yet over, for the vault is masterfully decorated in fresco with the Glory of Paradise, with sudden gashes, appearances of angels and illusionistic architectural stratagems. And the whole was complemented by a labyrinthine floor, in part still visible in some parts of the building, such as near the tomb of Raimondo di Sangro, the one to whom we owe the 18th-century appearance of the Chapel (the iconographic layout that has come down to us), but especially in the numerous remains in the museum’s storage room.

As early as 1688, thus before the “remodernization” by the aforementioned Raimondo, Pompeo Sarnelli described in his Guida de’ forestieri, curiosi di vedere, e d’intendere le cose più notabili della regal città di Napoli, e del suo amenissimo distretto, the church of Santa Maria della Pietà de’ Sangri (otherwise called Pietatella) as follows: “is greatly embellished with works of the finest marble, around which are the statues of many worthy personages of that family with their eulogies,” placed “against the small, and lateral door of San Domenico Maggiore,” and founded by “Alessandro di Sangro Patriarch of Alexandria, and Archbishop of Benevento out of devotion to the Mother of God.”

|

| Naples, Sansevero Chapel. Ph. Credit Sansevero Chapel Museum |

|

| Naples, the Sansevero Chapel. Ph. Credit Sansevero Chapel Museum |

|

| Naples, the Sansevero Chapel. Ph. Credit Sansevero Chapel Museum |

|

| Naples, the Sansevero Chapel. Ph. Credit Sansevero Chapel Museum |

|

| Naples, the Sansevero Chapel. Ph. Credit Sansevero Chapel Museum |

According to legend (many legends are linked to the history of the Sansevero Chapel and to Raimondo himself), it happened that an innocent man, but condemned to be locked up in a prison, saw a portion of the garden wall of the di Sangro family’s palace in Piazza San Domenico Maggiore collapse and the image of the Madonna appear as he was being dragged in chains to prison: it happened in the late 16th century. The man, as a sign of mercy, promised Our Lady to give her a silver lamp and an inscription if he was released from prison and declared innocent. So it happened, and the sacred image of the Virgin began to be visited by pilgrims, who in turn received numerous other graces. Among these miracles, it is said that even the duke of Torremaggiore, Giovan Francesco di Sangro, was the protagonist of an episode: seriously ill and turning to this effigy of Our Lady to ask her to make him well, he came back healthy and therefore had a small chapel dedicated to Santa Maria della Pietà erected, right on the spot where the Virgin had appeared to the innocent man. Later, in the early seventeenth century, Giovan Francesco’s son, Alessandro di Sangro, patriarch of Alexandria, initiated significant enlargements and alterations to the original Pietatella as a sign of thanksgiving for his father’s recovery: he built a true building of devotion intended to house the tombs of the dynasty’s ancestors, as well as future exponents. The intention was precisely to welcome and reunite the members of the di Sangro family in one place, the same place where his father had been saved. Little remains of the Chapel’s17th-century appearance: basically, only the exterior structure, the polychrome decoration of the apse, and four mausoleums in the side chapels. The interventions made by Alexander and the intent behind them are still testified to this day by theinscription visible on the main door: “Alexander of Sangro patriarch of Alexandria destined this temple, raised from the foundations to the Blessed Virgin, as a sepulcher for himself and his own in the year of the Lord 1613.” This is not the only inscription in the monumental chapel to testify to part of its history: in fact, on the side door one can read another long inscription, which in this case dates back to the 18th century, in which, addressing the visitor directly, the glorious phase that saw Raimondo di Sangro (Torremaggiore, 1710 - Naples, 1772), another exponent of the family, is recounted. “Whoever you are, O wayfarer, citizen, provincial or foreigner, enter and devoutly pay your respects to the prodigious ancient work: the noble temple long since consecrated to the Virgin and majestically amplified by the ardent prince of Sansevero Don Raimondo di Sangro for the glory of his ancestors and to preserve to immortality his ashes and those of his own in the year 1767. Observe with attentive eyes and with reverence the urns of the heroes honored with glory and contemplate with wonder the praiseworthy homage to the divine work and the sepulchres of the deceased, and when you have rendered the honors due deeply reflect and depart”: with these words anyone who enters is greeted. It was in fact in the middle of the eighteenth century that the seventh prince of Sansevero carried out the extraordinary work that we still see today: its present appearance is in fact the result of the latter’s desire to build a great temple that would glorify all the members of his family. Although, as attested by the words of Pompeo Sarnelli, already in the seventeenth century the chapel was enriched with many marbles and statues, with Raimondo’s rearrangement the Baroque exploded in every corner and detail: he commissioned from the leading sculptors of the time the statues placed near the pillars between the arches, which in the complex iconographic layout were to represent the Virtues, as well as the absolute masterpiece, namely the Veiled Christ, and from the most skilled painters the magnificent Glory of Paradise decorating the vault.

