Imagine entering acontemporary art gallery. White walls house works by artists from all corners of the world: paintings evoking postcolonial struggles, installations telling stories of gender and sexuality, sculptures celebrating indigenous traditions. At first glance, we seem to be facing a revolution: at last, the art system seems to embrace the plurality of voices that has been excluded for too long. However, behind this apparent openness lies an uncomfortable question: how real is this change? How much, instead, is it the result of a system that has learned to dress itself in diversity without really transforming itself? And how much is it, instead, a strategy to respond to social pressures without really changing power dynamics?

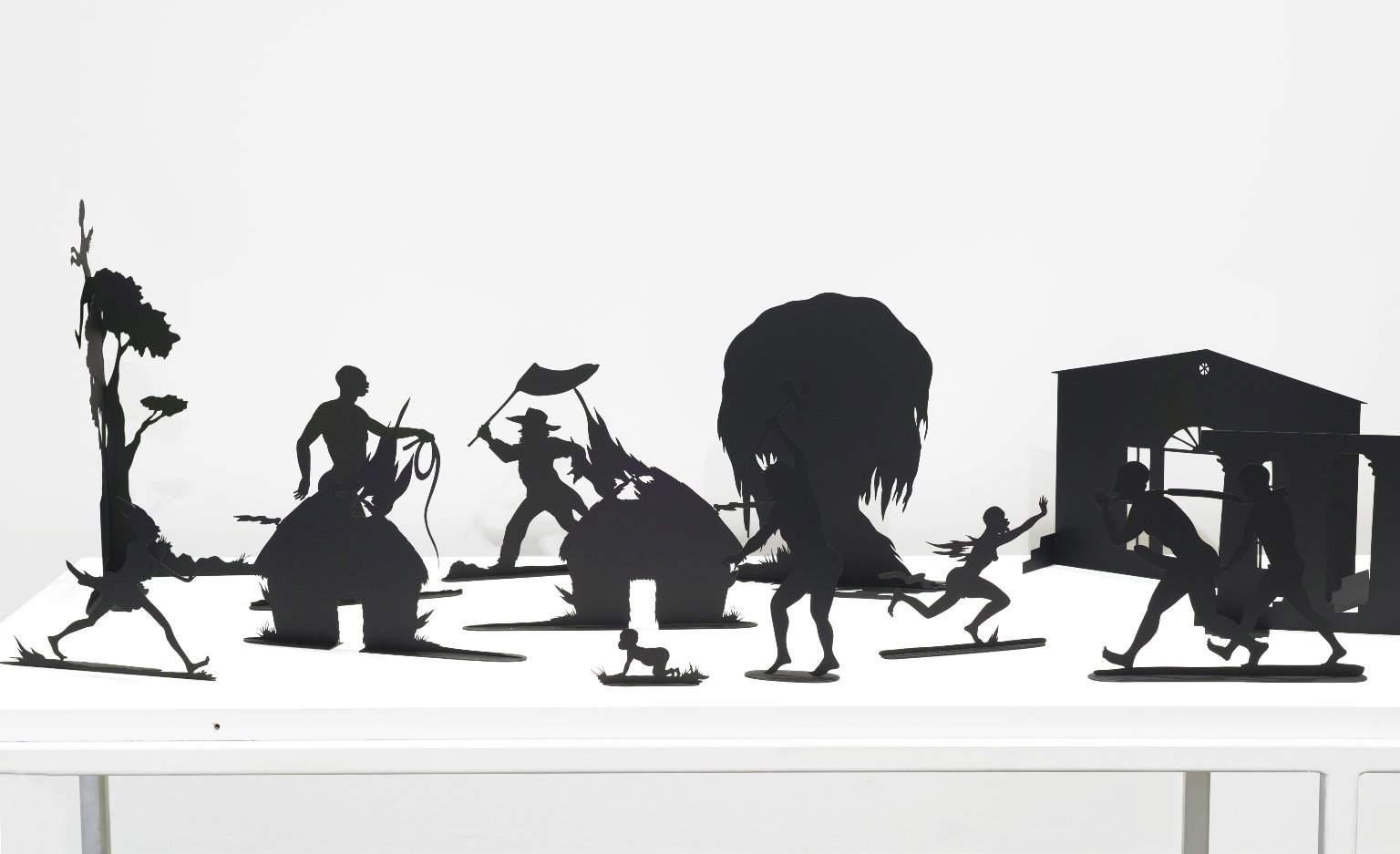

Looking at the contemporary art scene, it cannot be denied that there have been advances in terms of representation. Artists such as Kara Walker, Zanele Muholi or Tania Bruguera have won spaces in the most prestigious museums, and entire sections of fairs and biennials are devoted to promoting emerging voices from marginalized backgrounds. However, there is a fundamental difference between representation and transformation. Exhibiting diversity is not necessarily the same as changing the power dynamics that govern the art system.

Let’s look at who decides. Who are the curators, museum directors, collectors, and gallery owners who determine what is worthy of being exhibited, purchased, and celebrated? In many cases, these figures remain anchored in awhite, male, affluent elite. This means that even when a work of art tells stories of marginality or resistance, it is mediated and inserted into a system that continues to reflect values and priorities that have little to do with the plurality it is meant to represent. Diversity thus risks becoming a convenient tool to legitimize a system that has not actually changed in its structure.

