The exhibition that opened in Pisa, at the Palazzo dell’Opera del Duomo, last June 15, represents in some respects a methodological bet, or if we want, a tautology. If in fact there is a building that does not wait to be shown, because it is even exhibited to the sight of the numerous tourists who trample the grass of the so-called Piazza dei Miracoli, this is precisely the bell tower of the Pisa Cathedral. A direct perception of the architecture, which of course is overpowered by those mediated, and made indirect, by illustrations in newspapers, websites, and in comic books. Years ago, a not at all rough calculation specified that the Leaning Tower is among the most popular and most searched monuments on the web, just below the Colosseum.

What is more, the Campanile is singularly bare of hidden works of art, of those unknown treasures concealed by the darkness of the stairways and sacristies, as is so often the case in palaces and churches. Even the albeit numerous column capitals, all skillfully carved (the Tower as a “column made of columns,” someone called it), would risk disappointing the most discerning palates, for they are now the result of replacements that began very early, and ended in the 19th century, when skilled craftsmen removed the last capitals that were now damaged, to replace them with copies, sometimes faithful, usually the result of generous reinterpretations (but those few survivors, by Biduino, are present in the exhibition).

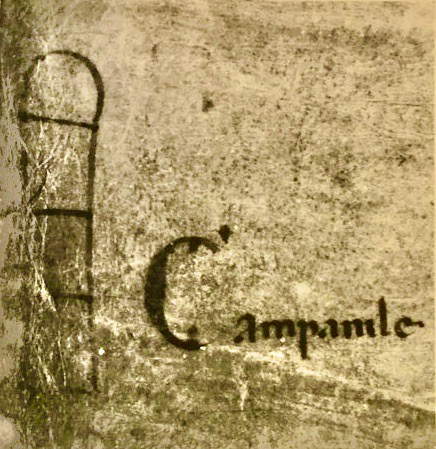

The theme we worked on was therefore indirect, that is, relating not so much to the Tower itself (although this is a theme nevertheless addressed, as we shall see), but on how it was perceived and represented. A path that starts from the first certain image of the monument, constituted by a drawing in a parchment where the Tower was distinctly represented at the height in which its first architect left it in the 12th century, confirming how the interruption of the works was authentic and perhaps interpreted as definitive, since the Tower was provided with a wide cover. Pivot, moreover, from which the exhibition takes its starting point, because it is precisely to the fascinating question of the Tower’s autography, recently returned by Giulia Ammannati to Bonanno Pisano, that the same professor of the Scuola Normale Superiore devotes a section.

Should we wish to scrutinize the depictions of the Tower from its beginnings, we would find, and the exhibition obviously seeks to account for this, that from the 14th century onward (that is, from when the Tower was completed) for a long time it was virtually impossible to find the Tower depicted in isolation, being illustrated, if anything, in two distinct but contiguous ways. Soaring and dominating the city, to the point of becoming its most recognizable element; leaning but alongside the Cathedral, to remind us of its essentially religious function. This is the case in the extraordinary panel with Saint Nicholas of Tolentino saving Pisa from the plague; or also in the minute but fundamental engraving by an unknown artist from the early 16th century, where the city shows the towers devastated by the Florentines in 1509, but with the Tower well in evidence in the center, documenting with its unscathed profile its almost symbolic value. So too in Giorgio Vasari’s drawing for Palazzo Vecchio’s Taking of Pisa, with the Tower as a formidable descriptive element of the city.

A beautiful 1603 canvas by the Sienese artist Ventura Salimbeni, theAllegory of Pisa, also shows us a rorid woman, her face misted with a veil of restrained sadness, intent on nursing her children, while the ’inertia of the weapons laid at her feet shows how that newfound wealth was the fruit of Peace, and that woman clothed in the robes and motions of the Christian virtue of Charity, was none other than Pisa, finally able to feed its citizens, thanks to the generosity of those who had persuaded her to lay down her arms. For in the background, but in evidence, the Tower and the Cathedral, and the Vase of Talent, constituted a decisive reading suggestion.

Even at the turn of the century, this persistence of a Tower that, like a rhetorical figure, alludes to the whole, was well adopted by a Florentine painter who in his younger years very often walked the streets of Pisa: Benedetto Luti. The exhibition features a beautiful early canvas by the Florentine painter, thought to be lost and only a few years ago rediscovered in an important private collection, an interpreter of the abstract pro-Pisan intellectuals’ fury, who between the Seventeenth and Eighteenth centuries gladly insisted on the vague idea of a republican homeland so beautiful and lost. In a vast painting for the first time exhibited to the public since the 18th century, the painting, replicating nobly customary Pathosformel, played on the defeated people honoring the majesty of the victor, the representatives of the island of Majorca pay homage to the victor, a woman on a Throne who, with bold addition of imagery turns out to be, with the Tower in the background, Pisa.

