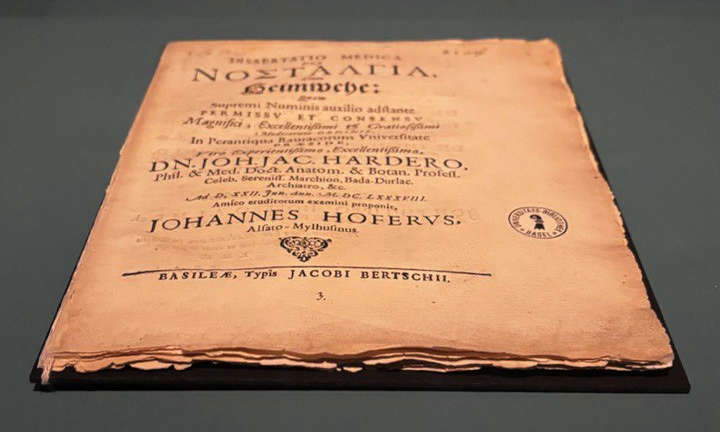

It is the fault of a young man who studied medicine in late 17th-century Switzerland that today we are accustomed to taking on, whether we like it or not, increasingly large doses of nostalgia. He was the first to pose the problem of codifying this feeling. Johannes Hofer, nineteen years old, graduated in medicine from Basel in 1688 with a thesis on a strange disease he had studied about Swiss mercenaries sent to fight far from home. What he then did throughout his career, Dr. Hofer, virtually no one knows. His name is linked to that thesis, to that paper in which the boy invented nostalgia. Literally: it was he who coined the term, given in large Greek letters on the cover of his dissertatio printed in Jacob Bertsch’s printing house. It was an almost literal cast of the German Heimweh, which already existed. That German term so whiny, so unpersuasive, which until then had been used at most by a few plaintive valley dwellers far from home, and which Hofer had had imprinted in Gothic characters under the new expression, was putting on a new dress to take on an unprecedented universal connotation, as well as a scientific significance. And so nostalgia was born. Between the pages of a dissertation four centuries ago. At the time it was considered a disease that needed treatment, because if in 1688 you were a Swiss mercenary who instead of fighting was thinking about distant mountains and valleys and who knows if he would ever see them again, then you were a problem. In fact, a big problem: homesickness meant fighting without motivation, fighting without motivation meant the risk of desertion. And for the captains who were supplying Helvetic mercenaries to the French, desertion meant loss of money, because they were losing out on their own, since the task of arming the soldiers was not the responsibility of the patron. The need to find a cure for that disease was therefore quite felt.

This is the starting point for the exhibition that Palazzo Ducale in Genoa is dedicating to nostalgia. The cover of Johannes Hofer’s thesis placed in the entrance hallway is a kind of portal, the start of a journey through time through centuries of longings, torments, departures, returns, sighs, fervors, personal struggles, collective invasions. Proving that nostalgia has always been there, has always existed, has often guided our actions. There is no person in the world who has not felt a sense of nostalgia at least once, Eugenio Borgna recently wrote. “Nostalgia, and nostalgia wounded by the passage of time, in particular, which dilates it and makes it ever more acerbic and painful, ever more fragile and arcane, is interwoven with memories, which have to do with the past, and not with the future, with a past that is bright and shimmering, or instead dark and lacerating, and which are born and die like fragile and ephemeral butterflies, ethereal and elusive.” Everyone has a past in which to swim for a few surface strokes or into which to dive for deep, long, troubled explorations. That is why it is not just a “modern” feeling, as the title of the review reminds us(Nostalgia. Modernity of a Feeling from the Renaissance to the Contemporary, curated by Matteo Fochessati in collaboration with Anna Vyazemtseva). It is a feeling that is always present in all eras, and ours is no exception; it is one of the most vivid, most felt feelings, indeed it is something more: it is a complex of feelings, it is an intricate set of emotions that transcend spaces, times, dimensions of every order and size, a set that can lead to paralysis or action, retreat or revolution.

