It was 1986 and Fabrizio Plessi brought to the Venice Biennale that year one of his most famous installations, Bronx, indebted to a certain extent to the art of Nam June Paik: twenty-six televisions arranged inside an iron structure, with the monitor facing the ceiling of a narrow, dark room, twenty-six shovels stuck in the middle, and their reflections creating the effect of water on the screens. In the pages of the New York Times, Michael Brenson, art critic of the American newspaper, wrote that Bronx was the most dramatic installation in the entire Biennale. Then, twelve years later, Plessi arrived for the first time with a solo exhibition of his work in America, at the Guggenheim Museum’s SoHo location, which opened in 1992 and closed ten years later. The task of reviewing then fell to Grace Glueck, who was able to capture in two lines the meaning of Plessi’s art: “to use technology to empower and interpret the mysterious realms of nature and history, mixing the virtual with the real, so to speak.” Then as now, Plessi was interested in capturing the movement of water and fire, as well as the passage of time.

Today’s Plessi is perhaps no longer the experimental artist of the 1980s and 1990s: one of Italy’s best-known artists, appreciated probably more abroad than at home, he has exhibited everywhere, often with projects that are anything but successful, constrained within dimensions that are little more than decorative (one above all: the 2020 Christmas tree in Venice), or simply cadenced, revisitations of previously proposed works that do not escape the déjà-vu effect. An artist who, from the early 2000s to the present, has always been true to himself: when, however, he is not obliged to force himself, Fabrizio Plessi’s art is able to release all the tension that sustains his works. Plessi’s most recent project is entitled Plessi marries Brixia, and it is a series of five interventions that the Emilia-Venetian artist is bringing to Brescia, to the spaces of the Santa Giulia and Capitolium, in the year that the Lombard city is the Italian capital of culture. They are partly works that have already been seen, and the unseen ones are not even among the most interesting of the group. And yet they are also interventions that draw strength from the context that hosts them, which is particularly congenial, in the case of the project curated by Ilaria Bignotti, to exalt the electronic neo-Baroque of this artist who has been working with video for more than forty years, although he tends to reject, rightly, the definition of “video artist.” Plessi, rather than the younger “video artists” who now increasingly come forward with exhausting films or documentaries with a cinematic slant, resembles, we might say, a sculptor. Plessi sees video in the same way a sculptor sees marble: his works have to do with forms, with light, with movement, rather than with narrative content (indeed, there is no narrative in Plessi’s works). Video allows him to operate in the same way a sculptor works with a chisel, adding in addition the temporal dimension: “A manipulated, compressed, heterogeneous, synchronic time that the artist uses at will without respecting chronologies,” wrote Alberto Fiz. “His goal is to create a total, Wagnerian work of art in which sound, architecture, sculpture and technology coexist, broadening the spectrum of vision.”

Plessi is an artist who makes the natural coexist with the artificial, the ephemeral with the eternal by using video not as a grammatical structure, but as a poetic medium that enhances the baroque opulence of his visual imagery. Video, in Plessi’s work, “is encompassed,” Achille Bonito Oliva has written, “in its values as a container, as a transmitter of images and sounds, as a box that punctuates space, as a simulacrum and as a temporal stabilizer. The occupied space is invested, and therefore altered, by projects linked to an imaginary capable of measuring itself with technological complexity and with the deep structures of the psychic universe that are activated by reference to primary and elementary materials such as water, fire, air and earth.” The “evocative power to refer back to nature and its movements,” as Bonito Oliva called it, in Plessi’s work is strong even when his works do not have nature as their subject matter, but stand in relation to antiquity, as in the case of the works that punctuate Plessi’s Brixia bridal path.