|

| Carlo Amalfi and Ferdinando Vacca, Portrait of Raimondo di Sangro (c. 1747-1750; engraving) |

Raimondo was a rather irreverent exponent of the di Sangro family: he used to try his hand at experiments, as he was very skilled in mechanics, hydrostatics, pyrotechnics, and military architecture. Among these, in the second volume of Giangiuseppe Origlia’sIstoria dello Studio di Napoli , a seminal text published in the mid-eighteenth century through which we learn about Raimondo’s detailed biography, inventions such as a peculiar arquebus that operated on both powder and compressed air, a cannon that was more light, a floating carriage, a type of wax and a type of silk made from plant species, prodigious medicines, artificial gemstones, a folding stage, and other oddities that aroused wonderment from citizens and foreigners alike. A creative and lively mind capable of giving birth to extraordinary reveries that he punctually realized. In addition to these subjects, he possessed a great knowledge of languages, literature and philosophy. In 1737 he was inducted among the gentlemen of the chamber of King Charles III of Bourbon, and three years later, in 1740, he was made a knight of the Order of San Gennaro. He was also a valiant military man: he became colonel of the Capitanata regiment and took part in the war of Velletri, proving his courage. Then in 1751 his most famous literary work was published, the Lettera Apologetica: an apologia on an ancient communication system used by the Incas of Peru. These were quipu, or knots made of colored cords by means of which this population narrated events and stories. In reality, the text was a tool for Ramon to convey free thought on topics such as the origin of the world and man, the Church whose unnecessary meddling he did not tolerate, and the Inquisition Tribunal. These themes were considered to be expressions of Freemasonry, to which di Sangro himself was considered to be linked. For this reason the Lettera Apologetica entered the forbidden books and was condemned by the Church and its author considered an exponent ofesotericism, as well as Grand Master of Freemasonry. A real myth was created around him because of his prodigious ingenuity and his being “a wonderful man predisposed to all the things he dared to undertake,” as his tombstone reads. Ramon’s unusual personality gave rise to numerous legends about both himself and the Chapel. The latter, and in particular its dungeons, became in the imagination an almost demonic place, since at night dull, incessant noises like that of a hammer on an anvil could be heard and infernal glows could be seen from the large windows. According to one belief, Ramon even committed murders: he had two of his servants killed to embalm their bodies in order to make the Anatomical Machines, he killed seven cardinals to make chairs out of their bones and skin, and again according to one legend, he blinded Giuseppe Sanmartino (Naples, 1720 - 1793), sculptor of the Veiled Christ, so that he would not allow him to make another masterpiece like that. And again, that through an alchemical process he succeeded in marbling the veil of the Christ.

It is also said that at the time of his death, the prince of Sansevero resourced and had a Moorish slave cut himself into pieces in order to fit well into a chest, from which he would emerge healthy at a given time; the di Sangro family, however, searched for the chest, uncovered it, and the corpse tried to get up but immediately fell down, uttering a howl of damnation. Even today, many demonic legends surround the prince, and there are even tales of close encounters with his spirit. In light of all this, the true meaning of the iconographic project that Ramon wanted to create in the Chapel through the marble sculptures is still unknown, but it has nevertheless often been likened to Freemasonry, to an initiatory project.

