Screams, terror and blood. On January 21, 1793, with the execution of Louis XVI (Versailles, 1754 - Paris, 1793), eight centuries of French monarchy were cut short in one day. The French Revolution had turned Paris into a theater of daily violence and spectacular public executions, while the cult of the guillotine permeated civilian life. In this climate of horror and tension, the basilica of Saint-Denis, a royal necropolis since the Merovingian era later expanded by Abbot Suger from the 12th century onward, became the target of revolutionary fury: the tombs, millennia-old demonstrations of the monarchy, were in fact destined to be opened, violated and stripped of all symbols of power.

The desecration of the royal burials was actually the culmination of a process that began even before the fall of the monarchy. Already on August 10, 1792, the day of thestorming of the Tuileries, the Abbey of Saint-Denis had been hit by acts of iconoclasm: the large portraits of the Count of Toulouse, the Duke of Penthièvre, the Duchess of Orleans and the Prince of Lamballe, works donated by Penthièvre himself, along with portraits of Louis XV and the queen, had been destroyed in March of that year. A few days after the abolition of the monarchy, the heraldic arms were also chiseled away because they bore fleurs-de-lis and crowns, emblems that had become intolerable in a France proclaiming the end of the dynasty. The Assembly also decreed the castingof lead, bronze andvarious metals from the tombs to make cannons from them, instruments of the new revolutionary war. In September 1792, the administrators of the department of Paris then reclaimed the keys to the crypt, in all likelihood to draw up an inventory of the coffins, and on September 23, with the official proclamation of the Republic, the statue of Louis XV was also dismantled, a gesture emblematic of a rupture that was now irreversible.

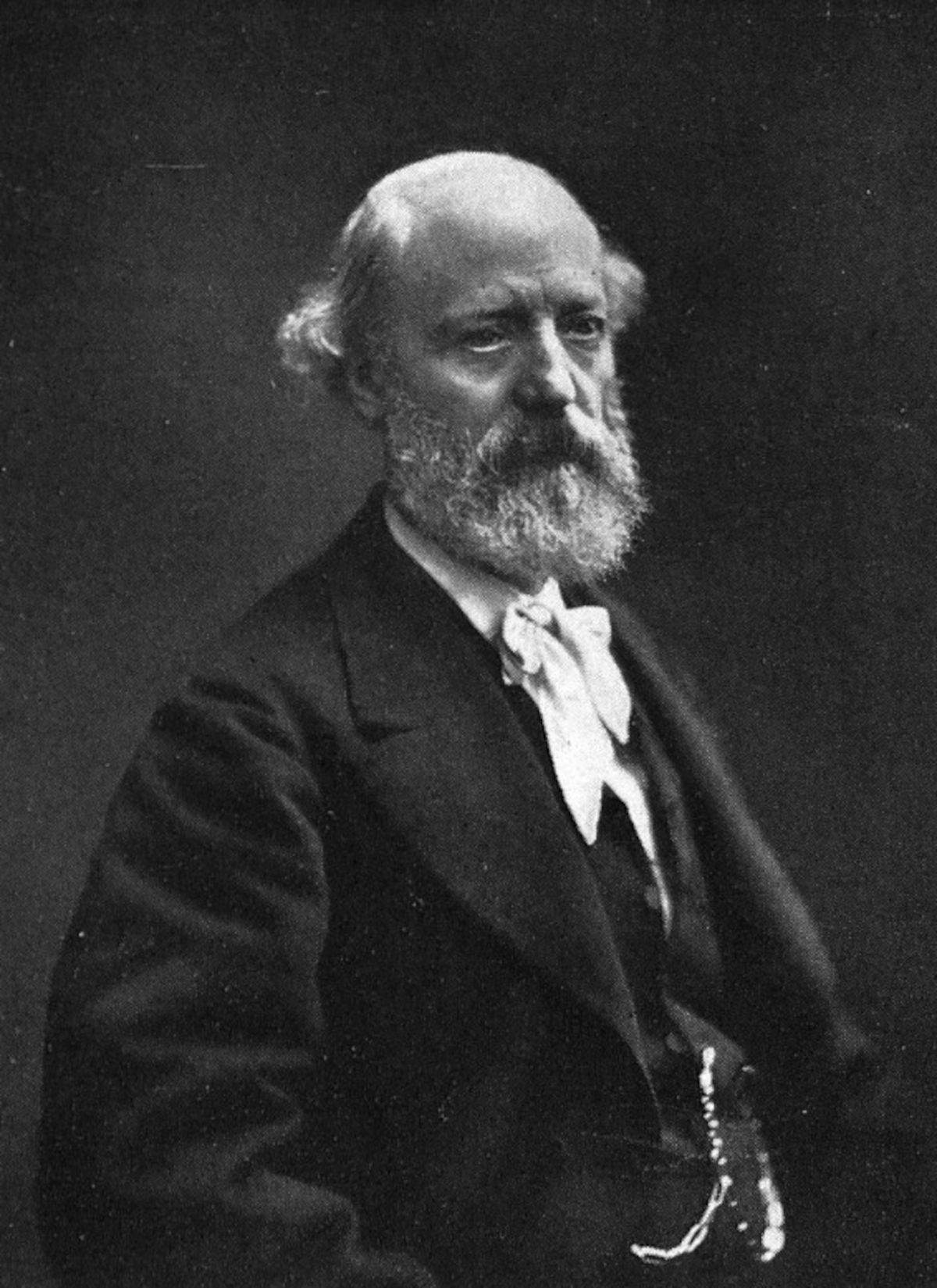

Thus, on August 1, 1793, on the first anniversary of the fall of the kingdom, the National Convention decreed the destruction of sepulchral monuments. The proposal, supported by Bertrand Barère de Vieuzac (Tarbes, 1755 - 1841), a French politician and revolutionary who was a member of the Convention (the revolutionary parliament), admitted no alternative: it was necessary to tear down the Saint-Denis monuments on August 10, since under the Old Regime even the tombs had learned to flatter the sovereigns. The ostentation of power, Barère argued (we know this thanks to the text Le mythe de saint Denis, entre Renaissance et Révolution by the French modernist historian Jean-Marie Le Gall), continued to shine through even from those mansions of death, and deceased kings still seemed to boast of a vanished grandeur. Indeed, as early as August 2, the municipality of Saint-Denis had ordered the destruction of the effigies kept inside the abbey.

