Simple, impersonal, silent, even obvious. Yet behind the Untitled title of a great many works of art-most of them, titling being a fairly recent invention-flies the banner of a quest that has proudly set itself free from the dominance of words, from the yoke of literature. With legions of painters who have renounced titling their individual works in the name of art for art’s sake. And because of a desire to offer the public a work open to possible, other people’s interpretations. In these present years of programmed planning of the artistic product, of the dominance of content (preferably committed content) over form, of the side-by-side (when not overlapping) of marketing and communication experts with the figure of the artist, pushed and/or forced to brand his or her work for the purpose of its commodity identification, the aseptic and ascetic practice of those - and there were many - in the twentieth century who titled with a non-title what came out of the atelier may sound like a jarring. To this battle of the image against the word that synthesizes and cages it, is that engaged painters such as Mirò and Picasso, but above all the protagonists of the so-called New York School, then the authors of the Arte Povera epic (1967-1971), is dedicated Chiara Ianeselli’s book Sulla necessità del Senza titolo. Silence as the Language of Art (Postmedia, 2025, 133 pages, 16 euros).

The young art historian and curator from Trentino, currently engaged with a position at the Maxxi in Rome, has given to the press the gist, and the best, of her doctoral thesis (of which she also maintains didactic setting and outline) dedicated to titles in works of art. Let us say at once that her book stands out for its vast bibliography, rich above all in quotations from American non-fiction, to which she has added unpublished testimonies gathered in dialogue with the survivors of that season, in many ways, deliberately “aphonic” (interviews with the poverists Anselmo, Paolini, Piacentino, Penone), supplanted in the 1980s of the return to painting (Transavanguardia, Pittura colta, anachronists) by the revival of learned and literary citation in titles.

Yet for centuries, the work of art did without the title. It was the subject, whether it was a painting made for a religious or secular commission, that defined the individual piece. And the generality or universality of the theme (Madonna and Child with Saints) was made up for, for the purpose of identification, by a meticulous description. One need only refer back to Lorenzo Lotto’s Account Book, which, on February 10, 1545, noted the receipt of 16 ducats as payment received for the intense Vesperbild, now in the Brera Pinacoteca, which the Venetian painter defined exactly (but not succinctly) “pictura de una paleta [...] fatta per una pietà, la Vergine tramortita in brazo de San Joanne et Jesu Cristo morto nel gremio de la matre, et due anzeleti da capo e piedi sustentar el nostro signore...” Certainly, on the other hand, Perugino’s populous and mythical painting now in the Louvre has its own title, Combattimento tra Amore e Castità (Combat between Love and Chastity), this thanks to the fact that Isabelle d’Este, in her 1503 contract with the painter for the work to be placed in her Mantuan Studiolo, asks, that is, has Vannucci ask, “una batagla (sic.) of Chastity against di Lascivia, that is, Pallas and Diana fighting manfully against Venus and Love.” But a few years later Giorgione put his hand, before his death in 1510, to his probably most famous painting without leaving a signature or title: The Tempest, as Marcantonio Michiel called many years later, in 1530, the “little village” of “Zorzi de Castelfranco” seen in Gabriele Vendramin’s house, and as we admire it today at the Gallerie dell’Accademia in Venice.

The emergence of collecting and the related need to compile inventories of collections have, especially in the 19th and 20th centuries, under the impetus of merchants interested in having easily identifiable and marketable products, caused titles and literature to flourish around the discourse for (only) pictures of painters. Titles thus became, under the impetus of Symbolism and then Surrealism, but also Futurism, i.e., the movements with greater literary implication, “a real name that the work carries with it,” Ianeselli notes in his opening remarks, “and that often determines the identity and understanding of what is represented. Often even inscribed, sometimes engraved by the artist himself or inserted in the captions, the titles accompany the work as true baptismal certificates.” What else to call De Chirico’s painting in the Mattioli collection (Museo del Novecento) in Milan L’enigme dell’heure if not L’enigme dell’heure, given that the pictor optimus titled it so, leaving it imprinted on the frame of his metaphysical masterpiece?

