For Eleonora Luciano, in memoriam.

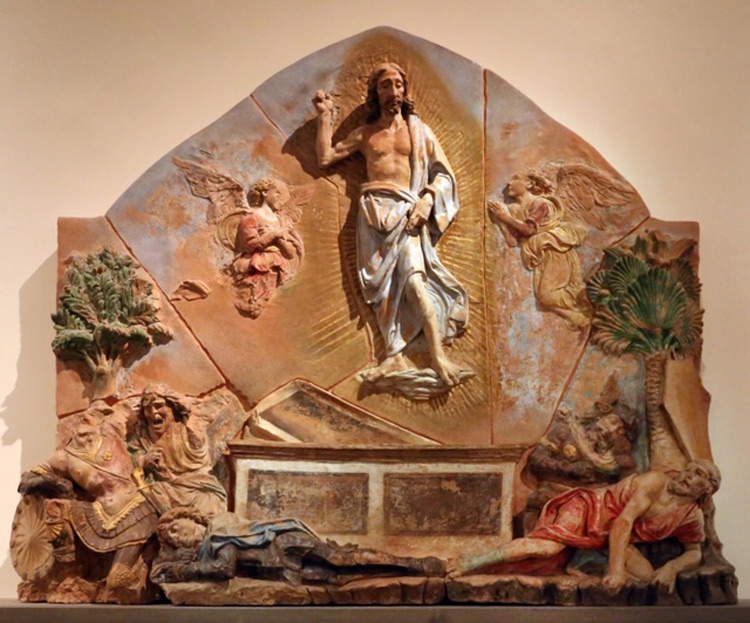

“One of the most astonishing sculptures of the Florentine second half of the 15th century” (Caglioti in Florence 1992, p. 171), the Resurrection of Christ by Andrea del Verrocchio (Florence, 1435 - Venice, 1488) is not present in the exhibition itinerary of the Palazzo Strozzi exhibition, Verrocchio, Leonardo’s Master, and (let it be noted) is also almost completely absent from the essay on the artist’s sculptural production. The work, in fact, due to its precarious state of preservation and the fragile material of which it is composed, could not leave the hall of the Museo Nazionale del Bargello, where it is still located, nor to reach Palazzo Strozzi, the main exhibition venue, nor to go down a few floors and compare with the other busts of Christ, derivations from that of theIncredulity of St. Thomas for Orsanmichele, the artist’s bronze masterpiece. Still, this polychrome terracotta relief is of extraordinary interest for a variety of reasons, and it is hoped that the reader of this article will wish to continue the visit to the Bargello exhibition precisely by going up to the room where, as a rule, the Lady with a Small Bouquet is also displayed, these days in the first room of the Strozzi exhibition.

The rediscovery of the Resurrection was no less surprising than the relief itself: “no other terracotta relief of the fifteenth century carries with it a comparable measure of vitality” (Butterfield 1997, p. 86). When it was found in the early twentieth century by Carlo Segré, the then owner of the Medici villa at Careggi, in the attic of the same villa, the relief was broken into more than sixty pieces. It was later reassembled, inserted into a frame and placed inside the villa’s central courtyard. Despite the numerous losses, the subject of the relief was perfectly legible and its attribution to Verrocchio was, from then on, widely accepted (Butterfield 1997, p. 214).

The theme of the relief is the Resurrection of Christ, according to what, on the surface, might appear to be a traditional iconography. At the center of the relief is the magnificent figure of the Risen One, triumphant over death and flanked by two angels in flight and prayer. Below the mentioned scene and closer to the observer are the five soldiers in charge of guarding the tomb. They are arranged around an open sarcophagus, three of them awake and rising from the clamor, two still placidly asleep. The setting of the scene is suggested by the narrow strip of barren land in the foreground and two symmetrical trees (a palm and a cedar of Lebanon, Caglioti in Florence 1992, p. 173) on the sides.

|

| Andrea del Verrocchio, Resurrection of Christ (c. 1470; polychrome terracotta, 135 x 158 x 30 cm; Florence, Museo Nazionale del Bargello). Ph. Credit Francesco Bini |

