by Federico Giannini (Instagram: @federicogiannini1), published on 01/06/2018

Categories:

Exhibition reviews

/ Disclaimer

Review of the exhibition 'De Prospectiva Pingendi. New Scenarios of Italian Painting' in Todi, Palazzo del Vignola and Palazzo del Popolo, April 22 to July 1, 2018

Next year will mark the 50th anniversary of Autoritratto, the seminal essay with which Carla Lonzi redefined the boundaries of the art critic’s profession, which she herself, after the publication of that writing, decided to abandon. The meaning of the conversations with artists(Lucio Fontana, Enrico Castellani, Pino Pascali, Carla Accardi and others) that Carla Lonzi had collected in her volume lay in the need to make the work of art perceived “as a possibility of encounter, as an invitation to participate addressed by the artists to each of us: a possibility that leads the artist to be ”recalled into another relationship with society, denying the role, and therefore the power, of the critic as a repressive control over art and artists, and especially as an ideology of art and artists ongoing in our society." It is from Carla Lonzi that one can begin to read the exhibition De Prospectiva Pingendi. New Scenarios in Italian Painting, underway in Todi, in the dual venue of Palazzo del Vignola and Palazzo del Popolo, until July 1. Even the curator of the Umbrian review, Massimo Mattioli, prefers to step aside and leave it to the artists (or rather: the artworks) to speak for themselves. “The best curator is the one who is most able to stand aside, letting art present itself,” Mattioli sentences in his highly enjoyable catalog essay, written in the form of a short story.

Letting art present itself: but what does art and, specifically, Italian painting of the 2000s have to say? It is necessary to start from a premise: if art is the manifestation of a feeling and a consequent action that are linked, in an almost symbiotic way, to the historical, social and cultural context in which art itself is produced (“between art and society,” wrote Franco Ferrarotti, “there runs a real, dialectical, living relationship,” a relationship that “does not allow itself to be expressed, much less imprisoned, in the schemes of aestheticising formalism and naive socialism,” with the consequence that art participates “in a concrete human experience , determined and meaningful”), then in a liquid society any centrality and any systematic vision of the artistic journey, Fabio De Chirico suggests in the catalog, is eroded by the sudden and continuous changes our society is undergoing, with the result that the actuality of art is marked by “dissemination, by the deflagrating multiplication of genres and languages, by the incessant fluid flow of technological experimentation.” Fragmentariness is the figure that most clearly and consistently marks the art of our times, especially in Italy where, since the early 1990s, there have been no groups capable of centralizing trends, modes and ideas (at least according to Mattioli’s vision, which identifies Transavanguardia, Anachronismo and the Scuola di San Lorenzo as the last choral experiences of Italian painting). A fragmentary nature that therefore prevents the provision of a secure and stable characterization of Italian art, as noted in the catalog by Daniele Capra, who aligns himself with the positions of many who, in recent times, have agreed that it is difficult, if not impossible, to identify founding elements (or identities, some would say).

A starting point, it would seem to be guessed from the title of the exhibition, which refers to Piero della Francesca’s famous treatise, could, however, be the recovery of tradition: already in unsuspected times, Giulio Paolini asserted that the prevailing trait of Italian artistic identity is precisely its reference to tradition. And these references can only find their most natural field of action in painting, also by virtue of the fact that, Fabio De Chirico again points out, “painting today appears as a possibility of revenge against forms of experimentation that are an end in themselves and are now hysterified by a system of exasperated commodification.” In other words, it seems to read between the lines that proposing a canon of contemporary Italian art is a very arduous undertaking (and Mattioli, in tackling it, has shown himself to be particularly courageous, for many reasons: because the Italian exhibition scene is full of tired and stale collectives, because every choice always entails exclusions, and in Todi there are some excellent ones, and because staging an exhibition of this kind is tantamount to taking a precise and clear stance). However, if it is up to us to try our hand at such a task, painting, comforted by its being a medium to which we in Italy are so strongly attached, by its constant tension between experimentalism and tradition, as well as by its undoubted commercial appeal, cannot but constitute the privileged terrain.

|

| Hall of the exhibition De Prospectiva Pingendi. New scenarios of Italian painting |

|

| Hall of the exhibition De Prospectiva Pingendi. New scenarios of Italian painting |

