There was a time when the ancient people ofEgypt began to reserve a deep veneration for animals, considering them to be incarnations on earth of deities. The crocodile, for example, was seen as the embodiment of the powerful god Sobek, a symbol of power and fertility. The ibis, on the other hand, represented Thoth, the deity of writing and wisdom, embodying knowledge and intellect. The hawk, a symbol both on earth and in the sky, was associated with the god Horus, deity of the sky and protector of the kingdom. However, among all the deities worshipped, one creature emerged that occupied an important place in the landscape of the Egyptian pantheon: the cat, which, in addition to being a skilled hunter, was considered sacred and represented the silent guardian of the two worlds, the earthly and the afterlife. The cat embodied multiple meanings and symbols in Egyptian culture: it was associated with protection, fertility and prosperity, as well as the ability to deal with the forces of evil and chaos. It embodied a fusion between what was their sacred and protective nature and what was instead their domestic companionship.

The cat also played a distinct role in everyday life: Egypt was a well-organized agrarian society, which involved the storage of large quantities of grain. This attracted large numbers of unwanted ’pests’ such as rodents and small birds, and the same waste thrown into and around settlements attracted additional opportunistic animals. It is therefore likely that wild cats approached villages to hunt these critters. Snakes were also attracted to the same profiteering animals, especially when they were seeking higher ground during floods: however, they were feared because of their potential danger to humans and livestock. The presence of cats in villages and farming communities therefore led to a significant reduction in rodent populations that damaged crops, thus contributing to the food security of the population. At the same time, their ability to keep snakes away made them even more valuable and respected. As a result, residents encouraged their stay in the vicinity of homes by leaving leftover food to attract them and convince them to settle. In addition to this, according to a New Kingdom papyrus on the interpretation of dreams, seeing a big cat was considered auspicious, as the appearance of felines near fields was considered to herald a great harvest.

The presence of cats in Egyptian homes was also a symbol of prosperity and wealth. Wealthy families often kept cats as pets, and depictions of cats in artwork, amulets, and jewelry were common. Their veneration was also reflected in the arts and funeral rituals: cats were often depicted in bronze statues, amulets, now preserved in various museums around the world, and some received ceremonial treatment in burial. The deep admiration for felines, evident in archaeological remains such as the cat mummies housed in the Egyptian Museum in Turin and in ancient texts, gives a glimpse into the spiritual and daily life of Egypt.