The question of diversity in the art system is not only about who is represented, but also how and why. The contemporary art system is deeply rooted in Eurocentric and capitalist logics that define the value of art by its marketability and ability to attract attention in global markets.

The critical aspect is found in the way diversity is “consumed” by the contemporary art system. Artists from non-Western or marginalized backgrounds are often faced with a specific demand: to be representatives of an exotic or politically correct “other” that meets the expectations of global audiences. In this process, their works are packaged to be easily absorbed by the market, losing some of their complexity and critical potential. The result is a form of "domesticated diversity ," in which marginalized voices are present, but only in ways and contexts that do not challenge existing cultural and social hierarchies.

For example, an artist who explores the consequences of colonialism may be celebrated in major international exhibitions, but how much of that celebration translates into a real rethinking of the colonial structures that still permeate the art system? Individual histories and experiences become commodities, a product that can be sold and consumed without altering the mechanism that generates it.

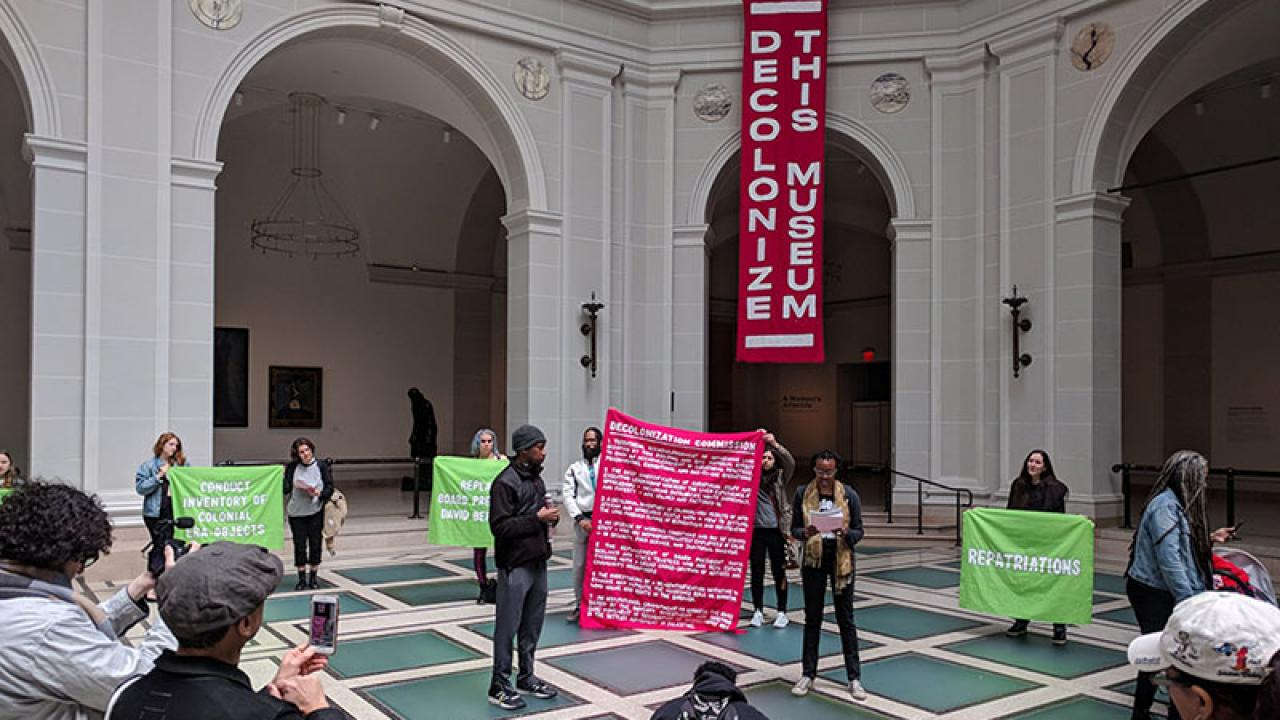

If true diversity is not limited to representation, but requires a transformation of power structures, then it is necessary to rethink the art system in its entirety. It is not just a matter of exhibiting artists of diverse origins, but of redefining who makes decisions and by what criteria. Decentralizing the system, promoting local institutions and independent art collectives, supporting alternative models of production and distribution-these are key steps to building a truly inclusive art ecosystem.

In this sense, initiatives such as Black Artists and Modernism in the United Kingdom offer an interesting model. They do not simply promote black artists, but critically analyze the way their works have been archived and interpreted over time, highlighting the dynamics of exclusion and marginalization. Movements such as Decolonize This Place or the Museum of Care are creating spaces for dialogue that transcend the logic of the market, putting community and social change at the center. These examples show that it is possible to imagine a different system, even if the road ahead is long and complex.

In the end, the fundamental question remains: are we willing to face the contradictions of the art system or do we prefer to settle for surface diversity? Art has extraordinary potential: it can not only reflect the world but also help change it. However, to realize this potential, it is necessary to go beyond appearances, question power structures and build a system that truly welcomes a plurality of perspectives.

The art world is not an island. Its contradictions reflect those of society as a whole. And perhaps therein lies its strength: in reminding us that every struggle for diversity and inclusion is, at bottom, a struggle for a more just and equitable society. But for art to drive this change, we must allow it to be what it has always been: a space for freedom, experimentation and transformation.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.