Castilla y León, a region in northwestern Spain, holds some of the nation’s most important cultural and natural treasures, witnesses to art and human life over the centuries. The region’s sites recognized as World Heritage byUNESCO represent exceptional universal value, deserving protection and enhancement in accordance with the terms of the 1972 World, Cultural and Natural Heritage Convention, ratified in Spain and incorporated into its legal system in 1982.

The region is home to a collection of cultural assets that tell the story of the complexity of European societies and their artistic and social evolution. Prominent among them are the Gothic Cathedral of Burgos, a symbol of medieval architectural genius, and the fortified cities of Ávila and Segovia, which preserve remarkably intact walls, palaces, and monuments. Salamanca stands out for its University and Plateresque architecture, while the Way of St. James bears witness to centuries of pilgrimages and cultural exchange. The ancient Roman mines of Las Médulas and the prehistoric sites of Atapuerca and Siega Verde complete the picture, offering valuable evidence of the lives and artistic practices of past peoples. Together, the sites present a singular overview of the historical and cultural richness of Castilla y León, confirming its central role in the history of Spain and its relevance to world heritage.

Burgos Cathedral represents one of the most remarkable examples of Gothic architecture in Spain, playing a central role in the dissemination of 13th-century artistic forms and profoundly influencing art and architecture between the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Located in the medieval city, at the foot of the castle and along the Pilgrim’s Way to Santiago, the cathedral reflects the historical and cultural importance of Burgos. The city itself, founded in 884 by Count Diego Rodríguez as a military enclave, began to develop in 1071, transforming between the 12th and 16th centuries into a thriving commercial center, reaching its peak in the Renaissance. During this period, the cathedral and the main parishes became essential landmarks along the trade routes and for pilgrims on the Camino de Santiago.

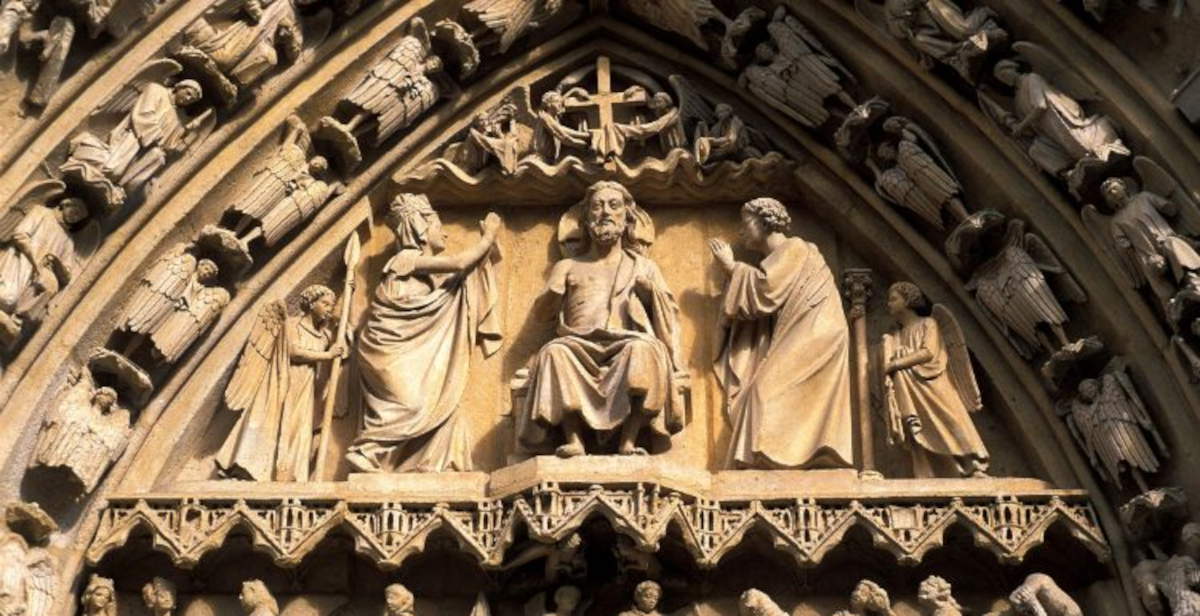

The present cathedral, built beginning in 1221 at the behest of Ferdinand III and Bishop Maurice, replaced an earlier 11th-century Romanesque cathedral. Between the 15th and 16th centuries, the Colonia family enlarged the main chapel and built the Constable’s Chapel, the tower spires and the dome, rebuilt by Juan de Vallejo, while Diego de Siloé designed the Golden Staircase. The plan of the building includes three wide naves, around which are thirteen irregularly distributed chapels, and a central nave in the shape of a Latin cross, with a transept of the same height as the main nave. Notable features include the Gothic doors of the Sarmental and Coronería and the Renaissance door of the Pellejería.

