Paolo Marini is an Egyptologist whose career is distinguished by the link between academic research and curating international exhibitions. A graduate and Ph.D. in Egyptology from the University of Pisa, Marini has developed an interest in Egyptian grave goods, focusing in particular on ushabti containers, fundamental elements of ancient Egyptian funerary culture. Since 2017, he has served as curator and scientific coordinator of traveling exhibitions at the Egyptian Museum in Turin, where he has conceived and curated major exhibitions, including House of Eternity, which stopped in China and Brazil, and Egypt’s Glory, which was shown in Finland and soon in Canada. He also curated Through their Eyes in Estonia and is preparing a new section on Egyptian writing for the museum. In 2020, he published a popular book on Egyptian deities for the Egyptian Museum, published by Panini. Paolo Marini is also the curator of an exhibition organized by the Egyptian Museum and Villa Bertelli Foundation titled Gli e i doni del Nilo, an exhibition held inside Fortino Leopoldo I in Forte dei Marmi. The exhibition, which can be visited from Aug. 1, 2024 to Feb. 2, 2025, explores the links between ancient Egypt and the Nile River, which was a primary source of life and prosperity for the civilization. In addition to his exhibition activities, he has participated in archaeological missions to several significant locations and since 2019 has been involved in a study mission to Deir el-Medina, under the tutelage of the Egyptian Museum in Turin.

NC. Why Forte dei Marmi for an exhibition on ancient Egypt, organized by the Egyptian Museum of Turin?

PM. The answer could be: why not? The museum has been organizing traveling exhibitions for years and taking them to the most diverse places, beyond the walls of the Egyptian Museum. Italy, in particular, offers many opportunities for these activities, and we seize every opportunity at the drop of a hat. When the Municipality of Forte dei Marmi showed interest in the exhibition, which in a reduced version had already been exhibited in Trentino, they contacted us. We accepted the proposal with enthusiasm, also because we are pleased to move to Tuscany, a region to which we are very close for various reasons. Personally, I studied in Pisa, and the chairman of our scientific committee is a full professor at the University of Pisa, so there is a strong cultural and professional bond with the region.

How important is it for the museum to have collaborations with different Italian foundations, such as that of Villa Bertelli in Versilia?

For us it is very important for several reasons. The first has to do with enhancing the value of our collection: the Egyptian Museum welcomes a large pool of visitors, with more than a million admissions recorded last year alone. Nevertheless, we are aware that this represents only a privileged segment of the public, people who have the opportunity to travel and reach Turin, a city that remains slightly off the traditional Italian tourist circuits. Therefore, when we have the opportunity to move and bring testimonies of our collection to other cities, thanks to the support of local institutions, we consider it fundamental. This allows us to enhance our heritage and strengthen the brand of the Egyptian Museum, which also operates in a commercial dimension. The success of these initiatives helps fund research and support our cultural mission, and this is important because it shows how culture and economy can complement and support each other.

What does the exhibition’s central theme address?

The exhibition is developed on several registers. The first is aimed at everyone: both those who know ancient Egypt and Egyptology well, or at least in part, and those who have only scholastic reminiscences and wish to approach this fascinating world for the first time. On the one hand, we recount the main aspects of ancient Egyptian civilization, and on the other hand, we focus on a crucial topic, namely the art, craftsmanship and production of material culture. This is the element we invest most in, as it is the key to obtaining the most relevant information from ancient civilizations, such as the Egyptian one. In the exhibition, we have therefore chosen to make material culture dialogue with visitors and develop a focus on the work of master craftsmen, the same ones who helped build the collective imagination about ancient Egypt.

How was the exhibition layout thought out in relation to the architecture of Fortino Leopoldo?

