“Arte Povera” is understood to mean an art movement that originated in Italy in the 1960s, and to which many artists destined to become among the greatest and most influential of the 20th century joined, such as Giulio Paolini, Pino Pascali, Luciano Fabro, Jannis Kounellis, Mario Merz, Michelangelo Pistoletto and several others. The birth of the movement can be made to coincide with the first exhibition of “poor artists” held in 1967 in Genoa, at La Bertesca gallery, while the term was coined by art critic Germano Celant (Genoa, 1940 - Milan, 2020), considered the theoretician of the movement, who used it in his 1967 paper Arte povera: appunti per una guerriglia, published in Flash Art magazine.

The name “Arte Povera” refers both to the materials that poor artists used (i.e., humble materials, such as papier-mâché, salvaged iron, rags, recycled objects, wood, earth, plastic, and so on) and, above all, to the fact that the movement’s intent was to stand in opposition totraditional art and to elaborate a language that could reduce to the essential, to “impoverish” the work in other terms, and that was more suited to that of contemporary society.

“A poor art, engaged with contingency, with the ’event, with the ahistorical, with the present,” Celant had written in Arte povera: notes for a guerrilla warfare, “with the anthropological conception, with the ’real’ man (Marx), the hope, which has become security, of throwing to the nettles any visually univocal and coherent discourse (coherence is a dogma that must be broken!), uni-vocity belongs to the individual and not to ’his’ image and its products. A new attitude to possess a ’real’ domain of our being, which leads the artist to continuous displacements from his deputed place, from the cliché that society has stamped on his wrist.”

The Arte Povera movement was officially born in 1967 when the first exhibition was held at La Bertesca gallery in Genoa, at 13R Via Santi Giacomo e Filippo: the gallery had been founded just the year before by Francesco Masnata and Nicola Trentalance, aged 25 and 24 respectively. Entitled Arte Povera - Im Spazio, the exhibition displayed twelve artists, each present with a work (all the works had been made that year): Alighiero Boetti (with Catasta, sixteen eternit tubes with a quadrangular cross-section that formed a parallelepiped), Luciano Fabro (with Pavimento from 1967, an installation of linoleum squares covered with newspaper sheets), Jannis Kounellis (with Senza titolo, a metal container filled with coal), Giulio Paolini (with Lo Spazio, eight silhouettes painted white that made up the words “Lo Spazio”), Pino Pascali (with 1 cubic meter of earth, 2 cubic meters of earth, wooden cubes covered with earth), Emilio Prini(Perimeter of Space, neon tubes), Mario Ceroli(Parking, wooden silhouettes), Paolo Icaro(Gabbia, a metal cage painted red), Umberto Bignardi (present with a slide projection), Renato Mambor and Eliseo Mattiacci (present in pairs with a wooden tube installed on the gallery stairs) and Cesare Tacchi (with a leatherette armchair).

The Poverists were inspired by the poor theater of Polish director Jerzy Grotowski: Arte Povera shared with poor theater an interest in simple, ordinary materials, gathered both from nature and from factories, from the industrial world. The theoretical reasons for the group would later be further explicated by Celant in a 1969 text, where the group’s motives become clearer: “Animals, vegetables and minerals have arisen in the world of art. The artist feels attracted by their physical, chemical, biological possibilities, and begins again to feel the turning of things in the world, not only as an animated being but as a producer of magical and marvelous facts. The alchemist artist organizes living and vegetable things into magical facts, works to discover the core, to find them again and exalt them.” For Celant, therefore, the term “poor” is, if anything, to be referred to the language of the group’s artists who, the same critic explained, “eliminate from their research everything that might seem to be mimetic reflection and representation, linguistic habit.” Thus, it is not a matter of reconstructing reality by means of images, but of directly bringing reality (natural or artificial: that is therefore why the materials came from all spheres) into art.