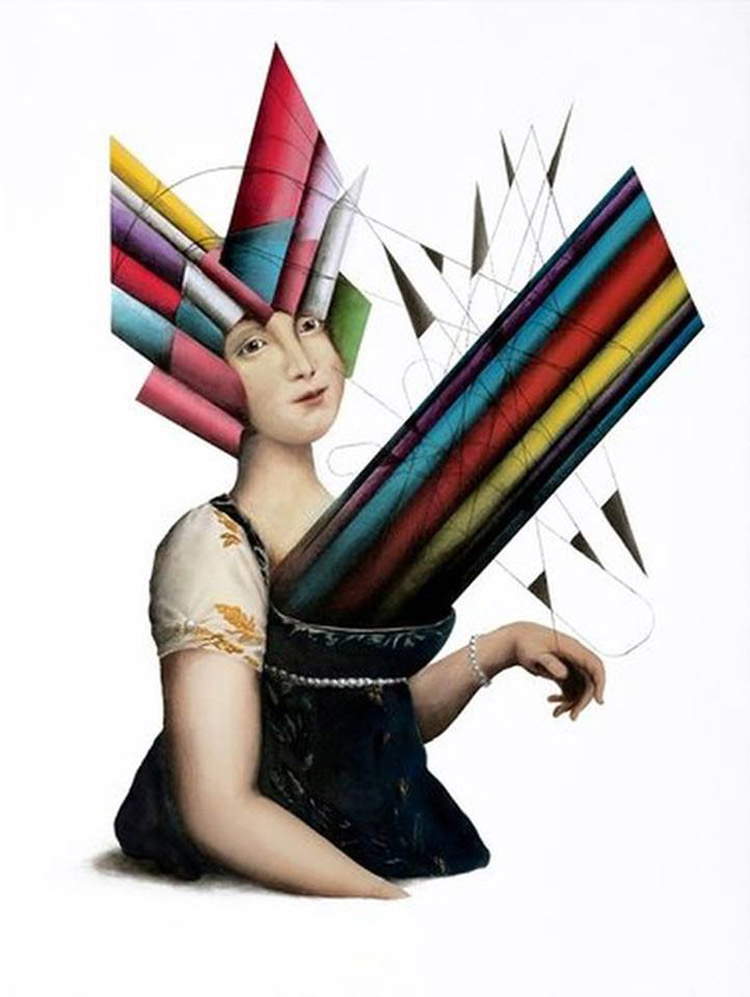

The reference to tradition marks the start of the itinerary, which makes us enter the first of the three areas of painting according to Piero della Francesca: “la pictura contiene in itself three principal parts, which we say are disegno, commensuratio et colorare.” By “disegno,” the first of the three parts, “we mean to be profili et contorni che nella cosa se contene.” And so it is that in the opening of the itinerary at the Palazzo del Vignola, the spectacular Atrocities of Saint George and Companion, a large-format oil on canvas by Thomas Braida (Gorizia, 1982), materializes: his cruel St. George raging on a defenseless little dragon seems to have come out of a Moreau painting and grafted onto a Böcklin landscape illuminated by Redon’s atmospheres, and above all he offers the relative a tale that takes up the tradition on a formal level but overturns it, with fierce sarcasm, on the level of content. Braida’s saint dialogues with The Fasting by Nicola Samorì (Forlì, 1977), a fully Baroque artist who violently enters seventeenth-century art to draw figures from it(The Fasting brings to mind Ribera’s saints) to be fleshed out, rubbed out, tortured, burned, and destroyed: particular forms of contemporary vanitas, reflecting on the ultimate state of the work of art, as well as on the fate of our existence. Samorì is then the protagonist, in the next room, of a (heartbreaking) confrontation with the hyper-marine kitsch of Nicola Verlato (Verona, 1965): the same format, ancient, that of the ribbed altarpiece, to give substance to Samorì’s tormented existentialism(St. Peter in Hell) and to Verlato’s hyper-realistic Texas yokel, who is agitating on the back of a bull in front of the drilling tower of an oil well enveloped in flames. The only merit of Verlato’s painting lies in the fact that the tower recalls the one by Andrea Chiesi (Modena, 1966) displayed on the opposite wall: Chaos 2 recounts with grim detachment the post-industrial landscape of his Emilia region (a bit like CCCP did, with whom Chiesi also collaborated). Closing the circle are the (boring) little figures by Simone Berti (Adria, 1966) who amuses himself, it is not clear why, by sticking elements escaped from constructivist compositions on the skulls of accomplished Flemish gentlewomen or 18th-century ladies.