We visited the exhibition spaces and understood what were the key aspects to make the most of those places. Starting from this analysis, we decided which objects to display, selecting those most pertinent to the exhibition concept, thought out and defined beforehand. This method also influenced the choices regarding the size of the objects. Another aspect we considered was the connection with the social fabric of Forte dei Marmi and the surrounding area, particularly the world of crafts and manual labor, such as quarries and marble work. The environment of Forte dei Marmi is closely linked to the Tuscan artistic tradition, just think of figures such as Michelangelo. This connection guided the selection of the pieces. We also tried to bring in objects from our warehouses, thus giving residents and visitors a chance to see previously unseen finds. Some of these objects have already been displayed on other occasions, while others are being shown for the first time in this exhibition. The variety of exhibits selected allowed us to represent different eras of ancient Egypt, with objects belonging to different historical periods. This allowed us to illustrate various artistic techniques, distinct styles results, religious conceptions, funerary customs and daily routines. The dialogue with the exhibits allowed for an in-depth and multifaceted understanding of Egyptian civilization.

The exhibition offers a journey that covers more than 3,000 years of history and ranges from the Predynastic Era to the Greco-Roman period. How was the complexity of this time span (and also cultural) addressed in the selection and presentation of artifacts such as the canopic jars, amulets, or the statue of the goddess Isis?

Since this is such a broad period and such a complex civilization, we could not address all the salient issues that would allow a visitor to understand, even superficially, the complexity of Egyptian civilization. That is why we chose to focus on one specific topic: crafts. Our choice was to talk about the long historical span that characterized Egypt, from the predynastic eras to the merger with other cultures, focusing on the reflections in the artistic and technical spheres. In fact, when we talk about the making of sculpture, painting, bas-reliefs or even mummification, we are talking about techniques that, while remaining similar, differ across historical periods. Each technique tells us about a specific aspect of Egypt, related to the cultural and temporal context of each period.

In your opinion, what is the most relevant find, fundamental to the understanding of the exhibition and the Egyptian world presented in Forte dei Marmi?

The symbol of the exhibition that we chose is the Greco-Roman Epoch mask also visible in the poster that was the focus of the promotional activity. It is an aesthetically fascinating artifact that can attract the attention of visitors, but its choice goes beyond its beauty; in fact, it embodies all the concepts we wanted to explore in the exhibition. It is a mask made of cartonnage, a material specially created by the Egyptians. Cartonnage responded to an economic-social need in Egyptian culture: to make an object, considered fundamental from a ritual and religious point of view, using cheaper materials. This product saw its diffusion in a period of social and economic crisis, representing an appropriate response. The social and economic concept, combined with artistic validity and symbolic and ritual value, emerges in both the funerary and religious spheres.

