Painter, historiographer, architect. Outstanding collector of anecdotes. Polemicist at times. Court artist. And also inventor of iconographies. It is the latter, perhaps, that is the least known aspect of Giorgio Vasari (Arezzo, 1511 - Florence, 1574): the author of the Lives, the architect of the Uffizi, and the painter of Grand Ducal Tuscany had an extraordinary capacity to elaborate unpublished iconographies, and this quality of his could hardly be understood without having an idea of how Vasari imagined the figure of the artist. If one wanted to point to a founding element of his revolution, the real novelty of his aesthetic theory, one could identify it in the ambition, paraphrasing a remark by Paul Oskar Kristeller, to make painting share in the prestige of literature. For Vasari, the artist, hitherto considered little more than a craftsman despite the prestige that, at least since the mid-15th century, the society of the time had begun to increasingly attribute to painters, sculptors and architects, was to be considered on a par with a poet. The invention of new iconographies, which covered both sacred and secular subjects, beginning with the complex allegories that punctuate Vasari’s entire output, must be read in light of this ambition.

Among the many original iconographic inventions elaborated by Vasari, that of theAllegory of Patience certainly stands out, the subject of a careful study on the occasion of the exhibition that Arezzo has dedicated to its great artist on the occasion of the 450th anniversary of his death. The opportunity to devote himself to this subject came to him when, at the age of 40, in 1551 the bishop of Arezzo, Bernardetto Minerbetti, his friend and patron, commissioned a painting that would represent the virtue of patience in a new way that was allusive to his personal experience. There was already, in fact, an allegory of patience with well-established icongraphic content (Vasari himself had previously painted one for Palazzo Corner in Venice), but Minerbetti aspired to something else, something that summed up his experience as the nephew of a rich and stingy uncle who had put him through the wringer before he could inherit his wealth. A curious anecdote, in short, from which sprang one of the happiest inventions of the latter sixteenth century. But beyond this, the bishop nevertheless asked for a painting capable, Carlo Falciani wrote, of “representing the disposition of mind observed by him from his youth and chosen as his own emblem in maturity,” the disposition of a man capable of bearing pain and overcoming adversity. The bishop’s request implied an image capable of translating into visible form the feeling of one who, though tried, “tolerates et spetta con quella speranza che amaramente soffron coloro che stanno aagio per finire il loro disegno con patientia,” as Vasari would have written.

The iconographic invention that Vasari created for Minerbetti was the result of sophisticated reflection and significant intellectual collaboration: in addition to the painter from Arezzo, Annibal Caro, author of the Latin motto “Diuturna tolerantia,” and, at least in a consultative capacity, Michelangelo Buonarroti also contributed. The painting was completed in 1552 and depicts a half-naked young woman, exposed to the cold of a winter landscape, with her arms folded across her chest, as she watches a drop of water, falling from a vase-shaped clock, slowly burrow into the rock. “A splendid painting,” Cristina Acidini called it, “in which to denote the meaning of the beautiful, succinct woman will no longer serve the traditional yoke, a humble attribute of rural origin, but rather a precious water vase-shaped clock with a rod escapement, in coherence with gestures, environment and symbolic objects.” The artist would return to the theme several times; however, the original was recognized in a canvas now in the Klesch Collection.

It is an image that combines symbolic and naturalistic elements: thewater clock, an emblem of slowness and constancy, replaces the rustic yoke with which Patience was generally identified in iconographic tradition. The figure’s pose, reminiscent of that of the demure Venus, and her nudity, covered only by a robe that is nevertheless insufficient to mitigate the rigors of winter, allude to psychological and physical distress, restrained with composure. This is not a spectacular suffering, but a silent pain, manifested in the closed gesture of the body and the shivering of the skin exposed to the frost. The choice to express suffering through self-containment distinguishes this figure from other coeval allegorical depictions, which are often more narrative and theatrical.

