“Over the past two decades, Sanyu has become one of the masters of modern Chinese art. His paintings, which once attracted collectors primarily in Taiwan, have now won over a wide range of collectors throughout Asia. However, unfortunately, interest in his paintings as a viable financial investment has grown out of all proportion to aesthetic appreciation, not to mention curiosity about the historical and social environment that provided the backdrop for his creativity. Although more museums and scholars are turning their attention to the much neglected but historically essential early 20th-century Western-style modern Chinese art, most focus on artists who returned to China from the West to share what they had learned or those who remained in the West where they achieved a certain level of success. Sanyu does not fall into any of these categories. Except that his works, after his passing, were sold at high prices at auction.” This is what can be read in the introduction to the catalog raisonné of Sanyu ’s (Chang Yu; Nanchong, 1895 - Paris, 1966) work, published in 2001 by the University of Washington Press, and the result of years of study and research by Rita Wong, a very relevant figure in the field of auctions and who at the same time can be considered one of Sanyu’s leading experts.

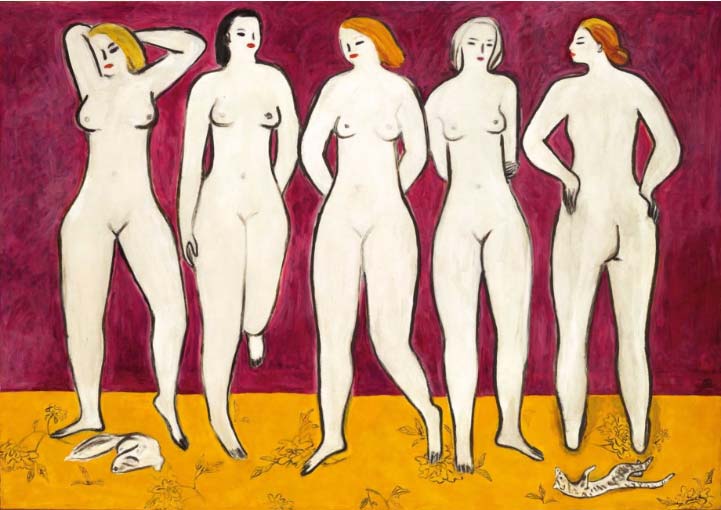

She is credited with the reconstruction of the work of the Chinese artist known as “the Oriental Matisse,” who has been so highly priced in recent years at Sotheby ’s and Christie’s auctions and sought especially by Chinese collectors: his works fetched exorbitant sums and his name came back to prominence in the 1980s and 1990s thanks in part to promotional work by a number of Taiwanese galleries such as Lin & Keng Gallery, Dimension Art Center and Tina Keng Gallery. In Hong Kong in 2019 Nu (1965), Sanyu’s last nude painting, was auctioned for US$25.24 million at Sotheby’s, while Cinq Nus (1950-1959) was sold for $38.72 million at Christie’s, and again in 2020 Fleurs dans un pot bleu et blanc (1950) for $25.5 million, and in 2021 Nu avec un pékinois for $13.5 million, also at Sotheby’s.

Before discussing the artist’s work, however, it is worth delving into some of his biographical coordinates. Sanyu (or Chang Yu) was born in Nanchong, Sichuan Province, in 1895 to a wealthy family that owned one of the largest silk factories run by his brother Chang Junmin, thirty-seven years older. From a young age Sanyu revealed a natural inclination for art, cultivated through calligraphy lessons taught by master Zhao Xi and drawing lessons assisted by his father, a skilled painter. In 1921, after a period in Japan and Shanghai, while China was undergoing great hardship under Beiyang’s “warlords,” Sanyu, just 19 years old, thanks to a government-sponsored work-study program organized by Cai Yuanpei, rector of Peking University, was among the first Chinese artists to travel to France, to Paris. There he met other art students, such as Xu Beihong (who would become one of the landmarks of academicism in China) and the latter’s wife, Jiang Biwei, with whom he befriended and decided to move to the cheaper Berlin, where, together with other creative people, he founded a culinary club, neglecting his artistic activity. In fact, only two works painted in brush and ink, in the traditional style, remain from this period: Pivoines and Paysage avec saules.