The Tower thus as pars pro toto, but also as the insignia of the city. At the end of the 18th century, within probably that Arcadian circle in Pisa known for the militancy of authentic intellectuals such as Carlo Goldoni, but also of a cultural demi-monde easy to literary play, a sense for intellectual birignao developed that in Pisa led to a very fascinating result. That Trojan War painted at the end of the 18th century by Francesco Pascucci, globetrotting painter and protagonist of a minor classicism not devoid of cultured references, where the city besieged by the Greeks was sealed by high vertical walls, which had nothing, however, of those scee though medieval, not high enough not to hide, with studied negligence, the soaring presence of the Leaning Tower. A Pisa therefore transformed into the Homeric city.

Likewise, the Tower became the acronym and insignia of the city’s religious tradition. In Giovanni Battista Tempesti’s canvas, Saint Ranieri, the city’s patron saint, prays with troubled intensity and as if absorbed in a commotion not devoid of polished 18th-century elegance, leaving room for the opening to the right of the Tower and the Duomo. In an earlier painting, probably by Domenico Piastrini of Pistoia, angels accompany the patron in imploring the Virgin for her protection over the city, identified, indeed led, on a sort of tray furnished with miniature reproductions of the buildings in Piazza del Duomo.

In the body of this identification of the Tower in its dual civil and religious valence, the exhibition then seeks to account for how from the 18th century onward the building underwent a profound representational transformation, which corresponded to a change in perception, when the Tower began to elide itself from the rest of the square, as if it were a building that was sufficient unto itself. It was basically, and this does not seem a paradox, a form of monumentalization of the Campanile, which seemed to lose all religious and civil functions, to become a simulacrum of a bold and rare beauty, enriched by the stunning and complicated charm of its slope, which made it the monument of itself. This transition is especially appreciable thanks to the spread of prints, generally in etching, modulated to the alternating vicissitudes of specimens of resounding quality (such as those by Fambrini and Nascio), and others instead of more run-of-the-mill taste and low cost. With the highly cultured detail of a print by an unknown author but greatly replicated, where the Tower even lost its cylindrical appearance and the columnar planes were transformed into full walls, to bring the Tower closer not to a bell tower, but to the famous Settizonio in Rome: a monument therefore among monuments.

This process we said began to develop in the 18th century, and it was no accident, because the desacralization of the building was determined by the need to respond to the increasingly intense demand of a fascinated public eager to turn the Tower into the imprint of a presence, a souvenir. The era of the Grand Tour.

The needs of milords and tourists with baedeker in hand marked a profound transformation of the perception of the architecture we speak of: from Bell Tower, a place of bells, therefore liturgical, marking the spiritual time of a city, to Tower. From Bell Tower, to Leaning Tower. Just as in Franco Lucentini’s novel, News from the Excavations, when “the professor” finally in front of the remains of Hadrian’s villa, instead of understanding its meaning is lost in a time devoid of support and meaning, swept away by the confusing wave of ages and life. Only here the meaninglessness very often takes on the appearance of an indistinct, background buzz.

Hence the decision to open the exhibition with a section that emphasizes the primary function of the Tower, restoring its identity as a place that marks the time of faith and the faithful, curated by Francesca Barsotti.

It is then no coincidence that the Tower has over time become the fetish, or emblem, of some artists accustomed to playing with popular and sometimes even frayed images from constant visual consumption. The exhibition documents some examples of this, such as the Tower supported by Magritte’s spoon (or feather), or Haring’s radiant little man, to say nothing of the real passion endured by Futurist painters for the Tower. Just as ample space has been given to that very intense phenomenon even before the selfie era, that of photographs, documented here by beautiful black-and-white exhibits in a section curated by Manuel Rossi.

However, the exhibition, although not centered on the recent restorations (which would need an event of its own), could not fail to mention the attempts made since the 19th century to halt the rise of the Tower’s inclination, up to the recent interventions that have made it safe. Without being able to resist the temptation to devote at least a fragment of the exhibition to that marvelous and maddening series of restoration proposals that from the 1970s onwards arrived from all parts of the world on the tables of the Opera della Primaziale, which if they document how wacky man’s imagination can be, and shrewd the presumption, at least in one case was even fulminating, because that uncertain and slight drawing of a little Bengali girl suggesting that the Tower be saved without touching it, but rather by subtracting earth from under the foundations, so as to rebalance its set-up, was, though in an obviously more articulate way, the heart, it must be said, of the solution later adopted and successful.

And if the exhibition moves from the very first rooms with a section devoted to how living artists still measure themselves with the theme of the Campanile (Bartolini, Barbieri, Lucchesi), it is because it has not yet ceased to tell us something unprecedented. Which is, as we know, the deepest statute of the classics.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.