There is another Naples, besides the one that can be seen under the blue sky of Campania: it is the underground Naples, a sort of city within a city that develops underground in the Campania capital. A thousand-year stratification with tunnels, galleries, catacombs, crypts, air-raid shelters, remains of aqueducts, underground environments and much more. Much of what is found today in the underground of Naples can be visited from different access points and with different routes, to learn about the history of the city from another point of view, a point of view that is decidedly ... deeper than those usually known. Not to mention that even in the bowels of the city are hidden works of art and incredible works of human beings that stand out for the originality of the solutions used to exploit the underground environments, but also for the scenographic way in which they present us.

It is a real world to explore, obviously not suitable for the claustrophobic in some cases (it is necessary to ask for information in advance: there are very large places, but also some narrow and oppressive tunnels), which can be visited all year round (beware, many rooms are cold even in the middle of summer), in different ways and with different routes, from the classic walking and short duration ones to tours on rafts in the cisterns, or candlelight tours. Not everything can be visited: to have a better experience, one should avoid DIY and rely on authorized routes, also for safety reasons.

This is a large underground tunnel, a tunnel with very high walls dug under the hill of Pizzofalcone, near the Royal Palace. The underground viaduct was designed in the second half of the nineteenth century by Errico Alvino at the behest of King Ferdinand II of Bourbon, who intended to have a military route built that would be easy and quick to navigate in order to defend the palace, i.e., the center of power of the kingdom: the route was therefore to be traversed quickly by the military in case of need, as well as by the inhabitants of the palace themselves should it become necessary to escape. It was a large, trapezoidal-shaped tunnel with two “carriageways,” two tunnels for the opposite directions of travel, separated by a parapet where the lampposts necessary for lighting were installed. A futuristic project that took only two years to complete (in fact, the king was able to inaugurate it as early as 1855). The path, however, never served the purpose for which it was designed: it would be reused only during World War II as an air raid shelter, and later, after the war, it became a municipal depot. Part of it instead was used as a parking lot. Between 2005 and 2007 it was secured and enhanced as a cultural site, which can now be visited independently or with one of the Naples Underground routes.

Also known as “Virgil’s Cave,” it is a 705-meter-long tunnel, carved into the tuff, that extends under the Posillipo hill, between Mergellina and Fuorigrotta. It is a very ancient environment: it is from the Augustan age and was built by Lucius Cocceius Aucto, Agrippa’s architect. Already mentioned in the Tabula Peutingeriana, it was originally a military infrastructure connecting the city of Naples to the area of Pozzuoli: it owes its name “Virgil’s Cave” to the legend that Virgil built it in a single night with the use of magic (in fact, near the Crypta there is a cenotaph traditionally known as “Virgil’s tomb”). Given its importance as a military communication route, the Crypta remained in use until the late 19th century, when it was decreed to be closed for static reasons. Today the Crypta can be visited, and is one of the Ministry’s cultural sites.

This is a complex of underground cemeteries from the 4th-3rd centuries BC located about ten meters deep: most of the tombs are located underground in the Sanità district. The most famous of the Hellenistic hypogea is the Hypogeum of the Cristallini, dug into the tufa beneath what is now Via dei Cristallini. This complex was discovered in 1889 and was published a few years later: it consists of four hypogea with burial chambers, each with independent entrances. On the street level, however, there was a vestibule that was used to perform funeral rites, and from here then there was access to the tombs: one of these still has its wall decorations. The head of Medusa carved in tufa decorating the wall of Tomb C is famous. Some inscriptions in ancient Greek have handed down to us some names, probably those of the people who were buried here.

The “buried Neapolis,” as it is called by the Opera di San Lorenzo Maggiore, is the most important archaeological site in the historic center of Naples: here, in fact, one can see the remains of the Neapolis forum, which in turn coincided with the former agora, or the center of civil and religious life in the Greek and Roman city. The archaeological area (a “non-claustrophobic route,” the museum is keen to point out: the spaces are indeed very large) is developed ten meters below the church of San Lorenzo Maggiore: in addition to the forum, one can see the macellum, the ancient Roman market of the 1st century BC.C. where the food vendors’ stores were located; the cardo, i.e., the main street of the ancient city; the tabernae, i.e., the stores where commercial and craft activities took place; and the cryptoporticus (covered market). The whole is surprising in its state of preservation and legibility of these important remains. A visit to the archaeological excavations is included in the ticket to visit the Museo dell’Opera di San Lorenzo.

