Five iconic works, four symbolic places, an entire city involved in an artistic experience that blends history, provocation and reflection. This is Seasons, the new exhibition by Maurizio Cattelan (Padua, 1960), one of the most discussed and influential Italian artists on the international scene, who returns to provoke the public with new works. In Bergamo, the Padua-born author builds, with his exhibition scheduled from June 7 to October 26, a diffuse path through the city like a cycle of seasons: not only natural, but also social, political, existential.

From Upper Bergamo to Lower Bergamo, from the Middle Ages to the contemporary, the works on display fit into the urban fabric as interruptions of the usual, as spaces of doubt and possibility. Art, in this project, does not merely decorate but wants to become a critical tool. The seasons of the title are a symbolic pretext: they represent the cyclical nature of life, the changes in society, the flow of history. But behind the metaphor, each work addresses a knot: power, the fall, childhood, memory, exclusion. Everything holds, everything speaks to the viewer.

At theFormer Oratory of St. Wolf, an ancient borderland between life and death, stands Bones, a Michelangelo statuary marble sculpture depicting an eagle lying on the ground, wings spread, as if overcome by a sudden collapse. The eagle, always an emblem of dominance and majesty, is here unmasked in its vulnerability. No longer a symbol of power, but an icon of its crisis.

The choice of marble - the same with which heroes and gods are celebrated - accentuates the paradox: the fall becomes eternal, crystallized. The animal does not die in silence, but imposes the vision of its own failure. Cattelan is inspired by a historical event: the eagle sculpted by Giannino Castiglioni in 1939 for Dalmine, in honor of a Mussolini speech, then removed and relegated first to a summer camp and finally to the company’s own warehouses.

Its parabola - from fascist symbol to naturalist totem, to oblivion - echoes in the artist’s gesture, which captures its essence but strips it of all rhetoric. The “bones” of the title - Bones, precisely - evoke what remains: a structure, perhaps, but also a denunciation. Power reduced to a skeleton and nature, unheeded, presenting the bill.

Instead, at GAMeC - Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art - is Empire, a conceptual sculpture powerful in its essentiality: a terracotta brick, engraved with the word “EMPIRE,” is enclosed in a glass bottle. The contrast between the solidity of the brick and the fragility of the container says it all. Power is here motionless, unexpressed, locked up in itself.

It is an image of stalemate, of powerlessness, of dream (or threat), an image that is never accomplished. The brick evokes construction, the foundation, but the bottle suggests isolation, distance, impossibility. The entire work seems like a message cast toward a future that may never come. The tension is palpable: between what would like to be and what is prevented.

In the interplay between symbols, Empire alludes to the failure of utopias, but also to the paralysis of an age in which the will fails to translate into action. The artist offers no solutions, but hands the viewer an object to interrogate, to decipher. Empire, today, is perhaps just a word without substance, or a bottled-up threat.

Also at GAMeC, No is presented as a variation on the theme of the unspoken, the unshown. It is a reworking of one of Cattelan’s most controversial works, Him (2001), which depicted Adolf Hitler kneeling as if in prayer, his face childlike and disarming. In No, that face is covered by a bag.

The intervention grew out of a censorship request in China for a Cattelan exhibition, but it aspires to become something more: a reflection on visibility, trauma, and removal. The bag is ambivalent: it punishes and protects, obscures and reveals. The identity of the work is denied, but precisely because of this it takes on a new meaning. It is no longer just about Hitler, but about our relationship to the representation of evil.

What does it mean to prevent recognition? Protect the audience or hide the truth? No is meant to be a work capable of disorientation, capable of forcing viewers to come to terms with the limits of memory and the responsibility of the gaze. In an age dominated by images, the act of obscuring becomes more eloquent than showing.

