In the heart of Salento, close to the Roman road that joined Lecce and Otranto, today the provincial road Squinzano - Casalabate, stands what can be considered one of the wonders of the medieval age of the entire Salento area: theabbey of Santa Maria di Cerrate (or “delle Cerrate”), a true cross-section of Greek-Byzantine art in Apulia.

Characteristic of the Salento imagination is that expanse of olive groves among which the typical masserias merge, becoming one with the landscape; the abbey in question also had a masseria function, as it became a center of agricultural production for olive processing, after having been one of the most relevant Byzantine monasteries in southern Italy. A place, therefore, where the main personalities of the Salento are intertwined: on the one hand, the strong religiosity of the South, and on the other, agricultural activity.

Its history, beginning with its foundation, also possesses a dual soul, legendary and historical. According to legend, the abbey was founded by the Norman king Tancredi d’Altavilla, count of Lecce, following a vision of the Virgin Mary that occurred after the king chased a fawn that had taken refuge in a cave during a hunting trip (hence also the toponym: “Cervate,” later to become “Cerrate”). Historical evidence, by contrast, dates the abbey to the beginning of the 12th century, precisely following the settlement of Greek monks, followers of the rule of St. Basil the Great, by Bohemond of Altavilla, son of Robert Guiscard, the first Norman to become duke of Apulia, Calabria and Sicily.

Precisely to the 12th century date the first known documents mentioning the abbey of Santa Maria di Cerrate: 1133 goes back to a document in which the Norman-born Count Accardo II of Lecce, lord of Lecce and Ostuni, in a deed of gift for the Benedictine monastery of St. John the Evangelist speaks of a land that extended “ab finibus terre communis ipsius Cisterni et sancte Marie de Cerrate cum suis pertinentiis” (i.e., "from the boundaries of the lands of the community of Cisterna and Santa Maria di Cerrate with its appurtenances). The abbey is then mentioned in a manuscript, a copy of Theophylact’s Commentarii on the Gospels finished “on April 3, 1154 by Simon, notary for Paul egumen of S. Maria di Cerrate, the year of the death of Roger our king” (Roger II of Sicily disappeared precisely in 1154). However, these are dates that do not allow us to know at what point the work was in progress, nor what bodies of the complex were already built at that time.

Of the Basilian monks we have testimony thanks to the intense activity that a library and a scriptorium (where the manuscript just mentioned was also produced) had at that time, places presumably related to them, since it is known that in the daily activities of the monks reading, studying and amanuensis copying were frequent. The Greek monks had come to Salento to escape the iconoclastic persecutions of Byzantium, perpetrated by those in the Byzantine Empire who rejected the worship and use of sacred images. Until the 16th century, the monastery of Cerrate continued to remain an important cultural religious hub in the Salento area; from 1531, the site was placed under the control of theOspedale degli Incurabili of Naples , which, following the deed of gift from Pope Clement VII, managed it for nearly two centuries. The complex was then transformed into a masseria that included the abbey church, stables, lodgings for the farmers, two underground oil mills (typical of the Salento, these are those dug into the rock, thus underground, which allowed better preservation of the olive oil produced by the surrounding centuries-old olive trees), a well and mill. We know from sources that in the seventeenth century there were at least two stables and three dwellings, which housed not only the farmers but also the monks and any guests who arrived from outside to buy the farm’s products.

|

| The abbey of Santa Maria di Cerrate. Ph. Credit FAI |

|

| The apse of the church. Ph. Credit FAI |

|

| The portico. Ph. Credit FAI |

In 1711, due to the sacking of Turkish pirates, the monastery-masseria was abandoned and fell into a ruinous degradation that continued until 1965, when the Province of Lecce took to heart the condition in which the entire complex was and favored its restoration, starting a series of interventions that were directed by architect Franco Minissi.