The systematic demolition of royal symbols thus gave substance to a true damnatio memoriae, that is, it sanctioned the final exclusion of sovereigns from resting alongside their ancestors. On August 6, therefore, soldiers in red caps, workers armed with hammers and levers and a crowd of onlookers crowded into the basilica to witness the events. Among them was an eyewitness who left a record of what was happening. His name? According to Max Billard ’s descriptions given inLesTombeaux des Rois sous la terreur, he wasDom Druon, a former religious of Saint-Denis Abbey. A careful and silent man who followed the desecration work, noting everything down with great meticulousness. Indeed, to him we owe the account of the opening and violation of the royal burials (we also know that Druon did not leave the site until the work of desecration was completed).

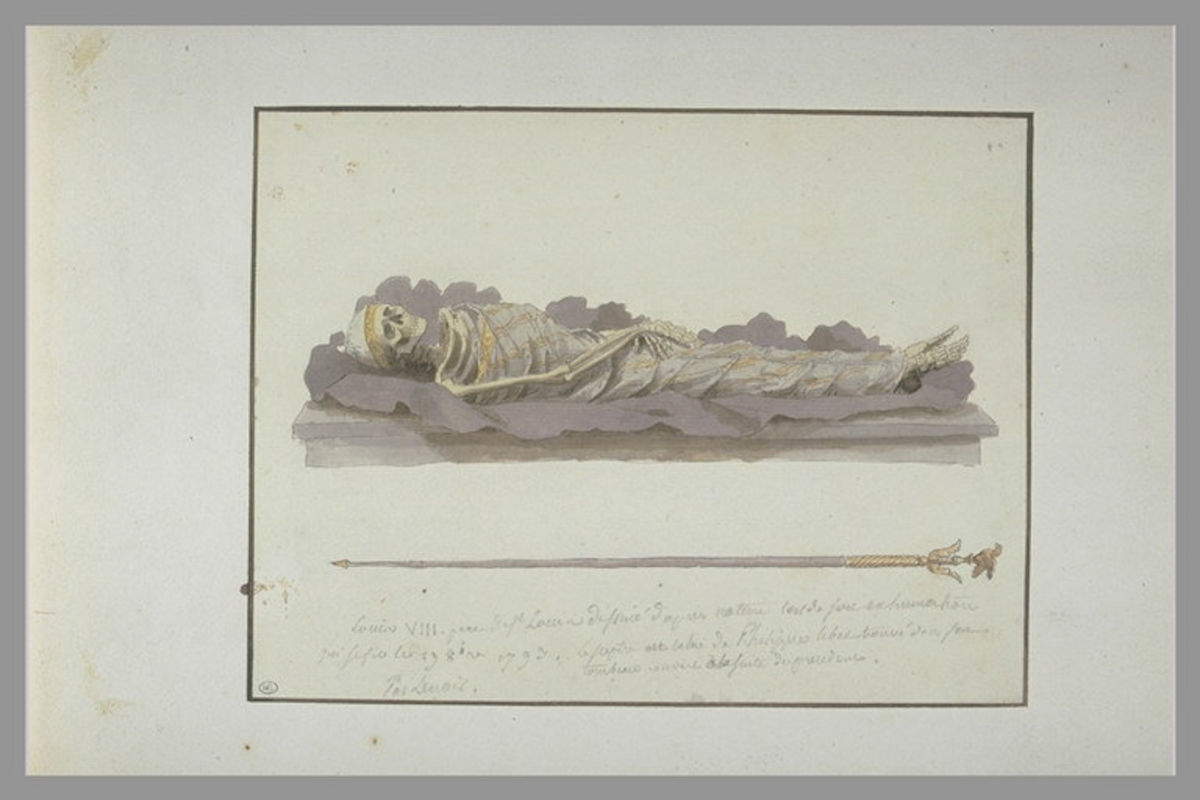

The first hammer blows resounded in the tomb of the abbey’s founder, the Frankish king Dagobert I ( 600 - 638), who was buried in the church on January 16, 638. The ogival monument of the king, placed next to the epistle, indeed retained a prominent role. The revolutionaries demolished the lying statue of the ruler, sparing instead the standing figures of Nantechilde and Clovis II. The three-tier relief illustrating a hermit saint’s vision of Dagobert I, which was then considered useful to art history and the human spirit, was also preserved. The sarcophagus remained closed and its opening was postponed until the October days. The revolutionary soldiers therefore devoted themselves to the tombs of Clovis II and Charles Martel. In this case the statues were not destroyed; they were simply removed from their bases. In fact, the sarcophagi contained only a few almost unrecognizable bone remains and a little ash, remnants of the long burial.

In contrast, the statue of Pippin the Short, son of Charles Martel, was lifted up: in the stone sarcophagus (crude and coarse, as reported by Billard), were ashes and a few gold threads, remnants of the worn funeral vestments. It was then the turn of the tombs of Bertha, wife of Pippin, Charlemagne’s brother Charlemagne I, Ermentrude, Louis III and his brother Charlemagne, Hugh the Great, Hugh Capetus, Henry I, Louis VI the Great, his son Philip, and Constance of Castile. All contained small sarcophagi, about a meter long, covered with slabs and filled only with bones. The destruction and reopening of the tombs of the Merovingians and Carolingians had not made a deep impression in Saint-Denis. True, those sovereigns appeared as legendary figures, but they were far removed from the time of the revolution. The sovereigns of that monarchy, with their effigies carved in prayerful poses and their eyes closed, lay in tombs that contained but a few remains, and in opening them the revolutionaries had not found much.