Yet already in the nineteenth century there were those who rebelled against the domination of the word, the univocal epitome. Ianeselli, in a lengthy note on page 36, reports the annoyance expressed by James Wistler at the fact that to his musical Arrangement in Gray an Black, sent in 1872 to the Academy, the catalog’s drafters had expanded the artist’s original title with the addition: Portrait of the Mother of the Painter. “But what can or should the public care about the identity of the portrait?” the great English painter wondered about this, adding, “As music is the poetry of sound, so painting is the poetry of sight, and the subject has nothing to do with the harmony of sound and color.” Pressing for a name that would make the work unique and easily identifiable and marketable were and are, however, gallery owners and dealers. For example, in Picasso’s case, the legendary Kahnweiler and Vollard, with the consequent but belated rebellion of the Malagueño, who in 1946 declared that he would not name his works, lashing out “at the mania of art dealers” and “critics,” as well as “collectors, to christen paintings.”

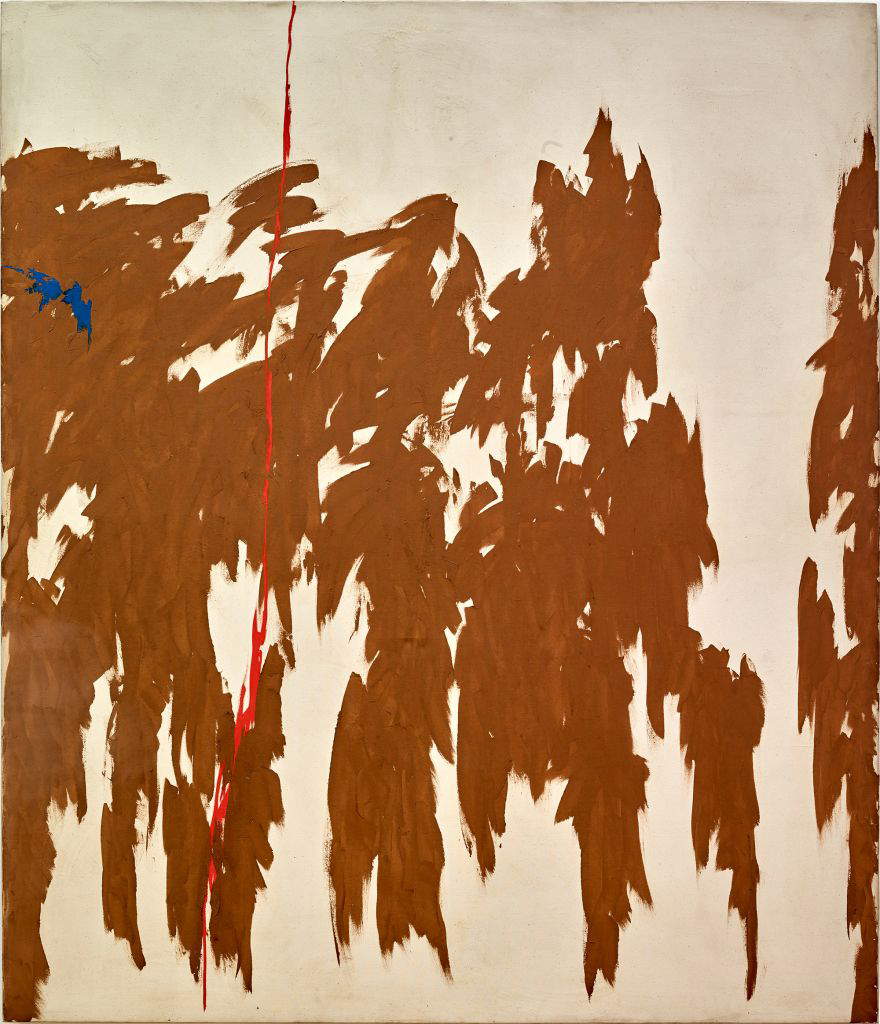

Rich in quotations from the protagonists, and enjoyable even by a lay audience, Ianeselli’s book focuses, in articulating and arguing the discourse On the Necessity of the Untitled, on Abstract Expressionism and Minimalism made in the U.S., then on Italian Arte Povera. The most drastic and furious in defending his own paintings that “remain nameless, as they should,” since they “are not about life” but “lead a life of their own,” appears, among the American Abstract Expressionists, Clyfford Still. Having been saddled by Peggy Guggenheim with titles such as Buried Sun and The Comedy of Tragic Deformation to paintings exhibited and for sale in 1946 at the Art of This Century gallery, Still from 1959 removed all titles not his own from old works and stopped naming new ones except through a system of letters and numbers to make them recognizable. The number was, after all, the system used by, among others, William Baziotes, Jackson Polloick and Mark Rothko who, beginning in 1948, began titling his paintings Untitled (nearly 150 of his works with this definition, his son Christopher noted disconsolately as he grappled with his father’s archive) to add in the following decade, beginning in 1955, the colors present in the painting.