Arte Povera, whose research would later be further developed and deepened with subsequent exhibitions (for example, with the one at the GAM in Turin to 1970) as well as with articles by critics such as Renato Barilli, Carla Lonzi and others, was moving in an international context that had seen conceptual art, Land Art, minimalist art and other forms of expression flourish that moved from theoretical intentions not unlike those that had animated the beginnings of the Arte Povera movement. With Land Art, for example, Arte Povera shared the idea of having the work develop in a natural space and in the landscape(Giuseppe Penone was among the poverists the artist who most insisted on this concept). Soon Arte Povera established itself as a major international art movement (so much so that today it is considered the most important Italian avant-garde of the second half of the twentieth century as well as the last Italian movement to have a strong global relevance), and the works of the poveristi today can be found in major museums around the world. The main merit of the poveristi was to expand the possibilities of artistic practice by opening the work to materials that had never before been considered, and thus to open the work to hitherto unexpressed meanings. Also not to be overlooked is the role that Arte Povera had as a contestation against art forms that were perceived as linked to capitalism (Pop Art for example, of which Arte Povera is the exact opposite: on the one hand the serial work, the work as a product, the work as a consumer good, on the other hand the work as a cultural fact, but also as an ephemeral fact, as a return to nature).

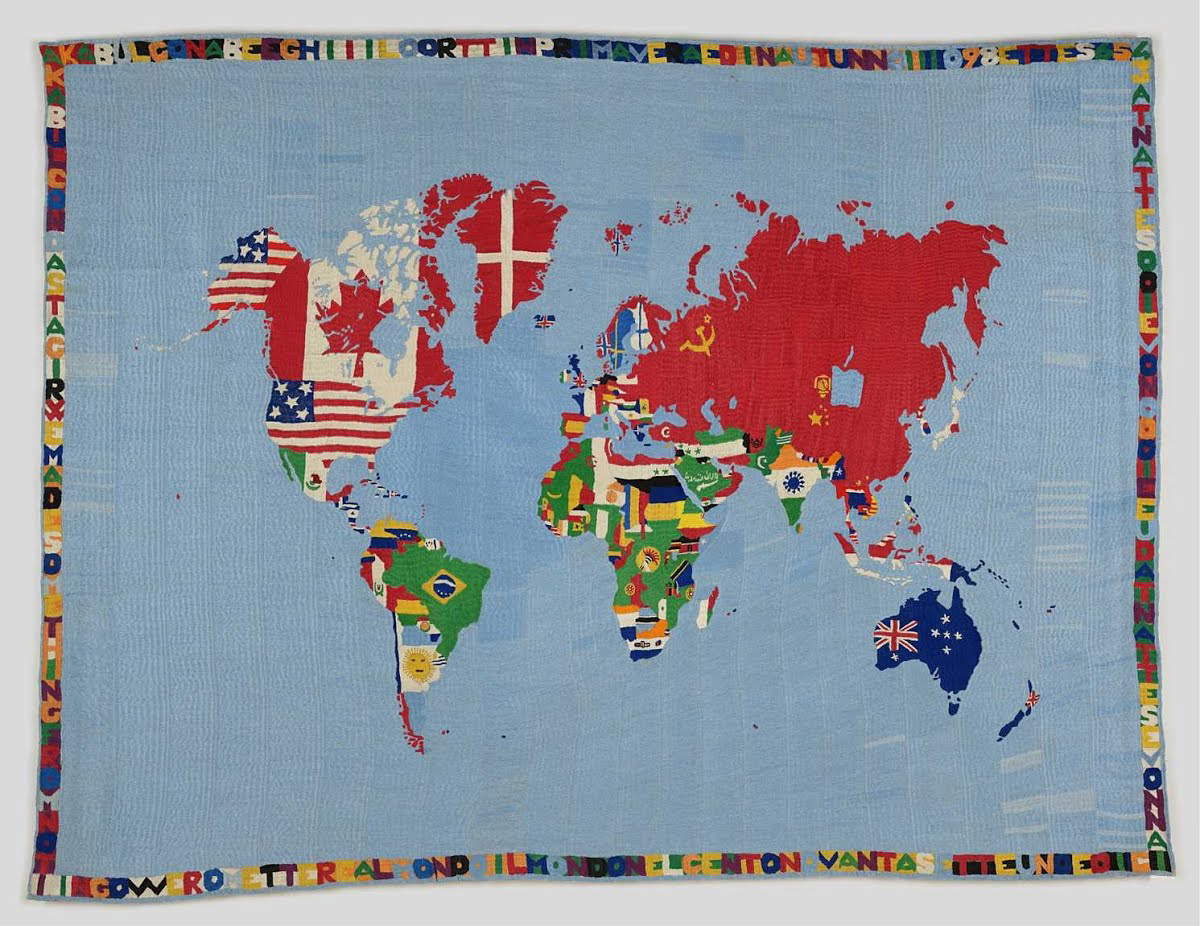

Giulio Paolini ’s (Genoa, 1940) research focuses on language and the very role of the artist, as well as his modes of expression. He is the most conceptual of the poverists and is also the first to have spoken of the “poverty of art.” His practice makes abundant use of photography and quotations taken from the art of the past, as seen in one of his earliest masterpieces, namely the 1967 Young Man Looking at Lorenzo Lotto, a photographic reproduction of a work by Lorenzo Lotto (the Portrait of a Young Man) accompanied by a caption explaining the artist’s attempt to recreate the point occupied by the author in 1505 and by today’s viewer of the painting(read our interview with Giulio Paolini here). Alighiero Boetti (Turin, 1940 - Rome, 1994) works with textile materials and is most famous for his maps, specially made embroidered by Asian (mostly Afghan) weavers where countries are identified by their flags, as well as for his paintings made of colored letters that compose sentences readable each time according to different directions. The maps were Boetti’s way of looking at changes in the world, while the puns were the artist’s invitation, addressed to the viewer, to spur him to think about art and human beings.

Michelangelo Pistoletto ’s (Biella, 1933) goal, on the other hand, is the maximum involvement of the viewer, who in the Mirrors, produced incessantly by the artist from the 1960s to the present, becomes the main protagonist of the work of art (and with him also the whole surrounding environment). Pistoletto is also the author of one of the movement’s symbolic works, the Venus of rags, a provocative installation in which a reproduction of an ancient Venus soars in front of a mountain of rags, as if to symbolize the disagreement between the beauty of art and the chaos of contemporary society. Pino Pascali (Bari, 1935 - Rome, 1968), the most ironic of the poveristas (his “bristle worms” are famous) made surprising compositions