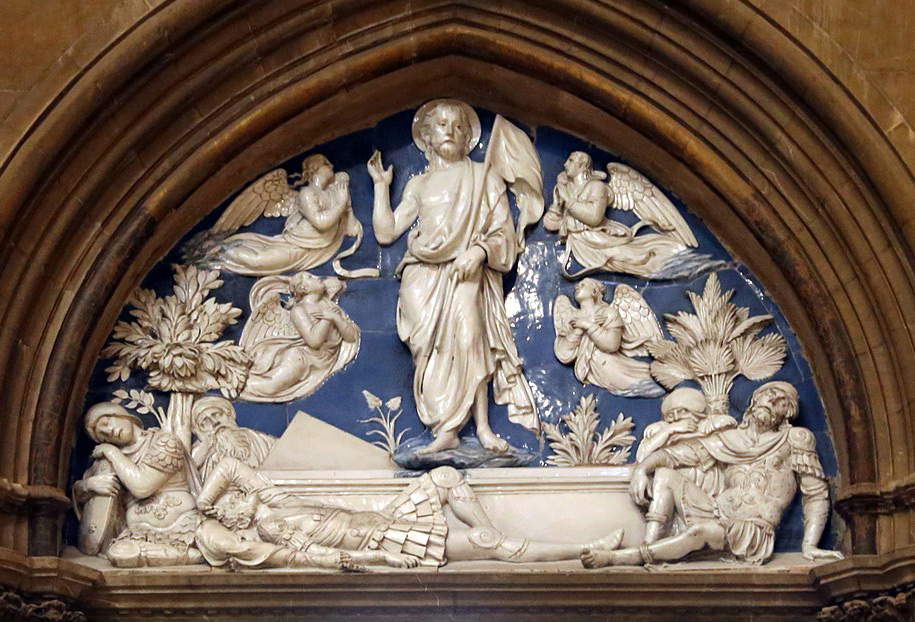

Since its discovery, many scholars have recognized the derivation of Verrocchio’s relief from a famous and prestigious prototype, represented by the glazed terracotta of 1442-45 by Luca della Robbia (Florence, 1399/1400 - 1482), which is still found in the lunette above the entrance door to the north sacristy of Florence cathedral (Gamba 1904, p. 60). Despite the many similarities with the Verrocchio derivation, Andrew Butterfield, curator of an upcoming U.S. exhibition on Verrocchio to be held at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., from Sept. 15, 2019 to Jan. 12, 2020, noted how the terracottas are actually based on two different sources. In fact, it is only in the account of the Resurrection as reported by the Acts of Pilate, an apocryphal text, that the guards wake up and witness the miracle; on the other hand, in the robbiana of Santa Maria del Fiore, all the soldiers are asleep. Verrocchio may have been asked to conform the scene to the above-mentioned text, widely used in sacred representations, popular celebrations and also representing the Resurrection, and certainly owned by the Medici family, a member of which was, no doubt, the commissioner of this relief (Butterfield 1997, p. 83, but also Covi 2005, p. 31 note 7).

In fact, this Resurrection is most likely to be identified with the “story of relief chom più figures,” reported as the fifth item in the 1496 inventory presented by Verrocchio’s half-brother Tommaso to the Officers of the Republic, charged with honoring the debts of Piero di Lorenzo de Medici. Moreover, an addition in the margin to this and the next two lines declares “per a Charegi,” elucidating the reader as to its first destination (the other two objects were the Putto with dolphin and another figure crowning a fountain, likely lost). More difficult to define is the exact location the terracotta had within the Medici villa at Careggi. For the religious subject, the villa’s chapel has always seemed the most likely place of destination, and it has long been believed to have been placed above its entrance door, on the outer side and on the courtyard (Rohlmann in Florence 2008, p. 94, which reports all opinions in favor of this reconstruction). Its problematic absence from the inventory compiled after Lorenzo the Magnificent’s death in 1492 has already been convincingly explained in the past by Francesco Caglioti, noting the immovability and consequent inalienability of this object, firmly walled in a wall (Caglioti in Florence 1992, p. 171).

More recently, Rohlmann has proposed identifying the Resurrection as the summit lunette of the Deposition of Christ by Rogier van der Weyden (Tournai, 1399/1400 - Brussels, 1464), formerly in the Villa chapel and now in the Uffizi (Rohlmann in Florence 2008, p. 95; for the Careggi chapel, Lillie 1998, pp. 91-92). Such an identification would be corroborated, according to the scholar, by an inventory of 1482 where the altarpiece in the chapel (erroneously described, but, most likely, the aforementioned Deposition ) is said to be surmounted by a “pictura della risurrectione” (Rohlmann in Florence 2008, p. 96 and Warburg 1932, I, p. 211). Although we speak of a painting instead of a relief (a rather common error in fifteenth-century inventories), if this identification turns out to be correct, the altarpiece and the relief would have been united by the theme, the last moments of Christ’s life, and by the same vivid colors (more problematic to accept, however, would be the dating, which, for both works, would fall, according to Rohlmann, in the early 1560s). The difference in length between the painting and the overlying terracotta may perhaps have been obviated by a massive architectural frame, also described in the 1482 inventory.