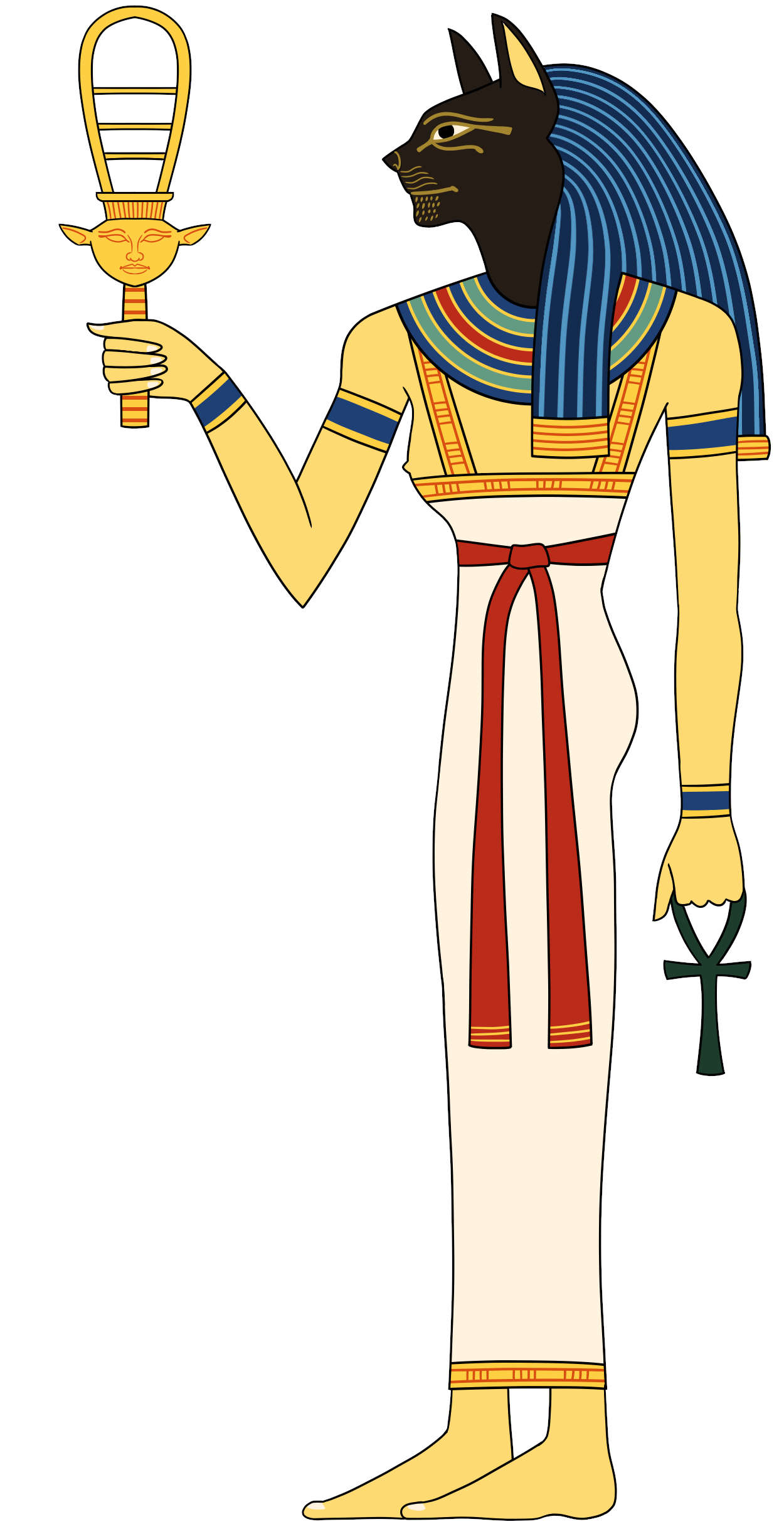

Religiously, however, as with every other manifestation of Egyptian zooform deities on earth, the cat was the embodiment of the goddess Bastet, depicted as a woman with a cat’s head. Bastet was the goddess of home, warmth of the sun, fertility and protection and was considered the protector of pregnant women and children. Over time her name underwent several evolutions: originally it was B’sst, then it became Ubaste, later Bast and finally Bastet. The exact meaning of the name is not known or at least not universally agreed upon. Egyptologist Geraldine Pinch suggests, however, that her name probably means “She of the Jar of Ointment,” since Bastet was associated with protection and protective ointments. In the city of Bubasti (today’s Tell Basta), her cult was particularly heartfelt and the deity was worshipped with deep devotion. Although cat worship was already present at the beginning of the New Kingdom (about 1550 B.C.), it gained greater prominence in 943 B.C. - 922 BC. At that time, Bubasti (originally Par-Bastet, or “house of Bastet,” present-day Zagazig) became an important center of Bastet worship, located in the eastern part of the Nile delta, and Bastet became a popular deity, patron of fertility and motherhood, associated with the positive aspects of the sun’s rays. The concept came into contrast with the different nature of her sister Sekhmet, who in contrast to the figure of Bastet, embodied the destructive power of solar heat and rebirth, depicted with a female body and the head of a lioness.

Unlike the figure of Bastet, Sekhmet’s name reinforces her indomitable nature: the Mighty or the Mighty. Many of her epithets are also: Lady of Heaven, Lady of the Two Lands, Lady of the Gods, and the Great, and as many of her titles allude to her nature as the “Lady of Many Faces,”“Lady of Flame,” and the “Lady of Heat.” In her benevolent aspect, Sekhmet is the “Good Eye that gives Life to the Two Lands” and the “Lady of Bread and Offerings.” However, some of her names instead reflect her deadly side; she is known as the “Lady of Darkness” and “She Who Brings Death.” Sekhmet’s various powers have generated mixed feelings of fear and horror on the one hand, and awe and hope on the other. At Edfu, an inscription refers to her as the “Lady of all manifestations of Sekhmet,” highlighting the complexity and multidimensionality of her divine character. Sekhmet is a purely solar and lioness goddess, and her two main roles reflect her ambivalent nature: she is both bringer of war and disease and protector and healer. She is also “She who presides over the desert,” representing the drying influence of the sun and the dangerous chaos of desert regions. The hot desert winds were said to be the “breath of Sekhmet.” There is probably no Egyptian statue more famous or widespread than those of Sekhmet commissioned by Amenhotep III (18th Dynasty) for his funerary temple at Karnak. The pharaoh had more than 700 statues of the goddess carved, now found in various museums around the world, such as the collection at the Louvre Museum. The statues, made of granodiorite, are about two meters tall and weigh two tons each, and their color varies from deep black to brownish-red. Black symbolized the fertile earth, while colors such as red and gold referred to the sun.