Far more shocking, however, were the days of October; events had indeed engraved on the tombs of the Bourbons dates impossible to erase. On Saturday, October 12, 1793, the same workers who had been working in the upper chapels of the basilica showed up accompanied by a commissioner, dressed in a black suit and hat with a tricolor cockade, and descended into the underground gallery to reach the Bourbon tomb. The gallery, sixteen meters long and six meters wide, in fact held the remains of Henry IV (Pau, 1553 - Paris, 1610) and his descendants, laid one after the other starting in 1610.

As Billard reports, entering “the empire of nothingness, where death and the transience of human glory triumph” was not so easy. Three slabs in the nave, next to the tombs of Philip III of France and Isabella of Aragon, closed off the access, which was completely walled off on the crypt side. The upper access, which was too narrow and inconvenient for the operations being planned, forced the revolutionaries to make a new opening. In fact, they worked between two Carolingian columns until, after hours of demolition, they managed to create a breach and break into the funerary enclosure. At that point the spectacle that presented itself inevitably aroused a sense of disquiet. Fifty-four oak caskets, covered in velvet or moiré (a type of silk) with silver fabric crosses, were lying on metal stands. In that environment rested the remains of Louis XIII (known as Louis the Just), Louis XIV (Saint-Germain-en-Laye, 1638 - Versailles, 1715) and Anne of Austria.