Those who think that nostalgia is an obsolete feeling are perhaps living in a dimension that has never known Johannes Hofer, that has never wondered about that feeling that we like so much because it is sweet and bitter at the same time. So much so that it even becomes a product. Those who think that society today is too fast, too used to the rapidity of change that technological evolution imposes on us, too busy chasing a present that slips on its Instagram feed to waste time behind pining for a past that is impossible to unearth, perhaps should, let’s put it this way, go at least once in their lives to Versilia. Preferably on a summer weekend. And possibly in the company of a friend who works in a communications agency. The friend will say that probably all Versilia nightclub managers have been in school from the American publicists and economists who in the late 1980s started talking about nostalgia marketing. Someone, at that time, must have realized that a consumer’s choices can be heavily influenced by a communication that leverages elements capable of reminding him of the dear departed past, of recalling the culminating, most exciting and enjoyable moment of his own existence, usually placeable around the age of twenty to twenty-five, and consequently that nostalgia is a product with infinite sales potential. Versilia has for years been a perfect ground for the application of nostalgia marketing. Fabio Genovesi wrote that nostalgia is the typical product of Forte dei Marmi: “the ideal business, since the raw material is provided by the consumers themselves, men and women who come to buy back their lost summers.” Here it is everywhere then, nostalgia. In the discos of Versilia. In the TV shows that on Saturday nights evoke the glories of the sixties-seventies-eighties-nineties, and to each viewer his or her golden years. In the advertisements we swallow in a continuous stream by every possible means, cars, movies, TV series, shoes, sunglasses, stylish clothing, technical clothing, sportswear, washing machines, cameras, soft drinks, video games, sandwiches, low-cost furniture, watches, soaps, detergents, pasta, sauces, snacks, music. In the slogans with which campaign leaders anesthetize the critical sense of the masses who follow them and vote for them because once stuff was cheaper, once there ’was jobs for everyone, once politicians stole for others and not for themselves, once there was no euro, once there was no globalization, once there was no this, once there was that, once there was no that. But why are we so attached to what once was? In Genoa, an attempt is made to investigate the issue, with a preamble that does not start from the Renaissance, as the title would suggest, but from much earlier.

Twenty-five centuries before Hofer, Homer sang of the suffering of a hero, Ulysses, who wanted no more of wars, battles and various messes and only wanted to return to his home, to his wife, to his child, to his little island in the middle of the Ionian Sea, but the cynical and adverse gods would not let him. Nostalgia is literally the “pain of return.” And so the personification of theOdyssey painted by Ingres encapsulates, in that sad, cogitabond figure, caught tearing over a gloomy background, all the meaning of Odysseus’ torments: nostalgia is the desire to return to spend what he has left to live there where there is still some fragment of his past, a past that motivates him, impels him to overcome sorceresses and monsters and vengeful gods in order to return to where his affections, his pasts, his memories are kept. He is the exact opposite of Aeneas, the other hero of antiquity whom the exhibition places at the opening of the itinerary to immediately confront the audience with the two paths one can take in the face of nostalgia. Odysseus wanted to regain what he had lost. Aeneas was aware that what he had lost could not return, because it was burning behind him: in Pompeo Batoni’s painting in the Royal Museums of Turin, his city is already scorched by flames, as per the iconographic topos . And so there is nothing left to do but to load on our shoulders the little we manage to save (and that fortunately coincides with family members, at most the statuettes of the lari, to remind ourselves that wherever we go there will still be our home with us) and go to meet another fate.