Both deities were identified as the Eye of Ra: if Bastet represented the mild and protective side, Sekhmet depicted the violent one. Their dualism reflected the Egyptian people’s deep fascination with opposites, a constant theme in their religion dating back to the predynastic period. In the Middle Kingdom, on the other hand, the male cat had a crucial function both as a representation of the sun and as its defender: during the night, he was to protect the star from the attacks of the serpent-demon Apopi. This was the Great Cat of Heliopolis, a transformation of the sun-god Ra into a feline. Often depicted intent on guarding a persea tree, the Tree of Eternal Life and Knowledge, the Great Cat confronted Apopi by crushing his head with one paw and stabbing him with the other. The scene is frequently depicted in funeral wall paintings from the Book of the Dead (Chapter XVII). The male Great Cat is depicted as a feline with reddish fur, often spotted and bristly on his back, with a long tail, sometimes with a protruding tongue and hare-like ears. Sitting on his hind legs, he guarded the sacred tree of Heliopolis, the Ished tree, on whose leaves Thoth wrote the coronation names of Egypt’s rulers. The tree, by dividing, allowed the sun to rise. What is more, the cat was associated with Ra for his ability to kill snakes; an ability that made him especially revered, independent of any other solar attribute. Unlike lions in fact, cats were known for this specific ability. A significant example of the union of the solar deity and the feline is a Late Period statue, 672 to 525 BCE, which depicts a cat with the face and chest of a hawk, a combination that may represent the dual aspects of Ra.

