Studio d’Arte Raffaelli, a historic contemporary art gallery in Trento, recently turned 40 years old: it was founded in 1984 by Giordano Raffaelli, who still leads the gallery that has become over time an important point of reference for art lovers, especially for African art, American art of the 1980s and Italian figurative art from the Transavanguardia onward. Focusing on painting, with forays into photography and sculpture as well, Studio Raffaelli has distinguished itself over the years for being the first Italian gallery to organize an exhibition of an African artist, for launching in Italy artists from 1980s New York such as Donald Baechler, Ross Bleckner, Philip Taaffe, Peter Schuyff and others, and for its long collaborations with African artists, starting with Zanele Muholi, who was launched in Italy by the Trento-based gallery. On the occasion of this important milestone, we caught up with Giordano Raffaelli to get some background on the gallery’s history, his research, and also to talk briefly about the current situation of young Italian contemporary art. The interview is by Federico Giannini.

FG. Your gallery was opened in 1984, so it has recently turned 40 years old. In fact, however, we know that you have been working in the contemporary art sector long before that date...would you like to tell us about your beginnings as an art dealer and gallery owner?

GR. The first input I had toward this work was when I was a young boy: my father knew an Istrian artist who had been displaced here in Trentino after the war (Romano Conversano, an artist from the group of Migneco, Guttuso and the figurative artists in their circle). They had met right here in Trentino after the war was over. Then, in the 1950s, Conversano had bought the castle in Peschici, on top of the fortress, overlooking the sea: he invited us several times in the summer as his guests, and there I would see cars arriving from Milan with certain characters who would take his paintings, haggle, then wrap them in blankets and leave for Milan. I had been fascinated by the stories of these people who would take a two-day trip to pick up two or three paintings and then return and sell them in Milan. There, that’s where I got my first input toward working as an art dealer. Then in the early period of my career I was lucky enough to meet a couple of important people in the art world. The first one was a collector, Carlo Cattelani, a farmer from Modena who lived in a cottage in the country and hosted a lot of important artists in his house and bought their works. He was the first to deal with Salvo, Montesano, De Dominicis, Nitsch, the whole Fluxus group and many others. With the good fortune of having this knowledge and getting into his sympathies I was able to get into the business that mattered a little bit, because then from Trento it was not easy at all. The second was Luciano Pistoi, whom I met through Cattelani and with whom I collaborated several times over the years for his event that he was doing at Castello di Volpaia. From there the history of my gallery then began.

What are the main lines of research that guided the gallery in those years and that guide it now?

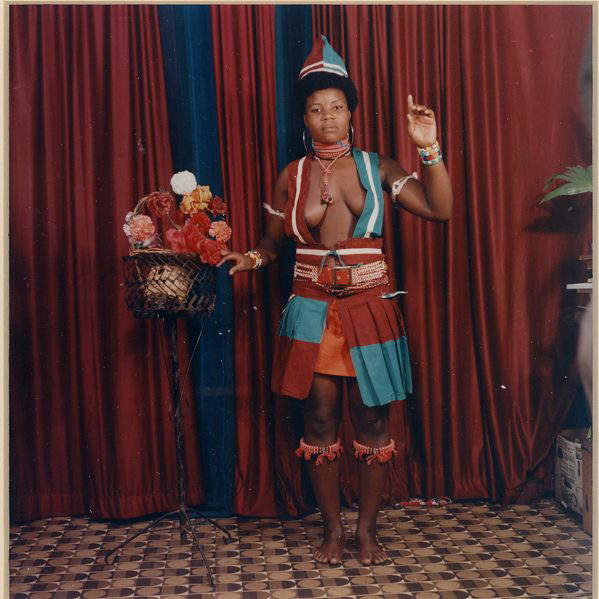

Only one: that of painting. A painting with, perhaps, sometimes some openings of conceptual origin, but we deal with painting, even when we look for young people. It happens that there can also be photography, but always where there is a pictorial image. In photography, for example, we dealt first with African artists of the 1960s and 1970s, such as Malick Sidibé, Seydou Keïta, Jane Alexander, and many others who were practicing that kind of photography where there are no references to Western painting, but there is a search for their own traditions, their own origins.