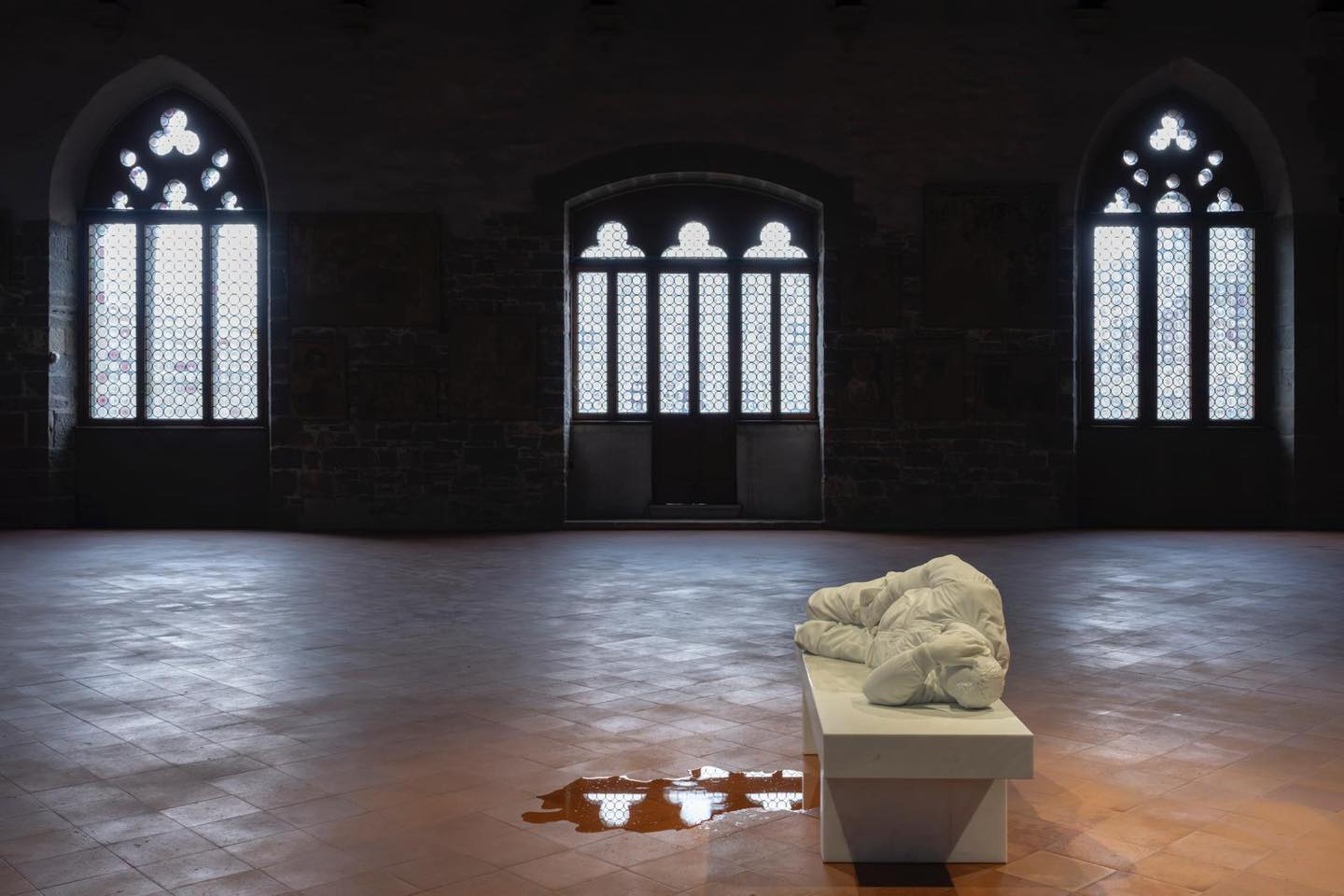

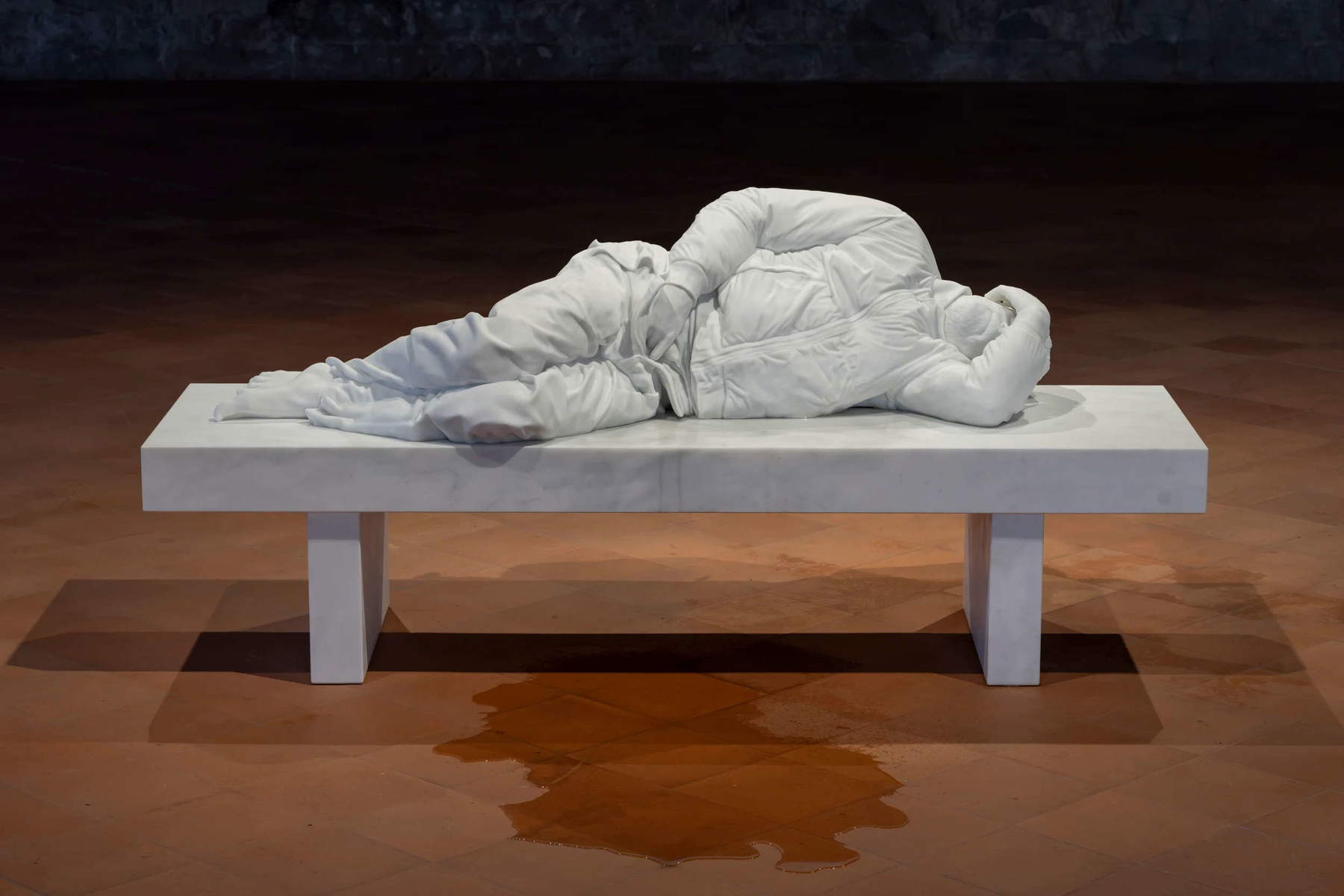

In the heart of Bergamo Alta, at the Palazzo della Ragione, finds space for November, a statuary marble sculpture depicting a homeless man lying on a bench, his pants unbuttoned and a trickle of urine flowing to the ground. The realism is strong, then, but it is the silent dignity of the subject that, in the artist’s intent, should strike.

The man - whose face is that of Lucio, Cattelan’s friend and collaborator - takes center stage in a place that was once the site of civic assemblies and courts. The contrast is violent: who today represents law, society, citizenship? Who is excluded from it? Urine, the ultimate act of corporeality, becomes a gesture of existence, of resistance.

November does not want to elevate the marginal to hero status, but rather intends to show its naked, unmediated reality. The choice to place the work inside Bergamo’s Palazzo della Ragione is also significant: the large Sala delle Capriate, which once housed medieval town assemblies and later became a court under the Republic of Venice, carries the weight of justice, but also of its absence, discrimination and injustice. Short Circuit thus aims to interrogate our relationship with power structures, laws and values that determine who has a right to be in society and who is relegated to the margins because they are deemed “non-compliant.”

Outside, in the Rotonda dei Mille - one of the focal points of Lower Bergamo - stands One, a site-specific installation created with the municipality. Here Cattelan stages a simple and destabilizing gesture: a child on the shoulders of the Garibaldi statue mimes a gun with his fingers.

The gesture is ambiguous: play? Rebellion? Provocation? The title - One - opens to multiple interpretations: is it “one” as an individual, as a new generation, or does it recall the unity of the Thousand? The child breaks into patriotic rhetoric to interrogate it, to destabilize it. Is he a grandson playing with his grandfather, or a vandal challenging his memory?

Cattelan takes no sides, and the work seeks to become a mirror of our relationship with history, with national symbols, with what we inherit and how we transform it. The monument is not only a tribute to the past, but a battleground of the present.

To complement the Seasons project, an urban communication campaign extends beyond the museum spaces. The visual identity of the exhibition invades the city through billboards and site-specific interventions. Of particular relevance is the Kilometro Rosso-the iconic wall designed by Jean Nouvel-where Cattelan has imagined an unprecedented declination of the project.

Here, too, the gesture is twofold: on the one hand, it expands the audience, taking art outside the confines of the institution. On the other, it settles the idea that any urban space can be interrogated by art. The city itself becomes theater, page, provocation, in Cattelan’s style.

|

| Maurizio Cattelan's new provocation: the artist transforms Bergamo with 5 monumental works |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.