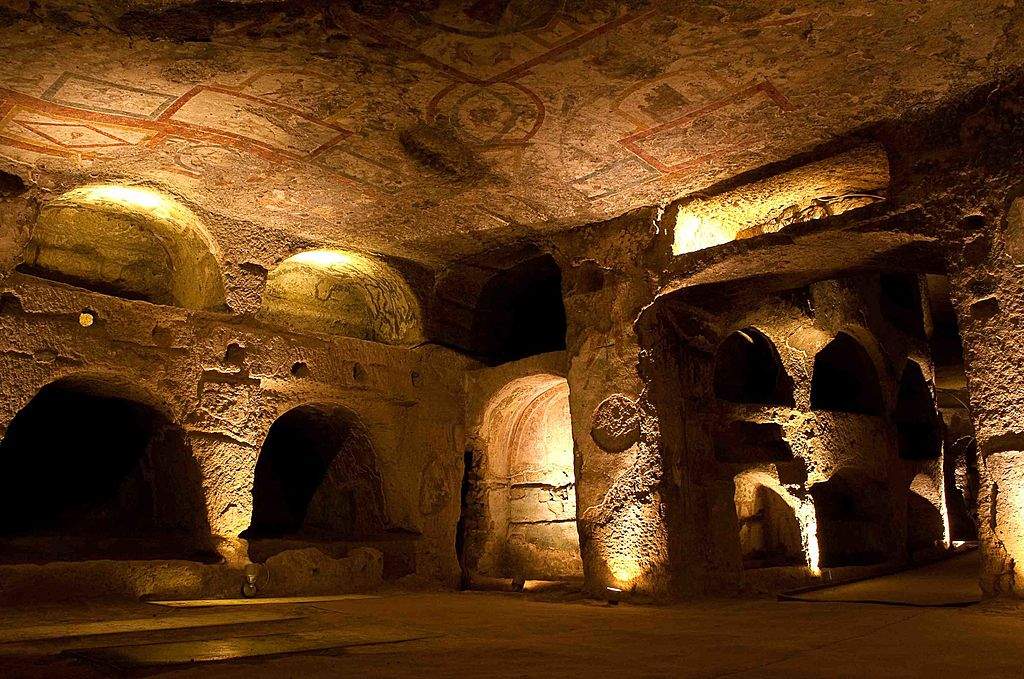

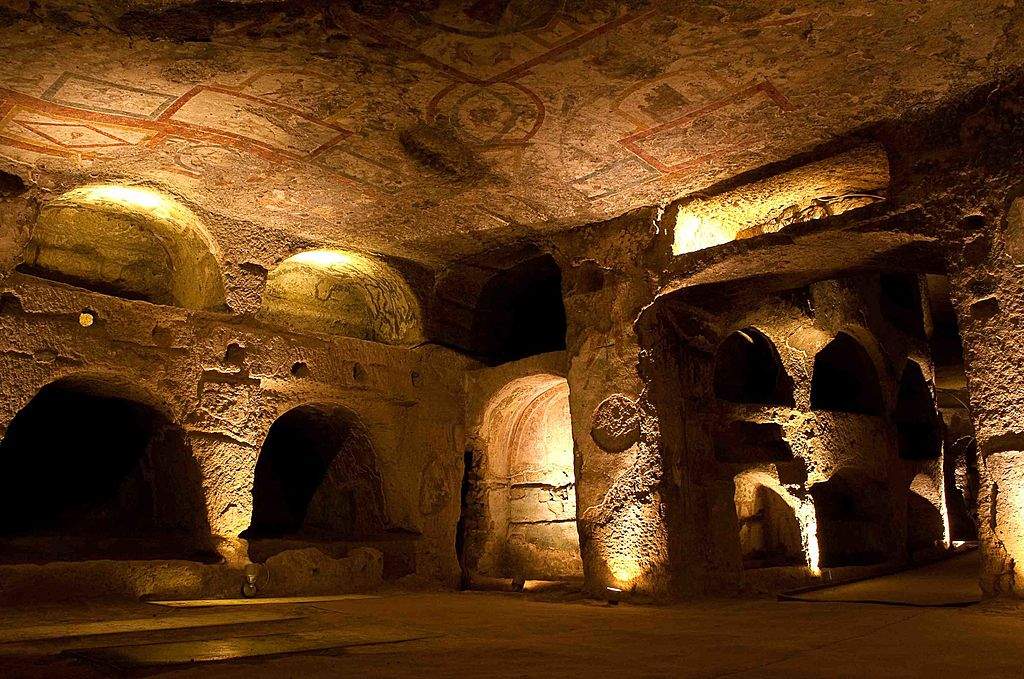

Catacombs are the ancient underground cemeteries of the Roman era: in Naples there are several and spread throughout the city, although most catacombs are located in the Sanità district. The most famous are certainly the catacombs of San Gennaro, dating back to the 2nd century, and whose entrance is currently located near the church of the Immacolata in Capodimonte: moreover, the oldest known portrait of St. Gennaro is preserved in these catacombs, and several remains of many wall paintings can be seen here, with figures of saints. Particularly spectacular are the two large vestibules, the lower and the upper (the latter characterized by a large frescoed vault in Pompeian style from the 2nd-3rd centuries), with large arched structures. Also particularly famous are the fourth- to fifth-century catacombs of San Gaudioso, known for its macabre frescoes with sunken skulls, and those of San Severo, which lie beneath the church of San Severo fuori le Mura.

The ancient aqueduct of Naples was built beginning in the 4th century BC, when Neapolis was a Greek colony. The structure was later expanded by the Romans, who built a dense network of underground tunnels and cisterns to make the water supply capillary in and around the city (the network reached as far as Pompeii, Herculaneum, Acerra, and Bacoli). This was such an important work that it continued to function for centuries, until the 19th century. Closed for good in 1884, the Greco-Roman aqueduct went into decay in the following decades, and became a sort of dumping ground. Turned into an air raid shelter during World War II, it has now been recovered and can be visited with access from San Gaetano Square 68. In addition, a “Museum of the Underground of Naples” has also been created on the premises of the ancient cisterns, which tells the story of the underground world of the Neapolitan city through artifacts found in the excavations (such as ancient oil lamps, tools and instruments used by quarrymen, and systems for drawing water) and historical evidence.

Another monumental tunnel, a kind of tunnel about 800 meters long that runs under the Posillipo hill to connect the Bagnoli plain with the Gaiola area: it too was designed by Lucius Cocceius Aucto, and yet owes its name to Lucius Aelius Sejanus, prefect of Tiberius who had the route of the tunnel modified to connect Posillipo with the ports of Pozzuoli and Cumae. The frotta is part of the Pausylipon Archaeological Park and can be accessed from the entrance on Via Coroglio. The cave is actually a large tunnel with impressive arches that ends right at the Archaeological Park set up on the site of the villa of Pausylipon, which belonged to the Roman patrician Vedio Pollione, a friend of Augustus (“Pausylipon,” from which the current toponym