|

| Luca della Robbia, Resurrection of Christ (1442-45; glazed terracotta, 200 x 260 cm; Florence, Santa Maria del Fiore) |

|

| Rogier van der Weyden, Deposition of Christ in the Tomb (c. 1450; oil on panel, 96 x 110 cm; Florence, Uffizi Galleries) |

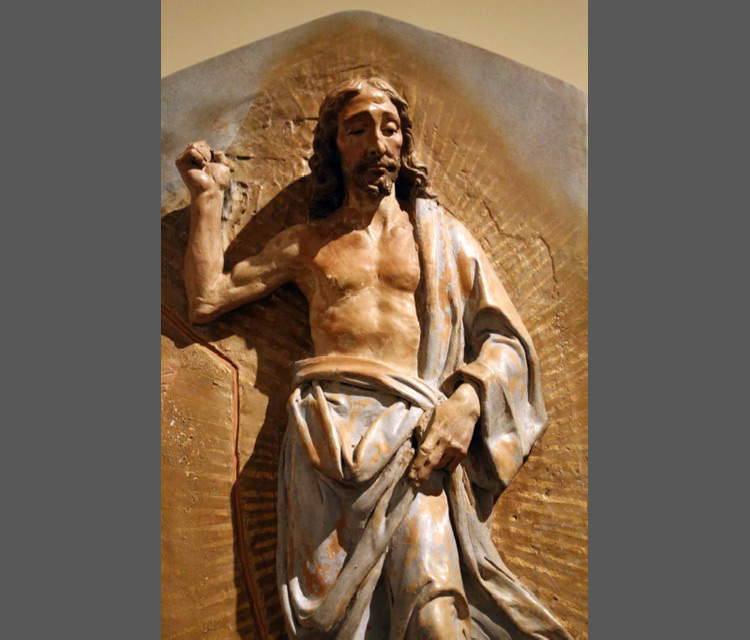

Essential for a proper evaluation of the work is, then, the role played by natural light in its fruition in ancient times. Whether the lunette had been inside the chapel or outside it, light would certainly have contributed to the overall narrative effect and evocative power of the relief. In fact, Andrea not only offered a broad sampling of emotions, through the different reactions of the soldiers to the miracle, but, by hollowing out the back of all the figures in the foreground, he caused them to cast shadows, thus amplifying the (fictitious) brightness of Christ’s body. Such a technical stratagem was certainly designed to suggest the idea of a radiance of light coming directly from the body of Christ, to which the most damaged figure in the relief, on the far left, who most likely covered his face with a bent and destroyed arm, must have referred (Butterfield 1997, p. 213).

