Following the exhibitions John Constable. Landscapes of the Soul and Turner. Landscapes of Mythology, the Reggia di Venaria concludes the trilogy dedicated to English Romanticism by hosting an exhibition exhibition on William Blake (London, 1757 - 1827), one of the most visionary artists in art history. From October 31, 2024 to February 2, 2025, the Halls of the Arts of the majestic complex on the outskirts of Turin will host Blake and His Age. Journeys in Dreamtime, an exhibition produced in collaboration with the Tate UK, presenting 112 works by the British master to the public. Curated by Alice Insley, an art historian and expert on British art (1730-1850s) at the Tate, the exhibition is a unique opportunity to explore the mystical and symbolic imagery of Blake, an artist whose work was reevaluated and recognized only many years after his death.

The exhibition aims to offer visitors the chance to explore not only Blake’s art but also the cultural and intellectual context in which it developed. The artist is often associated with a mystical approach to reality and a symbolic use of representation, elements that are reflected in the structure of the exhibition, which aims to reconstruct the artist’s entire visionary universe through a narrative of images and symbolic themes.

Thanks to exceptional loans and collaboration with the Tate UK, visitors will be able to see live the nuances of color, iconographic details and symbols that make Blake’s work unique, exploring his deep interest in the Gothic, the supernatural and the spiritual dimension of human existence.

Painter, printmaker, and poet, William Blake was a central figure in English Romantic culture, whose work, imbued with symbolism and mystical references, influenced generations of artists and writers. During his lifetime, Blake remained largely ignored by the public and the cultural elite, but his work is now considered an unprecedented example of visionary expression. The exhibition, designed to bring to life the imagination and energy that pervaded his work, invites visitors on a “dreamtime journey” during a time of great change and conflict, when British art and literature sought new languages of expression.

Blake lived in a time of great social and political transformations, from the American Revolution to the French Revolution, events that profoundly influenced his thinking and creations. The exhibition analyzes these changes through a thematic structure, presenting Blake’s works alongside those of contemporary and later artists inspired by his style and vision. Each section illustrates a key aspect of Blake’s imagery, with evocative titles such as Spells, Fantastic Creatures, Horror and Danger, The Gothic, and Satan and the Underworld.

William Blake is one of Britain’s most celebrated Romantic artists. The extraordinary originality of his art and poetry continues to inspire even today. But he was not alone: many artists embraced the irrational and emotional, tackled highly subjective themes, and sought a renewed spirituality or escape during those decades. Like Blake, they were responding to a world in turmoil. The Romantic imagination that emerged in Britain was born out of humiliating defeat in the American Wars of Independence, the shock waves of the French and Haitian revolutions of the 1790s, the hardships of the long wars with France, years of political and social unrest at home, and the rapid pace of technological and industrial development. The art of Blake and his contemporaries reveals the spirit of their age.