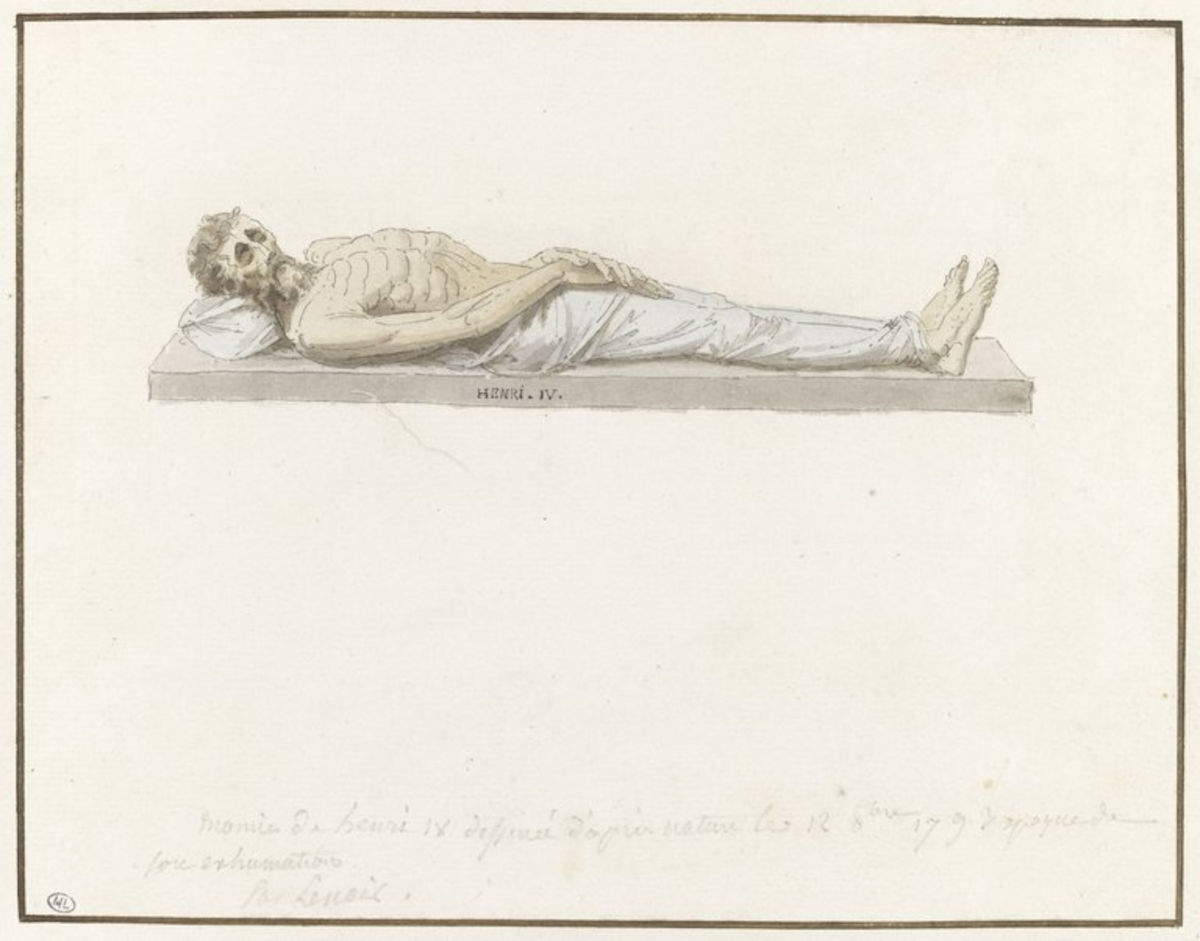

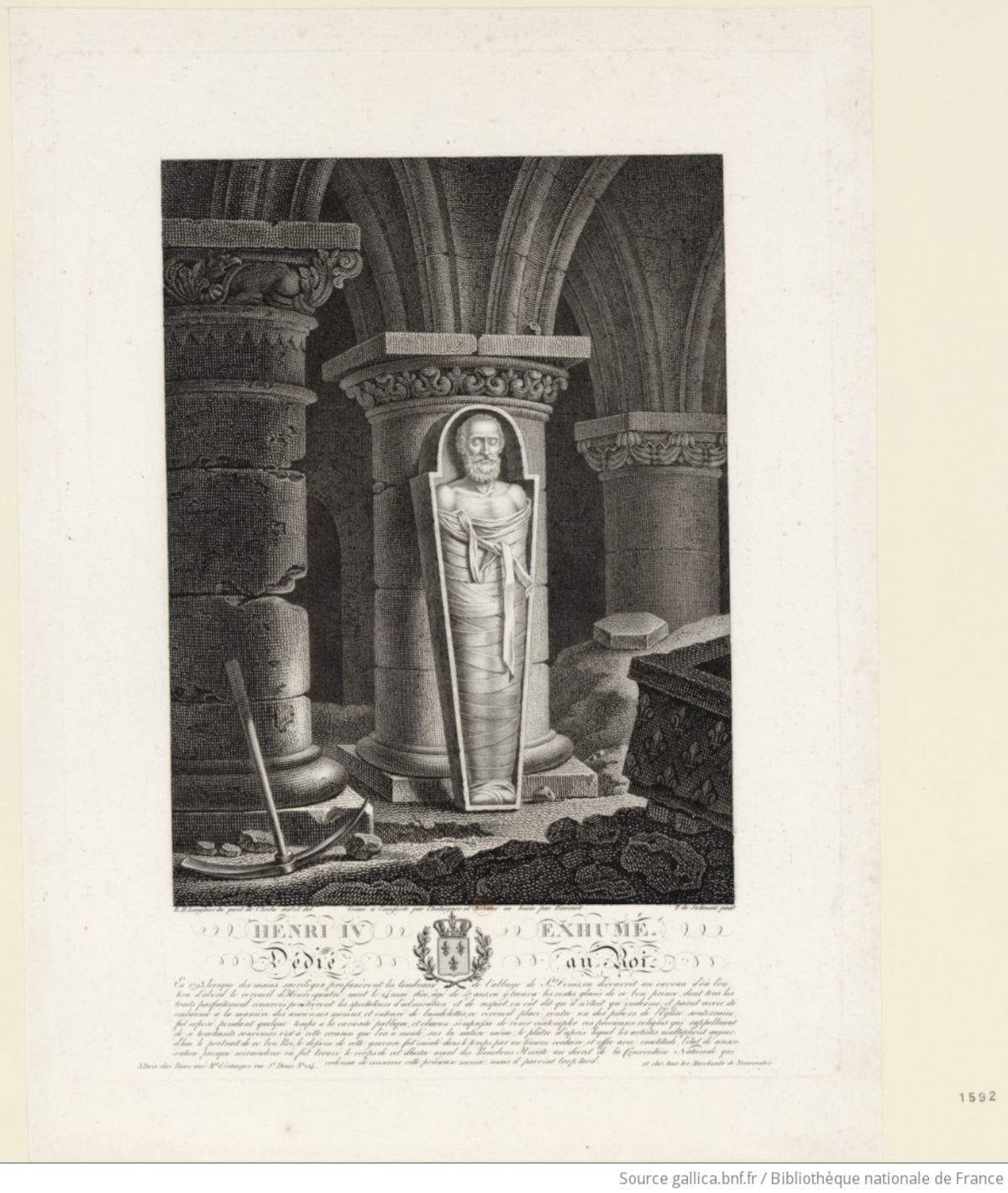

Operations began with the coffin of Henry IV, who died on May 14, 1610 at age 57. The first casket was destroyed with hammer blows; later (probably with the help of chisels), the metal sarcophagus was also opened. Inside, the shroud still appeared intact, and when the fabric was lifted, the surprisingly well-preserved body of the ruler emerged. Its recognizable profile and chivalrous appearance left no doubt as to its identity. The corpse was placed upright against a pillar at the foot of the crypt, where it remained on display until Monday, October 14, visible to anyone who wished to observe it. Billard also reports an additional detail.

During the display, a soldier (surely moved by patriotic fervor) approached, cut off a long lock of his still intact beard and, applying it to his own upper lip, proclaimed, “I too am a French soldier. From now on I will know no other stain. I am now certain to defeat the enemies of France, and I advance to victory!” There was no shortage of other symbolic and violent gestures. According to the writings of Druon and Billard, a woman instead struck the king’s face with a slap, causing his body to fall to the ground. Instead, a man extracted two teeth from the corpse, and another tore off a shirt sleeve, waving it around in the basilica. An artist decided instead to imprint the sovereign’s face in a cast: the funerary mask, made one hundred and eighty-three years after his death, has come down to us and is now preserved in several museums, including the Musée Carnavalet and the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, both in Paris.