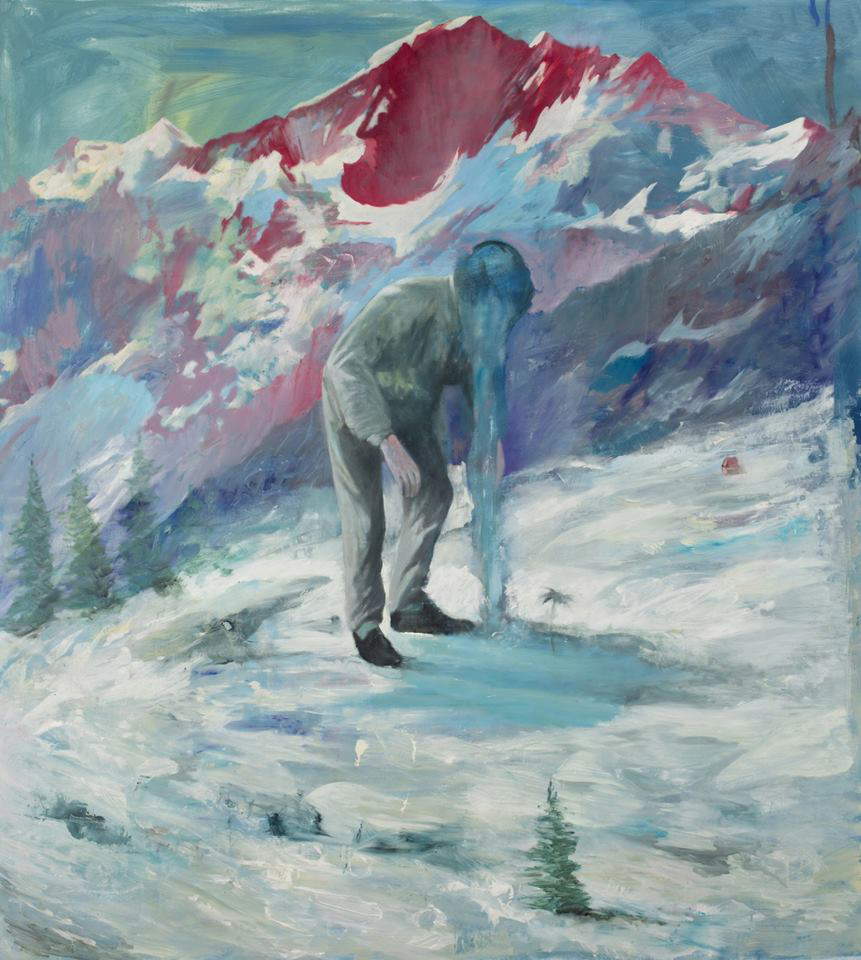

We continue in the rooms devoted to landscape painting, where the absolute protagonist is color, with which “we intend to give the colors commo nelle cose se dimostrano, chiari et uscuri secondo che i lumi li devariano.” Along come the evocative mountain paintings of Danilo Buccella (Liestel, Switzerland, 1974), a sort of Segantini in acid trapped within Nolde-like atmospheres, and who, in his triptych Shepherd, Rabdomancer and Narcissus, like Segantini yearns for an Alpine, almost pastoral serenity (although Buccella’s art is populated by visions far darker and more restless than those the public gets to appreciate in Todi). The uselessness of twentieth-century classifications of abstraction and figuration, “all the more so because they are understood by painters as stylistic options among possible grammars of expression” and no longer “categories that measure real adherence/adherence to/imposition on the world” (thus Daniele Capra) emerges when observing works such as those of Laura Lambroni (Olbia, 1981), who looks to science to create her refined compositions outlining electric fields and nebulae (“to investigate what we really are compared to electric fields or to the dense atmospheres where stars are born,” suggests the curator, merely paraphrasing, however, the artist’s thought).