Camillo Napoleone Sasso ’s description of it in the mid-nineteenth century in his Storia de’ monumenti di Napoli e degli architetti che gli edificavano dal stabilimento della monarchia, fino al nostro giorno largely mirrors the current one: as narrated in the nineteenth-century description, it is a “little temple worthy to be seen for the excellent works of sculpture therein, directed by the most feracious ingenuity of Raimondo di Sangro,” and “many noble and sumptuous Sepulchres with beautiful statues are seen.” The sepulchral monuments are placed in the side chapels and house the illustrious ancestors of the family, while the sculptures located between the arches are dedicated to the women of the family, with the exception of Disenchantment, which is intended to pay homage to Raimondo’s father, Antonio. The latter, emblems of the Virtues, would presumably constitute, starting from the entrance, an initiatory path to lead to the knowledge of the soul, and the complexity of achieving it was further emphasized by the labyrinthine floor that the visitor would find himself walking along. In devising the statues of the Virtues, the Prince of Sansevero was influenced by Cesare Ripa’sIconologia, which he must certainly have known well, since he also financed a five-volume reissue of the late 16th-century text.

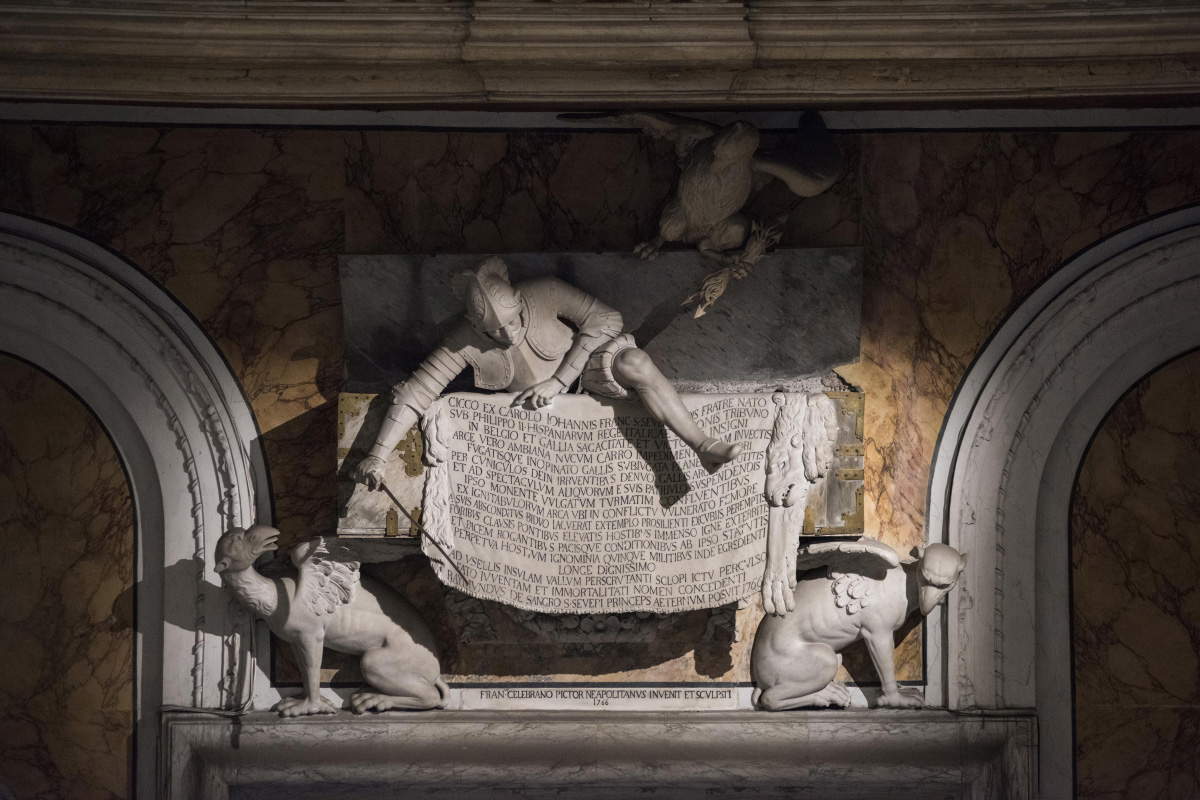

“Above the door of the church is the deposition of one di Sangro who armed with helmet and armor comes out with sword in hand from an iron chest,” Sasso writes: this is Cecco di Sangro, a commander in the service of Philip II, who during a campaign in Flanders remained hidden for two days in a chest to defeat his enemies and seize the fortress of Amiens. The work by Francesco Celebrano (Naples, 1729 - 1814) begins the glorification of the family that is accomplished within the Chapel and has been considered by many to be a kind of immortal guardian of the Masonic temple.

|

| Francesco Celebrano, Monument to Cecco di Sangro (1766; marble; Naples, Sansevero Chapel). Ph. Credit Sansevero Chapel Museum |

|

| Francesco Celebrano, Monument to Cecco di S angro (1766; marble; Naples, Sansevero Chapel). Ph. Credit Sansevero Chapel Museum |

|