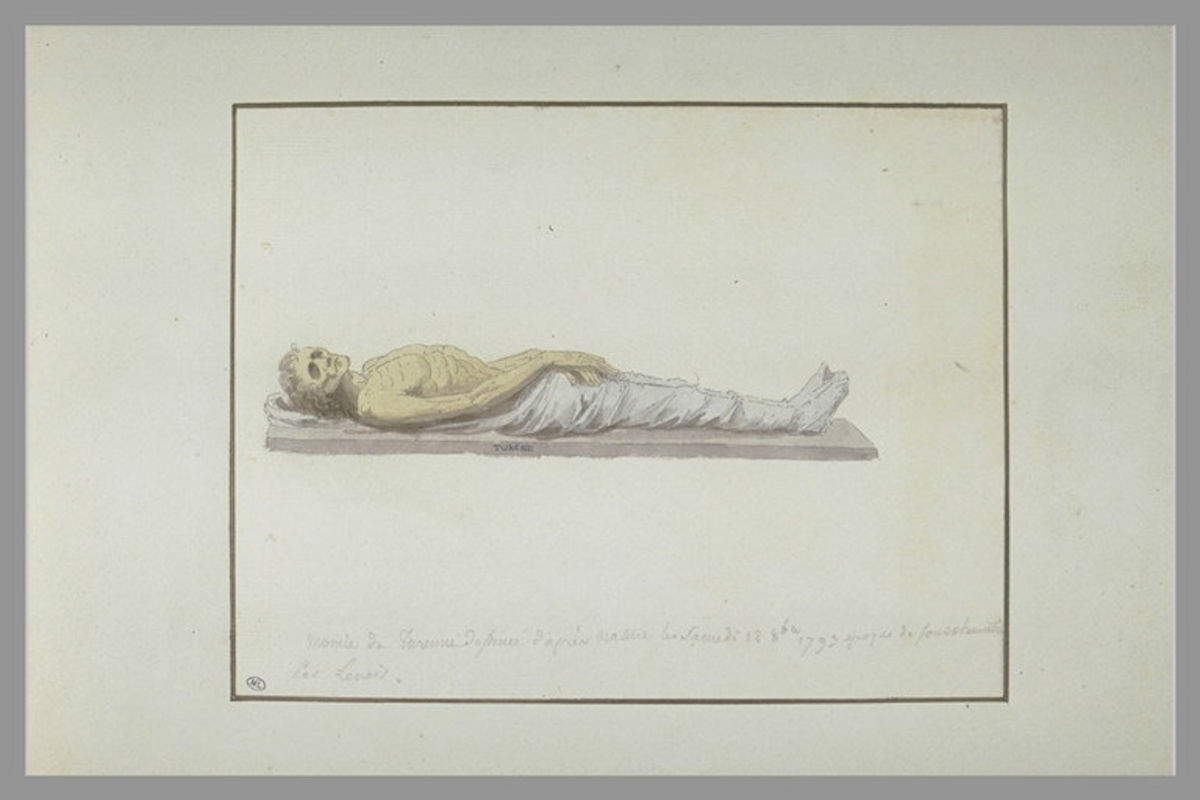

Two days later, precisely on October 15, the body was placed on top of a layer of quicklime in a vast pit dug in the Valois cemetery. In the afternoon, around three o’clock, workers proceeded to open Louis XIII’s coffin. The corpse showed more marked signs of deterioration, but the features remained identifiable mainly thanks to the thin, black mustache curled at the ends. Soon after was the turn of Louis XIV, the Sun King, remembered as “that Louis so well known for the obedience of nations.” Under the shroud his face appeared blackened and “black as ink,” but he still retained a stern yet majestic expression. It seems clear, then, that any attempt to symbolically safeguard the monarchy resulted: the bodies were thrown into the mass grave, and Louis XIV was laid over the body of Marie de’ Medici. The remains of Anne of Austria, Maria Theresa and the Dauphin Louis, son of the Sun King, were instead reduced to what Druon’s chronicles described as “liquid putrefaction.”

On the morning of October 15, men opened the coffins of Maria Leszczyńska (wife of Louis XV), Marie Anne Christine Victoria of Bavaria, wife of the Grand Dauphin, and nineteen other princes and princesses of the Bourbon dynasty. All the remains were transferred to the mass grave. From the accounts of the writers, we also know that under each coffin was kept a heart-shaped metal box containing the heart and viscera of the deceased, decorated with a crowned silver heart: the emblems were also removed and taken to the town hall, while vases and caskets were piled up in a corner of the cemetery. The whole operation offered a particularly repulsive spectacle. As already mentioned, most of the bodies were in an advanced state of decomposition, giving off nauseating vapors. What then to do to try to mitigate the odors? Vinegar and gunpowder were burned, which actually did not prevent many workers from falling ill with fever (without serious consequences, however).

Hubert Robert (Paris, 1733 - 1808), an artist already active during the Revolutionary years, documented the desecration of royal tombs with the oil painting The Breach of the Crypts of the Kings in the Saint-Denis Basilica in October 1793. Concrete evidence emerges from the catalog of the posthumous sale of his studio in 1809: two sketches appear within the register that have as their subject the demolition in the vaults of Saint-Denis. The work known today, the only one remaining by Robert, according to reconstructions, would be the ancient underground chapel of the Virgin erected in the 9th century by Abbot Hilduin and transformed in 1683 into the Bourbon crypt.