Burgos Cathedral contains, in its chapels, stained glass windows, tombs, altarpieces and furnishings, the main artistic innovations of the late Middle Ages and early Renaissance, complemented by extraordinary Baroque examples. The Gothic architecture, enriched by major extensions and modifications in the 16th century, is an outstanding example of harmony and artistic creativity, a lasting testimony to the genius of the masters who worked there.

Segovia is distinguished primarily by its Roman aqueduct (read our in-depth study here), one of the city’s most emblematic monuments, but it is also an outstanding example of the coexistence of Christian, Muslim, and Jewish cultures, evidenced by its extensive monumental heritage distributed in distinct districts. The city is located in the southeast of the region, on a rocky rise over 1,000 meters above sea level, and overlooks the Eresma and Clamores rivers, surrounded by orchards and forests that accentuate its picturesque charm. With Celtiberian roots, Segovia assumed great prominence during the Roman Empire, minting coinage and later becoming a Visigothic settlement. It retains a valuable Romanesque complex, and in the late Middle Ages its textile industry rose to prominence, culminating in the 16th century.

The Roman aqueduct, built around A.D. 50, stretches for nearly 15 kilometers and has more than 20,000 stone blocks assembled without mortar, in perfect balance. Today it is in an extraordinary state of preservation. Other notable monuments include the 11th-centuryAlcázar and the 16th-century Gothic cathedral, considered together with the New Cathedral of Salamanca to be one of the last examples of Gothic architecture in Spain. Also notable are the Romanesque churches of San Juan de los Caballeros, San Lorenzo, and La Veracruz, along with numerous civic structures, arches, portals, and courtyards. Segovia also plays a historical role: at the Alcázar, Isabella the Catholic was proclaimed queen of Castile in 1474, and the city later became one of the main centers of the War of the Communities.

The city of Ávila is an excellent example of a medieval fortified city, famous for having preserved its walls in their entirety and for its rich heritage of civil and religious monuments. Located in the south of the region, Ávila stands on high ground overlooking the right bank of the Adaja River. The first settlements date back to the Vettones, a Celtic people who inhabited the peninsula before the Romans, in the 7th century B.C., but it was the Romans who defined the urban structure of the city. Later, with the arrival of Arab culture, Ávila was reconquered in 1085, when work began on the construction of the city walls. Its heyday coincided with the era of the Catholic Monarchs, despite the demographic decline caused by the expulsion of Jews and Moors. In the 16th century the city gained further fame as the birthplace of St. Teresa of Jesus.

The walls, an undisputed symbol of Ávila, are among the best preserved in all of Spain. Within the walled perimeter are fine religious buildings, including the cathedral, considered the first in the Spanish Gothic style, as well as palaces and stately homes that reflect the mystical and military character of the city. Outside the walls, the four Romanesque churches included in the heritage declaration deserve attention: San Vicente, San Segundo, San Andrés, and San Pedro.

The ancient city of Salamanca is distinguished by the presence of a high number of monuments of historical and artistic significance, ranging from Romanesque and Gothic to Arab, Renaissance and Baroque styles. In truth, what most identifies Salamanca is the plateresquestyle and thecity’s historic University . Located in the southwest of the Autonomous Community of Castilla y León, the city stands on three hills along the right bank of the Tormes River. Its territory preserves traces ranging from the Paleolithic to the Celts and Romans. Conquered by the Arabs, Salamanca was rebuilt and repopulated in the early 12th century. Its development gained momentum in the 13th century with the founding of the University, while in the 16th century it achieved further prominence thanks to the great humanists. In the 18th century it became a center for the art of the Churriguera, whose influence extended as far as Latin America.

One of the city’s most distinctive features is the golden color of Villamayor stone, used for most of its historic buildings. Notable monuments include the University, begun in the early 15th century; the Old Cathedral, work on which began in 1140; the New Cathedral (16th-18th centuries); and the Plaza Mayor, designed by Churriguera and begun in 1729. Salamanca constitutes a monumental complex of exceptional value, which has remained substantially intact and is capable of demonstrating the city’s historical and cultural continuity to the present day.

