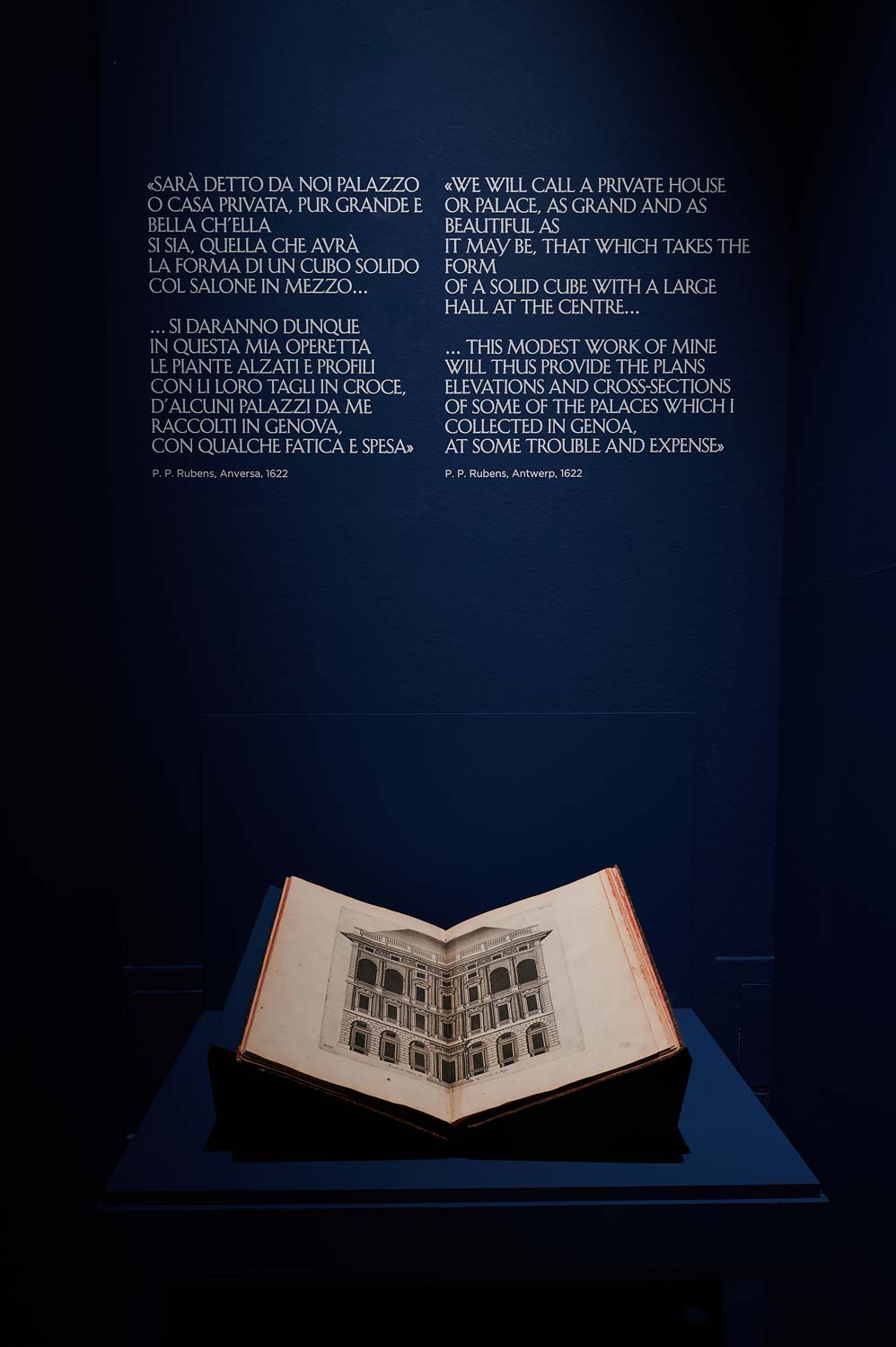

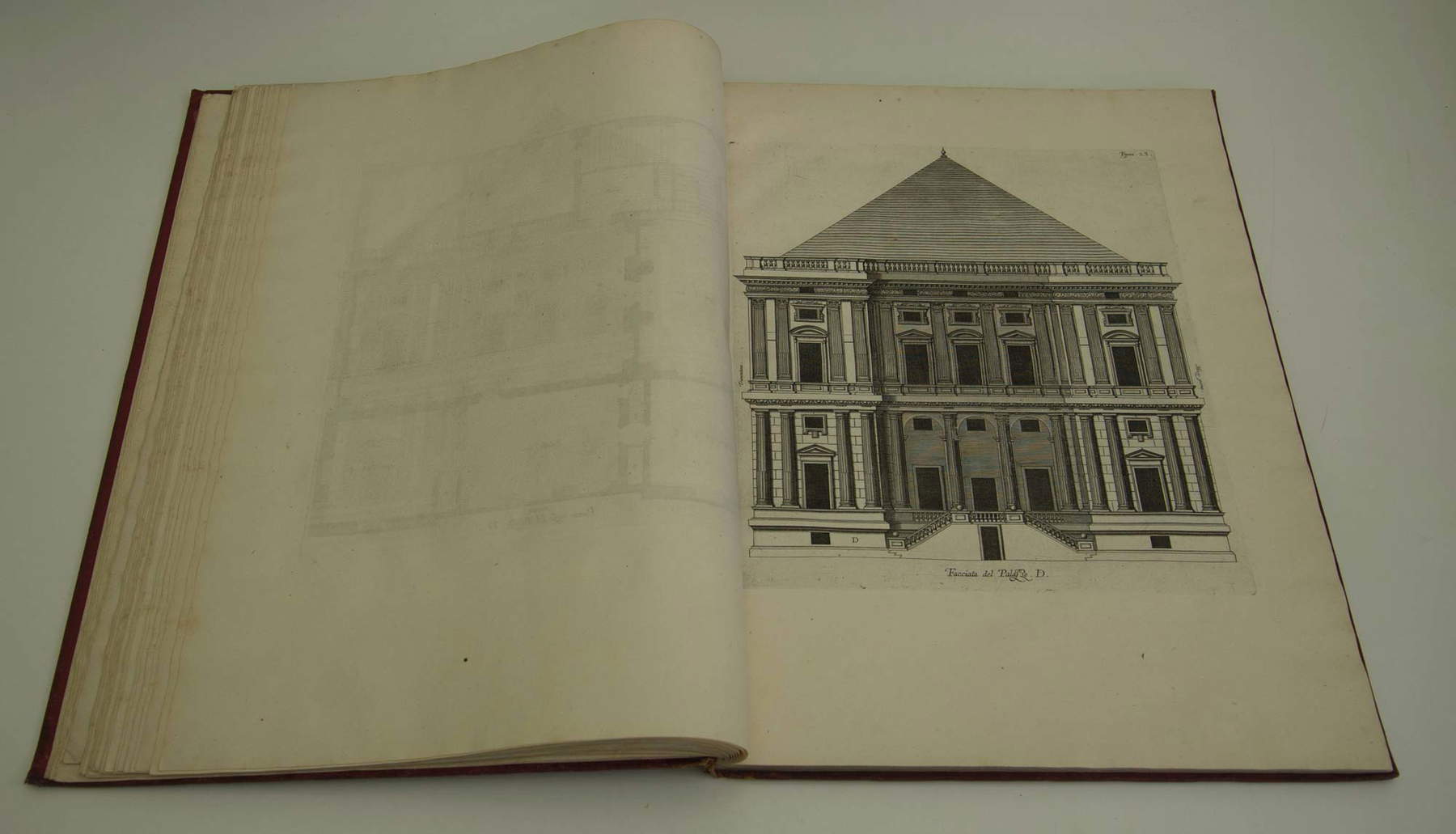

Exactly four hundred years have passed since the publication of Pieter Paul Rubens’s Palazzi di Genova, the book with which the great Flemish artist, moved by a keen interest in Genoese architecture, so much so that he gave the volume to the presses at his own expense, dedicated to the buildings in which the city’s patriciate resided. Rubens’s book represents one of the most relevant documents on the Genoese culture of living, the taste of the early part of the 17th century, the choices of the seventeenth-century nobility, as well as an insight into the economic, political and social situation of Genoa at the time. So, Genoa is celebrating the anniversary with a long exhibition between the rooms of the Palazzo Ducale, Rubens in Genoa, curated by Nils Büttner and Anna Orlando, dedicated, as the presentation states, “to Pietro Paolo Rubens and his relationship with the city.” This is not an unprecedented operation: the exhibition, which can be visited until February 5, 2023, was in fact preceded by two other significant exhibitions, both held at Palazzo Ducale, which explored the same topic.

A pioneering role must be ascribed to the exhibition Rubens and Genoa of 1977-1978: organized a few years after the economic crisis of 1973 and the consequent austerity (in the introductions of the catalog one can grasp the reflections of a period of economic straits that prevented the realization of a major exhibition), as part of the “international year of Rubens” that commemorated the fourth centenary of the artist’s birth, it was the first exhibition in which the ties between Rubens and Genoa were reconnected in a systematic way. An exhibition, declared curator Giuliano Frabetti (who worked with a committee composed, in addition to himself, of Giuliana Biavati, Ida Maria Botto, Giorgio Doria, Ennio Poleggi and