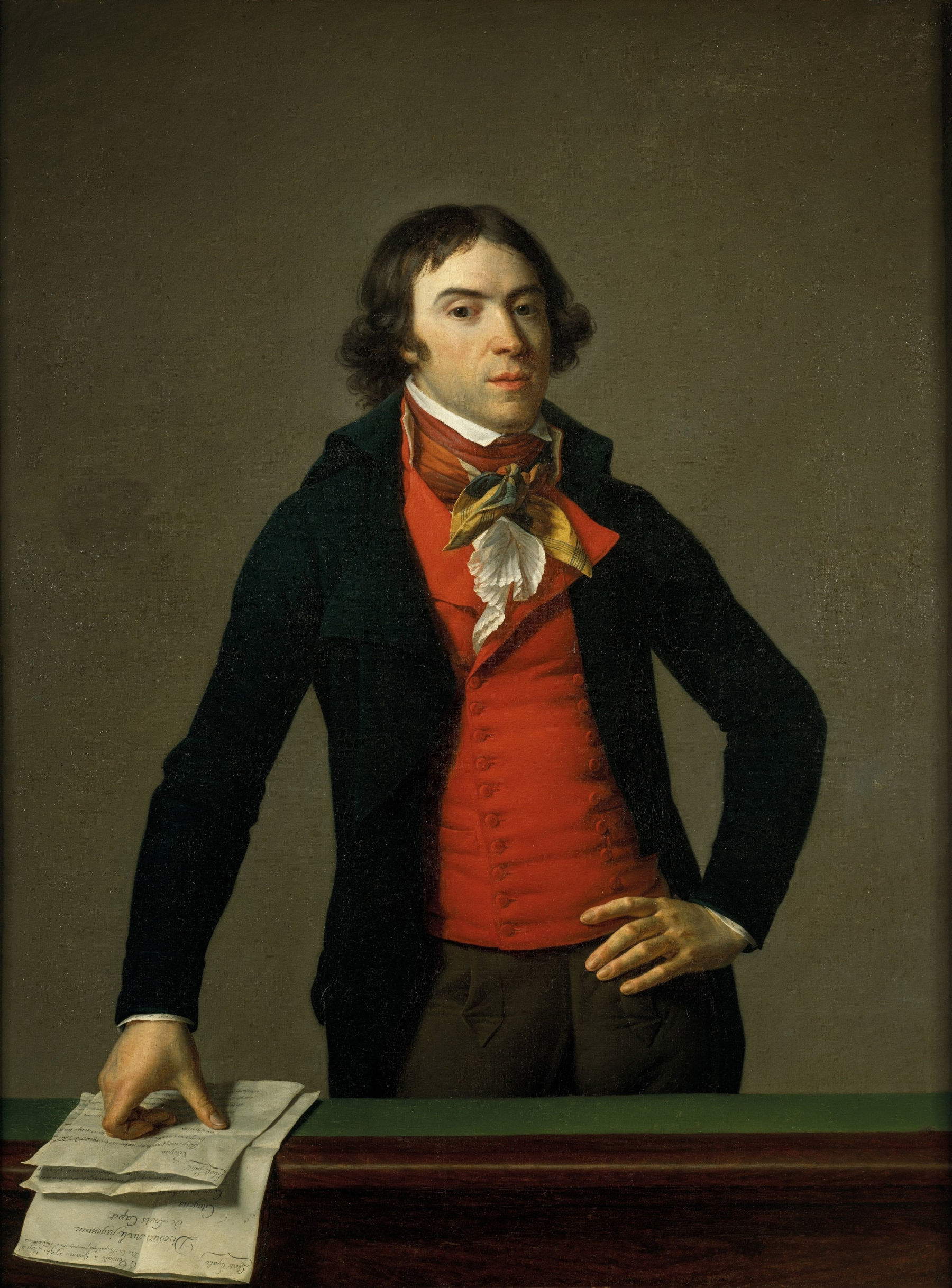

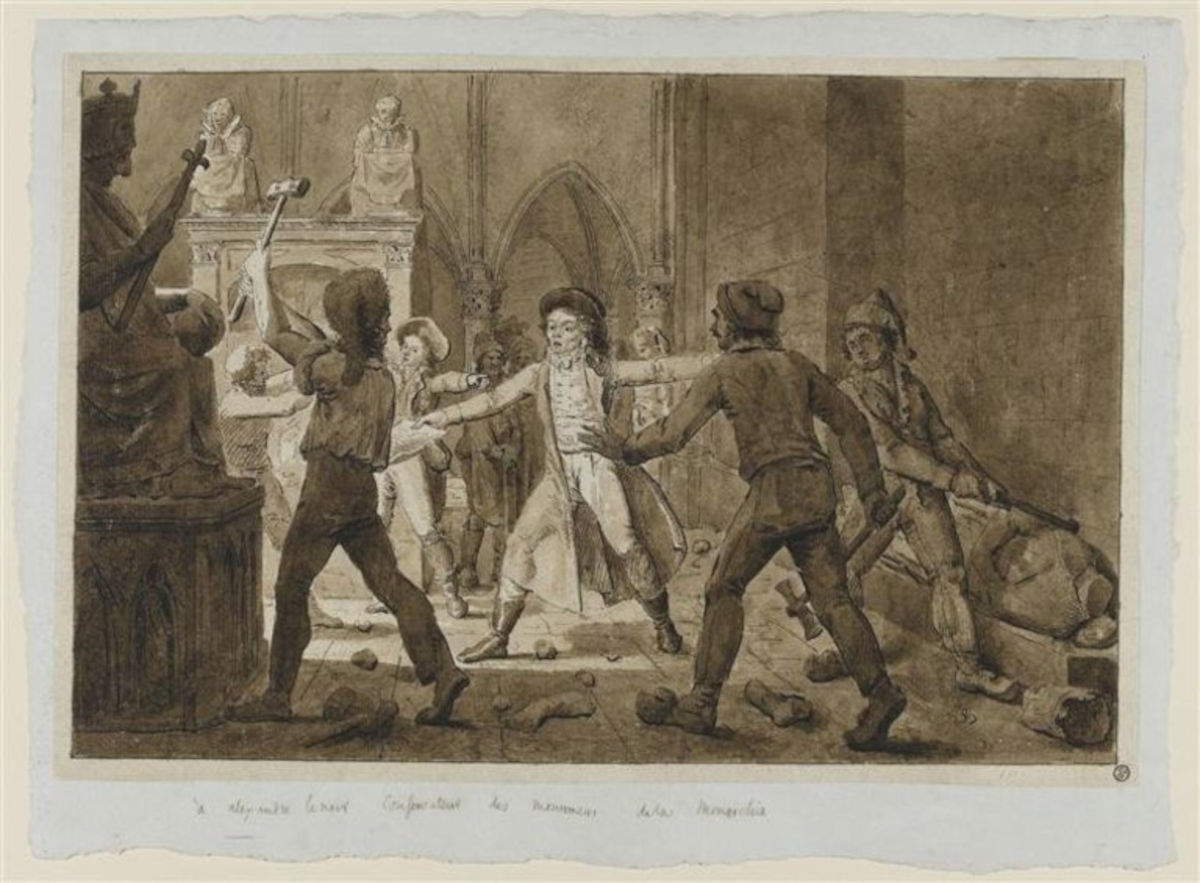

Robert’s artistic documentation was later joined by the direct testimony of Alexandre Lenoir (Paris, 1762 - 1839), director of the Musée des Monuments Français, who witnessed the pillage of the basilica’s burials. Lenoir resolutely opposed revolutionary vandalism, as shown in the drawing Alexandre Lenoir opposes the destruction of Louis XII’s mausoleum at Saint-Denis, carried out in October 1793 by Pierre Joseph Lafontaine. Thanks to his interventions, in fact, Lenoir managed to save several statues and other artifacts, transferring them to the Couvent des Petits-Augustins, which became in 1795 the Musée des Monuments Français (later closed in 1816). Among the works recovered by Lenoir are the funerary monuments of Louis XII and Anne of Brittany. Their preservation is documented by an oil painting (an anonymous one), dated between 1810 and 1820, depicting the mausoleum inside the museum’s 15th-century hall. Later, the monuments were restored and relocated inside the Saint-Denis basilica, partly recovering the memory of the royal sepulchres violated during the Revolution.