The Camino de Santiago represents one of the most relevant pilgrimage routes in Europe, with a role that goes beyond the spiritual dimension: since the Middle Ages it has been a route of communication and cultural exchange, maintaining its importance to the present day. In Spain, the Camino is divided into several access routes to Santiago: the Camino del Norte, the Vía de la Plata, the Camino Inglés, and others. Among these, the French Way stands out for its wide historical spread and the monumental and cultural impact it has left behind. It starts in Valcarlos, Navarre, and the route passes through the Autonomous Communities of Aragon (Huesca and Zaragoza), La Rioja, Castile and Leon (Burgos, Palencia, and León), and Galicia (Lugo and A Coruña). The route touches renowned towns and villages, including Jaca, Estella, Logroño, Santo Domingo de La Calzada, Nájera, Burgos, Castrojeriz, Frómista, Carrión de los Condes, Sahagún, León, Astorga, Ponferrada, and Villafranca del Bierzo, until it reaches Santiago de Compostela.

Before the remains of the apostle James the Greater were kept in the city, pilgrimages moved for cultural and social reasons, with the goal of reaching the Spanish town of Finisterre. The first religious pilgrimages started from Oviedo in the 9th century along the so-called Primitive Way. In fact, the expansion of pilgrimages was consolidated in the 11th century thanks to the support of Kings Sancho III the Great, Sancho Ramírez of Navarre and Aragon and Alfonso VI, who promoted the construction of churches, bridges and hospices along the route, giving rise to the French Way. During the Middle Ages, the Christian route thus took on extraordinary importance, leaving a major artistic and cultural legacy and fostering the passage and influence of people, ideas and traditions throughout Europe.

The gold mines of Las Médulas represent one of the most outstanding examples ofRoman ingenuity in open pitmining. Located to the west of León (not far from the border with Galicia), the area is characterized by a terrain composed of pebbles, sand and clay, where gold does not occur in lodes or compact masses. In order to extract the metal, the Romans had to work huge amounts of material, shaping a landscape recognizable today by the steep clay walls, tunnels and caves they dug, surrounded by chestnut forests. Mining reached its peak during the reign of Trajan, between the end of the first century and the beginning of the second century AD. The decline began around 150 AD, while the final abandonment of the site did not occur until the early 3rd century.

Las Médulas thus retains incredible value for its extent, the number of archaeological traces, but also for the state of preservation of the structures. The mines constitute a landmark in the study of mining history, revealing the impressive Roman technology and the enormous transformation of the territory and local communities. They demonstrate the organization, economy and society of the time, presenting a singular view of the relationship between man, natural resources and the environment.

The archaeological site of Atapuerca consists of a complex of places where the oldest and most numerous remains of human beings have been found. It is located in the Sierra de Atapuerca, a hillside near the city of Burgos, stretching from northwest to southeast along the Arlanzón River valley. The archaeo-paleontological record of Atapuerca covers a time span from about a million years ago to about 100,000 years ago. Notable among the main sites that make up the complex are the Gran Dolina, the tunnel-covacha de los Zarpazos, the Penal site, the Sima del Elefante, the Sima de los Huesos, and the Mirador.

The fossil remains of the Sierra de Atapuerca present an incredible reservoir of information on the morphology and lifestyle of early European human communities. Among them emergeHomo antecessor, (perhaps a direct ancestor ofHomo sapiens), dated to over 780.000 years ago and unique in the world for its evidence, andHomo heidelbergensis, progenitor of the European Neanderthals, whose remains, due to their abundance (amounting to 80 percent of those known worldwide), variety and quality, represent a fundamental reference for studies on the evolution of the genusHomo. The faunal remains and archaeological tools found at Atapuerca are also of exceptional value, both for their antiquity and quantity, providing direct evidence of the daily life of early human communities.

The Siega Verde complex represents an extension of the Portuguese sites of the Côa Valley, which were added to the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1998. Together, the sites constitute the most importantset of open-air Paleolithic rock art on the Iberian Peninsula. The complex is located at the western end of Salamanca province, near the border with Portugal. The rock carvings are visible on shale outcrops along the bridge over the Águeda River, known as Puente de Siega Verde, and extend over an area of about one hectare, mainly following the left bank of the watercourse.

The rock ensemble includes 91 panels on which about 450 figures have been identified. These include equids, aurochs, bison, deer, reindeer, megaceros and roe deer, typical of the fauna of that period, along with anthropomorphic representations and abstract symbols of great figurative value. All the figures were made by means of tapping or engraving techniques on the rock. The stylistic, technical and thematic aspects place these works in the Upper Paleolithic (20,000 to 11,000 B.C.), the era of development of the Solutrean and Magdalenian cultures. Siega Verde and the Côa Valley present an outstanding example of early human symbolic creation gestures, while revealing the forms of life, economy and spirituality in the early stages of human cultural development.

|

| Castilla y León: a trip to Spain's UNESCO sites |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.