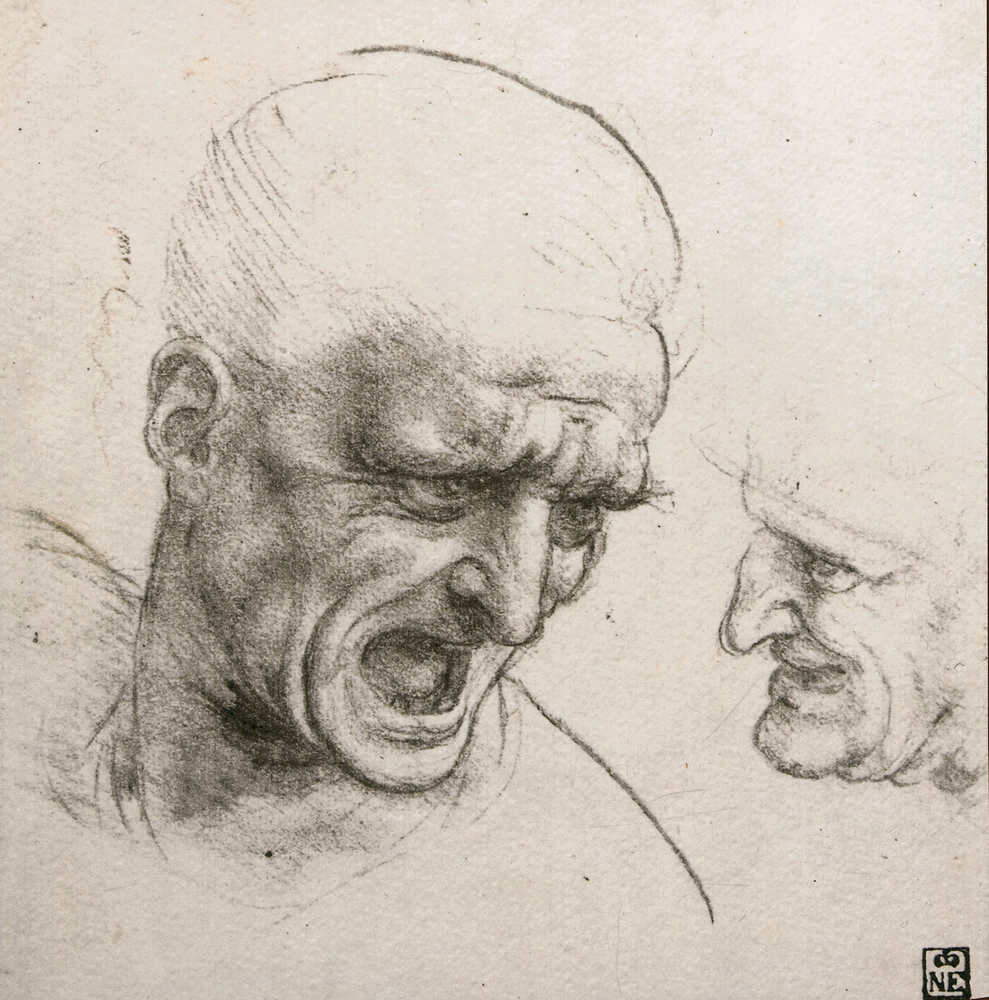

The treatment of the drapery and the sense of realism that characterizes the relief has led some scholars, including Gamba, Planiscig, Serros, and Covi, to give the work an early date; others, including Valentiner, a more mature Gamba, Pope-Hennessy, and Dolcini, have proposed, instead, one in the late 1970s or early 1980s. While broader draperies replaced the heavy ones that cling to the bodies of the characters in the Resurrection, Verrocchio’s later production was also characterized by a greater idealization of the figures (Covi 1968; idem 1972; idem 2005). Due to the absence of documentation, several scholars have, therefore, tried to date the terracotta by establishing stylistic comparisons with works whose dating is less problematic. Both Caglioti and Butterfield, in their writings in the 1990s, emphasized the stylistic proximity between this Christ, that of theIncredulity of St. Thomas and the Forteguerri cenotaph in Pistoia, the latter two commissions begun during the 1970s (Caglioti in Florence 1992, p. 171 and Butterfield 1997, p. 214). While Butterfield proposed the early years of the decade, Caglioti looked to the Pazzi Conspiracy as the closest chronological reference for the work’s origin; in any case, both dates would endorse the presence of Leonardo da Vinci (Florence, 1452 - Amboise, 1519) within Verrocchio’s workshop and his involvement in the making of the relief (Caglioti in Florence 1992, p. 171 and Butterfield 1997, p. 82). It was Valentiner first, followed later by Schottmüller in 1933, who glimpsed Leonardo’s involvement in the execution of the relief, while Passavant in 1969 went so far as to attribute the entire sculpture to Verrocchio’s most talented pupil. In the absence of further evidence to corroborate the presence of Leonardo’s hand as a “sculptor,” it will be possible in any case to note that his interests in physiognomy, in theexpression of the affections and for the strong characterization of his characters may have originated (or at least found strong stimuli) precisely within the atelier of his master, who was not only the executor but also the corrector, supervisor and director of the very extensive polymateric production that came out of his workshop. On the other hand, the comparison between Verrocchio’s figure of the screaming soldier and the analogous figure in Leonardo’s drawing, now in Budapest, for the Battle of Anghiari has been repeatedly put to value.

|

| Andrea del Verrocchio, Resurrection of Christ, detail with the figure of Christ. Ph. Credit Francesco Bini |

|

| Andrea del Verrocchio, Resurrection of Christ, detail with the two soldiers on the right. Ph. Credit Francesco Bini |

|

| Andrea del Verrocchio, Resurrection of Christ, detail with one of the soldiers on the left. Ph. Credit Francesco Bini |

|

| Andrea del Verrocchio, Resurrection of Christ, detail with the shouting soldier. Ph. Credit Francesco Bini |

|

| Leonardo da Vinci, Study for the Battle of Anghiari, (1503-05; black chalk on paper 181 x 198 mm; Budapest, Szépművészeti Múzeum) |