Laura Tagliaferro), "centered above all on aspects of the Genoese way of life at the time of Rubens, seen from the perspective of the culture, humanity, and art of the Flemish, which scrutinizes them, understands them, illustrates them, and compares them internationally." The review consisted of an initial introductory historical-economic section, followed by a chapter on Rubens’ relations with the city, a section on the Palaces of Genoa, and a focus on the painter’s Genoese paintings. The public, Frabetti wrote again, should not “expect from the exhibition the triumphalist parades of masterpieces” that had animated the various European exhibitions of the Rubensian year, from Antwerp to Vienna via Florence, because of a series of “practical and economic limitations” that had forced the curators to a “meager sampling.” Scanty, to be sure, but a decidedly significant basis for setting up the work: thus arrived at the Ducal Palace theHercules and Deianira from Turin (then at Palazzo Madama, now at the Galleria Sabauda), the Portrait of Ladislaus of Poland and the Portrait of Philip IV from the Durazzo Pallavicini collection, the Equestrian Portrait of Giovanni Carlo Doria (a painting at that time not yet resolved with certainty, although the curators inclined to identify the effigy as Giovanni Carlo Doria, an identification no longer in dispute today: the painting had been tracked down by Longhi in 1939 and was kept in the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence), and the two altarpieces from the Gesù church (the Circumcision and the Miracles of St. Ignatius) were listed as integral parts of the exhibition, although they had not left their locations. The selection concluded with a portrait of Vincenzo I Gonzaga, from the Rizzi Gallery in Sestri Levante, given to Rubens, but which the curators assigned instead to Frans Pourbus the Younger, an attribution later not disputed.