resulting from the unusual use of everyday objects. But in Pino Pascali fundamental is also the research on space with large installations capable of occupying even very large spaces (such as 32 square meters of sea about, perhaps his most famous work, a reflection on the conflict between nature and culture and how art sees the elements of nature). Jannis Kounellis (Piraeus, 1936 - Rome, 2017), an artist of Greek origin, is the most “objective” of the poverists, the artist where the boundary between art and reality is most blurred (so much so that his works never have a title, precisely because they are self-evident): famous, for example, is the installation Untitled with which he brought twelve live horses to the L’Attico gallery in Rome in 1969.

The works of Mario Merz (Milan, 1925 - 2003) leverage the theme of growth and development, particularly felt in the 1960s and 1970s. Famous are his Igloos, made with different techniques and materials, which become the symbol of the interaction between human beings and nature and of the transformation of the latter by the former: the igloo, an archetype of the dwelling, is also a metaphor for the relations between inside and outside as well as between individual and collectivity. Marisa Merz (Maria Luisa Truccato; Turin, 1926 - 2019), the only woman of arte povera and wife of Mario Merz, was famous for her works in wool as well as for her “environments,” installations that interacted totally with the space by going to occupy all the rooms in which they were exhibited. Giuseppe Penone (Garessio, 1947) is the poverist who is most connected to nature(read more about his art here), and he usually intervenes with his works directly in the landscape. His works, however, also reproduce the elements of nature, focusing in particular on the processes of growth: this is what happens in Trees, where large tree trunks are reproduced with different materials, nicked and severed by the action of the human being, which, however, fails to affect the structure of the tree, which is therefore returned by the artist to the observer in its essentiality.

Luciano Fabro (Turin, 1936 - Milan, 2007) has gone down in history for his Italie, works with which the artist reproduced the silhouette of the bel paese in different materials with always alienating effects (each time a different material was used) and often charging them with satirical and ideological meanings, as in Italy hanging with a noose upside down. Giovanni Anselmo (Borgofranco d’Ivrea, 1934) is the author of works that explore the theme of energy and the invisible, trying to render these concepts through large installations of objects in relation to each other (with encounters of different elements, balancing, tensions). Emilio Prini (Stresa, 1943 - Rome, 2016), the most elusive and least prolific of the Poverists, but perhaps also the most fundamentalist, was devoted to actions or installations that continually questioned the legitimacy of themselves, employing mediums such as photography, sound, and texts to challenge the sense of perception of the relative and its experiences in matters of art. The works of Pier Paolo Calzolari (Bologna, 1943) bring together elements from the natural world with others that come from the industrial world to make the two worlds interact, often including a dynamic of action and movement in the works as well. Finally, Gilberto Zorio (Andorno Micca, 1944), a sculptor, addresses the theme of the transformation of matter with his works, creating works in constant change.

|

| Arte Povera: origins, birth and style of the movement |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.