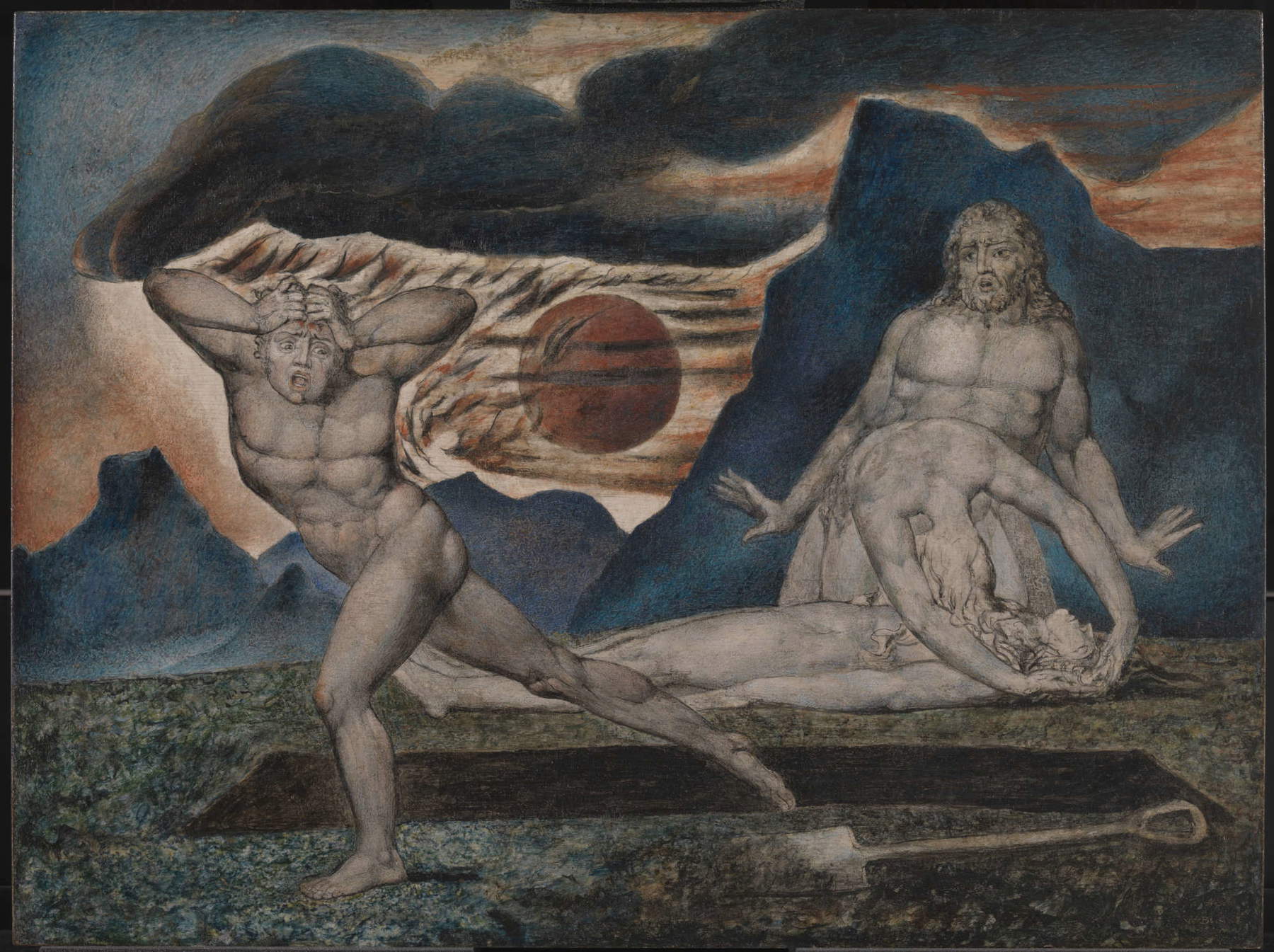

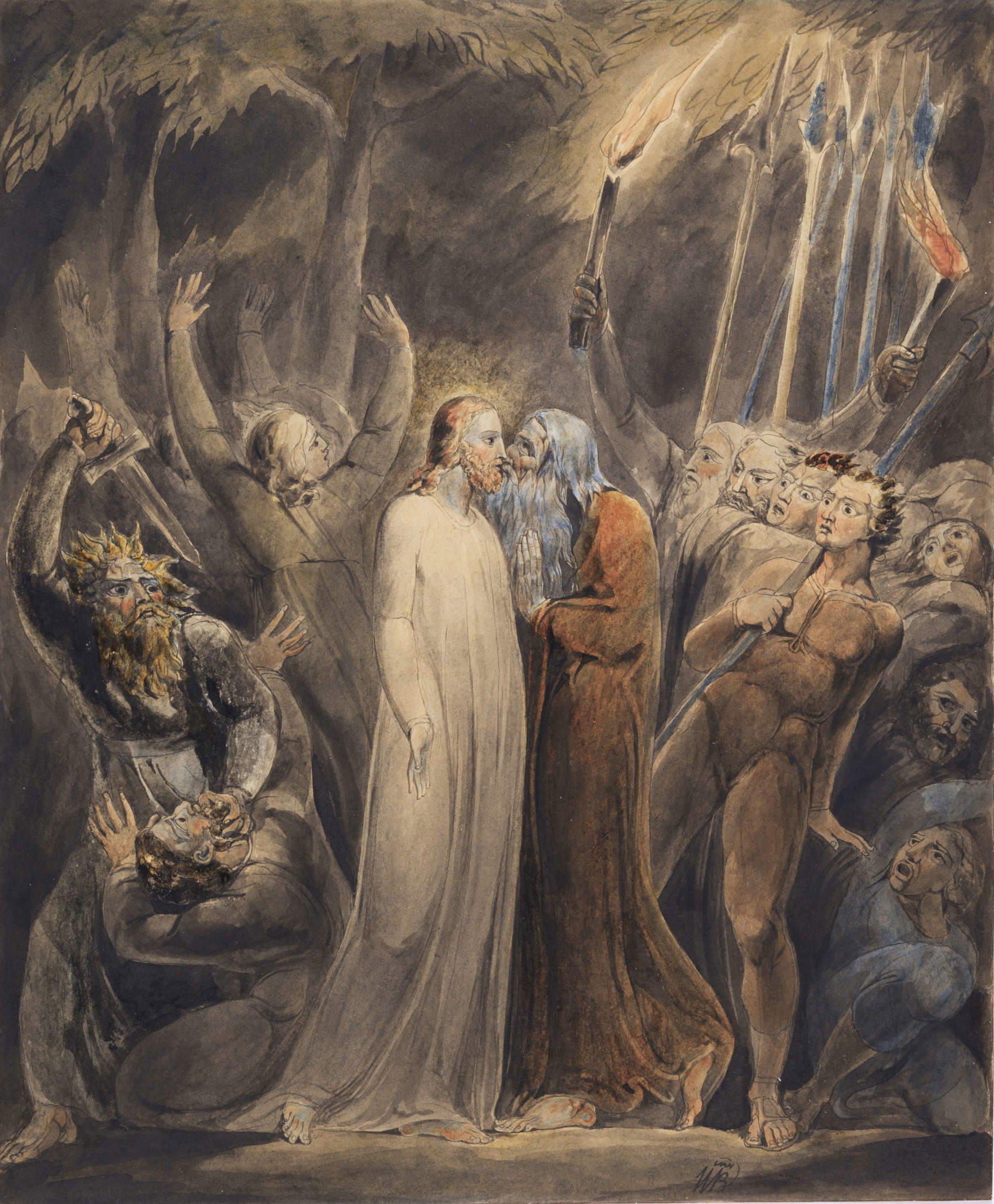

The exhibition opens with the section Horror and Danger. In the face of great change and turmoil, many artists sought to adapt to the profound upheavals in the world around them. This involved embracing the sublime, creating art that could evoke emotions of fear and awe, rather than simply being beautiful. These themes opened up new imaginative possibilities for Romantic artists. They could now depict unsettling, even disturbing subjects, arousing a greater range of emotional resonances. In Blake’s work, this is expressed through contorted and disturbing bodies and the illustration of anguish and torment. The darker themes of imprisonment, madness, horror, danger and illness proliferated among his contemporaries, as did dramatic images of nature. English artists increasingly explored the power and dangers of the natural world, distorting light, proportion, and space to arouse the viewer’s emotions.