Plessi’s idea is to celebrate a kind of marriage between himself and the city and its inhabitants in order to deliver, the introductions state, “a message of responsibility and awareness of Brescia’s historical, archaeological and iconographic heritage”, through a “journey that highlights the vestiges and heritage of the city, reinterpreting them through Plessi’s characteristic technological and multimedia alphabet, that is, with light, sound and moving images.” Beyond the perhaps somewhat naïve (and even a little immodest, one might say) nature of the project and the intentions behind it (we have never heard of an artist cultivating the intention of marrying an entire city, although beyond the gimmicks the metaphor could be read in a more profound way, meaning the artist’s act of fidelity to the city’s heritage.act of fidelity of the artist towards those who preceded him, as if to say that even the most radical and subversive artists cannot help but forget the past), it is undeniable that the wonder aroused by Plessi’s electronic sculptures results as if amplified by the traces of Brescia’s ancient past, although the artist’s procedure is not new: working on the collective memory of a place to transcend the particular and touch the universal. When Plessi’s works measure themselves against ruins, his attitude does not deviate too much from the sentiment of the artists who have preceded him in the last two hundred and fifty years, at least from Füssli onward: they express the restlessness of the human being before his fate. In his case with a sense of electronic sublime, we could call it, which translates into the forms of archetypes in motion what can be observed, in Brescia, among the rooms of the Santa Giulia, and which adds the dimension of time by transporting the relative on a temporal vector that is both linear (past, present and future) and cyclical. Plessi began to confront the past in this vein at least from the 1987 edition of Documenta in Kassel, where he presented Rome, a scenographic installation in which the artist imagined a kind of ruined triumphal arch, made up of stones and videos with images of flowing water: thus, with this theatrical, high-impact installation, Plessi entrusted his restlessness, his wonder, to the images. Then, in the following thirty years, his feeling was expressed in works characterized by a greater immediacy, and also by a more obvious ease, we might say, but his works have not lost their charm, nor has their evocative power diminished.

There is no set path to immerse oneself in Plessi marries Brixia. Usually visiting Santa Giulia from the section dedicated to early medieval art, consequently the first work one encounters along the visitor’s itinerary is one of two unseen works, Floating santa Giulia: here, the artist has translated one of the museum’s best-known works, the 17th-century crucified Santa Giulia attributed to Giovanni Carra, into video, giving it movement and a golden facies . The draperies of the sculpture, in Plessi’s video, are stirred by a light breeze intended to take on the meaning of the flow of time and history: the contemporary visitor becomes a witness to the sacrifice of the martyred saint on the cross. On the other hand, the strength of his faith alludes to the gilding, a typical element of Fabrizio Plessi’s recent works: gold, for him, refers to light, to incorruptibility, it is the “dream of a better world,” as he himself said in an interview. However, gold also recalls vanity, the ephemeral nature of existence: this is emphasized by Plessi himself in some of the drawings that make up the second section of the exhibition, La mia testa è un foglio A3, set up in the Sala dell’Affresco. Here, the public gets to see some 80 drawings for projects related to the exhibition, which began taking shape in 2020. An opportunity, then, to learn about the artist’s creative process (Plessi himself said that drawing is a kind of biological necessity for him), to see up close how his imagination works before his works take shape, to also read some of the artist’s comments on his works. For example, a slightly revised Shakespearean quote (fromHenry VI) recurs on some of the sheets: “Glory is like a golden circle of water that never ceases to widen until it dissipates into nothingness.” This is the sentiment that animates, for example, the Colonne colanti, a work in the Roman section of the Santa Giulia: three screens with as many images of Corinthian columns, at first stable, sumptuous, magnificent, and then set off toward a process of disintegration during which we see them melting and dripping to the ground until they disappear. The idea of the dripping column is not new: back in 2019 Plessi presented a similar work at the Baths of Caracalla in Rome. In his imagery, the column represents the attempt of elevation towards eternity, frustrated by the finiteness of our existence: to a “pessimistic” connotation, so to speak, Plessi adds, however, also a more propositional one, as if to say that the ruins of the past are the legacy of history and, as such, they guard values, reason why it is necessary to take care of them.