After all, when reconstructing the history of Studio Raffaelli, everyone points out that you were the first Italian gallery owner to have organized an exhibition of an African artist: it was, if I remember correctly, 1991 and you had brought Chéri Samba to Italy for the first time. Today African art has become a kind of fashion, but in those years what did it mean to work with Africa and African artists?

Not everyone remembers, before 1989, and particularly before the Magiciens de la Terre exhibition done at the Pompidou in Paris, contemporary art was practically only Western: there was no Chinese art, no Oriental art, and no African art of any kind. With the explosion of that exhibition, attention shifted to other continents as well. I took the ball and met Chéri Samba’s dealer in Paris and with him organized the first exhibition, partly thanks to the push of my wife who was enthusiastic about this artist. Exhibition that was difficult, because paintings were expensive even then, and for the first six months we didn’t sell anything, so I had to buy all the paintings in the exhibition myself. But then I still had a great satisfaction, because a Canadian museum and a Japanese museum bought me two paintings each, and from that episode the luck began to turn.

Then there is another important strand, which is American art, because you have worked and continue to work with important artists in 1980s New York, such as Baechler, Taaffe, Schuyff and many others. What kind of art was and still is your gallery looking for in America?

The art that I felt the most. Which was the disruptive art in those years, which was the 1980s. And then kind of all the students of that movement... which then did not exist as a movement per se, like, for example, a Transavantgarde. There was, however, a common feeling that traveled through the world of art, literature, music in New York in those years. Unfortunately, I was not able to contact the two who later became perhaps the most important, which were Keith Haring and Basquiat-I was a couple of years off, because then, later on, I became very good friends with Annina Nosei, and we then collaborated with her several times. I would buy her artists and do exhibitions of her artists, and she would follow my lead, doing exhibitions of Montesano, Galliano and other Italian artists that I was dealing with at the time. Then I also worked with artists who were students of Donald Baechler, like Brian Belott, Taylor McKimens and others who knew the art of that period well and followed that kind of feeling by renewing it.

In the catalog of an exhibition that your gallery hosted a few years ago (9 New York of 2018), in a conversation with Alan Jones, you said that your approach toward these artists is that of the editor who follows the author book by book. So you basically took these artists who were young and followed them until they became established, until they became masters, basically.

Yes, and I would like to say that I followed them through thick and thin, because even in difficult times I always tried to support them, even financially when they were maybe struggling. If I fall in love with an artist, then I like to follow them forever.

And today there are not many gallery owners who think like that.

No, in fact I also tend to say that the nicest compliment I was given by an artist was to say that I am an “old style gallerist.” It made me happy. Because I think that’s right. We are not corned beef vendors: we sell art, so we have to try to behave in a certain way.

Do you continue to look for young artists today, or do you prefer to follow artists who have established themselves over time along with the gallery?

We try to follow both lines: even now we are leaving for New York and we are organizing an exhibition, for October, of a young 35-year-old American artist who is not known in Italy. It’s going to be a really interesting exhibition: he is an artist of Hungarian origin and he makes small paintings that represent the reality that you find in the streets of New York, in theaters in New York, in cinemas in New York. At the same time an exhibition will be done by his brother, who is a photographer, and he photographs the same situations. It is interesting to know that his grandfather was a prominent Hungarian painter, very famous, who at some point in his career turned from a painter into a photographer. In fact, there are photographs of him, for example, capturing Franz Liszt playing on the piano and other such situations. It’s interesting to see how the two grandsons have dedicated one to the art of painting and the other to the art of photography, and how this family that was involved in the world in the culture of the Austro-Hungarian Empire goes on through the years and with good results. It will be a very good exhibition, in my opinion.

Since then Studio Raffaelli also continues to try to discover new young people, I ask you how do you recognize an artist, a talented young person, in your opinion. Since, you said, you fall in love with artists, what is the spark that triggers this falling in love?

For me it is instinct. For others it may be study, research ... for me, I repeat, it is instinct: it only takes me a few seconds when I see an artist for the first time. And if in those five seconds something clicks fine, otherwise it is difficult that in two months, seeing the same things again, I will fall in love.

An emotional approach then.