A completely different atmosphere accompanied the major exhibition L’età di Rubens, curated by Piero Boccardo, with the collaboration of Clario Di Fabio, Anna Orlando and Farida Simonetti, and organized in 2004 as part of the initiatives for Genoa European Capital of Culture, in the last remnants of a long period of economic prosperity that the subprime crisis would interrupt three years later. A time when it was customary to see exhibitions of enormous scope, such as was, indeed, The Age of Rubens, which, as per its title, did not focus exclusively on the relationship between artist and city (as much as there were several paintings in the exhibition that support Büttner and Orlando’s review today: the portrait of Buscot Park, the portrait of Giulio Pallavicino, the Turin paintings, and the Lamentation of Venus on Adonis, exhibited then as an original and now demoted to a copy although the question is still open, and then again the portrait of Geronima Spinola Spinola with her granddaughter, to which were added the Brigida Spinola Doria from the National Gallery in Washington, the Giovanni Carlo Doria from Palazzo Spinola, the Juno of Cologne, the Bronze Serpent from the National Gallery, the Giovanna Spinola Pavese from a private collection), but more broadly on collecting in Genoa at the time: the result was not only a systematic yet wide-ranging exhibition, with Rubens’s works placed within a parade of masterpieces (by Caravaggio, Titian, Guido Reni, Paris Bordon, Orazio Gentileschi, Antoon van Dyck, and numerous other artists) that offered with explosive effectiveness an eloquent picture of the collectors’ picture galleries of the time, but also an accompanying publication that stood somewhere between the exhibition catalog and the catalog raisonné, with the entire registry of Rubens’s “Genoese” works (either executed for Ligurian clients or arrived in the city due to collecting vicissitudes, and then again those untraceable and those once given to Rubens but then expunged from his catalog), and in-depth features on individual collectors, complete with reconstruction of the inventories of their collections.