|

| Thomas Braida, The Atrocities of St. George and Companion (2012; oil on canvas, 211 x 399 cm) |

|

| Thomas Braida, The Atrocities of Saint George and Companion, detail |

|

| Nicola Samorì, The Fasting (2014; oil on copper, 100 x 100 cm) |

|

| Left Nicola Samorì, Saint Peter in Hell (2016; oil on linen, 300 x 175 cm). Right Nicola Verlato, Beauty of failure (2009; oil on canvas, 312 x 152 cm) |

|

| Nicola Samorì, Saint Peter in Hell, detail |

|

| Andrea Chiesi, Chaos 2 (2010; oil on canvas, 140 x 200 cm) |

|

| Simone Berti, Carolina Murat (2017; mixed media on canvas, 80 x 60 cm) |

|

| Danilo Buccella’s triptych. On the left The Diviner, in the center The Shepherd, on the right The Narcissus (all 2017; oil on canvas, 190 x 160 cm) |

|

| Danilo Buccella, The N arcissus (2017; oil on canvas, 190 x 160 cm) |

|

| Laura Lambroni, Nebula rosetta (2016; mixed media on iron, 60 x 40 cm) |

One can thus pass without too much hesitation the other artists who base their expressive language on color. Angelo Bellobono (Nettuno, 1964) has produced far more interesting works than those that the public finds at the Umbrian exhibition, Antonio Bardino (Alghero, 1973), does not go beyond his misty, repetitive Romantic-Impressionist jungles, and Silvia Mei (Cagliari, 1985), proposes figurettes that some endowed with a strong sense of humor compare with unverifiable shamelessness to the works of the Co.Br.A. group, and certain others equipped with fervid imagination go so far as to call “neo-expressionist.” However, one can pause for a longer time in front of the works of Alessandro Cannistrà (Rome, 1975), who probes the extreme possibilities of color with compositions created by marking paper with smoke: the result is visions that aerial matter arranges in an almost random way, with procedures similar to those implemented a few decades ago by Burri, whose memory in Cannistrà’s art is impregnated with a romantic sensibility that identifies nature itself in the folds of the traces left by smoke.