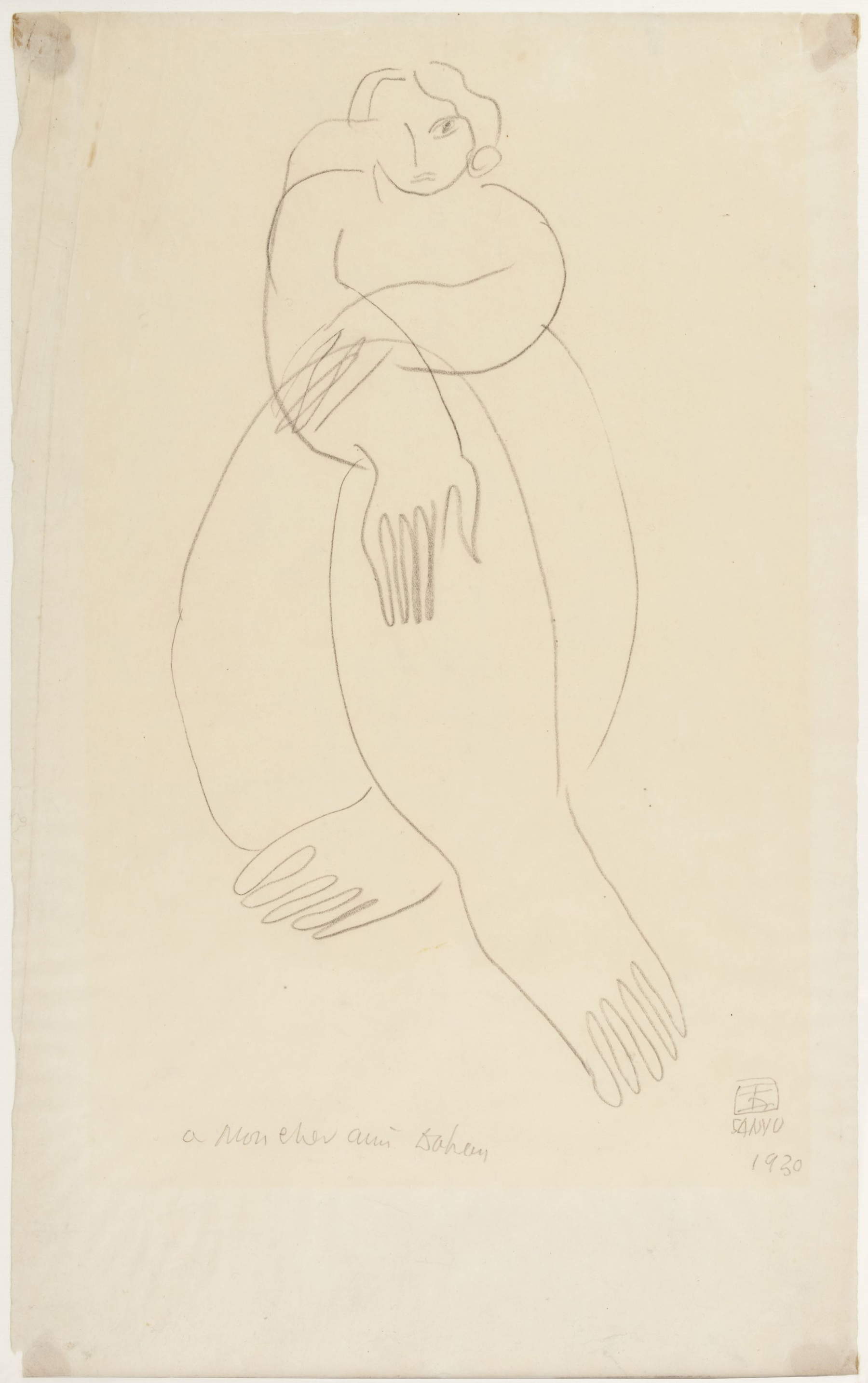

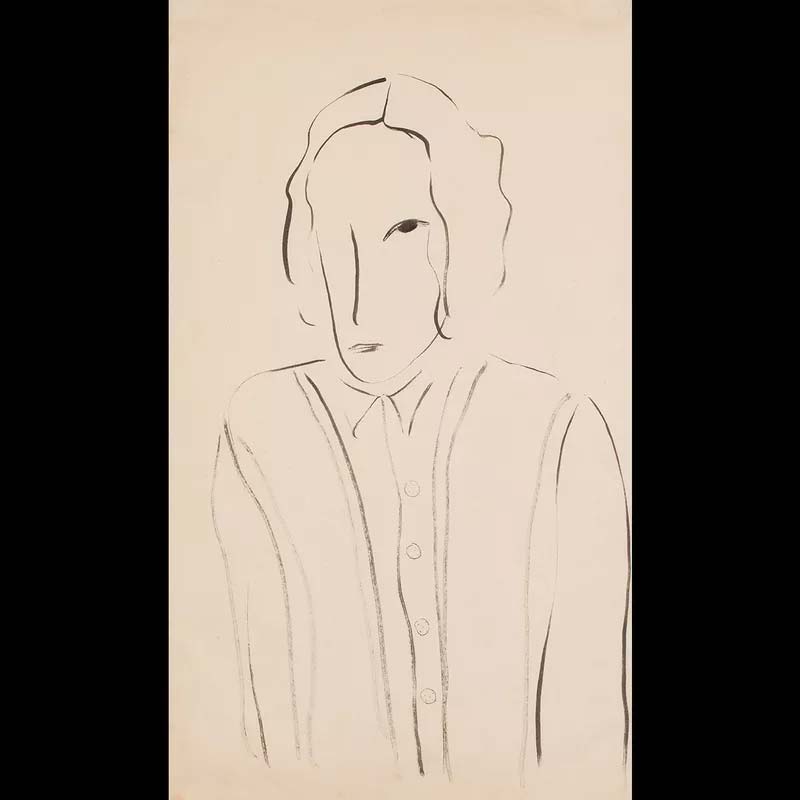

After two years in the German capital, Sanyu decided to return to Paris to attend theAcadémie de la Grande Chaumière, less traditional than the more renowned École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux Arts: in a free and experimental climate completely foreign to the closed reality from which he came, the young man was able to try his hand at Western painting techniques and nude studies through classes with life-size models. There are about 2,000 of these drawings, most of them executed with Chinese ink and brush. During classroom lessons, he met what was to become his wife, Marcelle Charlotte Guyot de la Hardrouyère, a young woman in her twenties who was fascinated by his talent.

The Académie de la Grande Chaumière was located in a nerve center of life and culture, right in the heart of Montparnasse, close to numerous cafes and gathering places for artists and intellectuals such as La Coupole, Le Dôme, and La Closerie des Lilas. Chagall, Zadkine, Soutine, Foujita, to name but a few, and, shortly before his untimely death, Amedeo Modigliani also lived here. This environment was a continuous source of inspiration for the young Sanyu who, fascinated by scenes of daily life and people of different and therefore exotic ethnicities, spent hours drawing on paper placemats, heedless of daily survival, strong in the knowledge that his brother was ready to provide for him. In this context he met Alberto Giacometti and had his portrait drawn by Pablo Picasso, of whom he was a great admirer.