A fate that is not so different from that of so many exiles listed by the review in the following room: a Dante Alighieri stopping in front of the Entella, in a piece of Ligurian landscape painted by Tammar Luxoro, the celebrated Foscolo painted by François-Xavier Fabre, the generic exile from Italy by Andrea Gastaldi. Nostalgia for home then, but also awareness of something that no longer exists: the same awareness that moved a proactive Byron (ancient Greece is no more, but that is still no reason not to help the Greeks free themselves from Ottoman oppression), and Piranesi to become probably the first nostalgia marketing expert in history, since his views of ancient Rome depopulated among Grand Tour travelers (although some, like Goethe, were disappointed uponarrival in Italy, because in person they could not encounter the sense of magnificent, nostalgic grandeur in ruins that Piranesi’s etchings had been able to inspire when they began planning their descent beneath the Alps). The curators seem to want to tell us that nostalgia can be active and passive, in short. And immediately afterwards they tell us, in a somewhat interlocutory room, that the most suitable sensation to accompany nostalgia may just be melancholy: one room explores, somewhat hastily, this theme, another subject so vast that it has already had its own dedicated exhibition, at the Mart in Rovereto, last year, built in part around Dürer’s Melancholia I , which is also on display in Genoa. The Dürer burin is, moreover, one of the two reasons that prompt the visitor to linger inside this room before following along the path: the other motif is the Specchio d’acqua (Mirror of Water ) by Sexto Canegallo, a recently much reappraised Genoese painter who worked his own very particular synthesis of symbolism and divisionism to arrive at original results such as the one on display, an elegy where all of nature seems to weep along with the three figures seated, mournful and grieving, on the shore of a lake (for one knows, every melancholic must by contract look at a body of water).

The first rooms, then, have the function of introducing the rest of the tour, which is all, to the end, one long catalog of different forms of nostalgia. Not exhaustive, of course, because there are too many guises that this complex of emotions, the most protean of all, can take on. It begins with Nostalgia of Home , which contains some of the exhibition’s highest and most moving points: the goodbyes of emigrants leaving early 20th-century Italy on the ships that loaded them and took them to America resonate in a famous and touching painting by Raffaello Gambogi, perhaps the most poetic on the theme of Italian emigration at the time, and find their natural echo in Adrian Paci’s Migrants of the Temporary Residence Center , the well-known performance of theItalian-Albanian artist during which a group of migrants remains suspended above the moving ladder of an airplane in the middle of a landing strip, an allegory of the anguished uncertainty in which all those in their condition are often forced to grope. The panels in the room evoke Umberto Boccioni’s States of Mind , one of the most moving works in the history of art, unfortunately not present in the exhibition: there is, however, a painting that somehow takes its place, Luigi Selvatico’s Morning Departure , another work that cannot fail to touch deeply anyone who, in his or her life, has at least once been forced to say goodbye to a person. Maybe in a train station. Maybe in the cruel knowledge that that person, once on that train, would be gone forever. And then one indulges in sadness, like the woman in Selvatico’s painting, left alone to wipe away her tears as an annoying winter fog creeps across the platforms of the Venice train station. Nostalgia is not only of those who leave, it is also of those who stay.

Having passed, at least for the moment, the deep abysses of intimate and personal nostalgia, one enters the swamps of collective and political nostalgia, to which much of the exhibition is devoted. And the first form of collective nostalgia is that of paradise, the sigh for a lost golden age, the era of primordial bliss that is gone, over, buried under the blankets of disillusionment, technology, and progress: it is well known that the longing for an age when human beings were in perfect harmony with nature (assuming that this age ever existed) is another motif that transcends the ages and on display inspires, beyond the various depictions of paradise (Jan Bruegel the Younger’s, overflowing with angry black animals, is tasty: they evidently already felt that the appearance of man on Earth was not to be a good deal), some country scenes by a Felice Carena or a Gisberto Ceracchini for whom paradise is, quite clearly, a meadow where they can rest with a few naked women bathing, country concert style à la Titian and followers (Manet included) or, for the good father of the family, a countryside where he can sprawl out with wife and children in tow, indulging at most in a few languid glances at the first passing sheep, who knows whether in the memory of the primordial ages of a Piero di Cosimo where men and animals lived in harmony to the point of sharing everything, everything, but really everything. Some creaking can be heard in the next room, devoted to the nostalgia of the classic, where the theme is resolved in the most classic of ways: references to Grand Tour travelers with souvenirs d’Italie by ordinance( Giovanni Faure’sThe Roman Forum , a typical ’tourist’ view of the 19th century, we might say, or Michele Marieschi’s Capriccio con ro vine, a talented vedutista accustomed to working for the herds of foreigners who invaded his Venice as early as the 18th century), but also with a few paintings with a moremore meditative accent (Federico Cortese’s spectacular and disturbing ruins, or Émile-René Ménard’s sinister temple of Segesta), and then the ever-present rappel à l’ordre, the classicism of the 1920s, which here takes the form of De Chirico’s mythological figures or De Pisis’ archaeologist. Absent, on the other hand, is any reference to Renaissance classicism, not least because the reforming intentions of the intellectual class of the fifteenth century did not start from a sense of suffering in regard to the past, but if anything from a new sensitivity to the ancient, from new stimuli, from an awareness of the temporal gap between the present and the past, with the consequent load of transformations that the classics have undergone in the intervening period of time (“The myth of the ancient and its invocation precede the imitation of the ancient,” Eugenio Garin wrote, and “the decision of a renewal is not the consequence but the premise of the actual, broad and choral rebirth of classicism.”)

