In one of the last articles in our travel section, we had told you about the Malatesta Library, dwelling, however, only on ... the 15th century. There was in fact so much to be said about Malatesta Novello’s Renaissance dream, the Nuti Hall, the symbols it contained, what the Library represented when it was built, and what it still represents today. So today we conclude this itinerary, which takes us back to Cesena, to discover another library, a visit to which is included in the Malatestiana Library itinerary: the Piana Library, preserved in the large hall that opens right in front of the Malatestiana.

The Piana owes its name to the fact that its owner was a pope, Pius VII, so much so that, especially in specialized texts, it is not difficult to find the spelling Pïana, with the diaeresis on the “i,” precisely to better emphasize the origin of the term. Pius VII, born Barnabas Chiaramonti (1742 - 1823), was one of the three popes from Cesena, thanks to whom Cesena also earned the nickname of the city of three popes: two who were born in Cesena (Pius VI and Pius VII) and one who was bishop of the city (Benedict XIII). In fact, Pius VIII was also bishop of Cesena: but, you know, nicknames often contemplate some minor forcing! Let us return, however, to talk about the Library: for several years, after the pontiff’s death, the collection remained the property of the Chiaramonti family even though, already at the time when Pius VII was alive (and since 1821 to be exact), its use had been granted to the Benedictine monks of Cesena, who resided in the abbey of Santa Maria del Monte. Following ups and downs, in 1941 the entire collection came to the state, which granted it on deposit to the Malatestiana.

|

| The hall that houses the Biblioteca Piana in Cesena |

Pius VII, just like Malatesta Novello almost four centuries earlier, was moved by a strong passion for letters, the arts, archaeology and culture in the broadest sense, as well as a very modern mentality: let us not forget that, just two years after his inauguration on the throne of Peter (we are in 1802), he compiled the so-called chirograph (literally, “handwritten text”), a document that established various norms for the protection of cultural property, and conferred on Antonio Canova the appointment of Inspector General of the Antiquities and Fine Arts of the State , a sort of ancient version of today’s superintendent. It was also thanks to Pius VII’s measures that several works stolen during the Napoleonic spoliations were able to be returned.

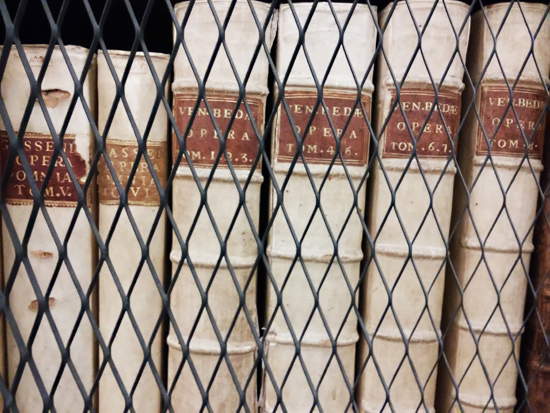

Pius VII’s interest in archaeology, the sciences, and the modern discipline of museology, which was beginning to take shape in those very years, is reflected in his choices for his own book collection. A collection that was also the result of a modern mentality: the pope, for example, returned to their rightful owners the volumes that had been removed, under Napoleonic rule, from the convent libraries and had been gathered in the Vatican Library. And, something that may seem strange to an art lover, Pius VII cared more about content than form: in other words, he did not like to collect rich illuminated manuscripts, but accorded his preferences to the printed volumes that he found most useful for his studies. The exact opposite of the other pope from Cesena, Pius VI, who was a passionate bibliophile always on the lookout for the finest rarities, and who set up a collection that is now dispersed. It will come as no surprise, then, to learn that the Biblioteca Piana today holds almost three thousand works (a total of about five thousand printed volumes) and just a hundred or so manuscripts, most of which, moreover, came from the donation, dating back to 1814, of a Roman nobleman, Marquis Giovanni Giacomo Lepri. Thus, among the printed works we have religious texts as well as Italian and Latin classics, but also texts on numismatics, art, archaeology, science, and even works on local history (such as a 17th-century Caesenae Chronologia, “Chronology of Cesena,” which reports salient facts of the city’s history). There was no shortage of important editions in the collection, such as an Aeneid illustrated by, among others, Vincenzo Camuccini and Antonio Canova, published in 1819, and Joan Blaeu’s impressive Grand Atlas, a twelve-volume geographical atlas published in 1667.

|

| Printed edition of the works of Bede the Venerable, preserved at the Biblioteca Piana |