| Giuseppe Sammartino, Veiled Christ (1753; marble, 180 x 80 x 50 cm; Naples, Sansevero Chapel). Ph. Credit Sansevero Chapel Museum |

|

| Giuseppe Sammartino, Veiled Christ (1753; marble, 180 x 80 x 50 cm; Naples, Sansevero Chapel). Ph. Credit Sansevero Chapel Museum |

|

| Giuseppe Sammartino, Veiled Christ (1753; marble, 180 x 80 x 50 cm; Naples, Sansevero Chapel). Ph. Credit Sansevero Chapel Museum |

From the entrance, walking toward the High Altar, decorum, Liberality, Zeal of Religion, Suavity of the Conjugal Yoke, and Modesty follow on the left; past the monumental High Altar and back toward the entrance, Disillusionment, Sincerity, Self-Reliance,Education, andDivine Love follow. Sculptural masterpieces depicting as mentioned the Virtues that were made by artists such as Antonio Corradini (Venice, 1668 - Naples, 1752), Francesco Queirolo (Genoa, 1704 - Naples, 1762), Fortunato Onelli, Paolo Persico (Sorrento, 1729 - Naples, 1796).

Decorum is personified by a naked young man wearing a lion skin on his hips and leaning on a column placed at his side topped by the feline’s head, symbolizing the victory of the human spirit over wild nature. Liberality is a refined female figure holding a cornucopia full of jewels and valuables in her left hand and coins and a compass in her right hand. At her feet is an eagle. The statue is set before one of the four faces of a pyramid (the other three are related to the Suavity of the Marital Yoke, Sincerity andEducation). Presumably the geometric figure symbolized in Ramon’s initiatory iconographic setup Egyptian wisdom.

The Zeal of Religion is presented as a more complex sculptural group: an elderly man holds the light of Truth in one hand and a whip in the other; with one foot he treads on a book from which some snakes come out and bite a cherub. The latter is destroying heretical texts, while two other putti lift a medallion on which are depicted the faces of two women, the wives of Giovan Francesco di Sangro. One woman personifies the Suavity of the Marital Yoke: she holds a feathered yoke and lifts two flaming hearts, while a winged putto lifts a pelican in one hand. The bird symbolizing Christ’s sacrifice on the cross refers toalchemy: it is emblematic of a particular vessel used for distillation and also of the philosopher’s stone.