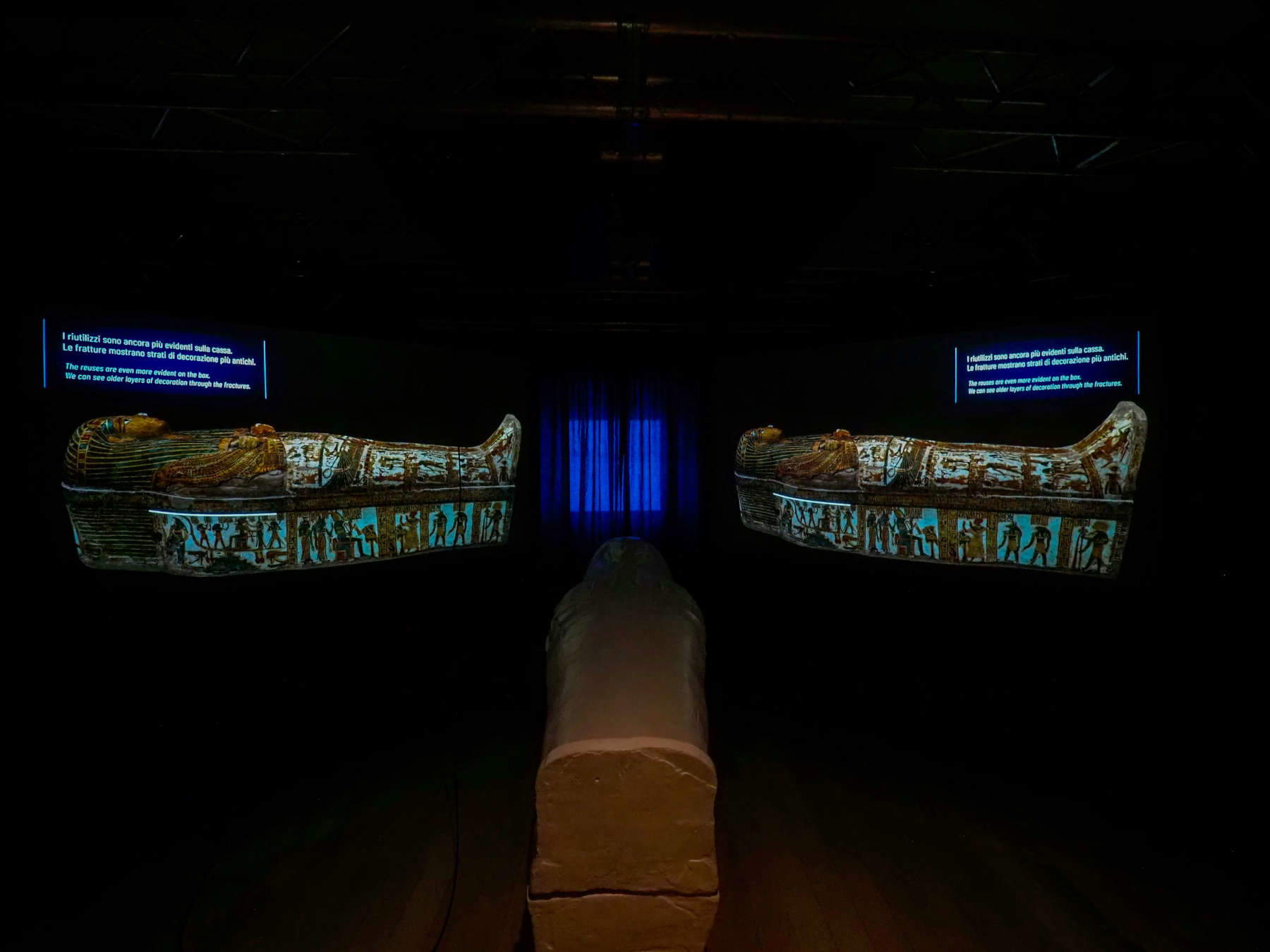

The video reproduction projected on the Butehamon sarcophagus made with 3D and mapping technologies represents a strong link between archaeology and new art technologies. In your opinion, how does this union succeed in changing the way visitors can interact with archaeological artifacts?

These solutions allow us to make topics that are often complex and difficult to understand accessible. The replica of the Butehamon sarcophagus, in particular, gave us the opportunity to symbolically bring to Forte dei Marmi an artifact that, partly due to conservation constraints, cannot be moved from the Egyptian Museum. Although we could not relocate the original object, we found a way to make it move conceptually. This is not a replica as an end in itself, thus trivial or kitschy, nor is it a reproduction that distorts the image of the original, but an installation that tells the story of the making of the original work. Thanks to the use of video mapping, visitors can follow the entire complex production process: from the assembly of the wooden planks to the laying of the preparatory stucco, from the drawing of the sinopites to the sampling of the various parts, to the final painting that characterizes the sarcophagi of that period with the typical yellow color. All this is told through compelling and innovative technology. At the end of the experience, visitors feel excited and gain a range of knowledge that they might not otherwise have obtained.

Speaking of new technologies, why was it decided to place, outside the Fortress, the reproduction of the Colossus of Ramses II made through 3D photogrammetry and milling?

The exhibition begins with a reflection on the birth of Egyptology and the history of ancient Egyptian art. The statue of Ramses II, the original we are hosting here in Turin, is closely related to this historical period. The find arrived in Turin in 1824 and was immediately noticed by Jean-François Champollion, believed to be the founder of modern Egyptology, who had just deciphered hieroglyphics. Champollion, observing the statue, which was still fragmentary at the time, sensed that it must be an extraordinary work and immediately asked the director of the then Egyptian Museum in Turin to restore it. At that time, Egyptian art was not yet as highly appreciated as it is today, and we are talking about the era just after Winckelmann’s theoretical studies of ancient art. We developed this reflection in the very first part of the exhibition, enriching it with the creation of a 3D model. The model, like that of the Butehamon replica on the second floor, made it possible to symbolically bring the original to Forte dei Marmi, despite the fact that it was an immovable object. Corresponding to this 3D digital model, a fiberglass replica of the statue of Rameses II was placed outside, in 2:1 size. The replica actually has a promotional purpose as well: to draw visitors’ attention and invite them to discover the wonders of the exhibition.