The opinion, already expressed by Caglioti in 1992, has not found further development either in the catalog essay by the same author or in the card prepared by Ilaria Ciseri, but it seems that a correct stylistic framing of the work can be entrusted precisely to the “voice” of the first scholar: “if the folding of the cloths is mindful of the dryness of Desiderio, if the conduct of some parts does not always support the impetus of the imaginative, it remains only to contemplate a broad delegation of the master burdened with pupils, among whom Leonardo excelled” (Caglioti in Florence 1992, p. 171). It remains to be explained why, in the light of the new attribution to the young Leonardo of the Madonna and Child, already Rossellini’s, the scholar has not established a relationship with the early grappling with clay that he himself acknowledged, in the past, in the Bargello relief.

The proposal is particularly suggestive and we would be very sorry if the professor had changed his mind.

Bibliography

Butterfield 1997

Andrew Butterfield, The sculptures of Andrea del Verrocchio, New Haven, 1997.

Covi 1968

Dario A. Covi, “An unnoticed Verrocchio?”, The Burlington Magazine, vol. 110, 1968, pp. 4-9.

Covi 1972

Dario A. Covi, "Review of Gunter Passavant, Verrocchio, London, Phaidon, 1969," Art Bulletin, vol. 54, no. 1, 1972, pp. 90-94.

Covi 2005

Dario A. Covi, Andrea del Verrocchio: life and work, Florence, 2005.

Dolcini 1992

Loretta Dolcini, Verrocchio’s sculpture; a Florentine itinerary, Florence, 1992.

Florence 1992

Legacy of the Magnificent, exhibition catalog edited by Paola Barocchi, Beatrice Paolozzi Strozzi and Marco Spallanzani, Florence, Museo Nazionale del Bargello, June 19-December 30, 1992, Florence, 1992.

Florence 2008

Florence and the Ancient Netherlands, exhibition catalog edited by Bert W. Meijer and Serena Padovani, Florence, Palazzo Pitti, June 20-October 26, 2008, Livorno, 2008.

Fulton 2006

Christopher B. Fulton, An Earthly Paradise: The Medici, their Collection and the Foundations of Modern Art, Florence, 2006.

Gamba 1904.

Carlo Gamba, “A Terracotta by Verrocchio at Careggi,” L’arte, vol. 7, 1904, pp. 59-61.

Gamba 1931/32

Carlo Gamba, Andrea del Verrocchio’s Resurrection at the Bargello, “Bollettino d’Arte,” vol. 25, 1931-32, pp. 193-198.

Lillie 1998

Amanda Lillie, “Chapels and Churches of the Medici Villas at the Time of Michelozzo,” in Michelozzo Sculptor and Architect (1396-1472), edited by Gabriele Morolli, Florence, 1998, pp. 89-98.

Passavant 1969

Günter Passavant, Verrocchio: Sculptures, Paintings, and Drawings. Complete Edition, London, 1969.

Planiscig 1941

Leo Planiscig, Andrea del Verrocchio, Vienna, 1941.

Pope-Hennessy 1971/85

John Pope-Hennessy, Italian Renaissance Sculpture, London, 1971,3rd ed., Oxford, 1985.

Schottmüller 1933

Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. Bildwerke des Kaiser-Friedrich-Museums. Die italienischen und spanischen Bildwerke der Renaissance und des Barocks, I, Frida Schottmüller (ed.), Die Bildwerke in Stein, Holz, Ton und Wachs. Zweite Auflage, Berlin, 1933.

Serros 1999

Richard D. Serros, The Verrocchio workshop: techniques, production and influences, Ph.D. diss., University of California, Santa Barbara, 1999.

Valentiner 1930

Wilhelm R. Valentiner, “Leonardo as Verrocchio’s Coworker,” Art Bulletin, vol. 12, no. 1, 1930, pp. 43-89.

Warburg 1932

Aby Warburg, Gesammelte Schriften, Leipzig-Berlin, 1932.

The author of this article: Vincenzo Sorrentino

Nato a Napoli nel 1990, si è laureato a Pisa in Storia dell’arte nel 2014 e si è addottorato a Firenze nel 2018, all’interno del programma “Pegaso” in cui sono consorziate le Università toscane. Ha svolto un internship di sei mesi nel dipartimento di scultura della National Gallery of Art di Washington D.C. e da gennaio 2019 è iscritto alla Scuola di Specializzazione in beni storico artistici dell’Università di Firenze.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.