Sanyu

Sanyu

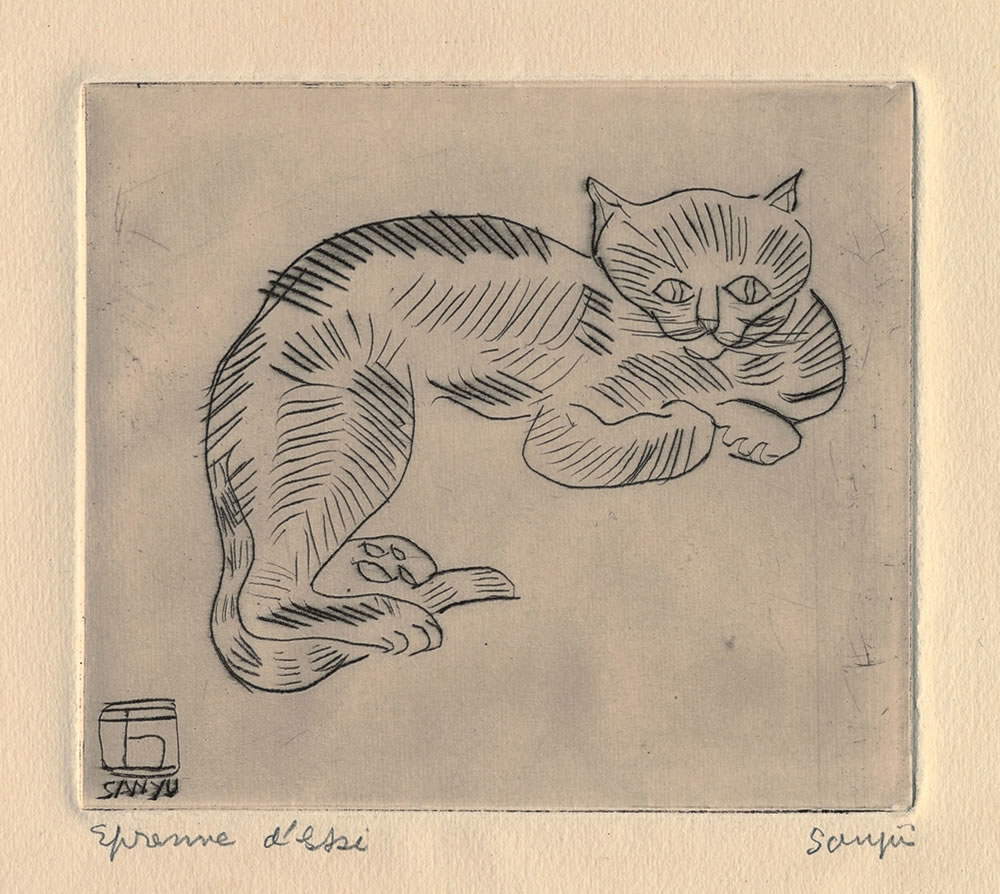

His meeting with Henri-Pierre Roché, the well-known author of Jules et Jime and Les deux anglaises et le continent, as well as an active art collector and dealer, adept at discovering talent, dates back to 1929. He had introduced Picasso to Leo and Gertrude Stein and was friends with Georges Braque, Marcel Duchamp, and Constantin Brancusi. Although Sanyu in the past had always been reticent about dealing with art dealers, so much so that he even preferred to give his works as gifts, in order to relieve himself of the material worries he was experiencing at the time, as his brother’s aid was becoming irregular, he agreed to work with Roché. In 1931 the patron bought him 111 paintings and about 600 drawings and encouraged him to experiment with printing, which was less expensive and could reach a wider audience. Sanyu first began experimenting with drypoint with results of small, velvety and refined works, and then withlinoleum etching, anticipating Picasso and Matisse by a few years, a procedure that allowed him to work on large format. Also in 1929 he began to paint in oil, a technique that accompanied him constantly throughout the 1930s as evidenced by the works exhibited at the Salon des Tuileries where he managed to participate as the only Chinese artist. Between 1930 and 1932, Sanyu experienced a dark period marked by the death of his brother resulting in a lack of financial support, his divorce from his wife who accused him of infidelity as well as his breakup with Roché. The latter, in spite of everything, never parted with his collection: the entire lot in 1966 was auctioned off by Roché’s widow and purchased entirely by Claude Riedel.

However, these were also the years in which he formed a deep friendship with the Dutch composer Johan Franco, a descendant of the Van Gogh family, who not only supported and promoted his work to wealthy relatives as well, but also organized several exhibitions in Holland. He was so bound to the artist that he had it written in his will that in the three months following his death he would set aside an annuity of 500 francs for him. Although he had taken part in a number of exhibitions at the Salon d’Automne, the Salon des Indépendants and the Salon des Tuileries and had on his side the esteem of several fellow artists who showed great admiration for him, recognizing him as a leading precursor ofmodern Chinese art (Pang Xunqin invited him to join the Storm Society,an art group born in Shanghai, and Xu Beihong included him in a major group show at the National Museum of Foreign and Contemporary Art-Jeau de Paume de Tuileries), his art was struggling to take off.