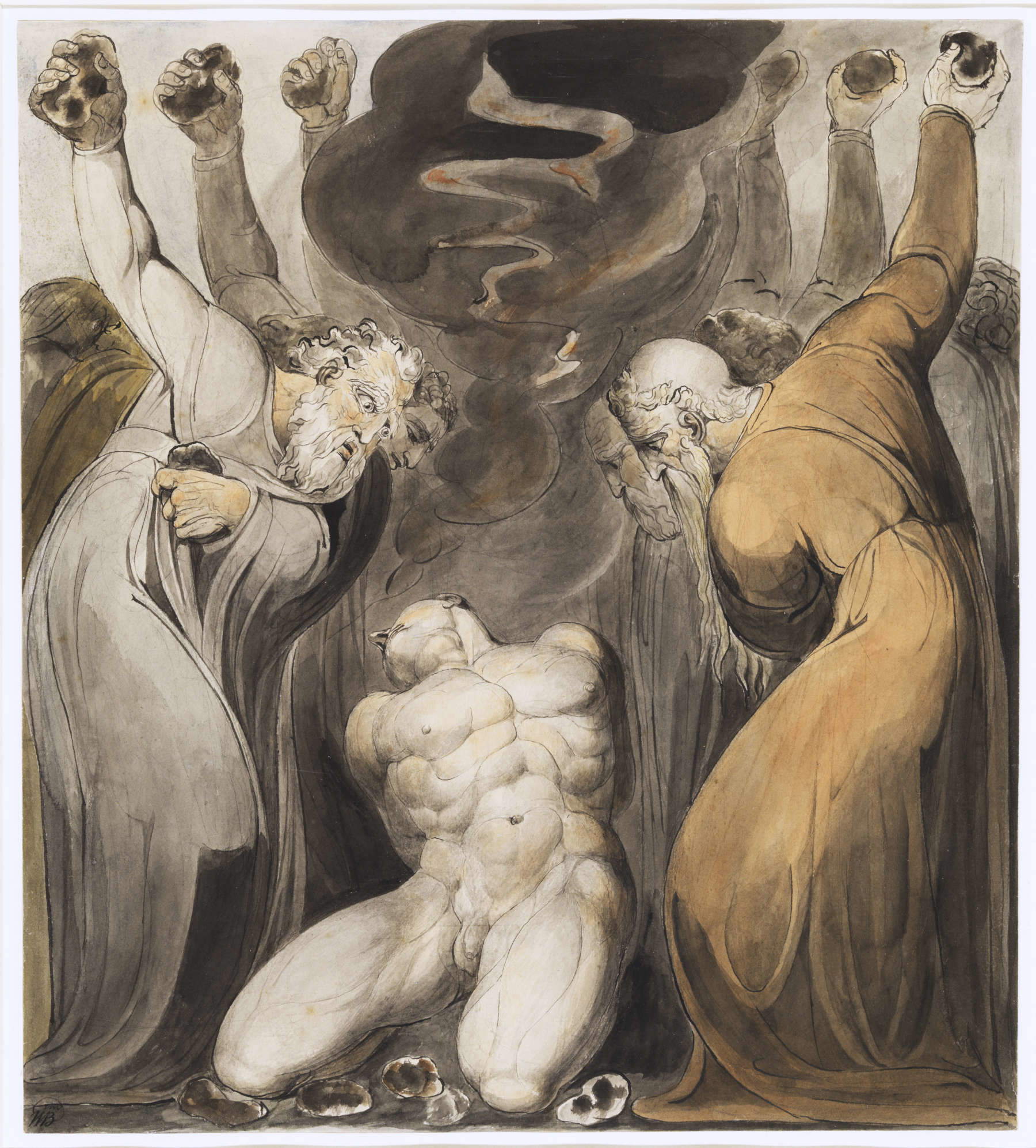

The second section is Fantastic Creatures. Images of the supernatural and the fantastic, the surprising and the monstrous abounded in the late 18th century. These outlandish creatures gave free rein to artists’ imaginations and satisfied the new taste for the shocking and terrifying. In a world where Enlightenment ideals and progress were increasingly challenged, the irrational and otherworldly seemed much more attractive. Blake’s monsters were said to appear to him in visions. Other artists, meanwhile, turned to the apparitions, witches and monsters of literature and folklore, including the creatures of Shakespeare and Greek tragedy. As graphic satire flourished in these years, these fanciful or grotesque creatures acquired a new sharpness, laying bare the vices of contemporary society. It then continues with the Spells section. Although many people regarded fairies and spirits as fiction or superstition, they continued to be present in the visual arts of the time. Artists such as Blake and Heinrich Füssli gave new imaginative life to the realm of fairies and spirits. Their images were often populated by female characters, who appeared in seductive and enchanting ways. Fairies became closely intertwined with fictional women in the art and literature of the time, offering a kind of forbidden pleasure to viewers. Both could be dangerous in their desirability, reflecting contemporary anxieties about female sexuality. They could also represent the imagination itself, suggesting its freedom but also its potentially transformative effect on the subject and the body, for better or worse.