The abbey at the time was severely compromised due to the years of abandonment (when the interventions started, the conditions of preservation were very bad: the farmers who had used the abbey as a farm for a long time had not gone very subtle with the frescoes, decorations, floors). The situation was so critical that when the construction site was opened there was, in April 1967, the collapse of the bell tower that had been built in the early twentieth century to replace the old seventeenth-century bell gable tower, which had also collapsed in the late nineteenth century. However, overall the structure was sound: it was, however, badly deteriorated due to poor maintenance.

Interventions moved in two directions: on the one hand to preserve as much as possible what could be kept, and on the other to recover some spaces that would be used as a museum to house the works that could no longer be kept in their original locations (today the museum conceived in the 1960s is called the “Museum of Popular Arts and Traditions”). Minissi’s action, explains architect (and architectural historian) Beatrice Vivio, “aesthetically placed itself somewhere between the option of traditional reconstruction and that of perpetuating the lacuna, technically adequate to guarantee the preservation of the environments attacked by atmospheric agents by lightening the structure.”

The restorations first involved the church, which was given a new roof: “a tiled roof,” Vivio wrote, “lightened with corrugated metal sheet resting on a wooden framework, with an interposed layer of reeds reminiscent, at the intrados, of seventeenth-century technology.” A similar roof was made for theambulatory, then the barbican (an exterior wall with defensive functions) that had been leaning against the southwest corner of the church was demolished (an operation that, Vivio explains, “exposed a preexisting subfoundation under the apses, which was reintegrated in ’cuci-scuci’ along the entire south elevation”), then the single-lancet windows were reopened, work was done to put the sloping columns back to plumb, the parts most at risk were consolidated, and the lesions were repaired. Not everything was maintained: writes Vivio that the extraneousness of the logic of the original layout of certain bodies in a precarious state of preservation led to the “removal of a sacristy juxtaposed to the south side of the church” and the “demolition of the buttress leaning against the main facade, considered superfluous after the appropriate static checks.” The other parts of the building were then rearranged: the former oil mill was salvaged and used to house the museum that would hold the frescoes removed by the tearing technique in the 1970s, which were removed to uncover the more important and older frescoes underneath, which were still preserved.

|

| The thirteenth-century portal. Ph. Credit FAI |

|

| The underground oil mill. Ph. Credit Sergio Limongelli |

In 2012, the Province of Lecce, as the outcome of a public tender, entrusted the abbey of Santa Maria di Cerrate in a 30-year concession to FAI - Fondo Ambiente Italiano, which reopened the site to the public, although the restorations are not yet finished. Some were conducted recently, between 2015 and 2018, for the total sum of two and a half million euros: these are the restoration of the former monastic house (i.e., the former site of the scriptorium and the monastic library), which now houses the services for the public (the ticket office and information point, a small refreshment bar and a bookshop), the restoration of parts of the church and its thirteenth-century portico, and the restoration of the farmer’s house (formerly also used as a stable), which is intended as a multipurpose space, a venue for activities, conferences and events. Moreover, all the buildings have undergone seismic upgrades and roofing improvements during the restorations in recent years: for example, a rainwater harvesting system is being planned to safeguard the structures from humidity and reuse rainwater in an environmentally friendly way.

The exterior is presented in its imposing Romanesque appearance (the abbey of Santa Maria di Cerrate represents one of the most accomplished examples of Romanesque in Apulia), with the façade of the abbey church (the most important and best-known building in the complex) built with ashlars of white Lecce stone. The very facade of the church is perhaps the best known and most recognizable element of the abbey. It is a salient, tripartite façade with a rose window, typical of Romanesque buildings, opening at the top, and with thin pilasters emphasizing the tripartition, while ten small hanging arches (four in the center and three on the sides) run horizontally above two single-lancet windows on either side of the entrance portal. The latter, surrounded by decorations with elegant plant motifs, is surmounted by a richly decorated arch: the intrados, in particular, is ornamented with figures recalling episodes from the infancy of Jesus Christ (although different readings have been proposed for the characters, since they are not easy to interpret). The six ashlars of the arch were in fact carved, and the reading that interprets them as moments related to the birth of Christ is the one that has received the most favor: according to Cosimo De Giorgi, who devoted a study to the abbey in the late 19th century, the ashlars would represent, in order (starting from the right), Saint Michael, the baptism of Christ, the nativity, theadoration of the Magi, the visitation, and a Basilian monk (the fact that the order does not follow the exact chronology of the episodes in the life of Jesus might suggest that in the past the arch was disassembled and then reassembled in an incorrect order). A 13th-century small cloister was also attached to the left side of the church.