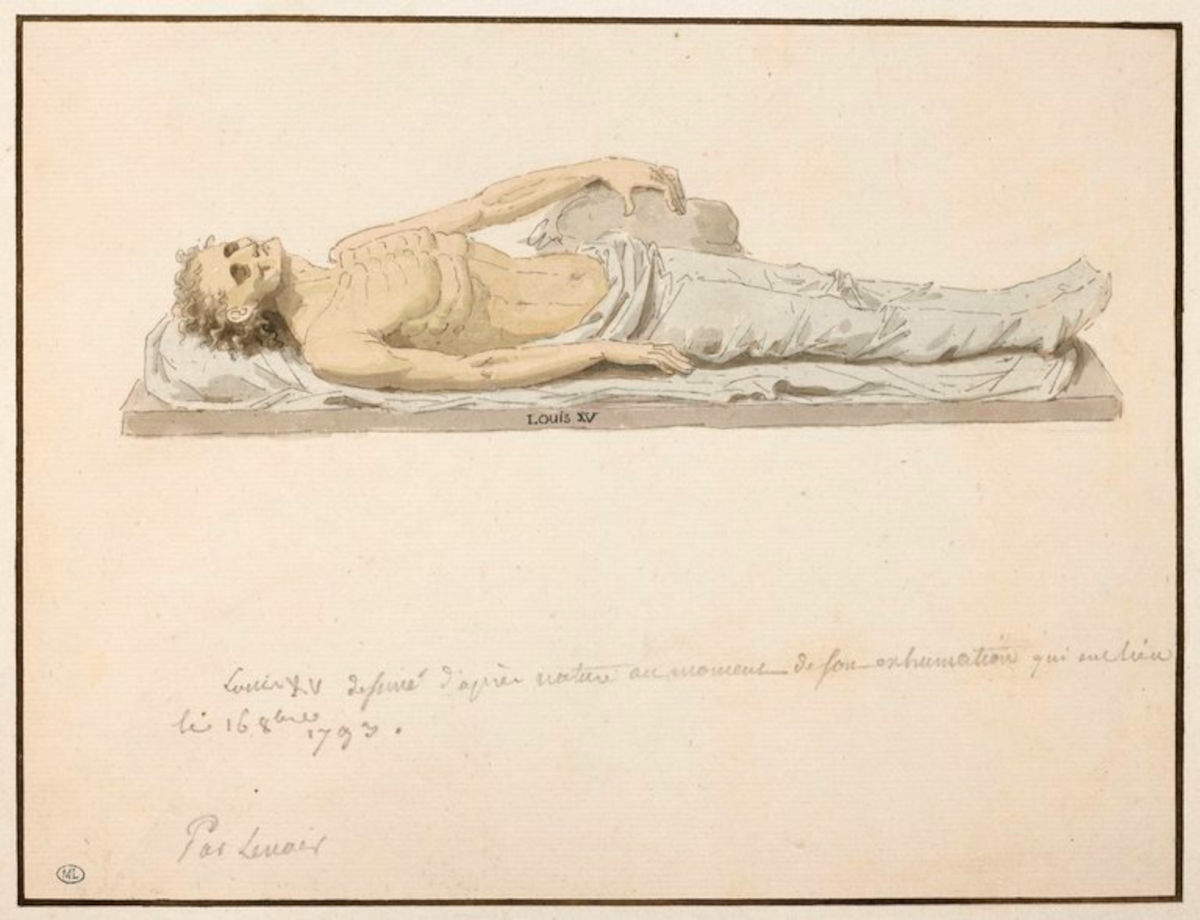

On Oct. 16, 1793, while in Paris Queen Marie Antoinette (Vienna, 1755 - Paris, 1793) was walking toward the guillotine, in Saint-Denis the revolutionary commissioners were continuing their desecration action. At dawn the coffins of Henri IV of France, daughter of Henry IV of France, Henriette of England, and Philip of Orleans, brother of Louis XIV, were opened, along with those of twenty other members of the dynasty. At 11 a.m. Louis XV’s coffin was moved, placed at the foot of a niche dominated by a statue of the Virgin. The metal sarcophagus was taken to the cemetery and opened only then. The first blow of the chisel, as Billard reports, released a jet of miasma so violent that it forced those present to back away while the body, immersed in a liquid derived from the dissolution of sea salt used for preservation, appeared surprisingly intact. The skin was still pale and the nose purplish. Louis XV, in fact, had not been embalmed according to traditional usage. In any case, once the protections were removed, decomposition manifested itself in all its severity.