If, however, the assumption of a gaze that does not exude nostalgia (or, at least, not in the forms that this gaze would have taken from the eighteenth century onward) holds true for Renaissance classicism, it should in part also hold true for the classicism used to construct theimage of the Fascist regime, if one admits that Fascism retained traits of that “modernist nationalism,” according to Emilio Gentile’s definition, which was typical of the avant-garde intellectual movements of early 20th century Italy: “historical tradition, for fascism, was not a temple where to contemplate and nostalgically venerate the greatness of remote glories, preserving intact the memory consecrated by archaeological vestiges: history was an arsenal from which to draw myths of mobilization and legitimization of political action” (so Gentile himself), and consequently “fascism had no nostalgia for a realm of the past to be reconstituted, it did not establish the cult of tradition as a sublimation of the past in a metaphysical vision of intangible order, to be preserved intact, segregating it from the accelerated pace of modern life.” For Mussolini, the past was, in his words, a “fighting platform for going forward into the future.” It was not the memory of a golden age to be re-enacted, or at least not in the most common meaning, that of re-enactment as an attempt to search for a simulacrum of the past that must then be preserved from the frenzied and slaughtering rhythms of modern society. The idea, presented in the panels of the rooms in the exhibition, that the programs of the dictatorships of the twentieth century envisaged a kind of ideological reaction to the idea of progress, since progress would be seen as a threat to the cornerstones of tradition, risks being too hasty and indulging in overgeneralization. Fascism harbored no ideological aversion to progress. However, in the exhibition the public will find a vast congerie of paintings depicting the peasants who were supposed to be the guardians of tradition to whom the Duce’s message was addressed (verbatim: in the tour itinerary there is also a sketch by Luciano Ricchetti for a painting that won at the first edition of the Cremona Prize, in 1939, and that depicted a family of peasants gathered to listen to Mussolini on the radio), and who were certainly exalted by Fascist propaganda, but were not, however, at odds with the modernizing ideology of the regime. The Nazi regime, on the other hand, is a different matter, evoked in the exhibition by some paintings by Ivo Saliger, exhibited above all to give an account of how Nazism had misrepresented Winckelmannian aesthetics in the name of an improbable Aryan ideal of beauty that was among the motives capable of inspiring the nefarious, gloomy consequences that we all know.