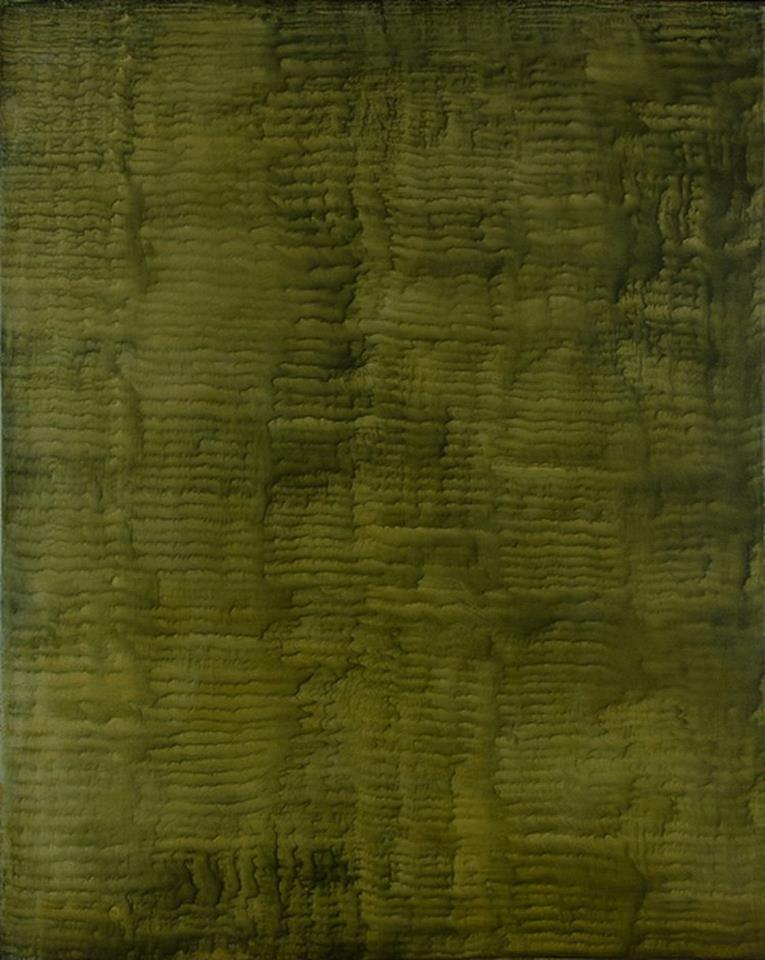

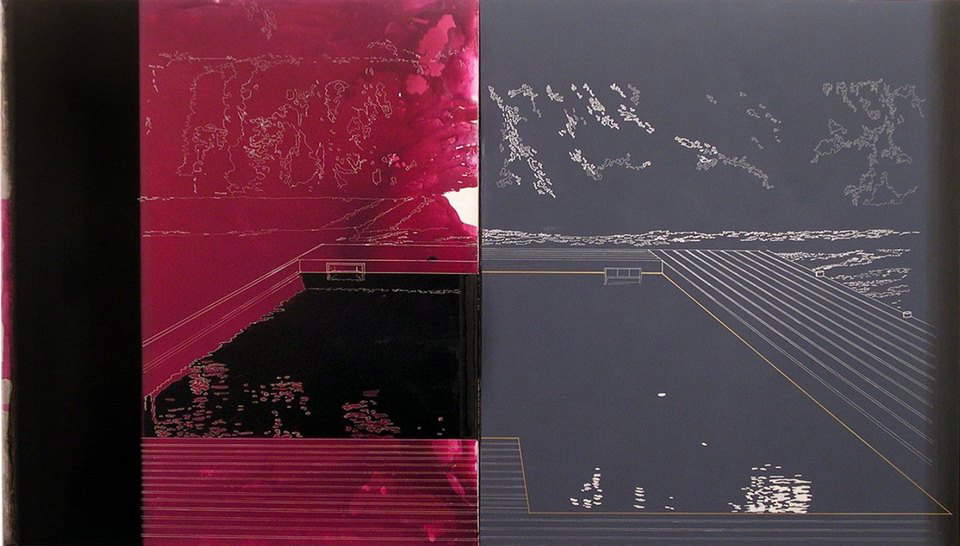

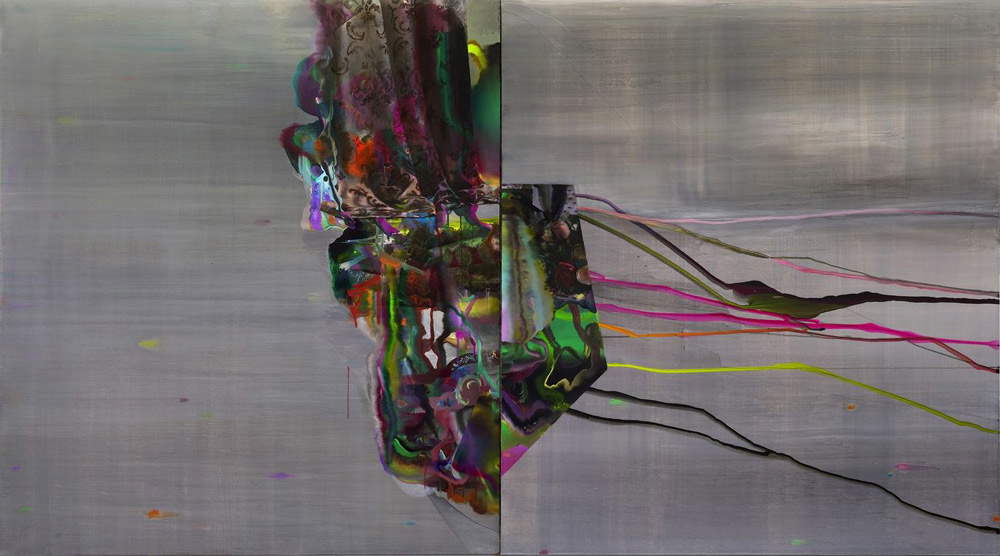

The last four of the fifteen artists Mattioli gathered in Todi, with their geometric research, give substance to the “commensuratio,” by which “we say they are profiles and contours proportionally placed in their places.” The first work one encounters is Gardens (Israel ) by Marco Neri (Forlì, 1968), a painting that offers the viewer the Romagna artist’s most typical stylistic signature: uniform backgrounds on which are grafted simple geometric elements that go on to compose recurring motifs on two-dimensional spaces and organize landscapes and architecture that respond more to a memory or a vision than to a view (“Israel” refers to the national pavilion of the 2001 Venice Biennial: the work is part of a cycle that recalls that edition of the Biennial, in which Neri played a leading role). Poets by Mario Consiglio (Maglie, 1968), with its ironic and minimal language, opens the last room where, in addition to the achievements of some of the above-mentioned painters “of color,” the visitor first encounters the surprising landscapes of Giuseppe Adamo (Alcamo, 1982), who with his acrylic colors manages to create incredibly illusory surfaces, which seem to escape from the physical limits of the support (and more than one visitor wondered if that surface was really smooth: it is), and finally the constructions of Gioacchino Pontrelli (Salerno, 1966), a painter whose purity is all reflected in his canvases: Untitled, for example, is a surreal perspective where dreamlike and rational meet.

One can then leave the Palazzo del Vignola to go to the Palazzo del Popolo where, in the monumental Sala delle Pietre, the large-format works of some of the fifteen artists in the exhibition unfold, again weaving the thread traced (admittedly a little more convincingly and with more timely comparisons) in the first venue. Among the most interesting works are Braida’s Clangori, which greet us immediately upon entering with their thunderous battle fought, however, by empty armor, or Pontrelli’s Mamma with its garish fabrics framed within geometric forms that melt into rivulets of color, or Neri’s very orderly analysis of the Town Center, a large installation of thirty-five acrylics on paper: thirty-five large windows that make up a fragment of an urban context marked by great geometric rigor, but also by life (because the shutters are raised or lowered at different heights, a sign that there is a story behind each of those windows).

