Almost all of the lost frescoes of the Salazar Chapel, a masterpiece by Giovanni Battista Trotti known as Malosso (Cremona, 1555 - Parma, 1619) that could once be seen in the Capuchin church in Regona, a hamlet of Pizzighettone (Cremona), where Don Diego Salazar (Huete, c. 1537 - Milan, 1627), a Spanish diplomat who held the position of Grand Chancellor of the State of Milan at the end of the 16th century, wanted to have his heart preserved, and to that end he commissioned Malosso not only to decorate the chapel, but also the Salazar triptych that was recently brought together in the exhibition organized between Piacenza and Cremona. Author of the discovery is young art historian Beatrice Tanzi, from Cremona, class of 1991, who published the findings in the volume Malosso for the Heart of Don Diego de Salazar, recently released by Edizioni Delmiglio. This is a significant contribution to the study of late 16th-century Cremonese painting as it offers new perspectives on the figure of Malosso.

The Regona painting cycle represents a cornerstone of Malosso’s production. Tanzi’s research starts from his work in cataloguing the Salazar Triptych conducted on the occasion of the aforementioned exhibition, entitled Il Cavalier Malosso. Un artista cremonese alla corte dei Farnese and held between the Musei Civici di Palazzo Farnese in Piacenza and the Museo Diocesano in Cremona in the spring of this year. The Regona chapel, dedicated to St. Ambrose, was commissioned, as mentioned, by Don Diego de Salazar, Grand Chancellor of the State of Milan, Count of Romanengo and later president of the Supreme Council of Italy. This Spanish official had established close ties with Pizzighettone and Regona for private, family and economic reasons: in fact, he had some estates in the area and was very attached to this territory, so much so that he even promoted the foundation of a convent on the road that joined precisely Regona to Pizzighettone. The most striking peculiarity of the chapel lies in the fact that it was not intended to contain the body of the Grand Chancellor, buried in the chapel of the Rosary in San Bassiano in Pizzighettone, but rather his heart, preserved in a vase inside a specially constructed urn. A practice, that of the burial of the heart separate from the rest of the body, widespread between the Middle Ages and modern times, aimed at expressing a spiritual bond with a place particularly dear to the deceased.

The chapel, originally part of a Capuchin monastery that was later suppressed and destroyed in 1810, managed to survive for a time as a small church in its own right, admired and accurately described in the late 19th century by a local scholar, Cirillo Ceruti. It was his meticulous description in 1902, before the chapel was also demolished after being stripped of its treasures, that formed the basis for Beatrice Tanzi’s work of recomposition.

The centerpiece of the pictorial complex was the Salazar Triptych, the “speciosa tabula” recorded in Salazar’s will, made by Malosso in 1595. The triptych, mentioned in the 1600 testament of Don Diego de Salazar, consisted of a central altarpiece, theAdoration of the Shepherds, and two side panels depicting Saint Sebastian and Saint Diego of Alcalá. TheAdoration, signed and dated “Malossus faciebat 1595,” is now part of the collection of the Banca di Piacenza, while the two side panels, also from 1595, were recently traced to a private collection by Beatrice Tanzi, after traces of them had been lost for decades until they recently reappeared in an auction at Cambi’s in Genoa, with erroneous attribution and incorrect dating (they were in fact believed to be the work of the “19th-century Cremonese school,” with an estimate, moreover, low, 5-6.000 euros the pair: they were later sold at 30,100 euros including royalties). Already Desiderio Arisi, in the early 18th century, had attested to Malosso’s authorship and interpreted the laterals as portraits, recognizing in Saint Sebastian the son of Salazar and in Saint Diego the same Don Diego. However, more recent research has called these identifications into question, especially in light of the discovery of an authentic portrait of don Diego de Salazar (dating from about 1589-1590, thus predating the triptych) at the Barbara Melzi Canossian Institute in Legnano, attributed to a Cremonese painter from Malosso’s circle. This portrait, with its stern and solemn physiognomy, definitively rules out the identification of Salazar with figures such as the bearded shepherd in the Regona painting or with Saint Diego, suggesting that any portraits in the side panels must be understood in an ideal sense, linked to the identity of the patron saint. The central altarpiece, with its crowded and skillfully organized composition of shepherds and bystanders around the Virgin, shows echoes of the manner of Bernardino Gatti known as Sojaro, or more generally, a neo-Correggesque imprint. The side panels, particularly the St. Sebastian, reveal Malosso’s aptitude for the total immersion of his characters in nature, with a “modern and magical, Flemish-style” landscape, taken from Sojaro, characterized by remarkable chiaroscuro wisdom.