Inside, the church has a longitudinal basilica plan, that is, without a transept, and is divided into three naves by mighty columns above which rise pointed arches. At the back, the high altar is surmounted by a 13th-century ciborium (the only one of the medieval furnishings that is still preserved), but what most attracts visitors and makes the complex important are the extraordinary frescoes that are preserved at Santa Maria di Cerrate, and they are among the greatest examples of Byzantine painting that we can observe in southern Italy (and beyond).

|

| Interior of the church of Santa Maria di Cerrate. Ph. Credit FAI |

|

| Interior of the church of Santa Maria di Cerrate. Ph. Credit FAI |

On why these frescoes are so important, Marina Falla Castelfranchi wrote in 1991: "the frescoes of Cerrate, which deserve a much deeper exegesis, occupy [...] a prominent place not only within the Byzantine pictorial production of Salento, but also within the broader framework of Byzantine painting proper. The remote elegant beauty of the frescoes of the apse, of its decorative parties, which, particularly in their relationship with the images of deacons and with the vegetal capitals on columns, constitute a remarkable episode for the quality of the pictorial material and the skill in inventing and reinventing arrangements and transitions from one apse to another, all this and more is not easy to express. Where then the workers came from, if, as they say, not only local, seems at this point a non-problem. The existence of such frescoes in Salento in itself seals and guarantees the quality of the artistic culture of this area in the Middle Ages. As for then the vexata quaestio about their dating, it should be pointed out that to the original program belong the frescoes of the apse and subarches and perhaps some fragments on the right side, while the other frescoes would seem to be able to be assigned to later phases, of which the last testimonies are represented by the beautiful koimesis now in the Abbey Museum (first half of the 14th century or so), and then by the late Gothic frescoes, also preserved in the same Museum."

For a long time, the importance of the frescoes of Santa Maria di Cerrate has been underestimated, and the reason is quickly said: apart from the late 19th-century studies conducted by important scholars such as Cosimo De Giorgi and Sigismondo Castromediano, no monographic reconnaissance of these paintings has ever been produced. In recent times, dealing with the Abbey’s frescoes has been the Abruzzi-based art historian Valentino Pace, until 2014 full professor of medieval and Byzantine art history at the University of Udine: one of the most extensive recent articles on the frescoes dates from 2008 and bears his signature.