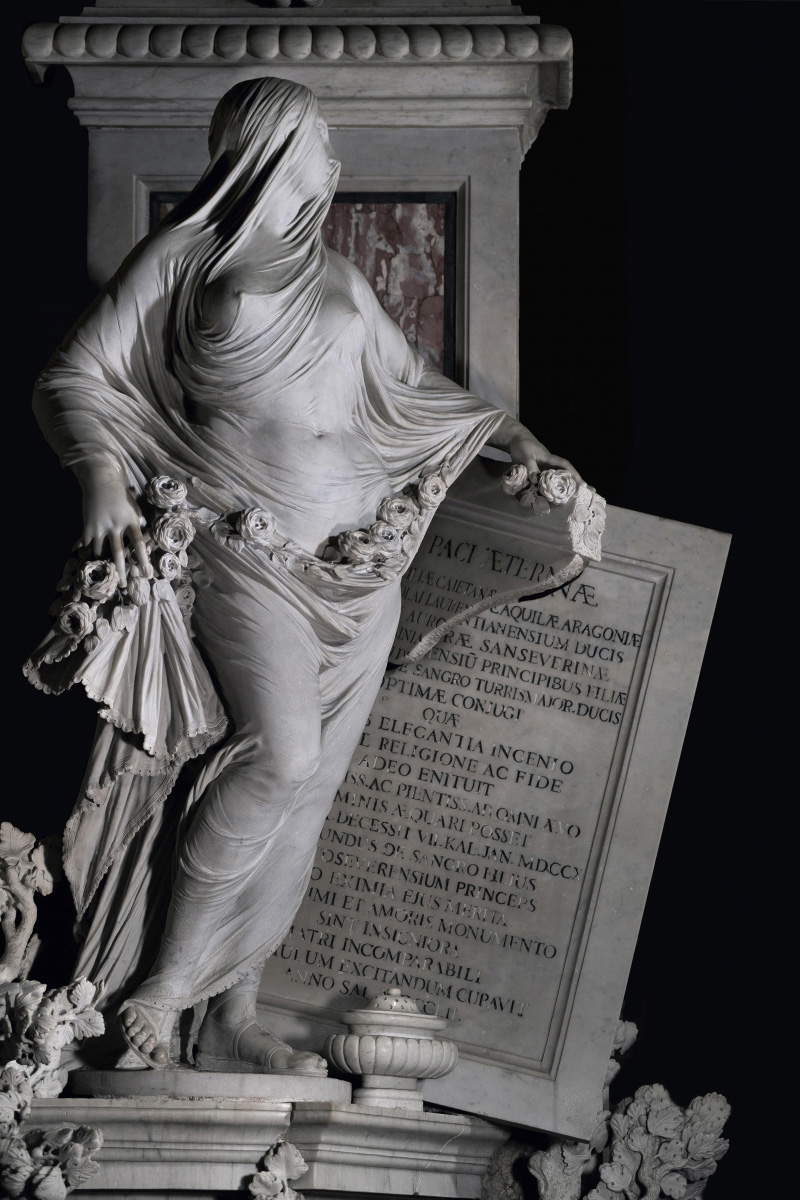

Sincerity is dedicated to Carlotta Gaetani, Raimondo’s wife: depicted gracefully, the woman holds a heart and a caduceus in her hands, and at her feet is placed a putto with two doves (in alchemy, the state of raw matter before it becomes the philosopher’s stone); the caduceus, on the other hand, is a symbol of the union of opposites. A warrior holding a lion in chains represents Self Domination, the control of one’s passions-a typical theme in Freemasonry. Added to the subject are two cherubs and a medallion with the face of Raimondo’s grandmother, Geronima Loffredo.Education is depicted by a woman teaching a young boy, who in turn has Cicero’s De officiis in his open hands. Finally,Divine Love has the face of a cloaked youth raising a flaming heart, a reference to the fire the alchemist receives from God. Elements related to alchemy, to Freemasonry, are thus discernible in most of the statues of the Virtues. However, the sculptures of great significance in terms of both quality and meaning are placed on either side of the High Altar: on one side is Modesty and on the other is Disillusionment. The first represents Ramon’s mother, “covered with a transparent veil under which all the features of the body are revealed,” as we read in the Storia de’ monumenti di Napoli (History of the Monuments of Naples); the second represents the prince’s father, in the features of “a man enveloped in a net from which he tries to extricate himself with the help of his own strength. The net stands almost entirely isolated without touching the statue. It is to be observed the attitude of the man who tries to get out of the net to conclude being this a non plus ultra among the works of art,” as Sasso relates. In his greatest masterpiece, the Disenchantment, Francesco Queirolo masterfully renders a man’s attempt to free himself from sin through the net in which he is entangled, aided by a winged genie: the male figure is lifting the net off his head and has already freed his right arm and chest. The young helper points the man to a globe and the Bible, symbolizing worldly passions and the sacred, respectively, and on the base of the sculptural group is visible a bas-relief depicting Jesus giving sight to the blind man, an episode that well expresses the intent of the sculpture. When Raimondo’s mother died prematurely, his father began to take up a profligate life, traveling throughout Europe, but by now an old man he returned to Naples, repented of his mistakes and dedicated the last years of his