If Genoa is one of the most fascinating and art-rich cities not only in Italy but in the whole world, it owes this in large part to a complex of buildings that have a unique history and that were embedded in a system that has no equal elsewhere: these are the Palazzi dei Rolli. On these pages we have talked about some of these palaces, but we have never devoted an article giving an overview of the history of this unique complex of buildings, which, moreover, in 2006 was awarded UNESCO World Heritage status precisely because the Palazzi dei Rolli of Genoa represent, as we also read on the UNESCO website, “the first example in Europe of an urban development project promoted by a public authority within a unified framework and associated with a particular system of public housing within private residences.” The history of the Rolli began in 1576.

Genoa then was, as it still is today, a busy port city at the center of much commercial and financial traffic, but it had two problems: first, the Republic of Genoa did not have an official seat that could decorously accommodate distinguished guests from abroad visiting the city. And their numbers, given the greater political and economic clout the Republic had acquired during the 16th century, were steadily increasing. Second, there were no decent hotels; there were only small inns, mostly populating the city’s run-down neighborhoods. Therefore, in order to provide the most comfortable and worthy accommodations possible for ambassadors, cardinals, legates, princes, and sovereigns visiting Genoa, on November 8, 1576, the Senate of the Republic passed a decree establishing a list of houses obligated to public lodgings: a series of buildings, the most sumptuous in the city belonging to the most prominent families of Genoa, which were to take charge of providing lodging for the illustrious guests of the Republic should the need arise. The first list (or"rollo," literally"role," a term that denoted precisely the list of buildings) contained fifty-two houses, which would increase in number with subsequent rolli. In all, in fact, five rolli were issued: in addition to that of 1576, we have one from 1588 (111 houses), one from 1599 (120 houses), one from 1614 (88 houses), and one from 1664 (96 houses). But what were some of the guests who stayed at the rolli palaces? We can count, for example, the Duke of Joyeuse, brother-in-law of Henry III of France, who in 1583 stayed at the Tobia Pallavicino Palace, which six years later also hosted Pietro de’ Medici, brother of the Grand Duke of Tuscany, Francis I. Again, in 1592 it was the turn of Vincenzo I Gonzaga, duke of Mantua, who was hosted in what is now known as Palazzo Pallavicini-Cambiaso, while in 1599 Francesco Grimaldi’s palace, better known as Palazzo della Meridiana, welcomed the queen consort of Spain, Margaret of Hapsburg, wife of Philip III.

|

| The facade of the Tobia Pallavicino Palace |

|

| The facade of the Palazzo della Meridiana |

There were several categories of buildings registered on the rolls, and usually it was the wealth and magnificence of the palace that determined whether it belonged to one or the other category. The categories, identified by the"bussoli,“ or compasses that were used to draw, by public drawing of lots, the name of the building that was to welcome the guest visiting Genoa, also indicated what kind of personality a palace could accommodate. For example, in the rollo of 1599, there were three bussoli, and they made a distinction between first-rate palaces, which could accommodate cardinals, ”grand princes“ i.e., independent foreign rulers, the viceroys of Naples and Sicily, and the governors of Milan; second-rate palaces intended for feudal lords; and third-rate palaces, which could accommodate ambassadors and princes of lower rank than those who could be accommodated in first- and second-rate palaces. Also in the rollo of 1599, however, freedom was left to the Senate of the Republic to decide which palace was suitable ”for lodging popes, emperors, kings and their sons and brothers and nephews": for the most illustrious heads of state, therefore, the system of drawing lots did not apply, but the seat that would accommodate them was determined by the Senate. Genoa had thus created what historian Ennio Poleggi, the leading scholar of the rolli system, called a"republican palace," a kind of diffuse, sumptuous but also contradictory grand court, because it was already seen at the time as the most obvious symptom of an unsustainable confusion of roles between public and private, and also because it was an expression of the all-Genoese attempt to offer guests an image of splendor similar to that of the absolute monarchies of the seventeenth century behind which, however, lay the divisions of an oligarchic republic in the hands of families belonging to opposing factions.