of “Posillipo” derives, means “place that makes afflictions cease”). The cave of Sejanus was discovered in 1841, and attracted for its grandeur and originality many visitors already at the time. Its current appearance is due precisely to the restoration work of the Bourbon era: originally the path was wider and with two directions on which wagons passed in both directions. Seiano Cave was also used as an air raid shelter during World War II. It has been passable again since 2009.

This is a cavity that is part of the dense network of tunnels that runs underground in Naples. It is located under the Quartieri Spagnoli and owes its name to the fact that the entrance is located at number 52 vico Sant’Anna di Palazzo. Discovered in 1979, the Sant’Anna di Palazzo air shelter was the first site in underground Naples to open to the public. It is about 40 meters deep and consists of a large room of about 3,200 square meters that during the war could accommodate about 4,000 people who were thus sheltered from the bombs. See the graffiti on the walls that genuinely and characteristically tell the thoughts and concerns of that historical moment.

This is the underground route of the Pietrasanta Basilica, converted into a “Water Museum” that opened to the public in the summer of 2021. The visit allows visitors to take a descent underground to see the cisterns of the Aqueduct of the Bull, which was part of the ancient Greco-Roman aqueduct, located right under the Basilica and operated until 1885: you can see the structures of the ancient aqueduct (such as the Cistern of the Eels and the Hall of the Waves: the latter is the largest ancient cistern in the historic center of Naples) as well as artifacts that tell the story of the water supply of Naples in the past.

The undergrounds of Castel dell’Ovo were first opened to the public on an experimental basis in the summer of 2019, for one month, with organized guided tours led by professionals. These are the dungeons of the ancient castle by the sea, between the neighborhoods of San Ferdinando and Chiaia: among the passages that can be visited are the Basilian catacombs, the church of San Salvatore, the hermitage of Santa Patrizia, the Hall of Columns, as well as the tunnels and secret passages of the ancient castle. In fact, Castel dell’Ovo looks more like a fortified citadel than a castle, and was expanded throughout the ages (its origins are in fact very ancient). The name comes from a legend, according to which Virgil allegedly hid an egg in the dungeons of the fortress that would hold its entire weight: if the egg broke, the whole castle would collapse into the sea. It is not always possible to visit them: it is therefore advisable to inquire in advance.

|

| Underground Naples: how to see it, what to see, which sites to visit |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.