An Ad Reinhardt’s Art for Art’s sake versus art as commodity brought with it the fundamentalist choice of American Minimalism. With Donald Judd, a critic before a sculptor (a qualification, however, stubbornly rejected by him), who, a proponent of a production disconnected from any reference to the real world, in Complaints: Part I declared, “I prefer art that is not associated with anything,” going so far as to ironically rename his Untitled works with simple definitions like The Bleaches: more than titles, nicknames. And in the same vein Robert Ryman who declared, "I do not abstract from anything [...] I do not work on a representational basis [...] No symbolism. No illusionism,“ going so far as to amuse himself by naming his paintings after the brands of colors employed. ”When Ryman’s exhibition,“ Ianeselli notes, ”was titled No Title Required, the disdain for titles reached a critical point.

The untitled with which Francesco Stocchi (not) entitled the section he curated, but by the artists interpreted, at the 18th Quadriennale d’arte nazionale di Roma currently underway at the Palazzo delle Esposizioni, has in short a long history behind it. Which also passes through the Arte Povera experience of Germano Celant and artists such as Giovanni Anselmo and Jannis Kounellis who systematically used the Untitled - italicized, because given by theauthor and to be distinguished from the very definition employed by curators and extenders in front of unnamed works-while Alighero Boetti relied, among other things, on tautology by listing materials(Pietre e plate di metallo, 1968). Where, however, a doc poverist like Giuseppe Penone titled his sculptures instead: “I have continued to use the title to orient the reading of the work,” the artist told Chiara Ianeselli in 2020, "and to clarify that the work is not only a formal research but there is a thought, an idea that is identified through the title, such as Respirare l’ombra." In 1969 in Arte povera, Germano Celant, the theorist and soul of this trend in Italian art, had instead been clear about the poetics of the Arte povera artist, the ideal poverista: “His works are often untitled, almost as if he wanted to establish a physical-mnemonic certificate of the experiment, and not an analysis or subsequent development of an experience.” After all, Celant’s neo-avant-garde paladins did not always share, see Pistoletto, the trademark. And so the bare, raw things of earth and industry still found an evocative name that made them mysterious, mythical, memorable.

The author of this article: Carlo Alberto Bucci

Nato a Roma nel 1962, Carlo Alberto Bucci si è laureato nel 1989 alla Sapienza con Augusto Gentili. Dalla tesi, dedicata all’opera di “Bartolomeo Montagna per la chiesa di San Bartolomeo a Vicenza”, sono stati estratti i saggi sulla “Pala Porto” e sulla “Presentazione al Tempio”, pubblicati da “Venezia ‘500”, rispettivamente, nel 1991 e nel 1993. È stato redattore a contratto del Dizionario biografico degli italiani dell’Istituto dell’Enciclopedia italiana, per il quale ha redatto alcune voci occupandosi dell’assegnazione e della revisione di quelle degli artisti. Ha lavorato alla schedatura dell’opera di Francesco Di Cocco con Enrico Crispolti, accanto al quale ha lavorato, tra l’altro, alla grande antologica romana del 1992 su Enrico Prampolini. Nel 2000 è stato assunto come redattore del sito Kataweb Arte, diretto da Paolo Vagheggi, quindi nel 2002 è passato al quotidiano La Repubblica dove è rimasto fino al 2024 lavorando per l’Ufficio centrale, per la Cronaca di Roma e per quella nazionale con la qualifica di capo servizio. Ha scritto numerosi articoli e recensioni per gli inserti “Robinson” e “il Venerdì” del quotidiano fondato da Eugenio Scalfari. Si occupa di critica e di divulgazione dell’arte, in particolare moderna e contemporanea (nella foto del 2024 di Dino Ignani è stato ritratto davanti a un dipinto di Giuseppe Modica).Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.