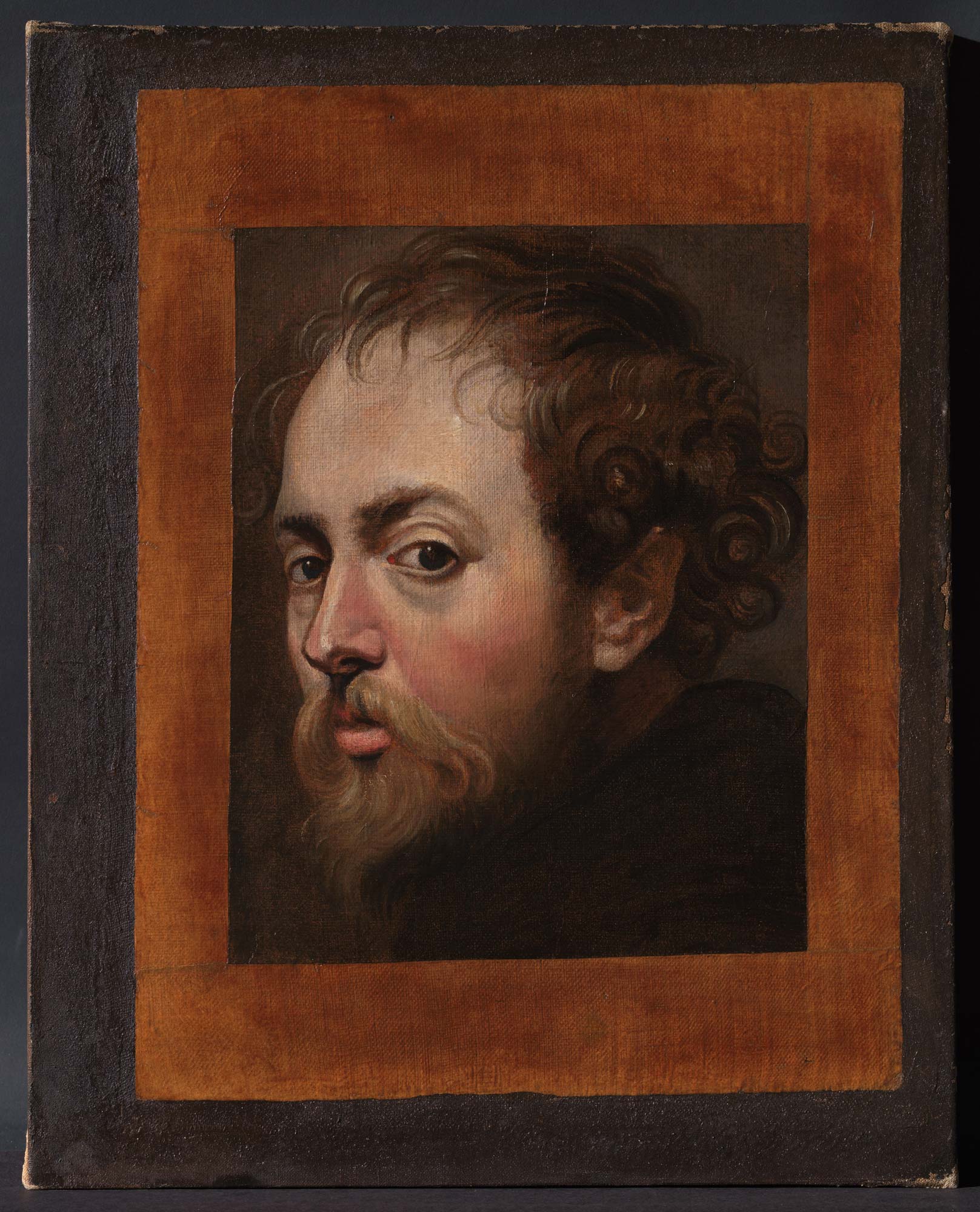

Rubens in Genoa neither has the pioneering character of Rubens and Genoa, nor is it configured as an organic exhibition like The Age of Rubens (which, moreover, extended to the other “Rubensian” venues in Genoa: even then, the Jesus works were listed as parts of the exhibition, though they had not left their locations, and there were sections in Palazzo Rosso and Palazzo Spinola), however much the stated intent is to reconstruct “what the artist saw, who he met, who he knew” during his time in Genoa: it can be considered, if anything, an exhibition of addenda, not necessarily related to Genoese events, which is why the visiting itinerary may be tortuous and uneven. The introduction is entrusted to the study that Rubens made for the lost figure of the halberdier of the Trinity of Mantua, in which the artist portrayed himself: the work, an oil on paper, was published by Michael Jaffé in 1977, and traced back to the Mantuan altarpiece by Elizabeth McGrath in 1981, a hypothesis on which Ugo Bazzotti’s 2016 concurring opinion is also recorded on the occasion of the study day on the very Trinity held that year at the Ducal Palace in Mantua. The recent purchase by a private collector and the loan to the Rubenshuis in 2020 have drawn attention to the work (presented as “a new Rubens self-portrait” when it was exhibited in Belgium in 2020, but in fact already known, as we seen, since the 1970s), which was thus also able to arrive in Genoa to sanction the start of the exhibition, which continues with the display of theeditio princeps of the Palazzi di Genova, and is followed by a section on “Marvelous Genoa” divided into four parts: one with the funny title “Rubens in Love,” one on the gardens of the noble palaces, one on Rubens’ “friends,” and one on the model of the Miracles of St. Ignatius of Jesus. In recording an interesting novelty in this section, namely the discovery in a French private collection of an unpublished sketch of the Miracles of St. Ignatius, of uncertain attribution, placed in direct comparison with its counterpart study preserved at the Dulwich Picture Gallery (it is however, even with the uncertainty, a work of undoubted quality representing, in all likelihood, a more advanced stage of work than the English sketch), it is worth dwelling on the motivations that led Rubens to “fall in love” with Genoa, if one is to follow the title of the first subsection: they are deeper reasons than the painter’s sudden infatuation with the city’s vocation for trade and finance, its wealth, culture and sophistication, and the resourcefulness of its ruling class.