So Sanyu decided to reinvent himself by devising a new sport: ping-tennis, a hybrid of the two disciplines in which one plays on a small squash court with a net, using badminton-like rackets and a large ping-pong ball. Enthusiastic about his invention, he traveled to Berlin to the Olympics in 1936 to meet tennis champion Gottfried von Cramm in order to engage him to popularize the new sport, unfortunately with poor results.

Unable to procure the coveted success, in the late 1930s and early 1940s, with World War II raging, completely bereft of finances, so much so that he was forced to make sculptures with shoddy materials such as plaster and paint, Sanyu left for New York, resolved to promote his sport and join tennis player Von Camm who had meanwhile moved to the United States after marrying a wealthy American heiress and perhaps get support, however in vain. In the meantime, however, fate would have it that the famous photographer Robert Frank was interested in an exchange of studies: he would fly to Paris and Sanyu would occupy his space in New York. By a series of coincidences Frank did not leave; the two artists thus found themselves sharing a studio. They became such great friends that when Sanyu decided to return to Paris in 1950, he left him all his works to compensate him for his expenses (in 1997 Frank would sell them and use the proceeds to establish the Sanyu Scholarship Fund at Yale University to help Chinese art students).

These were the years when the artist had to fall back on carpentry and restaurant jobs to survive. In 1963 he received an invitation from his compatriot, Taiwan’s Minister of Education Huang Jilu, to teach at the university and to hold a solo exhibition in Taipei. Sanyu sent 42 works determined to join them later and, with the advance, apparently undertook a trip to Egypt. For bureaucratic reasons, however, he then failed to leave for China but was stranded in Paris, where he died shortly thereafter in his studio from a gas leak. He was found lying on his bed with a book on his chest and an application for French citizenship filled out nearby. Family-less, completely destitute, he was buried in an anonymous grave at the expense of a French-Chinese community service association. The paintings were taken over by the National History Museum in Taiwan, a building constructed in the Ming Dynasty style overlooking the Botanical Garden, the main area of which later was designated to house them. The original corpus was later augmented with 10 more works: two oil paintings had been brought to the museum in 1980, in 1986 cultural attaché Kuo You-shou donated five more works, and three sketches were purchased in 2011. The museum has held as many as six retrospectives of the artist’s work: in 1978, 1984, 1990, 1995, 2001, and 2017.