The director of the Turin Museum, Christian Greco, pointed out that Egyptian funerary culture is often misrepresented, arguing that the ancient Egyptians did not have a fixation on death, but rather a great respect for the passage into the afterlife. How is this aspect presented in the exhibition? How can the exhibition introduce the more human side of the people who gave life to the objects on display?

Egyptian civilization is one of the longest in the history of the ancient world, and this is partly because of the attachment this people had to life. Unfortunately, we tend to lose sight of this today, as Egyptian archaeological remains are mainly about the funerary context. But this is due to a technological choice, which favored the use of materials that were durable for funerary works and perishable for the domestic sphere. Indeed, the texts tell us that the real priority of the ancient Egyptians was life, not death. Many of the objects in the exhibition, in fact, come from funerary contexts. Nevertheless, we often try to interrogate them about everyday life. A practical example is found in the first room, where two wooden models are displayed: one represents a boat, the other a craft scene of bread and beer production. Both are from funerary contexts, but they speak of everyday, working activities, such as sailing, baking, and brewing. In general, most of the objects on display tell us about daily work and manual activities. Studying them allows us to get closer to the people who made them. The funerary aspect I mentioned earlier is obviously not neglected also because it allows us to get closer to religious beliefs. It is important to understand that our approach to the collection is always geared toward the question: what was this object used for? Who produced it? When? Here, this allows us to explore the Egyptian civilization in its true complexity and to talk not only about mummification and death, but also and especially about life and technological evolution over the millennia.

Photogrammetry, mapping and 3-D reconstructions are discussed. What new uses of new technologies is the Egyptian Museum of Turin adopting, particularly with the latest exhibit Materia. Form of Time presented on October 5? What plans do you have for the future?

Matter. Form of Time puts archaeometry (the science that studies archaeological materials with laboratory analysis ed.) at the center of its narrative, which is the backbone of the Egyptian Museum’s research, conducted for several years now. Particularly since 2015, when Dr. Christian Greco became director of the museum, archaeometry has become one of the fundamental tools for interrogating objects. As a museum, we have a double obligation to these artifacts: we must study them, listen to what they can tell us, and also enhance them and preserve their original state. Our commitment drives us toward the use of advanced technology and science that not only protects the objects, but also restores them and presents them to the public in the best possible way. In particular, within the room Matter. Form of Time, we have gathered all our knowledge about the different materials and technologies that accompanied the making of these artifacts. Our intention is to make people also appreciate this scientific aspect, which often straddles the technical and historical sciences, while at the same time presenting some of the issues related to conservation and storage management. A concrete example of this approach can be found in the second room of Matter. Form of Time, which becomes a large warehouse housing more than 5,000 vases. In this project, we transferred vases from warehouses not accessible to visitors and made them available to the public. This allows us to monitor an extraordinary collection while also enhancing objects that would otherwise remain unknown to most visitors. It is just one part of a process we undertook a few years ago and are continuing this year, on the occasion of the museum’s bicentennial, with the creation of new rooms. Future plans include the roofing of the museum’s courtyard, which will allow us to expand the exhibition space, and the free use of the Temple of Ellesiya, an important acquisition donated by Egypt several years ago, but until now only open to visitors upon payment of a ticket. In addition, we are preparing a room dedicated to Immersive Egypt, with the intention of recreating a context that recreates the original environments from which the exhibits came. The project aims to give visitors back an experience closer to the historical and environmental reality in which these objects were used. In this way we give a new dimension to the understanding of Egyptian heritage.

The author of this article: Noemi Capoccia

Originaria di Lecce, classe 1995, ha conseguito la laurea presso l'Accademia di Belle Arti di Carrara nel 2021. Le sue passioni sono l'arte antica e l'archeologia. Dal 2024 lavora in Finestre sull'Arte.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.