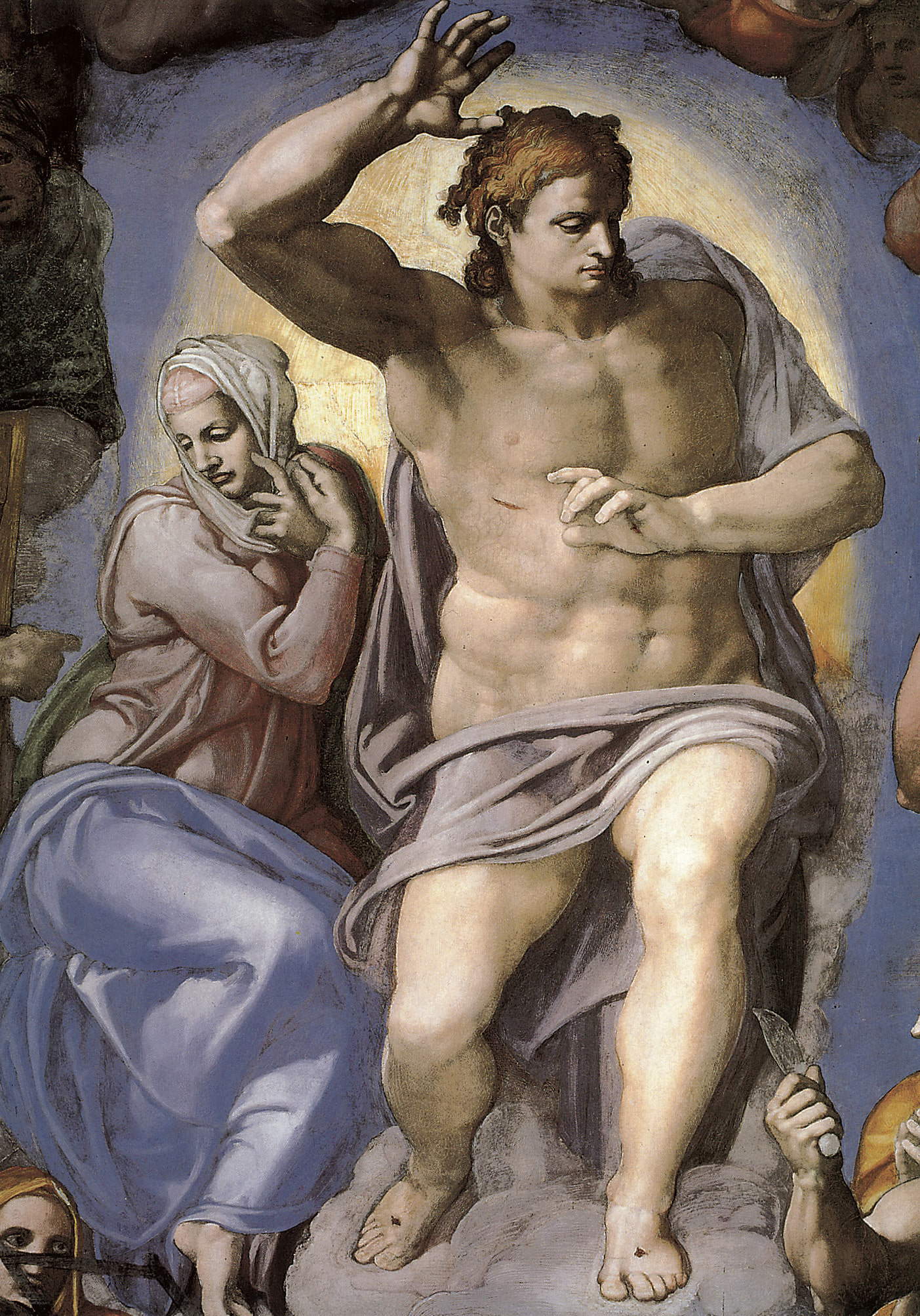

The reference to Greek pathos (from which the terms “passion,” “suffering,” and precisely “patience” are derived) is translated here into an image that, however idealized, communicates a sense of inner vulnerability. Vasari’s figure of Patience belongs to what has been defined by Acidini as an “iconography of the figure in discomfort,” which has significant precedents and parallels in the art of the time or earlier. These include Masaccio’s fifteenth-century Neophyte in the Brancacci Chapel, or Ammannati’sApennine-January (which is ten years later than the Patience but a product of the same cultural milieu), or Taddeo Landini’sWinter (also later, dating from the late sixteenth century), all of which are characterized by collected poses designed to protect themselves from cold or pain. Vasari, for his part, could also have drawn suggestion from two famous Michelangelo images: the Madonna of the Last Judgment, who crosses her hands around her neck, and the hooded figure in the Crucifixion of St. Peter, in the Pauline Chapel, who descends with folded arms.