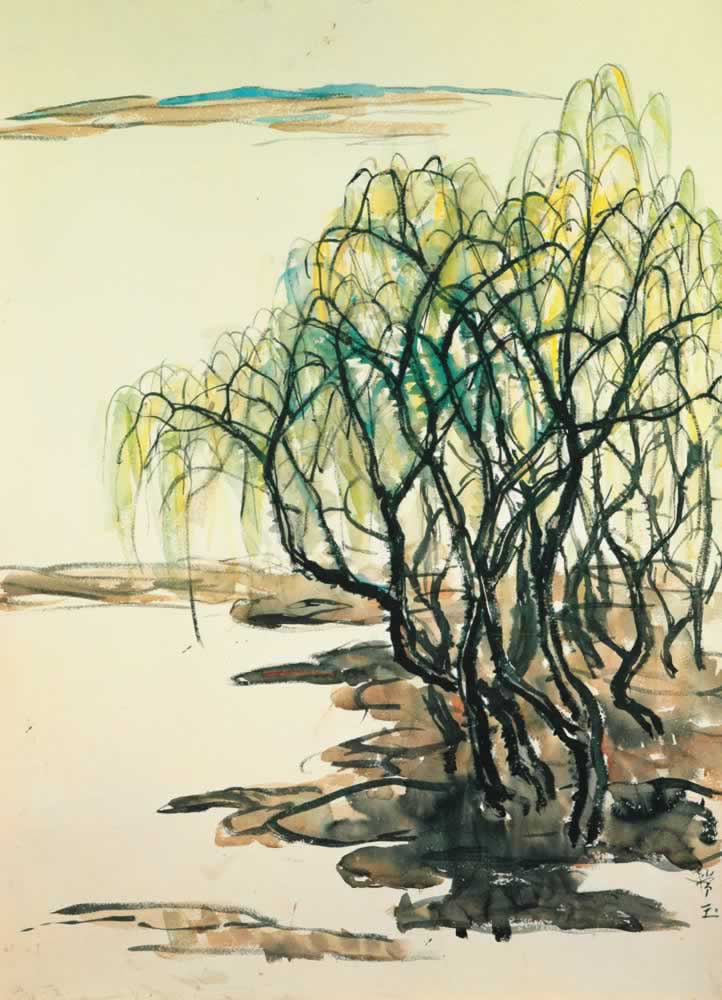

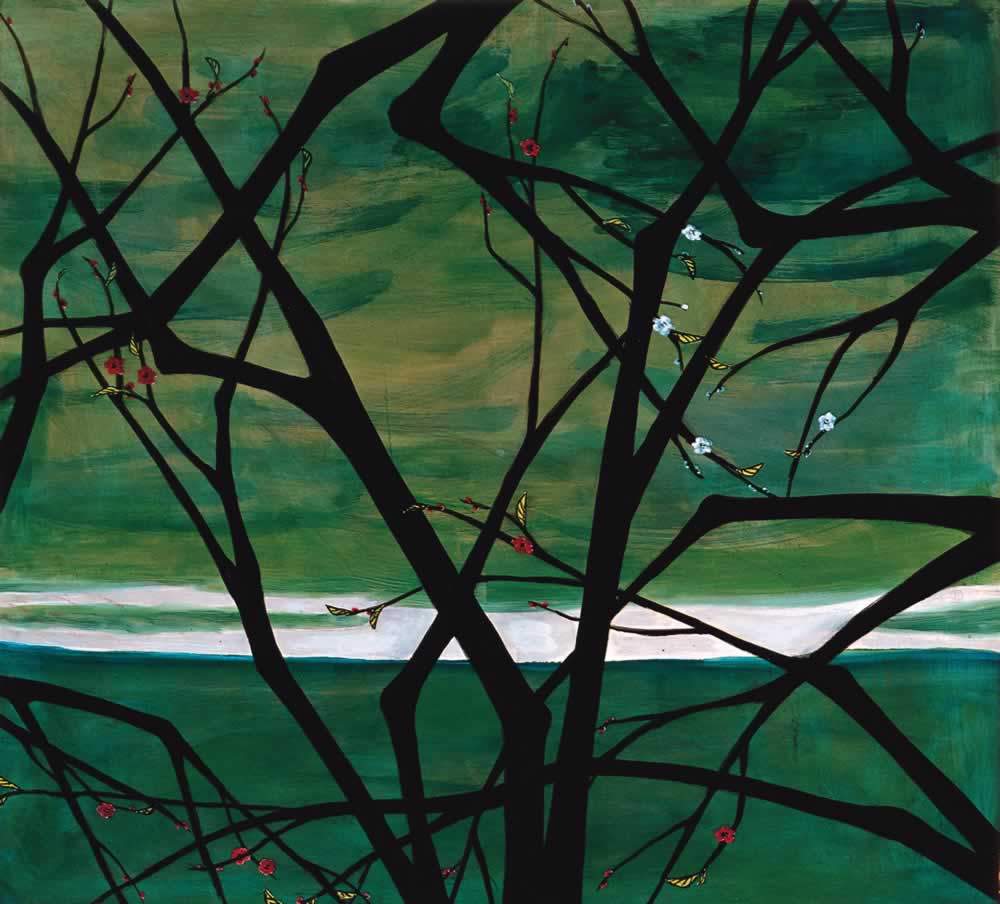

Sanyu was not what one might call a prolific artist: in total he produced about three hundred oil paintings, on canvas or masonite, less than three hundred watercolors, about two thousand sketches, and a small number of sculptures and prints. In his works the calligraphic virtuosity typical of the Orient comes to amalgamate with modernist lines giving rise to exuberant and sinuous compositions with chromaticisms in the odor of Fauvism. Figures, female nudes “with the thighs of the universe”(as the well-known poet Xu Zhimo called them in a humorous tone), landscapes, animals, still lifes: these are the artist’s favorite themes.