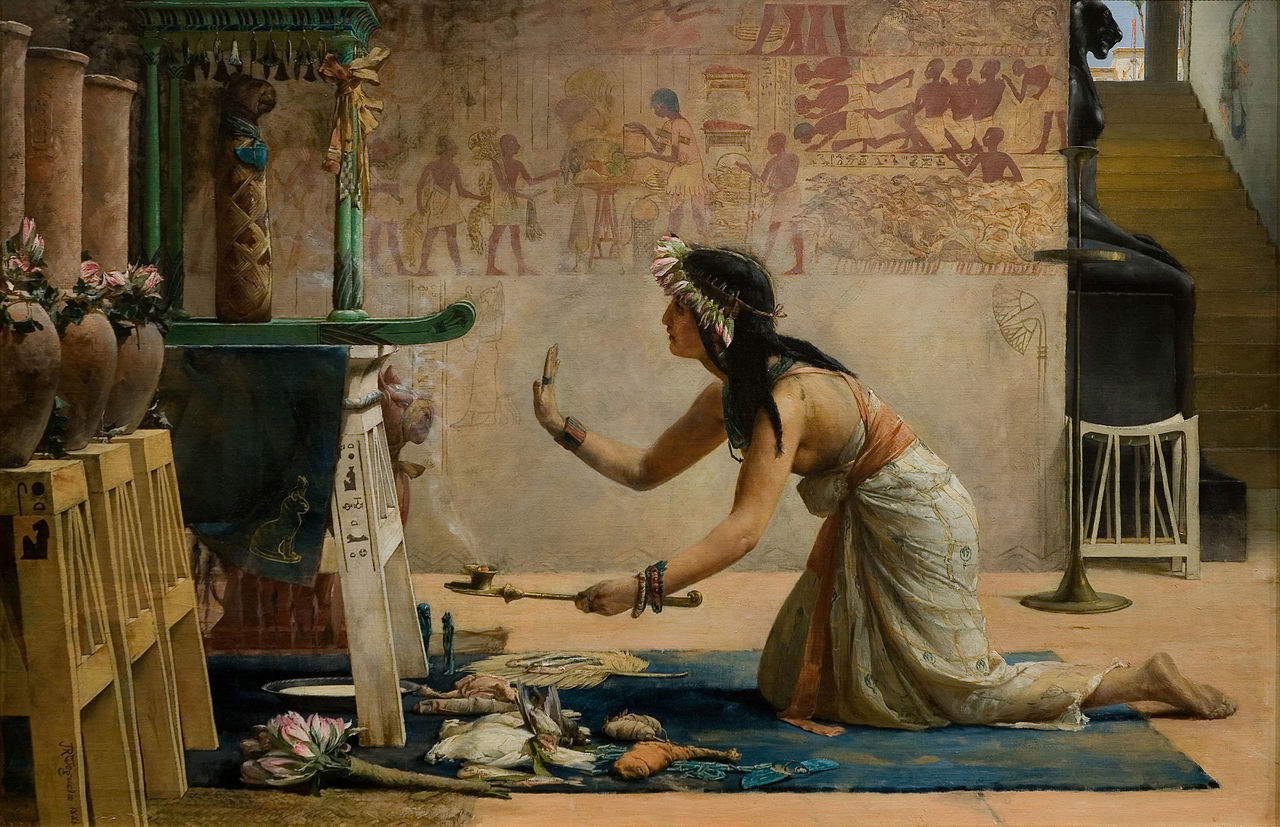

Away from ancient Egypt and into modern times, interest in ancient Egypt spread widely in the Western world, especially after Napoleon ’s expedition to Egypt in 1798. The phenomenon influenced several fields, including art, literature, design and more, taking the name Egyptology. John Weguelin (South Stoke, 1849 - Hastings, 1927), an English painter, was influenced and fascinated by the rich Egyptian material that was being excavated and housed in museum repositories, such as the British Museum, for example. His ability to depict scenes that seemed to bring ancient history to life captured the imagination of Victorians who were fascinated by ancient Egypt. Most notably, in the 1886 painting entitled The Obsequies of an Egyptian Cat, Weguelin depicted a funeral ceremony for a mummified cat.

In the work, a priestess is bowed before an altar where a cat mummy is placed, offering food and milk to the feline spirit, made worthy of honor. The altar is carefully ornate, decorated with frescoes and along with urns of fresh flowers and lotus blossoms, flowers symbolic of ancient Egypt. The priestess, with her eyes turned skyward, spreads the smoke of incense toward the altar, invoking the feline deities to bless the animal on its journey to the afterlife. In the background, on the other hand, an imposing statue of Sekhmet, made notable for her posture and barely noticeable headdresses, guards the entrance to the tomb. In the painting, an atmosphere of devotion and sacredness emerges, where ancient burial ritual merges with spirituality and veneration for the cat considered a valuable companion during life and an indispensable spirit in the afterlife.

Two significant examples of paintings devoted to Egyptology and featuring feline depictions are also the paintings of English artist Edwin Long (Somerset, 1829 - Hampstead, 1891). In The Gods and Their Makers of 1878, Long captures the essence of Ancient Egypt in the imagination in late 19th-century Europe: an exotic image that found its continuation especially in film and popular culture. In a setting filled with sculptures dedicated to the deities of the Egyptian pantheon, the viewer’s gaze immediately falls on the figure of a black servant girl holding a white cat in her arms as the artist models its forms through a block of stone or perhaps clay. The people in the scene, probably students or apprentices, hold small ornaments in the process of creation, demonstrating the link between art, religion, and everyday life. In Sacred to Pasht of 1886, Long instead depicts a scene within a large, finely decorated room. Two women worship several cats by pouring them a large amount of milk into a golden bowl while in the distance, three female figures, probably priestesses, pray to and invoke Sekhmet’s benevolence through her statue. The same benevolence is reserved for the cats in the foreground, considered manifestations of the deity on earth. Long’s works, like Weguelin’s, therefore reflect the period’s fascination with ancient Egypt, its religion, and the importance attached to felines as symbols and animals of divine protection and devotion.

The author of this article: Noemi Capoccia

Originaria di Lecce, classe 1995, ha conseguito la laurea presso l'Accademia di Belle Arti di Carrara nel 2021. Le sue passioni sono l'arte antica e l'archeologia. Dal 2024 lavora in Finestre sull'Arte.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.