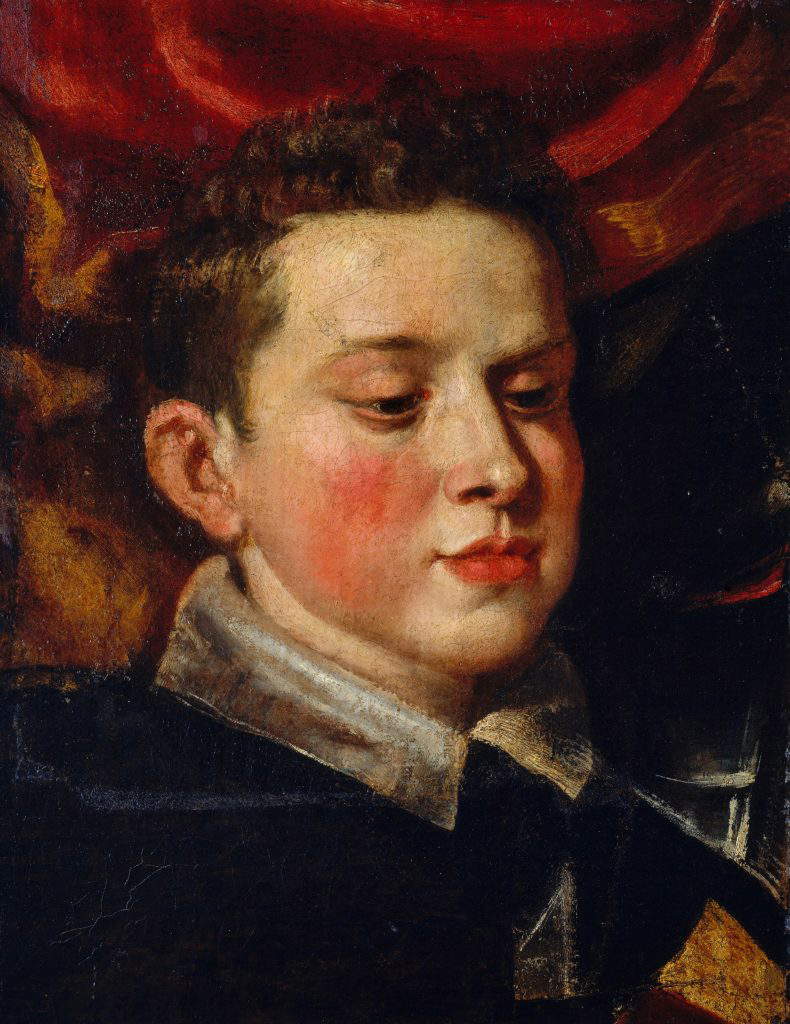

The component of “wonder,” in the exhibition evoked especially by the pair of paintings by Jan Wildens and Gerolamo Bordoni’s View of Genoa, was certainly common to many who came from afar to a splendid city that did not fail to subdue with its charm even the young Rubens. But there was much more. Reasons of a social nature, meanwhile: Rubens came from a bourgeois family, and as one born and raised in an environment that identified prestige (and success) with the results of the product of one’s own ingenuity and hands, the young artist could not fail to be captivated by a wealth that was the fruit of work, trade, and finance. And, as Giorgio Doria reconstructed, Rubens saw in Genoa the tangible image of opulence (and money, of course) produced by the very social class from which he came (his own family, despite the fact that his father was a lawyer, had mercantile traditions): an image reinforced by the “ubiquitous presence of Genoese capital,” in Flanders as in Germany as well as in Mantua, all places to which the young Rubens traveled during his career and which likely led him to get a feel for the city even before he arrived there, especially when placed in comparison with his own Antwerp, which in the early seventeenth century was beginning to recover from an economic crisis that had hit it in the latter part of the previous century. The Genoa Palaces, incidentally, could also be interpreted as Rubens’s desire to offer a stimulus to the Antwerp merchant bourgeoisie, a spur to emulate what the Genoese oligarchy was doing. And probably a far from secondary role must be assigned to Rubens’s first master, Otto van Veen, a Flemish painter who had worked for a long time for Cardinal Alessandro Farnese, an educated artist, a lover of classical literature and a connoisseur of Italy, whose frequentation could not fail to leave its mark on the young Rubens then in training. In addition, as Anne T. Woollett has recently written, perhaps it cannot be ruled out that Rubens left Antwerp for Mantua in the fall of 1600, armed with a letter of recommendation penned by Van Veen. The next section of the exhibition focuses precisely on Rubens’s arrival in Mantua, which was crucial to his subsequent stay in Genoa, given the relations that the city of the Gonzagas had had with the Republic since ancient times, and which had intensified precisely at the turn of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries (moreover, some of the bankers of Duke Vincenzo I Gonzaga were to be Rubens’s commissioners), but it remains on the surface, although there is an interesting moment of comparison between an important work such as the fragment of the Trinity with the portrait of Ferdinando Gonzaga infante, kept at the Magnani-Rocca Foundation in Traversetolo, and the aforementioned portrait of Vincenzo I di Pourbus from the Rizzi Gallery in Sestri Levante, which was once given to Rubens.

Then come two more sections evoking the Genoese milieu: one on the city’s literary milieu, another reason for Genoa’s fascination with Rubens (there is a portrait of Gabriello Chiabrera executed by Bernardo Castello, some of the most read of the time, above all Torquato Tasso’s Gerusalemme liberata, and a workshop painting, Hero and Leander, believed to be a replica of a lost work but also known through another replica, albeit of higher quality than the one on display in the exhibition, and exhibited at the Gemäldegalerie in Dresden), and one on Genoese families. Presented here is a St. Sebastian from a private German collection that is not only attributed without doubt to Rubens, but is also traced back to the commission of Ambrogio Spinola on the basis of the will of his son Filippo, found during the studies conducted for the exhibition in the State Archives of Alexandria, and which testifies to the presence of an “imago S.ti Sebastiani de manu Rubens” in his collection in 1655. Prior to this finding, the last record of the painting was in 1722 (a date when the “Saint Sebastian Medicated by Angels” appears in the palace of Carlo Filippo Antonio Spinola Colonna, formerly the home of Ambrogio), after which there is no further record of it. It is hard to understand why in the exhibition the painting, of which another version is known, the one in Palazzo Corsini in Rome, slightly different in composition but appearing decidedly more powerful as well as more studied in the rendering of the flesh tones and light effects, is unhesitatingly given to the hand of the master alone. Indeed, it should be specified that in the recent guidebook of the Rubenshuis in Antwerp (2020), where the work is on long-term loan, the painting is assigned to “Rubens and workshop” and it is explained that even on the dating there is still uncertainty, while in the catalog of the exhibition Becoming famous. Peter Paul Rubens, held in Stuttgart in late 2021 and early 2022, Büttner himself, while considering the identification of this dipito with that of the 1722 inventory as likely, recorded it with a question mark beside Rubens’ name: since the only significant change is the discovery of the 1655 document, which at most provides evidence for tracing a Saint Sebastian back to the commission of Ambrogio Spinola, but as is also written in the catalog there is an information gap between 1722 and the date of the recent appearance of the painting in question on the market, it is unclear why the question mark that accompanied the painting in Stuttgart disappeared. On the other hand, we know much better the story of theHercules and Deianira displayed nearby and regular presences in all Genoese exhibitions on Rubens: they are not only works that attest to the relations between Ligurian collectors and the Flemish painter, but they are also remarkable summaries of the sources that inspired him, between classical antiquity and Michelangelo, between Carracci’s lesson and that, even more evident, of Titian. Unfortunately, no works appear in the exhibition to better contextualize Rubens’s figurative culture: instead, one will find, just after the Turin works, an interlocutory section devoted to genre painting and still lifes to give a glimpse of the tastes of the Genoese patrons.