After a coda shot with a room devoted to nostalgia for the ancient, we move toward the exhibition finale with a certainly better part, with more intimate tones: we begin with the “nostalgia of elsewhere,” the longing for faraway and unknown places that in the itinerary is expressed through paintings that dream of distant lands or revive the memory of them, such as Domenico Morelli’s Pompeian Bath , which blends Orientalist suggestions with archaeological interests, or like Galileo Chini’s celebrated Ora nostalgica sul Me Nam (nostalgia squared, in short), one of his most famous paintings from the Siam period (the two years in which he was called to work at the court of King Rama VI), the same land where Carlo Cesare Ferro Milone stayed, also present with one of his paintings. Then there is a passage on the “Looks of Nostalgia,” a small parade of female figures (who knows why only women: perhaps a counterbalance to the two male nostalgists with whom the path opened) caught in a pensive attitude: it is an opportunity to see a couple of first-rate pieces such as Amedeo Bocchi’s Fior di loto or Pompeo Mariani’s L’ innamorata del mare , works in which melancholic intonation and symbolic references weave a dense sentimental fabric that captures the visitor and prepares the way for the last rooms, which are among the exhibition’s highest moments. The curators, in the finale, want to strike at the audience’s heart by exhuming childhood memories: the Nostalgia of Happiness, in the last room before the Doge’s Chapel (and thus in the Doge’s Apartment’s most collected room) is a set of paintings that try to evoke the larvae of joy, of the cheerfulness of when one was a child or teenager: it happens in Glenn O. Coleman, a backlit view of an open-air cinema and its audience; in Ettore Tito’s Spiaggia del lido , one of the Venetian painter’s many paintings on the theme of carefree days at the seaside; and especially in Giacomo Balla’s Luna Park Parigi , one of the works worth visiting the exhibition for, a night view of an amusement park vaguely blurred by the fog of memory, the lights of the rides in the background brightening the night, the couples that crowd in front of the attractions, acrowding in front of the attractions, an indistinct mass with unrecognizable faces, suspended between dream and memory, rising from below like a cloud of ghosts returning from a happy past, to shake for a moment a present that no longer has anything to do with anything in the painting, with the lights, with the rides, with happiness. The closing, then, is a small sampling of the responses that artists from the second half of the twentieth century onward have given to the nostalgia of the infinite: the thesis of the exhibition is that nostalgia, in the modern sense, is both sensation and awareness of a permanent loss, mixed with a sense of “estrangement from the sense of the absolute of the universe.” In contemporary art, on the contrary, there is a continuous tension toward this infinity, a continuous attempt to connect with this dimension, which is expressed through a great variety of research: Anish Kapoor’s sculptures (one of the rare respectful interventions in the Doge’s Chapel seen in recent years) are surprising for their ability to challenge the perception of the relative, one goes beyond time and space with Lucio Fontana’s cuts, and one ends up losing oneself in Ettore Spalletti’s infinite blue.

They are among the few sharps of a little contemporary in an exhibition from which one might have expected a more thorough examination of current languages, even if that little contemporary marks some of the most intense moments of an eventful review, which wanders from era to era, between one revival and another, to return a compendium of the contemporary art of the past.other, to return a compendium of the various forms of nostalgia to an audience increasingly accustomed, perhaps unwittingly, to feeding on this sentiment, an audience increasingly induced to dream on simulacra, increasingly forced to drink the ersatz of a sentimental entanglement that once moved the pens of poets and today moves the notebooks of copywriters in search of ideas to sell ice cream. Restoring dignity to one of the noblest sentiments: this is what the works hanging on the walls seem to say.

Articulate, long, cultured, full of references, at times even poignant, the exhibition on nostalgia at the Doge’s Palace has the density of a book, the pace of a film, the fragrance of a journey, with peaks of vivid intensity alternating with slower and perhaps even a bit boring moments, pauses, takes, immersions to end with a kind of revelation that widens the gaze to a dimension that is no longer even earthly. It is because nostalgia does not have an earthly dimension: an unknown visitor must have been well aware of this, who, on one of the post-it notes that are distributed at the bookshop to leave his own thoughts on the subject stuck to a wall, wrote that nostalgia is the scent of eternity. Perhaps Borges must have also thought something similar when he wrote that remembrance tends toward timelessness: “we enclose the happinesses of a past in a single image; the variously red sunsets that I admire every evening will be the memory of a single sunset. The same happens with foresight: the most incompatible hopes can coexist undisturbed. In other words: the style of desire is eternity.” Nostalgia is probably something similar. A feeling that binds all memories together, all hopes together, past, present and maybe even future together, in the golden blurred light of a time that never ends.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.