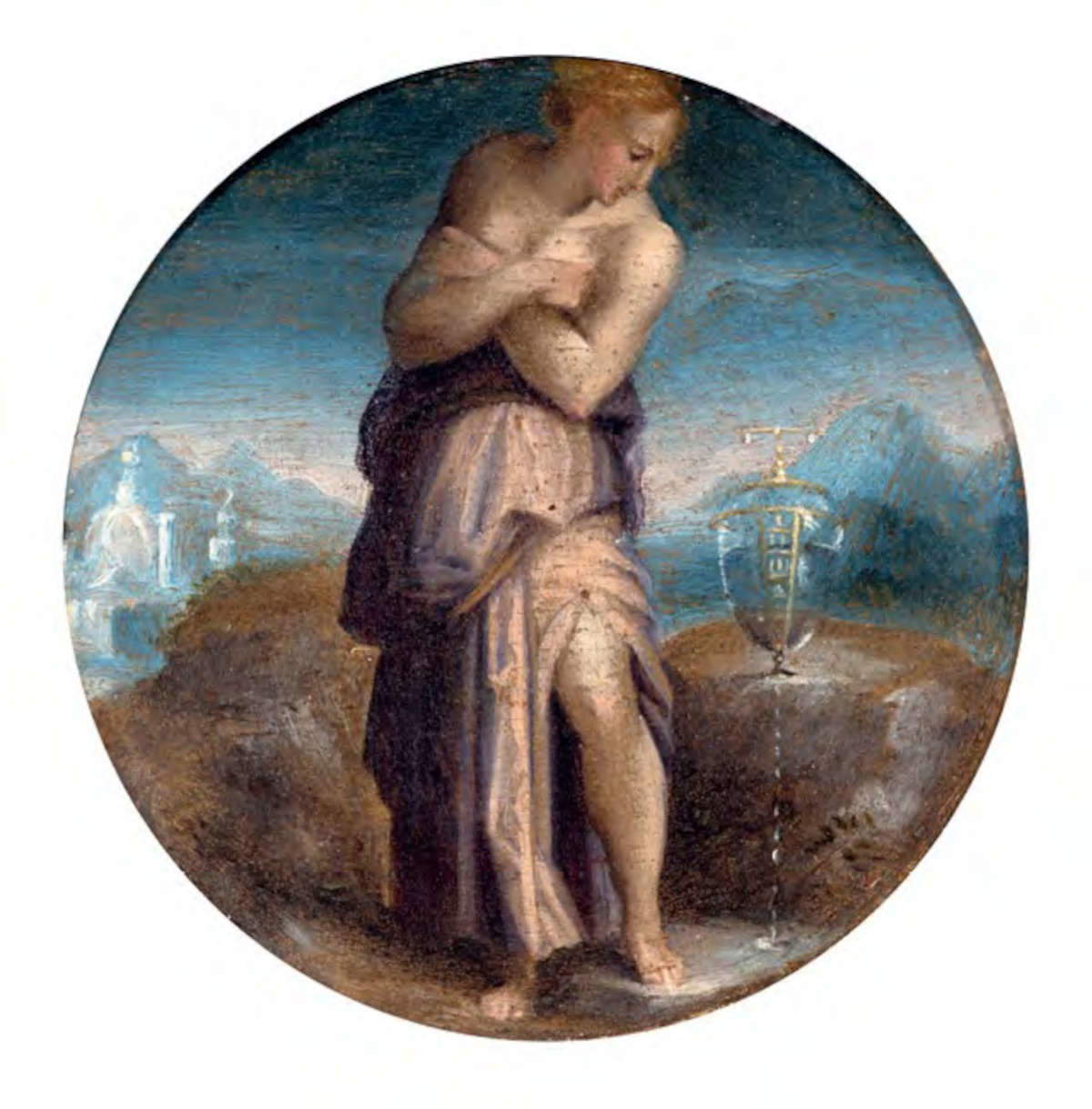

Vasari’s invention had considerable fortune and was the subject of replications and variations even during his lifetime. He himself made autograph versions of it, including a small oil-on-board panel, just ten centimeters in diameter, which went to auction in 2017 at Pandolfini, with attribution to Maso da San Friano and estimate 10-15 thousand euros. Today the work is considered an early, autographed variant of the original, probably executed for a Florentine patron (perhaps it was intended for a cabinet or perhaps, Falciani speculates, someone wanted to have theattestation of what at the time was considered an invention of Michelangelo’s), and it is very valuable because very rare are the autograph versions executed at this stage and so closely to the original. In this painting, recognizable architectural elements of the city of Florence appear in the background, such as Brunelleschi’s dome, the Campanile of Santa Maria del Fiore, and the Tower of Palazzo Vecchio. Missing, however, are the Latin motto and the chain on the figure’s left ankle, which Vasari had envisioned in a preparatory drawing but removed in the final version for Minerbetti. The choice to remove the chain probably corresponded to a semantic intention: Patience, although immobilized in time, is not a slave, but free in her choice to wait.