The section on portraiture, about which, moreover, there is an appendix at the end of the exhibition, seems inconsistent, since the curators preferred to display Buscot Park’s portrait in a separate chapter on Genoese ladies with the emphatic title “Genoa paradise of women,” a reprise of a comment by Enea Silvio Piccolomini who, two centuries before Rubens, referred not only to the luxuries that Genoese women surrounded themselves with, but also (and especially) to the freedoms they enjoyed: despite the fact that the room apparatuses imply that the section intends to address the “revolution” in portraiture brought about by Rubens, despite the fact that the name of Titian is evoked (of whom not a single work is included in the exhibition, just as there are no works by Venetian painters), despite the fact that the artists appreciated by the Flemish painter are listed, the section resolves itself into a comparison between, on the one hand, the Portrait of a Lady in a private collection in Heidelberg, for which a hypothetical Mantuan provenance is proposed for the first time, and that of Giovanna Spinola Pavese kept in the National Museum in Bucharest (and dependent on a similar painting in a private collection, in whose effigy Orlando proposes to identify her sister-in-law Maria Doria Pavese: the work is not on display), and on the other a selection of works by Bernardo Castello, Luca Cambiaso, Guillem van Deynen. In short, if the intent of the room seems almost to be to address Rubensian portraiture as a whole, the selection, on the contrary, does not extend beyond the Genoese borders. As for the portrait of Buscot Park, on the other hand, which the audience, as anticipated, will find a few rooms later, again it is accompanied by a new hypothesis: in particular, an identification is proposed with Violante Spinola Serra, sister of the Veronica effigyed in an almost identical portrait preserved at the Kunsthalle in Karlsruhe (Anna Orlando’s idea is that Rubens painted, with few differences, portraits of two very similar sisters, albeit separated by six years of age).