existence to his faith. There is no other comparable sculpture in the history of art: the invention of the net wrapped around the body is an extraordinary example of virtuosity that the artist was able to accomplish with marble. If the net of Disenchantment affirms the great skill in mastering a material such as marble, the veil that covers the entire figure of Modesty, including her face, is no less impressive. The woman elegantly turns her gaze in profile, revealing under the veil the refined face, and carries roses on her lap in the folds of the fabric. The transparent veil is finely modeled on the body and emphasizes the perfection achieved by the statue’s author, Antonio Corradini. Symbolizing by some expedients, such as the broken tombstone and the lost gaze, the untimely death, a depiction of the veiled goddess Isis, a deity belonging to the initiatory world, has been seen in the woman.

|

| Antonio Corradini, Decoro (1751-1752; marble; Naples, Sansevero Chapel). Ph. Credit Sansevero Chapel Museum |

|

| Francesco Queirolo, Liberality (1753-1754; marble; Naples, Sansevero Chapel). Ph. Credit Sansevero Chapel Museum |

|

| Fortunato Onelli, Francesco Celebrano and others, Zeal of Religion (1767; marble; Naples, Sansevero Chapel). Ph. Credit Sansevero Chapel Museum |

|

| Fortunato Onelli, Francesco Celebrano and others, Zeal of Relig ion (1767; marble; Naples, Sansevero Chapel). Ph. Credit Sansevero Chapel Museum |

|

| Paolo Persico, Suavità del giogo coniugale (1768; marble; Naples, Sansevero Chapel). Ph. Credit Museo Cappella Sansevero |

|

| Antonio Corradini, Modesty (1752; marble; Naples, Sansevero Chapel). Ph. Credit Museo Cappella Sansevero |

|

| Antonio Corradini, Pudicizia (1752; marble; Naples, Sansevero Chapel). Ph. Credit Museo Cappella Sansevero |

|

| Francesco Queirolo, Disillusionment (1753-1754; marble; Naples, Sansevero Chapel). Ph. Credit Museo Cappella Sansevero |

|

| Francesco Queirolo, Disenchantment (1753-1754; marble; Naples, Sansevero Chapel). Ph. Credit Museo Cappella Sansevero |

|

| Francesco Queirolo, Sincerity (1754-1755; marble; Naples, Sansevero Chapel). Ph. Credit Museo Cappella Sansevero |

|

| Francesco Celebrano, Self-domination (1767; marble; Naples, Sansevero Chapel). Ph. Credit Sansevero Chapel Museum |

|

| Francesco Queirolo, Education (1753; marble; Naples, Sansevero Chapel). Ph. Credit Museo Cappella Sansevero |

|

| Francesco Queirolo (?), Divine Love (second half of the 18th century; marble; Naples, Sansevero Chapel). Ph. Credit Sansevero Chapel Museum |