Continuing, the fourth section is Romanticizing the Past: past times were a rich source of inspiration for Blake and his fellow artists. Amid the hardships and tensions of the long wars with France, images and stories from Britain’s past could inspire national pride, provide a sense of escapism, or convey contemporary messages. Celtic and Nordic languages, folklore, art, and architecture gained new appeal. For British artists, the ancient bard took on new strength as a symbol of resistance and defiance. Shakespeare, too, was rediscovered in these years, and his plays allowed a heroic national past to be imagined anew. Even the English countryside, its ruins and churches, became charged with new meaning. Some artists, including Blake, even adopted historical art styles and techniques in an attempt to connect with past eras. The fifth section is entitled The Gothic. Blake’s first real encounter with Gothic art occurred when he was a young apprentice engraver drawing tombs in Westminster Abbey. Over the course of his life, Gothic became central to his artistic vision, representing a spiritual and living art, a timeless ideal. But Blake was not alone. The Middle Ages stimulated the romantic imagination of artists and writers like no other past era. This took many forms, from the close study of Gothic churches to the exploration of the evocative qualities of ancient ruins and castles to the adoption of more linear and precise styles. It could also be interpreted in many ways: for some the Gothic represented a national tradition, for others an oppressive old order, for still others it could express political and imaginative freedom, the possibility of change.

Finally, closing with the section Satan and the Underworld. Artists looked to the past as they imagined the future. The catastrophes and traumas of the 1790s and 1800s, the years of revolution and war, of brutal violence and dreams of freedom, seemed to usher in a new era. What this was like could only be guessed at, arousing both fear of horrors never before seen and hope for transformation and redemption. It was no longer fanciful to believe that biblical prophecies about the end of the world were coming true. Artists gave visual expression to this sense of impending apocalypse, reflecting the anxieties of their time. Blake - who spent the last years of his life depicting the torments of Dante’s circles of hell - was not alone in depicting satanic and infernal subjects. Fate and revelation became something sensational.