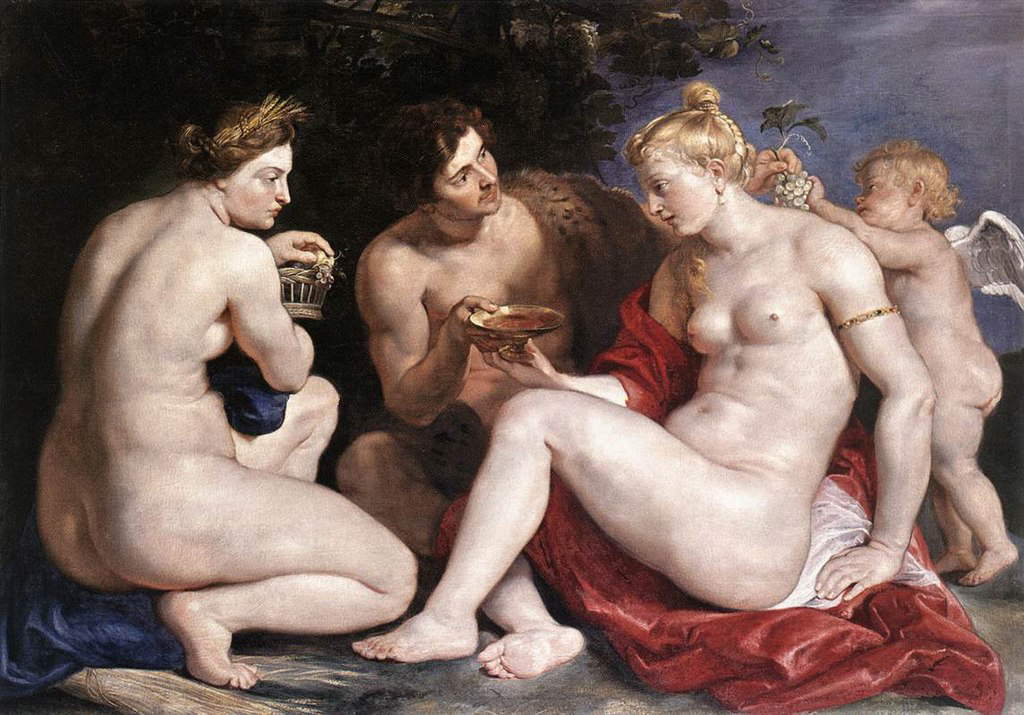

In the four rooms between the one in which the portraits were placed and the one in which the Buscot Park painting was placed, the motif of the “four elements” was found to justify a sort of potpourri in which everything meets, with the idea of taking the visitor into the “fantastic universe that Rubens reproduces with his immersive, 360-degree art,” as the room panel reads. The “earth” element is associated with a variant, preserved in a private collection, of the Pieta of Rudolf of Habsburg kept in Madrid, executed by Rubens in competition with Jan Wildens and recently the protagonist of a tasty provincial affair (after it resurfaced it was exhibited for the first time in 2015 in Matelica, and a controversy ensued between the majority and the opposition regarding the authenticity of the painting, about which no doubt hangs, although the Madrid version is of higher quality), and a replica of the Hermitage’sHomage to Ceres. The section on air is opened by theTree with Peacock hitherto believed to be the work of Sinibaldo Scorza (and so it also appears in the Rubens catalog in Genoa), but the panels in the room inform that, shortly before the departure of the exhibition, the attribution was changed in favor of Jan Roos (it will be necessary therefore, understand separately the reasons for this change of attribution), while the room on the water contains Susanna and the Old Men from the Borghese Gallery, and a sketch, from a private Swiss collection, of the Discovery of Erythonius kept in the collection of the Princes of Liechtenstein. Finally, we move on to fire, here understood as a symbol of passion, whose protagonist is one of the best Rubensian works in the exhibition, Venus, Cupid, Bacchus and Ceres from the Gemäldegalerie in Kassel, set against some paintings of mythological subjects by Luca Cambiaso and Giovanni Battista Paggi, on the grounds that Cambiaso’s nudes inspired Rubens despite the strong generational gap (exactly fifty years of age: the Genoese died when Rubens was eight years old), and that Paggi is “considered a leader when Rubens is in Genoa.” The comparison between Cambiaso and Rubens constitutes perhaps the most successful moment of the exhibition and evokes an essay exactly seventy years ago by Bertina Suida Manning, who compared the two artists in the Gazette des Beaux-Arts in 1952. In this case, the most pregnant comparison was between the Rape of the Sabine Women frescoed by Luca Cambiaso in the Villa Imperiale in Terralba, and Rubens’s Rape of the Leucippides (now at the Alte Pinakothek in Munich), in order to recognize that the Flemish artist’s painting recalls quite clearly the central group of Cambiaso’s fresco (the abducted woman and the abductor appear in an almost identical) and thus highlight the debts that Rubens owed to Cambiaso, another artist whom it is possible to include among those who offered cues to the great Flemish (“in several compositions of Madonnas,” Suida Manning would later write, returning to the subject in her monograph on Cambiaso, “he recalled the religious idyll” expressed by the Genoese artist in the Madonna and Child with St. John in the church of Santa Maria della Cella in Sampierdarena).