Then there is no shortage of thematic contaminations. Also by Vasari is an Allegory of Patience, owned by the Uffizi, which in the past was confused with the subject of Artemisia, Queen of Caria, famous for drinking her husband’s ashes: only the re-examination of iconographic and documentary sources has made it possible to re-establish the correct identification. Even in the small tablet, once attributed to Francesco Salviati, a derivation from the Vasarian model is now recognized, although the figure is caught in profile, and in a pensive attitude reminiscent of the Musa Polymnia of ancient sarcophagi, rather than the demure Venus that inspired the original.

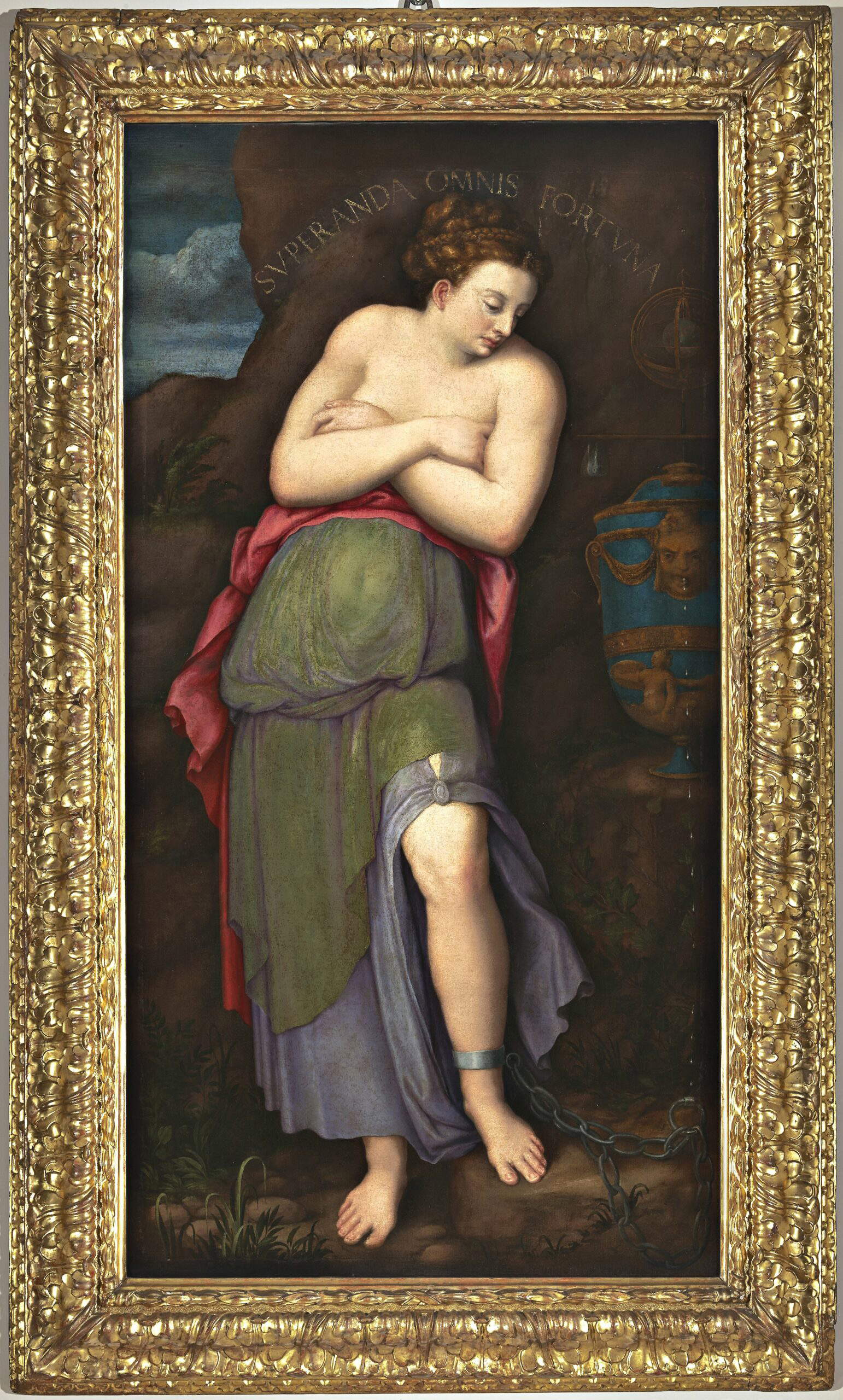

The fortune of Vasari’s image then spread far beyond the Florentine sphere. A notable example is from the court of Ferrara, where the Pazienza was adopted as a personal feat by Duke Ercole II d’Este. A medallion of the time designed by Pompeo Leoni depicts a female figure, with arms folded and wearing a light robe, chained to the rock, next to a pitcher from which water drips under an armillary sphere. The inscription reads “superanda omnis fortuna,” a Virgilian quotation that emphasizes the power of virtue in overcoming adversity. Vasari’s transposition was thus adapted to the political and cultural values of the Ferrarese court. The result was pictorial versions, such as the one executed by Camillo and Sebastiano Filippi for the Camera della Pazienza in the Galleria Estense in Modena, and even variants on medals and art objects.