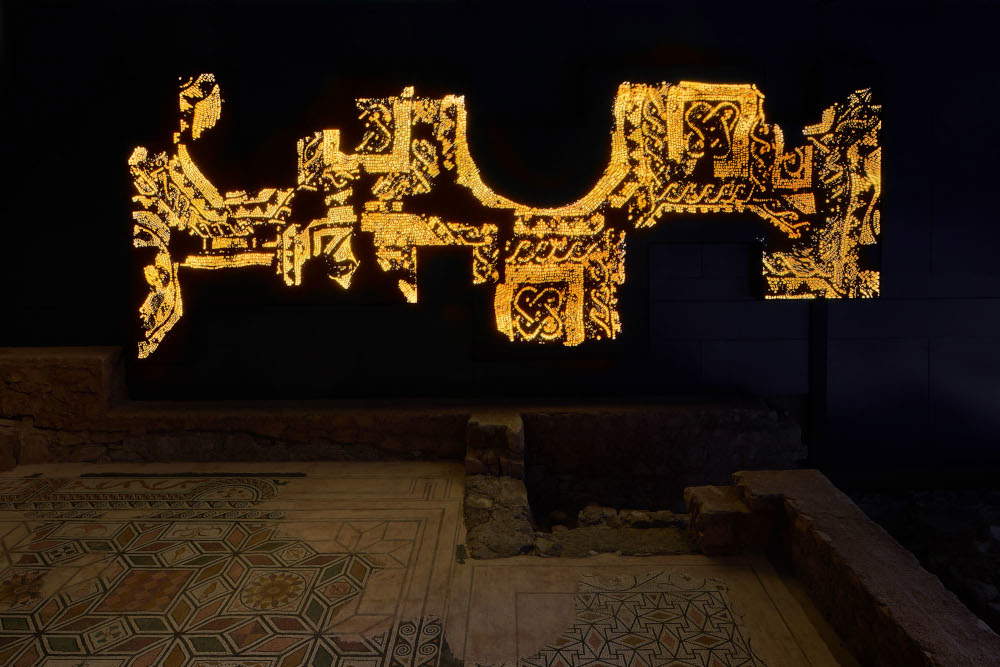

Also in the Roman section is Underwater Treasure, another revisitation of previous works: here, the mosaics of Roman Brescia are submerged by water, another element present since the beginning of Plessi’s research. The flow of water continually conceals and reveals the forms of the mosaic floors of ancient Brixia, alluding to the action of the merciless passage of time on the works of human beings and to our memory, floating among the waves of history. We then move on to the basilica of San Salvatore, where we admire another completely new intervention, created specifically for this place: Plessi marries Brixia, the work that gives the exhibition its title, is a monumental ring of gilded metal that alludes to the artist’s union with the city, and within which a golden fluid flows, as a symbol of rebirth, transformation, palingenesis. A work with positive overtones, “the ring,” the guidebook reads, “becomes a powerful icon and an incitement to education, love and respect for history,” being “the symbol of the trust and loyalty of art to the public, and of the public to art: the viewer in fact establishes with the work a dialogue and exchange based on reciprocity and recognition of common values.” The ring is certainly the most scenic intervention in the exhibition: it occupies in height almost the entire nave of the basilica of St. Savior, although, as with all the other interventions in the exhibition, its juxtaposition to historical spaces is respectful, also taking into account the fact that the basilica is a musealized space and has hosted in the past other perhaps even more impactful interventions, such as Navarro Baldeweg’s in 2020. However, it is also the most didactic and easy work of the five that Plessi has brought to Brescia. Finally, the tour ends in the Capitolium, where the public admires Capita aurea: three large black screens with as many bronze sculptural heads that gradually melt until they drip and disappear in a pool of liquid metal, which then, in turn, will eventually disappear in the eyes of the relative, leaving the screen black: after which, the cycle begins again. Again, another vanitas: time flows and dissolves earthly glories, and then is reborn from its own ashes.

Plessi marries Brixia continues the trend of exhibitions in which the artist is confronted with the heritage that comes to us from the past: he had already tried his hand at similar operations, just to cite the two most recent examples, in Venice(The Golden Age) and Rome(The Secret of Time), and then back to exhibitions in the Valley of the Temples in Agrigento or in the Camera dei Giganti at Palazzo Te in Mantua. Not as of today does Plessi suffer the fascination of ruins, not as of today does he feel the call of antiquity provoking his imagination, and above all the intent to restore the work of art to the passage of time animates thePlessi’s art from the very beginnings of his career, as does his desire to liberate warmth and humanity from a medium usually considered cold, distant, algebraic such as video. “To the society of spectacle and television spectres, languages in which the digital has delegitimized the symbolic,” wrote Marco Tonelli, “Plessi opposes the spectacle of the work of art as a return into the symbolic or rather into the flow of history.” A fluid medium such as video will therefore be particularly conducive to the artist’s poetics, especially if the idea is to measure itself against history.

Plessi’s work itself, in a manner entirely consistent with his intentions, is ephemeral, and when the exhibition is closed will most likely survive only in the memories of those who have seen it, or at most in drawings. The poetry of Plessi’s works, at once technological and primordial, lies in their ability to bring the relative closer to an impalpable matter, be it water or flowing time, in the momentary, fleeting and unrepeatable encounter with a projection in motion that renders to the viewer the essence of what he sees. And it is also for this reason that his works, his sculptures made of video, have much more to do with the real than with the virtual.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.