The Regona Chapel fits into a moment of important illusionistic and perspective inventions in the career of Malosso, a leading artist between Lombardy and Emilia in the transition between the 16th and 17th centuries. Giovanni Battista Trotti enjoyed a wide network of ecclesiastical commissions, which led him to work from Umbria to western Liguria, with significant sojourns and works in various Italian cities such as Brescia, Venice, Genoa, Milan, Lodi, Pavia, Parma, and Piacenza. His activity was not limited to painting, extending to architecture as well, as evidenced by his designs for the New Cathedral in Brescia and the altar of the Blessed Sacrament in Cremona Cathedral. His relationship with the Capuchin order was particularly intense, with works created for male and female convents in various locations. In Regona, in addition to the Salazar Triptych, he had also painted another masterpiece, the high altarpiece with the Madonna in Glory and Saints Francis and Ambrose (1590), now in Soresina. The Salazar chapel, in its small size, testifies to his quadratural and pictorial mastery.

The discovery of almost all the wall paintings of the Capuchin chapel, torn down by the 1920s by engineer Ettore Signori, and long preserved in two private collections, thus allows us to get a clear idea of this important decorative apparatus that survives today in fragmentary form. These frescoes, although mentioned episodically, had never before been reproduced and analyzed in such depth, and their recomposition opens up new horizons both from the figurative point of view and in terms of commissioning and research methodology. Ceruti had left a precise description of the frescoes, and this description allowed Tanzi to identify and place the surviving episodes (two fragments, moreover, were displayed at the Piacenza exhibition alongside the Salazar triptych).