Yes. Only emotional. Definitely.

Earlier we mentioned Annina Nosei and your collaboration: here, when Annina Nosei was bringing Transavanguardia to America, you were bringing American artists to Italy. How did you work together?

When I would go to New York I would go and find out the latest exhibitions she had done, she would also show me things left over from previous exhibitions, and if I liked an artist, then we would organize the exhibition at my place. For example, we did an exhibition of Jenny Watson, who had the whole Australia Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 1993: Annina Nosei had done more exhibitions with her. After that I would propose to her some Italian artists that I thought she might be interested in. I always remember the trip I took with Montesano in the summer to Ansedonia to Annina Nosei’s house, and when I introduced him to her she was thrilled, in fact she then did two exhibitions of her own. It was a collaboration of knowledge that we exchanged to do new things, to invent new things and to promote new artists.

We are of course talking about thirty, forty years ago. Today, however, is there still, in your opinion, this exchange relationship between Italian and American gallery owners or has it been lost over time?

It has been lost, certainly, because with the big galleries today it is impossible to talk, to have a personal relationship. I knew Barbara Gladstone well but she passed away a year ago. With the gallerists of the new generation it is difficult to have a dialogue because now in the United States there is another system of work. There is another system of life. So it is more complicated. But just recently I promised myself, even with my daughter Virginia who is now working with me in the gallery, to re-establish relationships with some galleries, to try maybe to promote our artists in the United States and to promote their artists to us. For a while maybe I kind of let it go a little bit myself but, as I said, I promised myself to try again, although it is not easy, because there are other dynamics than there used to be.

And what has changed for the worse since the 1980s?

We’re dealing with multinational corporations: I’m referring to the big galleries that do a bit of the heavy lifting in the art world. Getting to work with them is virtually impossible. It is difficult to even be able to contact them.

So, of course, this situation has also caused some damage to Italian art, in the sense that Italian art today is no longer able to establish itself in America as it used to be able to.

Yes, also because to establish yourself in America you have to live there. There is nothing to do. And here in Italy, it’s not like there are many young artists who are willing to hustle as much. It takes grit to make your way in a city where there are maybe ten thousand artists and two thousand galleries, and it’s not easy. It really takes tremendous strength, and there are not many artists right now, in my opinion, who can get it.

Anyway, speaking of Italian artists, you have several working with Studio Raffaelli. Willy Verginer’s exhibition closed a few hours ago, for example, but your gallery also works with younger artists. On the basis of what do you choose Italian artists? And how do you think Italian art is today?

On Italian artists my son Davide works mainly, and he collaborates with several young Italian artists. There are many good ones, but in my opinion the one who has the cue, the one who can go all the way is missing. In Italy today there are many good artists, but the champion is missing. It applies to so many other fields, in sports for example, where there is a very high average of very good athletes, but there is a lack of a great champion. The only exception perhaps is our Jannik Sinner, the only one who can be compared to the champions of yesteryear. Even in painting in Italy there are many good authors, many good painters, however, the one who has the extra shot is missing. But maybe that’s the way the world is today. Even in music I find it hard to think of today’s Beatles or today’s Rolling Stones.

You mentioned Your son, Davide, who in collaboration with Camilla Nacci Zanetti opened the Cellar Contemporary gallery that promotes, precisely, the work of young Italians and internationals. And of course he collaborates with you. What is it like working with your son?

I get along well. With both my sons I have a very good collaborative relationship. There are then of course struggles and discussions, but now Davide has been running his gallery for almost eight years and we always collaborate well together, the relationship between the two galleries is very open and very collaborative. Recently, for example, he participated in a fair in South Africa with his gallery, however he also brought some of our stuff.

What do you have the most heated discussions about?

Not on the choice of artists: we almost always agree on that. Equally on work choices. Instead, we find ourselves arguing about the ... little everyday things.

Going back to what you said at the beginning, that Studio Raffaelli has always worked with painting: it follows that you do not look at art forms such as large-scale installations, video art and so on. Here, why this choice to focus only on painting and sculpture?

Because what gives me emotion is mainly painting. And then painting is the art form that I think I understand best. Just that. Then I also believe that a gallery owner cannot become an all-rounder and do everything. I have tried to specialize in this field as best as I can and I have gone on that way. With some forays on photography as well, but only on photography of a certain kind.