A veil also covers the most famous masterpiece of the entire Chapel, as well as among the most famous in the history of art, which attracts numerous visitors from all over the world: the Veiled Christ, the marble work that Giuseppe Sanmartino created in the mid-18th century. Sasso described it as "a sculpture in which this excellent craftsman surpassed himself. Dictating a dead Christ lying on the bier, it is covered with a transparent veil, like the Modesty which he set out to imitate, but which in the judgment of the connoisseurs surpassed him. One admires in it not only the transparency of the veil, but the artificial negligence of the sheet where the Divine Corpse rests and the expressive posture of the statue seeming truly a dead man." Sanmartino sculpted the life-size body of the dead Christ , covered by a transparent veil, and what is extraordinary is that he did it in a single block of marble. The folds of the veil, through which all the features of the body are perceived, are the result of such perfect sculptural skill that they seem to be of another material, of a palpable fabric. She manages to embroider marble, to give a feeling of softness to the material. So much so that, as already stated, legend runs that the veil was created by Raimondo di Sangro through an alchemical process of marbling.

The lifeless body of Christ, as if to link this with Sanmartino’s masterpiece, is depicted in an immediately preceding episode, namely the Deposition, in theHigh Altar. Here the Baroque takes center stage with volumes and forms that seem to spill out and with expressions of theatricality. As theatrical is the fresco on the vault created by Francesco Maria Russo: in the Glory of Paradise, where light and illusion dominate, the dove of the Holy Spirit crowned with a triangular-shaped nimbus, the geometric figure of the Worshipful Master in Freemasonry, plays a significant role.

|

| Giuseppe Salerno, Anatomical Machines (ca. 1756-1764; Naples, Sansevero Chapel). Ph. Credit Sansevero Chapel Museum |

Initially, the Veiled Christ was supposed to have been destined for the underground Cavea, a sort of cave below the main nave that would have housed the tombs of the family’s ancestors; the sepulchral project was not realized as conceived by the prince, but today the room houses, inside two vitrines, the Anatomical Machines: two skeletons, one male and the other female, standing upright, which have perfectly preserved the entire circulatory system. Even, a fetus was visible until recently. The anatomical systems were carried out by physician Giuseppe Salerno, but the legend still remains that the prince had two of his servants killed and embalmed, partly because Ramon used to carry out experiments in the medical field as well, as mentioned above.

The figure of the prince of Sansevero is one of the most enigmatic and shrouded in mystery, mainly as a result of the many legends surrounding him: immortal he still stands vigil in his Chapel in his sepulchral monument, which is accessed from the third arch on the left. His portrait scrutinizes, after centuries, anyone who comes to pay homage to him, topped by symbols celebrating his military activity, scientific experiments and literary passion: all the things he dared to undertake and for which he was remarkably predisposed.

Essential Bibliography

-

Aurelio De Rose, Naples. The Sansevero Chapel, Rogiosi, 2016

-

Enrico Facco, Premortal Experiences. Science and consciousness on the border between physics and metaphysics, Edizioni Altravista, 2010

-

Oderisio De Sangro, Raimondo de Sangro and the Sansevero Chapel, Bulzoni, 1991

-

Camillo Napoleone Sasso, Storia de’ monumenti di Napoli e degli architetti che gli edificavano dal stabilimento della monarchia sino ai nostri giorni, Vitale, 1856

-

Pompeo Sarnelli, Guida de’ forestieri, curiosi di vedere e d’intendere le cose più notabili della regal città di Napoli e del suo amenissimo distretto, 1688

The author of this article: Ilaria Baratta

Giornalista, è co-fondatrice di Finestre sull'Arte con Federico Giannini. È nata a Carrara nel 1987 e si è laureata a Pisa. È responsabile della redazione di Finestre sull'Arte.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.