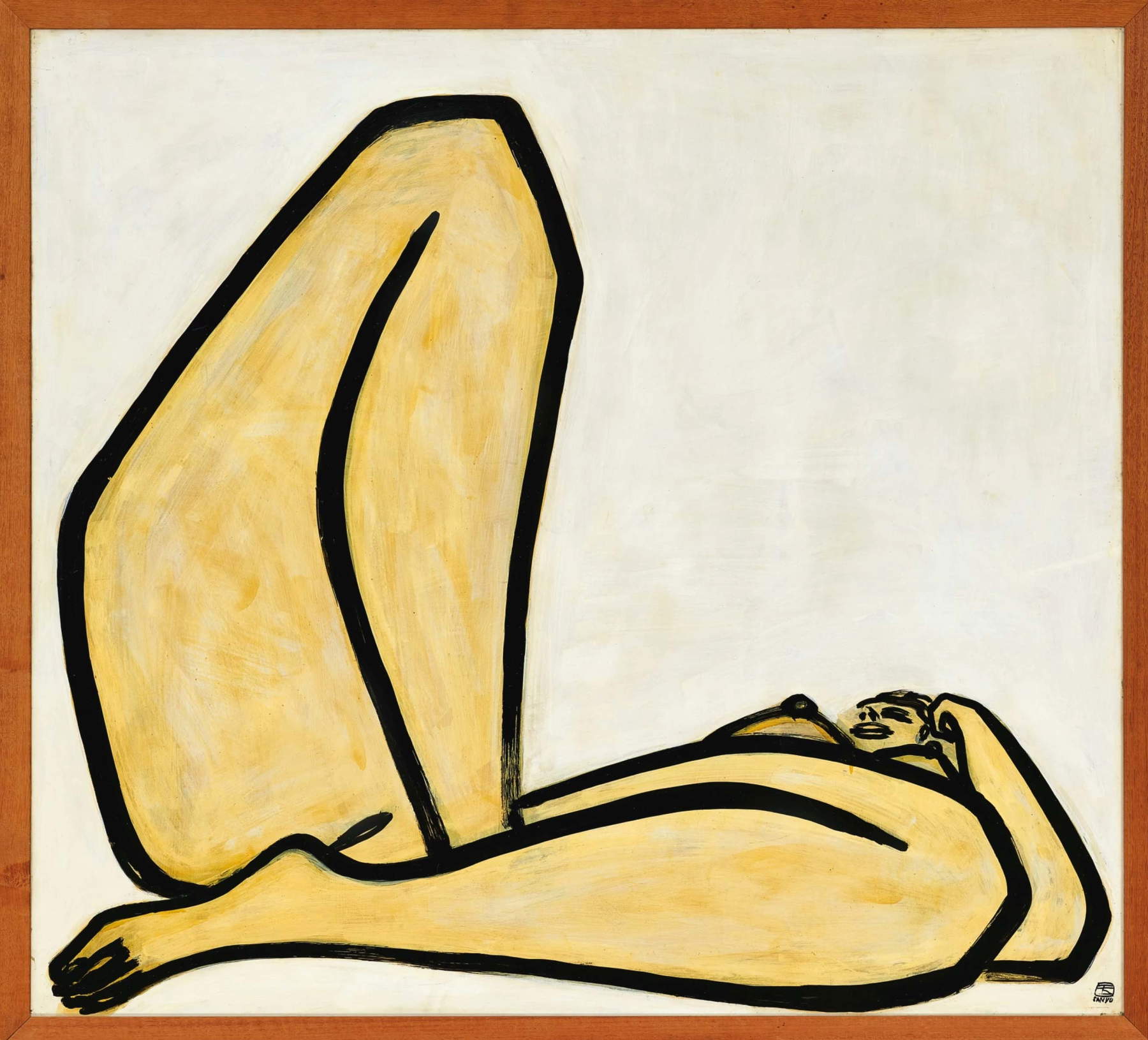

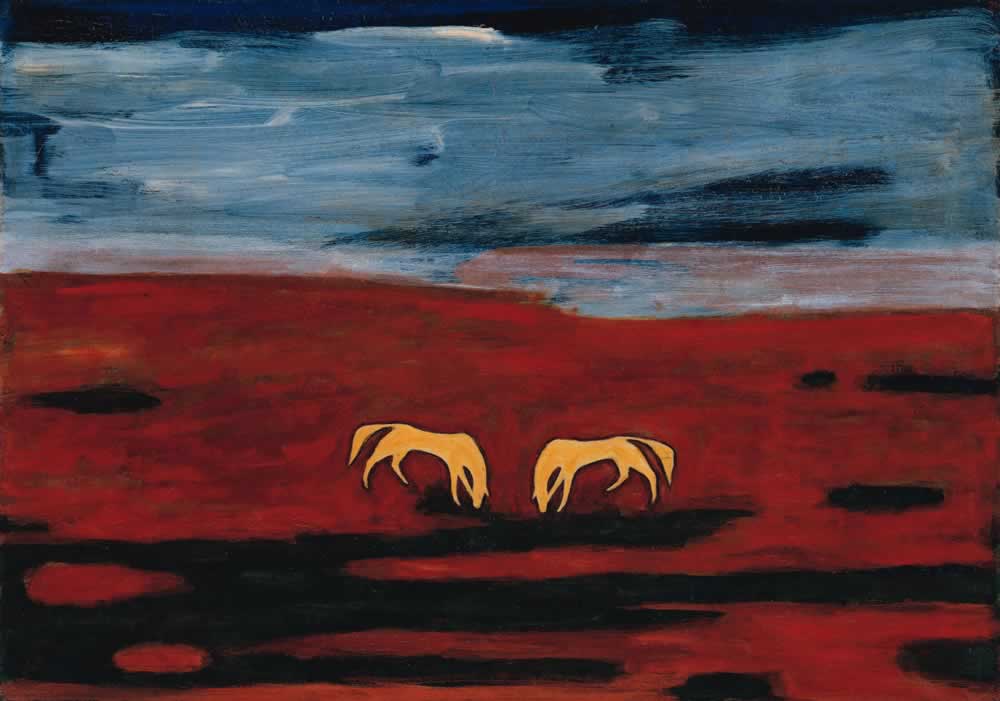

The nudes, a privileged subject that recurs throughout Sanyu’s career, are minimalist and strongly imbued with eroticism; the female figures standing, sitting, lying down, sometimes depicted in contorted poses that give rise to geometrisms, in spaces without perspective, closed lips, a barely noticeable nose, are often depicted with only one eye (a detail reminiscent of the portraits of the famous Kiki) and with an exaggeration of the lower part. Compared with drawings where a single subject is immortalized, in oil paintings we often find groups of women: from the early nudes with complexions reminiscent of Tang dynasty courtesans and rounded, voluptuous forms belonging to the so-called “pink period,” we move on to more tapered female physiognomies with ochre skins traceable to the period of the same name. Animals, another constant and beloved presence, whether exotic or companionable (cats and Pekingese portrayed in domestic settings while playing, resting on chairs or drinking milk), always convey states of mind assimilated to those felt by humans: a leopard absorbed in his thoughts, pairs of animals looking at each other with tenderness.