|

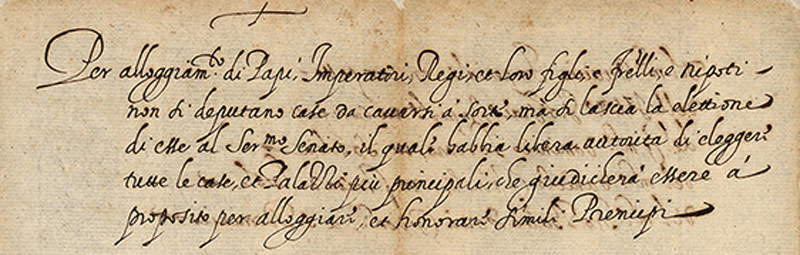

| Beginning of the roll of 1599, preserved in the Genoa State Archives. |

And these oppositions also affected the rollo system itself: today we have been handed down the glowing image of Genoese families who did everything they could to make their palaces magnificent in order to win the most prestigious guests, giving luster to the republic, but the reality that emerges from the documents tells us a different story. In fact, if on the one hand there were families who were well disposed to receive foreign guests and thus sought to elevate the magnificence of their residences (these were mostly families of bankers or at any rate of great merchants who saw the possibility of providing lodging for distinguished guests as an opportunity to increase their wealth and power), on the other hand, there were families who saw the task as a terrible nuisance as well as, in a city of often distrustful and unwelcoming people (an image that Ligurians have dragged with them to this day), as an intolerable invasion of the Republic into the private lives of its citizens. It should also be added that the Republic bore part of the expenses, those destined for the most important guests, and for the rest the burden was on the owners of the palaces: given also the proverbial propensity of the Genoese to save money, one can easily understand how many hoped that their name would not come out in the draw. A number of requests for exemption from the rolli are preserved in the Genoese archives, and we have also received direct testimony from citizens who were ill-disposed toward the obligation to accommodate foreign guests, often entrusted to so-called chalice tickets, anonymous letters that were issued in a hole, placed on one of the walls of the Ducal Palace, which collected them, precisely, in a chalice from which they were then drawn and read. Among the proudest opponents of the practice were several members of the Spinola family, who had always been lovers of thrift and sobriety: in 1620, Andrea Spinola (who was later doge) wrote in his Political and Philosophical Dictionary that “if a law were made here which would prohibit public lodgings, all the lords and ministers of princes would depart from here satisfied and content,” and fifty years later one of his nephews, Giovanni Francesco, lamented the waste of resources for a practice that might even have made sense when the Republic was going through periods of greater splendor, comparing the Palazzi dei Rolli, in a time of crisis, to the “bodies of great vessels pulled to seco on the sand.”