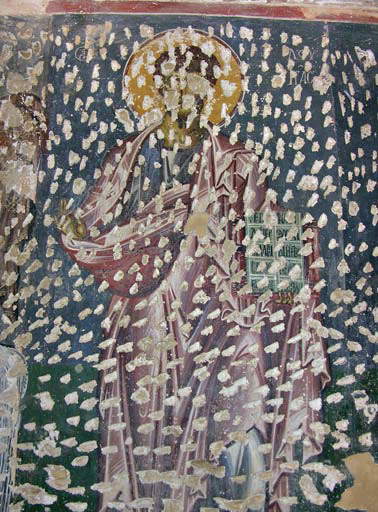

In this essay, Pace wrote that the worshipper, upon entering the space of the abbey church, found himself in a place “of which the most emergent visual sign was and still is given by the presence of the images of monastic sanctity, displayed on the intradoses of the arcades of the passages.” And indeed, the arches abound with images of Basilian saints and monks, running along all the intrados and accompanying the visitor toward thecentral apse (the abbey church in fact features a triple apse, typical of the worship buildings of Eastern Christianity), where Christ’s ascension takes place, transported to heaven in a mandorla supported by a pair of angels, one on each side. Below this depiction, we see the apostles witnessing the scene, all arranged horizontally and on a single plane, in typical Byzantine art fashion. The apostles are divided into two almost symmetrical groups, and with the praying Madonna in the center, depicted half-length as she is placed exactly above the single lancet window that gives light to the apse. Below still, we find five figures also arranged horizontally: they are five bishops, one of whom is Saint Basil. Other bishops are also found in the prothesis (the side apse used as a place where the liturgy is prepared and sacred objects are kept), in sequence with those in the central apse, reasoning, Pace speculates, that the same pattern must have been repeated in the diakonikon (the other side apse, intended as a place where sacred vestments were kept), where the paintings are now practically lost.

|

| The “puzzle” fresco |

|

| Ascension, details with figures of the apostles (church of Santa Maria di Cerrate) |

|

| Holy bishops (church of Santa Maria di Cerrate) |

|

| Saint Luke (church of Santa Maria di Cerrate) |

|

| The Annunciation preserved in the museum |

The frescoes decorating the arches and apse have also been identified as the oldest in the complex. Later paintings decorate the walls instead: figures of saints (including a St. Luke and a St. George that have undergone extensive staking, a sign that in more recent times they were covered with plaster so that the walls could be decorated again) and monks, and also a Virgin Child in the arms of her mother, St. Anne, together with her father, namely St. Joachim. Somewhat bizarre, on the other hand, is the situation of the right wall: evidently in ancient times the wall was destroyed, and those who built it did not pose the problem of repositioning the fragments in a logical order but only concerned themselves with reassembling the wall, with the result that today the decorations appear to us as a kind of large puzzle to be solved. Some faces of saints and portions of drapery are recognizable, but not much more can be guessed. Other saints, in a very precarious condition of legibility, finally decorate the counterfacade.

These frescoes, wrote Valentino Pace, “are sure expressions of Greek monastic religiosity and for this reason their importance goes beyond what even visually emerges from their placement in the ’figurative’ ecumene of Byzantium.” We do not know with certainty, however, the time of their creation: on the basis of some comparisons (for example, with the paintings in the church of St. George in Kurbinovo, North Macedonia, or those in the church of Episkopi in the Peloponnese) it is possible to imagine that the paintings were executed between the end of the 12th century and the first decades of the 13th. In any case, Pace concludes, “whatever the date of the Cerrate pictorial campaign, whether its execution is unified or differentiated, undoubtedly, however, it bears full witness to its inherentness in the Greek figurative, which the Salento testifies not only with monuments such as this one, but also, with no less force, with the vicissitudes of its monasteries, with the history of their religiosity, with the production and importation of its books, with its epigraphic evidence.”

Later, however, are the frescoes preserved in the museum set up in what was once the Massaro’s house: they date back to the 14th century and we recognize there anAnnunciation, a St. George freeing the princess, a Koimesis i.e., a Dormition of the Virgin, and others, all painted by an artist of Western culture. And which were restored at the time of the tear.

Of course, the restorations are not yet finished: at the moment, work is underway to restore the cistern and the rainwater supply system, and restoration on the Abbey’s dry stone walls and boundary walls, while fundraising is underway for the restoration of the hypogeous oil mill in the southern body of the complex and the restoration of the former stables to convert them into a multipurpose space. Restorations that will complete the ambitious project of making the Abbey of Santa Maria di Cerrate a place increasingly capable of revealing all its history through art. Certainly, it is impossible to know what the forms of the buildings that composed it originally were and what works of art are preserved inside: however, the Cerrate complex does not cease to remain a unique place for culture in Apulia and a site where it is possible to clearly understand how the stratification of a building with a centuries-old history develops.

Reference bibliography

The author of this article: Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta

Gli articoli firmati Finestre sull'Arte sono scritti a quattro mani da Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta. Insieme abbiamo fondato Finestre sull'Arte nel 2009. Clicca qui per scoprire chi siamoWarning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.