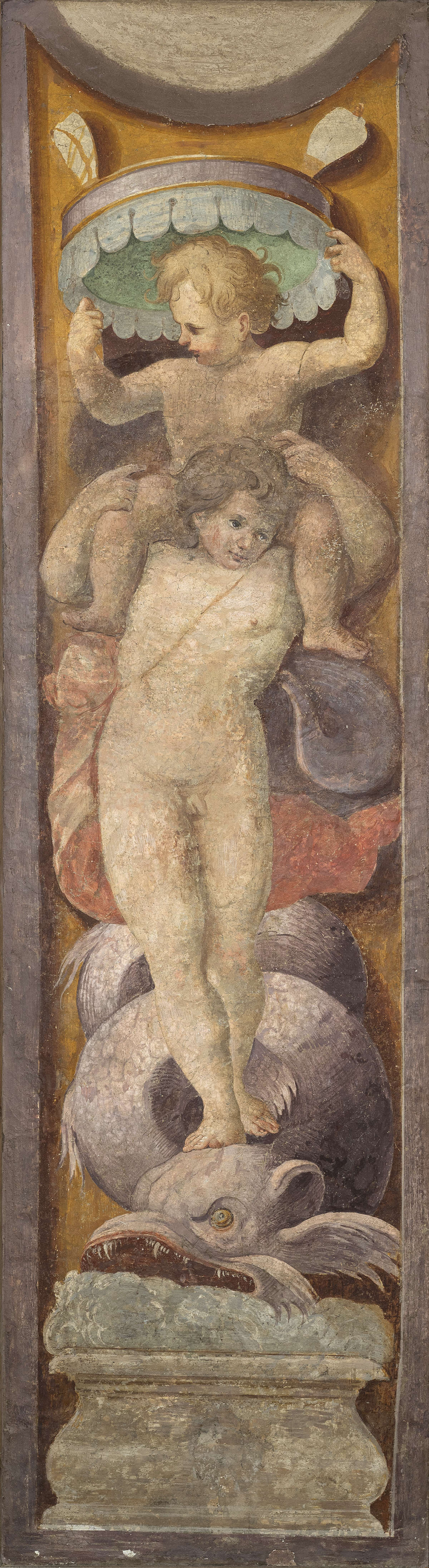

Among the recovered artifacts are several sections of the vault and walls. The vault featured four supports decorated with finial caryatids in masks, between which four winged putti supported the Cardinal Virtues: Prudence, Justice, Temperance and Fortitude. Of these, Temperance has been recovered, while Justice and Prudence are found, in poor condition, in the storerooms of the Ala Ponzone Civic Museum in Cremona (they are, the latter, the two fragments that were exhibited in Piacenza). Above the altarpiece was depicted a head of the Eternal Father, and above the entrance archway a seated prophet with a book, a fragment of which was unfortunately found stolen and lost. On either side of the windows, two holy virgins (or sibyls) were found. In the center of the circular cornice, a group of angels in glory admired a “holy child” crowned with flowers, a roundel also recovered. The pilasters with putti and monsters (crocodile and dragon), mentioned by Ceruti, have been traced and are based on models by Bernardino Campi.

The side walls housed four Stories of St. Francis: on the right wall, entering, were the episodes with St. Francis turning money into snakes and St. Francis renouncing earthly goods. On the left wall were the Temptation of St. Francis and the Mystical Ecstasy. In the entrance sub-arch was the Apparition of St. Francis on a chariot of fire, with the emblem of the Franciscan order. These episodes, taken from Bonaventure of Bagnoregio’s Legenda Maior and Thomas of Celano’s Lives of St. Francis, show Malosso in an unprecedented form, balanced “between lively narrative spontaneity and sophisticated decorative cadences,” Tanzi writes.

Stylistically, the Franciscan scenes reveal a singular and surprising dimension. At first glance, in fact, they might seem less immediately attributable to the hand of the Cremonese painter, so much so that Ceruti had attributed them to an “unknown author.” One can see, Tanzi explains, a definite focus on the Roman scene and international Mannerism. The pictorial drafting is typically Malossian, but the compositional setting departs from the usual crowding in the painter’s contemporary works. In almost every scene, with the exception of the Renunciation of Goods, there are only two figures, of monumental scale and pregnant iconic value, filling the space to the exclusion of all unnecessary trappings. This can be explained by a specific Franciscan iconographic program, probably suggested by the patron, which seems to be based on the use of engraved models of central Italian matrix, still partly to be identified. Ongoing studies by the Cremonese scholar indicate probable references to artists such as by Raphael Sadeler and Philip Galle; for example, theMystical Ecstasy finds its prototype in an engraving by Sadeler, while the temptress woman in the Temptation scene seems to derive from a 1587 engraving by Galle. This Roman influence and widespread dissemination of prints, corroborated by Bernardino Campi’s donation of more than 2,500 prints to Malosso in 1575, suggest a possible, though as yet undocumented, sojourn of Malosso in Rome in the first lustre of the last decade of the 16th century, a period of exceptional artistic fervor under the pontificate of Sixtus V, the Franciscan pope.

The discovery of these four scenes from the saint’s life is of particular significance, as they represent “a sort of unicum in Malosso’s activity and induce non-trivial methodological reflections,” explains Tanzi, according to whom, however, Malosso’s full autography can be confirmed, both stylistically and inventively, and because of “the very high prestige of the patron.” Although some gaps remain, such as the “stupendous head of Padre Eterno” or the original carpentry of the altarpiece, and the stucco decorations, Tanzi has managed to recover almost all the erratically dispersed material that composed the environment desired by Don Diego Salazar. The study, therefore, makes it possible to give new visibility, explains scholar Valerio Guazzoni in the booklet’s preface, “to the happy conjunction created in Regona between patron and artist, an understanding that left a relevant mark on the pictorial events in Cremona in the late 16th century.”

|

| Forgotten for over a century, Malosso frescoes return to light |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.