Over the years, the artist began to place solitary animals in boundless landscapes, exemplifying the feeling of loneliness he felt in old age. In the still lives (to which the Museo Morandi in Bologna in 2019 dedicated a refined and original exhibition, curated by Zeng Fanzhi, in which Sanyu’s works were related to works by Cézanne and Morandi),fruit and flower compositions stand out, harking back to the tradition of Chinese literati painting: peonies, chrysanthemums, plums, lotus blossoms and bamboo but also pomegranates and olive trees, symbols of prosperity and good luck.

Tina Keng, one of the foremost experts on Sanyu’s work, in a 2009 interview, summarized the artist’s characteristics that reveal the artist’s authenticity as follows, “Sanyu has a solid foundation in Chinese calligraphy and epigraphy so his strokes of spatial relationships, lines and brushstrokes are never haphazard [....] as an elegant and minimalist person his works carry the same clarity and rigor in their texture and composition [...] his detached and unflappable nature is reflected in his work which is never vulgar.”

In the 1960s, near the end of his career, Sanyu declared, “after a lifetime devoted to painting, I finally know how to paint.” He, capable of modest statements, in addition to being a pioneer in that he helped create a new aesthetic, was also able to leave an indelible mark on contemporary Chinese generations of young and already established artists such as Shafei Xia.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.