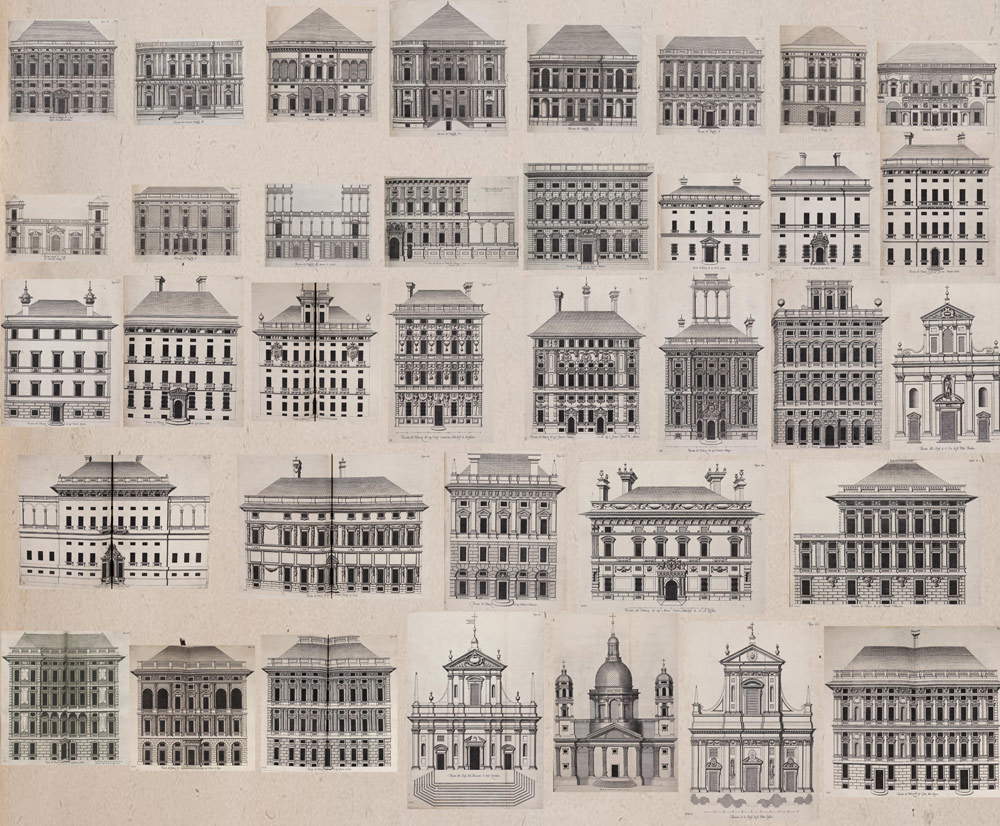

Despite internal divisions, in the eyes of the guests and distinguished travelers who happened to stay in Genoa, the Palazzi dei Rolli must have appeared as the most manifest symbol of the city’s splendor: we have pages upon pages magnifying the beauty of the buildings of the Genoese lords. One of the first guests of the Palazzi dei Rolli, Cardinal Giovanni Battista Agucchi (beautifully eternalized in a famous portrait by Domenichino) wrote in 1601 that “in few other places in Italy could equal magnificence be shown since in very few are to be found the gold, silver, jewels and draperies and rich furnishings that are seen here, beyond li palazzi et habitationi regie that have no paro elsewhere.” A century later, in 1739, the French philosopher Charles de Brosses compared the beauty of the Genoese palaces to that of the palaces in Paris, and a compatriot of his, the man of letters Charles Dupaty, some forty years later was almost shocked by the sumptuousness of the city’s buildings. One of the travelers who was most impressed by the palaces of the rolli, however, was the great Pieter Paul Rubens, who stayed several times in the city and was so enthusiastic about what he had seen in Genoa that he compiled a book, Palaces of Genoa, printed in 1622 and later republished in a second edition in 1652, which constitutes the first collection in which the city’s principal palaces are described in detail, complete with precise reproductions of the architecture: the book constitutes an indispensable reference point for studying the palaces of the rolli.

|

| Illustrations of the buildings from Rubens’ Palazzi di Genova |

Palacesof Genoa is also one of the earliest texts that handed down a perception of Genoa quite different from the one its inhabitants must have had. It is probably also thanks to the testimonies of travelers who passed through the city that it has recently come to propose to the public an image of the palaces of the rolli as an element of a conscious civic identity, which, however, as a recent study by historian Clara Altavista also points out, probably does not correspond to the feeling of the Genoese of the seventeenth-eighteenth century and is rather configured as a historiographical construction through which the city was given “that court it never possessed in which to recognize itself, but of which perhaps the Genoese had never felt the lack, except precisely on the occasion of official state visits.” The operation could, however, be partly justified precisely by the way Genoa had to appear in the eyes of its visitors, and there is no doubt that at least the Genoese of today take particular pride in their palaces to the point of dedicating to them the days known as Rolli Days, which certainly remain one of the most interesting cultural events held in our country.

When did the custom of receiving distinguished guests in the palaces of the rolli end? We do not know for sure, there is no definite date, but we do know that the custom lasted at least until the early eighteenth century. Most of the buildings originally listed in the Senate lists survive today with a wide variety of destinations. Tobia Pallavicino’s palace became the seat of the Chamber of Commerce. That of Angelo Giovanni Spinola houses a bank. Palazzo Nicolosio Lomellino is home to a private association that organizes interesting exhibitions (such as the first monograph on Luciano Borzone, which we have also discussed on these pages) and cultural events. The palace that once belonged to Luca Grimaldi is now known as the Palazzo Bianco and is a museum headquarters: together with the Palazzo Rosso (which was never entered on the housing lists because its construction began seven years after the last roll) and the Palazzo di Nicolò Grimaldi (now the Palazzo Tursi) it forms the Strada Nuova Museum system. Several other buildings are the headquarters of private companies, public agencies, and offices; some are still inhabited. Many, unfortunately, have undergone interventions that have changed their original appearance, often radically. Still others no longer exist. There is, however, an interesting website, I Palazzi dei Rolli di Genova, which contains a complete list of all the buildings, subdivided according to the rolli to which they were inscribed and the bussoli to which they belonged, with all the details of the owners to whom they belonged at the time of inscription. Not all the palaces, however, have achieved UNESCO recognition (only a selection of forty-two of them became part of the World Heritage Site: these palaces are, moreover, described with rich apparatuses on the official UNESCO website). There are, however, another seventy or so that, while they cannot bear the coveted plaque, are certainly no less historically important than their more successful “counterparts.”

Reference bibliography

The author of this article: Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta

Gli articoli firmati Finestre sull'Arte sono scritti a quattro mani da Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta. Insieme abbiamo fondato Finestre sull'Arte nel 2009. Clicca qui per scoprire chi siamoWarning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.