The story of the spread of the Allegory of Patience is also the story of its attributions. For example, there is a famous version of it, also made in the Este domain (because of the armillary sphere and the motto “superanda omnis fortuna” that, as we seen, characterize the medallion of Hercules II), and now preserved in Palazzo Pitti, which in the past was erroneously assigned to Parmigianino, Francesco Salviati, Giuseppe Porta and even Vasari himself, before the discovery of the painting now in the Klesch Collection reopened the debate around this work. However, modern studies, supported by documentary and stylistic findings, had already traced the authorship of the invention back to Vasari, specifying that in some executions he used collaborators, and that not all the pictorial variants were painted by him personally. The version preserved in the Pitti Palace, which, moreover, bears the depiction of the chain holding the young girl to the rock, is, according to Anna Bisceglia, to be attributed to the Ferrarese circle of the Filippi family, and more specifically to Sebastiano Filippi known as Bastianino, on the basis of the plastic construction of the figure and the particular articulation of the drapery (“the style of the work,” Bisceglia wrote, “stands out for its characters of effused softness that push it toward the Ferrara series whose first exemplar is the one executed by Camillo and Sebastiano Filippi for the Camera della Pazienza commissioned by Hercules II and today preserved in the Estense Gallery in Modena”). It is, after all, a work very close to the one preserved at the Estense Gallery.

Among the most interesting and complex derivations of Vasari’s iconography is a panel painting by Giovanni Maria Butteri from the 1660s, which recently went on sale at Koller, where it was sold in 2022 for the sum of 171,000 Swiss francs (about 180,000 euros). In Butteri’s painting, the figure of Patience retains the original Vasarian pose, chained to the rock in patient waiting, but is surrounded by completely different attributes that amplify the allegorical meaning. Time is no longer represented by the water clock, but by a star medallion containing an uroboros, the serpent biting its tail, a symbol of eternity and temporal circularity. In the center appears Kronos-Saturn in the act of devouring one of his sons, an image that traditionally evokes destruction but in this context takes on positive significance, alluding to the return of the Golden Age. Behind the figure stands the chariot of Apollo rising spurring the horses upward, symbolizing the rebirth of the day and hope. This element, Carlo Falciani argues, is related to the branch sprouting from the cut trunk supported by the woman, a probable reference to the Medici broncone, the emblem of rebirth adopted by Lorenzo the Magnificent after the death of his brother Giuliano in the Pazzi conspiracy of 1478. The sprout, with leaves that may be olive rather than laurel, recalls the Laurentian motto “Le temps revient ”and Virgil’s prophetic fourth egloga, where the return of a new golden age is announced. The symbolic complexity of the work is completed by the presence of a scorpion in the lower left corner, which could be a symbol of deception or fraud and which, connected to the chain, could allude to the patience needed to overcome the impediments that can bind man. The dating of the work to the 1860s, during the adult life of Francesco I de’ Medici, suggests a possible connection with dynastic events.

However, Butteri’s work is an eloquent example of how Vasarian invention had become an open model, capable of accommodating new meanings and adapting to specific political and dynastic contexts. The freedom with which the Florentine artist combined symbolic elements that had not yet been codified shows that theAllegory of Patience had indicated “to mid-century Florentine artists,” Falciani explained, “the possibility of creating new allegories untethered from the ancient tradition.”

The success of theAllegory of Patience testifies with still vivid evidence to the maturity Vasari had reached after his travels around the peninsula, his Venetian experience, and his familiarity with ancient sources and his contemporaries. By now the artist could compete with the greatest minds of the time in creating artistic inventions destined to cross geographical and temporal boundaries, influencing generations of artists throughout Europe.

TheAllegory of Patience was thus not just an exercise in style, but a kind of conceptual construction, in which Giorgio Vasari knew how to condense moral tension, iconographic invention and formal language. It was also a significant example of his ability to respond to patrons with personalized and sophisticated solutions, in dialogue with ancient heritage and contemporary artistic thought. In the union of content and form, this figure ended up representing not only a virtue, but an entire existential posture.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta

Gli articoli firmati Finestre sull'Arte sono scritti a quattro mani da Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta. Insieme abbiamo fondato Finestre sull'Arte nel 2009. Clicca qui per scoprire chi siamoWarning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.