As reported by Druon, the smell was so unbearable that gunpowder and gunshots were again resorted to in an attempt to purify the plague-ridden air. Eventually, the body was placed in the mass grave, laid on quicklime and covered with earth. The burial therefore remained open to accommodate the corpses of the following days. Meanwhile, inside the basilica, the sarcophagi themselves became targets of revolutionary fury. Bulky and difficult to stack, they were destined for casting. An improvised foundry was then set up in the courtyard, where the funerary sarcophagi were reduced to raw metal, ready to be reused. We also know that the work took place under inhumane conditions. The fumes from decomposing bodies saturated the air and made it unbearable to stay in the dungeon. To defend themselves, the revolutionaries resorted, as already written, to precarious remedies. In addition to gunpowder and sprinkling vinegar on the floor, men wore handkerchiefs soaked in aromatic substances on their faces. By the end of October, the royal burial ground at Saint-Denis was reduced to a desolate scene of ruins: the building, deprived of its function, remained exposed to the elements for years and knew a variety of uses. It was also used as a warehouse for flour and grain.

It was then Napoleon, at the beginning of the Empire, who decided to restore the basilica. On the advice of the politician Chateaubriand, he wanted to consecrate Saint-Denis as a new dynastic necropolis, destined for emperors, while recalling the memory of the ancient kings. By then, however, the revolution had scattered the remains of the sovereigns: what in fact survived of the pre-1789 burials had been thrown into two large mass graves in the northern cemetery of Saint-Denis, and the bodies no longer rested beneath their funerary monuments. Parallel to the sacking of the basilica, beginning in October 1792, the small cemetery of the Madeleine became the burial place for those executed on the Place de la Révolution, today’s Place de la Concorde. An estimated five hundred bodies were laid to rest there, including such notable figures as Olympe de Gouges, Manon Roland, Madame du Barry, Charlotte Corday, Philippe Égalité, and the twenty-one Girondin deputies. On January 21, 1793, Louis XVI was interred there, executed after a trial conducted by the deputies of the Convention; on October 16 of the same year it was Marie Antoinette’s turn, who was condemned by the Revolutionary Tribunal. Both were laid to rest in individual pits, the bodies enclosed in plain coffins and covered with quicklime.

With the Restoration, the Madeleine cemetery passed to Louis XVIII. On January 21, 1815, the foundation stone was laid for the Chapelle expiatoire, a monument intended to honor the memory of sovereigns guillotined. At the same time, the remains of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette were recovered and solemnly transferred from the Madeleine cemetery pit to the Saint-Denis basilica, thus returning the two martyred sovereigns to the dynastic necropolis from which they had been excluded by the Revolution. Work, slowed by the Hundred Days and Napoleon’s return, resumed after Waterloo and was carried out by architect Pierre Fontaine. Louis XVIII ordered that no clods of earth, impregnated with the blood of the victims, be removed. The ancient remains were therefore collected in charnel houses.

Inaugurated in 1824 and completed two years later under Charles X, the Chapelle expiatoire stood as a neoclassical monument with strong romantic and political overtones. It was a condemnation of regicide and a sign of monarchical revival. In 1817, moreover, Louis XVIII ordered the recovery of all the remains of the desecrated sovereigns, now mixed in the mass graves of Saint-Denis, to relocate them in an ossuary carved out of the crypt in the old vault of Turenne. After the July Revolution of 1830, the Chapelle expiatoire was threatened. In 1831, the decorations with the fleurs-de-lis were chiseled away, but three years later Louis Philippe of France decided to preserve it and only then had two large marble sculptural groups placed there: The Apotheosis of Louis XVI by François-Joseph Bosio in 1834 and Marie Antoinette Supported by Religion by Antoine-Denis Chaudet Cortot in 1835. The Chapelle expiatoire thus survived the political changes, erected as a religious and memorial symbol that linked private devotion, dynastic memory, and counter-revolutionary vindication.

With the return of the Bourbon monarchy and, later, with the start of the Second Empire, the basilica of Saint-Denis experienced a new season of attention. The building was gradually the subject of a restoration program that found its most influential guide in Eugène Viollet-le-Duc (Paris, 1814 - Lausanne, 1879), architect and restorer of sacred monuments. Indeed, thanks to his direction, many surviving medieval and Renaissance tombs were restored and relocated in the nave and chancel of the basilica, giving a new face of sacredness and memory to the dynastic complex. The crypt was enriched with stone statues of Carolingian emperors: in truth, there is talk of works made at the time of Napoleon I, with a view to an imperial chapel that was never completed. Saint-Denis thus became a place of political as well as religious stratification. At the same time, the cult of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette, found expression in new sculptural works commissioned during the Restoration. As early as 1816, Louis XVIII had ordered from Edme Gaulle and Pierre Petitot a monumental group also in marble depicting the two monarchs kneeling in prayer. The sculpture still present today in Saint-Denis, completed in 1830, shows Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette gathered before the altar, symbols of Christian and political martyrdom.

The affair of the desecration of the royal tombs at Saint-Denis was thus an expression of a precise political will: to destroy memory in order to erase an idea of power based on dynastic continuity. Indeed, the actions committed, from the dismantling of mausoleums to the casting of metals, from the opening of coffins to the dispersal of remains, obeyed a language that sought to translate the principle of popular sovereignty into concrete action. The basilica, thus became the stage for a condemnation of commemoration that spared nothing, neither bodies nor images. Yet Saint-Denis itself became a place of remembrance once again; the 19th-century restorations and the return of the royal remains gave new meaning to the revolutionary trauma. The basilica of Saint-Denis remains to this day a monument that, beyond its architectural beauty, remains concrete evidence of the line separating eternity from the ephemeral.

The author of this article: Noemi Capoccia

Originaria di Lecce, classe 1995, ha conseguito la laurea presso l'Accademia di Belle Arti di Carrara nel 2021. Le sue passioni sono l'arte antica e l'archeologia. Dal 2024 lavora in Finestre sull'Arte.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.