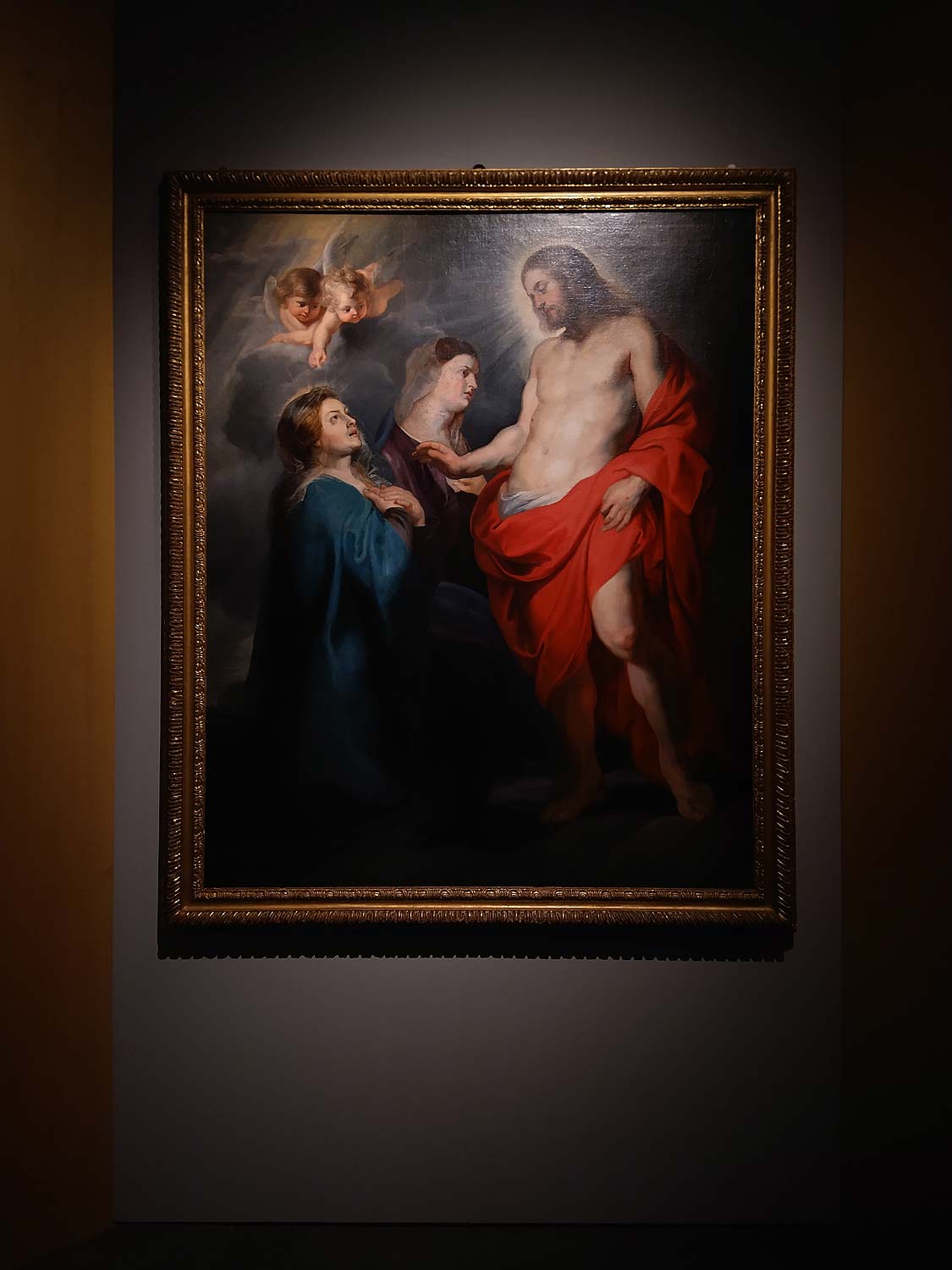

After the room on women, which comes at this point in the exhibition, one enters the Doge’s Chapel (which one would always like to be free of arrangements, as we reiterate on every occasion here, but evidently it seems to be impossible to avoid touching this very important room) where a small focus on the sacred Rubens it includes a small canvas preserved at the Salzburg Museum in Salzburg, depicting St. Gregory between Saints Maurus and Papias, and St. Domitilla between Saints Nereus and Achilleus, an early version of the altarpiece at Santa Maria in Vallicella in Rome, and a sketch for the Circumcision at the Gesù Church (which, on a hunch, should constitute the fifteenth section of the exhibition, since the numbering goes from 14 in the section in the Doge’s Chapel to 16 in the last room, skipping a number at the teletta). The last room presents what is perhaps the main novelty of the exhibition, the discovery of a resurrected Christ that is thought to be the one mentioned as a work by Rubens in a nineteenth-century Genoese inventory, and thought to be lost, but hitherto known anyway through seventeenth-century engravings. The Christ on display was painted on a canvas that had already been used, as could be discovered through x-rays (the artist repainted the figure of the Madonna): the painting was displayed, at the curators’ behest, while restoration was in progress, so that it is possible to see two women facing Christ. It is, in fact, the same figure (the Virgin), depicted in two different poses: the more recent one is the Madonna in blue, further away, while the other dates from a “first state” of the painting, the one reproduced in Egbert van Panderen’s seventeenth-century engraving. This “first state,” writes Fiona Healy, who was responsible for compiling the record, "stylistically [...] falls perfectly within Rubens’s production of the years 1612-1616, as is particularly revealed by the modeling of Christ’s muscular body, which in pose and appearance is reminiscent of Michelangelo’s Christ of Minerva in Rome. Moreover, the subject of the Virgin interceding before Christ is also typical of Rubens’ production in the 1610s.“ We do not know why Rubens then decided to modify the composition, nor do we know to what extent the interventions on the work can be attributed to his hand. ”The conservative condition of the visible part of the first state sno compromised and makes attribution difficult,“ Healy explains, ”although the apparently mechanical execution of the Madonna suggests the hand of an assistant.“ As for the ”second state,“ the scholar associates only the Virgin’s head and the rightmost angel with Rubens’ brush. And it therefore appears in the exhibition as the work of Rubens and workshop, although it is a painting that will need further study: not to be ruled out is the idea that the first state is a workshop replica of a lost original on which the master may have later intervened (as a result, the face of the Virgin in the ”first state" will most likely be covered again).

It is a pity that such an interesting painting, and one linked to Genoese events, reaches only the last stage of a journey that is not lacking in new ideas (it is worth mentioning a second unpublished work in addition to the hitherto unknown sketch for the Miracles of St. Ignatius: it is a tapestry that is part of the continuation of the stories of Decius Mure, executed on a cartoon perhaps from Rubens’ workshop, while the discovery of the Risen Christ was made known in 2020), but which appears too diluted and unbalanced: Understandable is the desire to present an exhibition with new proposals, even where they appear unclear, and with works that have never been exhibited before, but the propensity for the unseen and the possibility of seeing works never seen or never shown in Italy should not be separated from the setting up of a complete and defined itinerary. In spite of some sharp points (the comparison between Rubens and Cambiaso, the last room with the Resurrected Christ that condenses the beginning of a scientific investigation in a section that is decidedly interesting even for the uninitiated), there are in fact many tiring passages: the little space given to the Palazzi of Genoa, which also provided the pretext for the exhibition (it is true that this can be remedied with Sara Rulli’s essay in the catalog, but in the itinerary the presence is hardly noticeable), a section on Genoese families that is meager, as as the section on portraiture, the lack of a dense focus on Rubens’ figurative culture and, conversely, the presence of some not so fundamental passages (the one on animals, for example, or the one on genre scenes). Add to this a major shortcoming in regard to the visitor who is not necessarily familiar with Rubens’ Genoese background: the absence of any clear invitation to go and see Rubens’s works scattered around the city, two of them just beyond the piazza, and if it is true that an exhibition should lead to a greater awareness of the territory to which it refers, perhaps this element should have been better handled, as was done for example for the excellent exhibition The Form of Wonder that preceded the one on Rubens and which, on leaving the Ducal Palace, projected the public toward the city. The exit from Rubens to Genoa, on the other hand, is not as clear and, above all, leaves the feeling of having visited an exhibition that is not fully resolved.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.