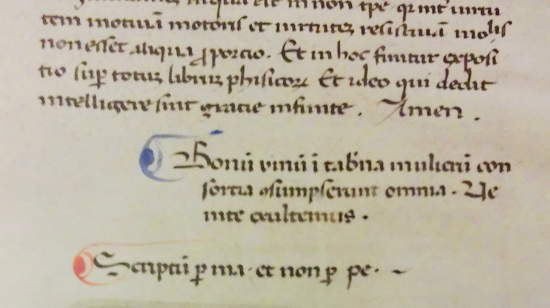

Among the manuscripts, we find such valuable codices as an Evangeliary (i.e., a book collecting the four gospels) from 1104, the 15th-century Roman Missal, the Sentences of Peter Lombard dating back to the 13th century, and a manuscript with the Rules of the Augustinian nuns dated 1390. Also present are a number of incunabula, the term used to indicate the first printed books in history, from the date of the invention of printing (1453, the year from which the first incunabulum was published, a Bible printed by Gutenberg in Mainz) until, approximately, 1500: among them is a Cosmographia by Ptolemy, probably printed in 1477, and illustrated with plates on drawings attributed to Taddeo Crivelli. The visitor will also find, in the space where the Biblioteca Piana is now housed, some codices from the Malatestiana that are shown to the public: in fact, the codices preserved in the plutei cannot be observed up close. Thus, codices of which we have also been handed down the name of the amanuensis, who not infrequently affixed his signature in theexplicit, the final notes of the manuscript, are on display: we can thus make the acquaintance of copyists such as Jean d’Epinal, John of Mainz, Andrea Catrinello, and a very likeable German, Mathias Kuler, who ends his codex (for the record, it is a work by Walter Burley, the Commentary on Aristotle’s Physics) by writing “Bonum vinum in taberna, consortia mulierum consumpserunt omnia” (which, translated, sounds something like this: “everything I have earned from this work I have squandered on wine and women”: a kind of 15th-century George Best... !).

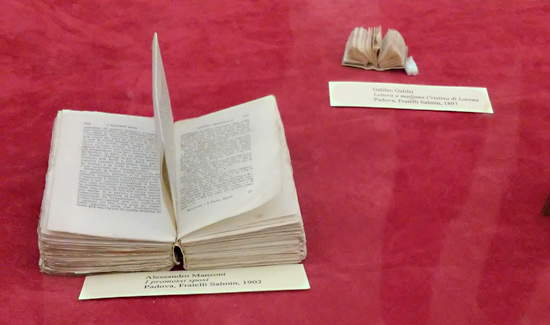

It is also necessary to mention Cardinal Bessarione’s chorale cycle: the chorale was an important book, also manuscript, that contained scores and texts of the songs with which to accompany liturgical services in church. Those we find in Cesena were commissioned, as anticipated, by Bessarion, the powerful Greek cardinal who at the Council of Ferrara in 1438 was among the most ardent supporters of reconciliation between the Roman and Orthodox churches. Bessarion, between 1450 and 1455, was papal legate for Bologna and for Romagna, and it was during these years that he commissioned the cycle of chorals that is now known by his name: these are eighteen volumes originally intended for the convent of the Observant Franciscans in Constantinople, which later remained in Cesena and were included in the collection of the Municipal Library following the suppression of religious orders under Napoleonic rule. Today they occupy a prominent place in the room that houses the Biblioteca Piana, just as great importance is given to some curious editions that enriched the Library’s holdings in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. This is the case of a rare pocket edition of The Betrothed, published in Padua in 1902 by Fratelli Salmin, and especially of a reproduction of a Letter of Galileo Galilei to Christina of Sweden, also published by Fratelli Salmin, in 1897: the peculiarity of the latter volume consists in the fact that it is the smallest book in the world that can be read without a lens. A rarity, printed for theTurin General Exhibition in 1898, measuring just fifteen millimeters by nine!

Peculiarities preserved in a place that belongs to the artistic and cultural heritage of a city that is certainly not a regular tourist destination, but definitely worth a visit to admire its beauty and to understand the extraordinary care with which its citizens protect it.

|

| One of Cardinal Bessarione’s Chorales. |

|

| The Pocket Edition of the Promessi Sposi and the tiny Lettera di Galileo, the smallest book in the world that can be read without a lens |

|

| Explicit from the codex copied by Mathias Kuler (who at the bottom adds: Scripsi p. ma. et non p. pe, or “I wrote it with my hands, not my feet”) |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.