And then, I mean: it’s a field that has given you so much satisfaction....

Yes, of course. Even on African painting there would really be a chapter to open. And then let’s not talk about African photography, the same thing applies, because the studio photographers of the 1960s-1980s were so many, there were not only Malick Sidibé, Bob Bobson or Seydou Keïta, there were so many others, but you would need a gallery that does only this kind of work. And it would find beautiful things: I’m thinking for example of Sanlé Sory, so many photographers that nobody here knows about, and who are really very good.

Was it easy to propose at the time to the Italian public, to Italian collectors, to Italian buyers this kind of art, or was it not immediate?

I can say that the response in some cases has been striking: when we did the first exhibition of Bob Bobson, a studio photographer, the only one then who did color photos (we presented him at an edition of Miart), we got an extraordinary press response, without, for that matter, having moved in any way. I would say the largest press response we ever had in our career. And then also a very important high-level audience response. Even when we did, in the early 2000s, Zanele Muholi’s exhibition (the first exhibition in Italy), she was an absolutely unknown artist, but even then we had a fairly good response. Even here in the province, from collectors in Trent. Collectors in Trento who then later, moreover, also had some satisfaction from the economic point of view, because the quotations of Zanele Muholi, compared to that first exhibition that we did on the occasion of the edition of Manifesta that was held that year here in Trento, today have increased tenfold.

Today, however, Zanele Muholi is known to everyone. In short, it is you who brought her to Italy and made her known.

Yes, I was the first to do an exhibition in Italy of Zanele Muholi: it was a small exhibition with twenty photographs of Zanele Muholi, which at that time nobody knew about. I was able to do it having frequented South Africa a lot: I had seen her work in the gallery that treated her in Campo City, and I bought that twenty or so photos with which we then did the exhibition. It was also a risk.

Speaking of which, since you open the topic for me: has your appetite for risk over the years increased, remained stable, decreased? Also, do you think gallery owners today are still as risk-averse as you might have been at the time?

I have to say actually that I was not one who took a lot of risks: there are gallery owners of my age and generation who really jumped through hoops and took huge risks. Today I don’t see so many of them, they’re all kind of trying to play it safe, to live on. In the gallerists of the new generation I don’t see the big personality: I see a lot of very good gallerists but they work homogeneously, each one carrying on their five or six artists. I don’t know how to put it: let’s say that today I don’t see a gallerist like Sperone, that’s it. It’s kind of like we said before for artists. For both artists and gallerists we have come to a leveling off of quality, which quantitatively is much higher, in the sense that there are many more good artists and gallerists than there used to be, but qualitatively there is a lack of leading figures. This is what I could also see at the various fairs, where you have a hard time seeing any really interesting young artists.

To conclude: one of the singularities of your gallery lies in the fact that you often invite artists to stay in Trentino. Almost all the artists who collaborate with you have passed right through Trento physically. Why do you consider this contact of the artists with the territory in which You work important?

Meanwhile, because in this way they can sometimes also be inspired by some theme that they can only develop by staying here for some time, or they can assimilate aspects of the city and the territory that they can then bring into their works. I remember one of Ontani’s first exhibitions, Trentazioni was the title: he made a series of paintings inspired by the geographical situation, the mountains, everything he could find here. The last one was Melissa Brown, who came here a year ago, visited the Castello del Buonconsiglio, focused on some objects that she then silk-screened on the backgrounds of her paintings. So I think it’s interesting to have artists work in Trento, as it’s also an interesting city historically and artistically. It is interesting to have them live a period here and afterwards establish a relationship that can also be made explicit in a relationship that is daily for at least a certain period, and then remains so forever. I’m talking about human relationship and artistic relationship.

And I imagine that artists will be excited to work in Trent when they come!

Yes, especially the Americans, but the Italian artists have always been happy too. And they feel a bit like family. They have told us that. Several times they really said, “We feel like family.” We work really well, in short. So you try to establish a friendship that can then last over time. Of course, it can also be interrupted for years, but it always remains a fairly deep acquaintance that cannot be forgotten.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.