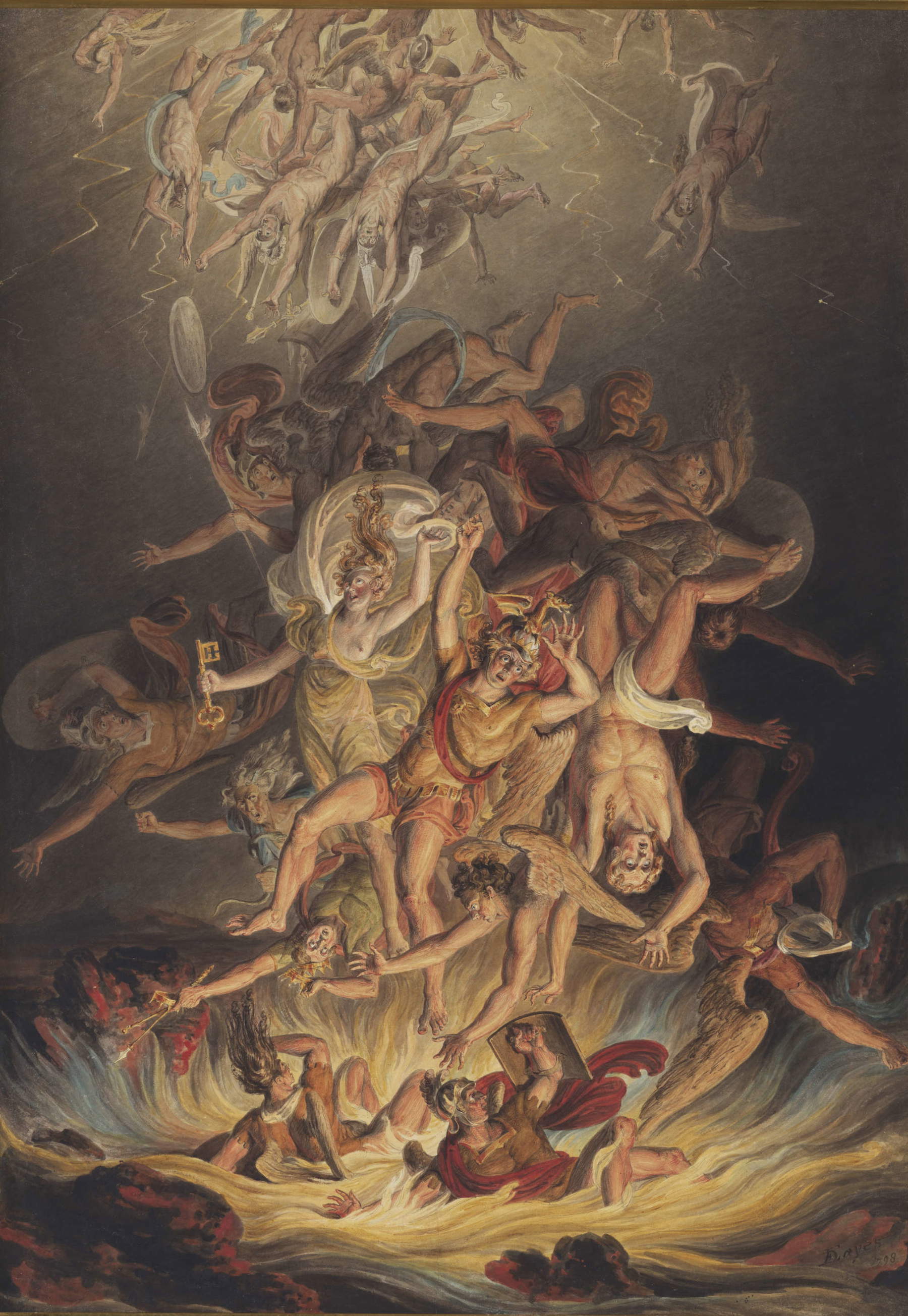

In addition to the two-dimensional works, the exhibition offers a multimedia installation in collaboration with Blinkink and director Sam Gainsborough, an exclusive production for the exhibition at the Reggia di Venaria that projects visitors into Blake’s imaginary universe. This installation, accompanied by Aphex Twin’s electronic soundtrack, enlivens some of the artist’s most iconic works, reproducing on a grand scale paintings such as The Spiritual Form of Pitt Leading Behemoth, a work Blake would have liked to display as a public monument, with dimensions reaching 30 meters in height, as a tribute to the “greatness of the nation.”

Indeed, among the highlights of the exhibition is this visionary painting depicting former prime minister William Pitt as a biblical commander at the center of an apocalyptic scene, an evocative and disturbing image that reflects Blake’s conception of power and patriotism, between devotion to the homeland and criticism of its drifts.

Admission included in the All in a Reggia ticket or with individual exhibition tickets - Full: 12 euros, Reduced: 10 euros (groups of min. 12, max. 25 people and as many as provided by Gratuiti and Ridotti), Reduced children: 6 euros (under 21 -youngsters from 6 to 20 years old- and university students under 26), Schools: 3 euros (minimum classes of 12, maximum 25 students, free admission for 1 accompanying person for every 12 students). Free: children under 6 and those provided by Free Reservation fees on purchase of admission tickets for groups (minimum 12, maximum 25 people): 15 euros per group-7 euros per class.

For more information: lavenaria.it - residenzerealisabaude.com

|

| Blake and his era: an exhibition at the Reggia di Venaria on the visionary dreams of the English master |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.