|

| Angelo Bellobono, Scattered Lands (2017; acrylic, soil and oil on canvas, 200 x 200 cm) |

|

| Antonio Bardino, Untitled (2013; oil on canvas, 30 x 30 cm) |

|

| Silvia Mei, Bracciateste and red robe (2014; acrylic and mixed media on framed paper, 242 x 150 cm) |

|

| Alessandro Cannistrà, Project #15 (08) (2017; smoke on paper, 120 x 120 cm) |

|

| Giuseppe Adamo, Sulcus 2 (2016; acrylic on canvas, 100 x 80 cm) |

|

| Mario Consiglio, POETS (2018; enamel and vinavil on PVC, 140 x 400 cm) |

|

| Marco Neri, Gardens (Israel) (2010; acrylic on linen, 80 x 100 cm) |

|

| Gioacchino Pontrelli, Untitled (2003; mixed media on canvas, 200 x 240 cm) |

|

| Thomas Braida, Clangori (2016; oil on canvas, 215 x 235 cm) |

|

| Gioacchino Pontrelli, Mamma (2016; mixed media on canvas, 380 x 210 cm) |

|

| Marco Neri, Inhabited Center (2015; 35 acrylic elements on paper, 42 x 29 cm each, dimensions variable) |

If De Prospectiva Pingendi is to certify anything, then the first assumption is that painting, repeatedly given up for dead, is as vital a medium as ever. The second, is that the “scenario” on which much of current painting in Italy is moving is that of confrontation with the ancient (a confrontation that, after all, has always distinguished Italian art, even in moments of fiercest rupture: even fractures arise from confrontation), based on the idea that the reading of tradition constitutes a necessary basis for experimentation. The third is that, despite these premises, there seem to be no catalyzing tendencies in Italian painting in the 2000s: according to Mattioli, the only rule that today’s Italian painters have in common is “having grown up with a kind of forced individualism” that has led them “to push their own painting forward, going so far as to repudiate it in some cases and then resume it on a more advanced level.” Super-painting, the curator ventures: erasing in order to affirm. An exhausting reading. But one that can be reasoned about.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.