Vittorio Sereni was convinced that passion for sports was a kind of grand allegory of life. And that the “soccer league cheer,” as he, an avid Inter fan, called it, found its root in the overlap between the temperament of the fan and the “figure” that the team takes on before his eyes. By analogy, “but also by contrast,” Sereni said, “or simply by complementarity with respect to the image you have of yourself.” They all lie here, the reasons why we light up in front of a sporting event. The player, the team become “a metaphor for your existence.” The fate of one’s favorite almost a “diagram of your destiny.” That is why sports is such a cross-cutting phenomenon. That is why it can be said, without fear of venturing into wild conjecture, that sports, whether we like it or not, punctuates our existences. It does for so many, perhaps for almost everyone. Each of us cherishes, more or less, a memory related to sports. I am convinced that those of my generation remember well where they were, and who they were with, when Fabio Grosso slotted the ball to the left of Fabien Barthez and gave Italy the 2006 World Cup. Or they retain some faint trace of summer Sundays spent watching duels between Schumacher and Häkkinen on Formula One circuits on television. Of the still cold winters when Hermann Maier would descend on the ski slopes and devour the tracks, leaving his opponents to fight for the place of honor at most.

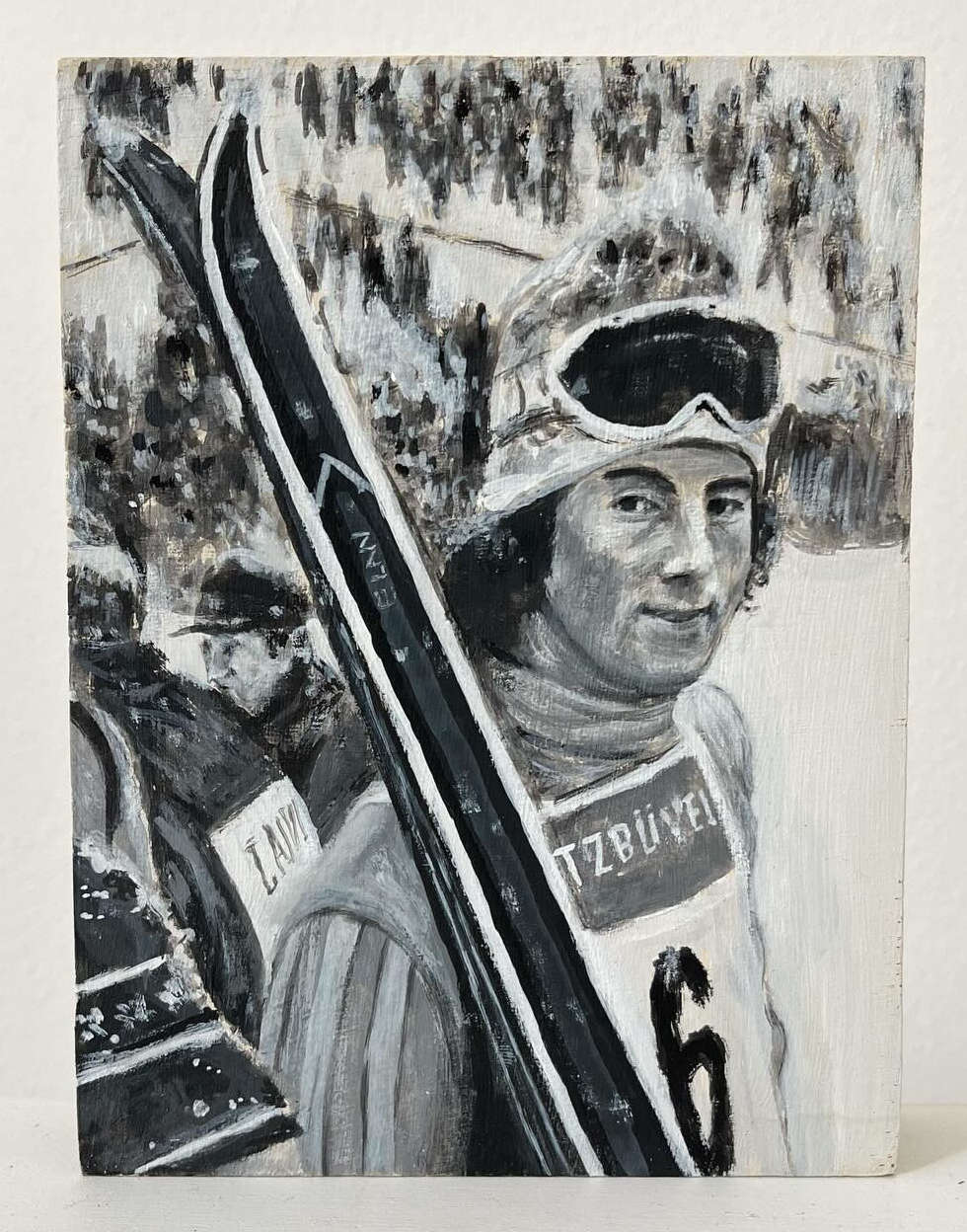

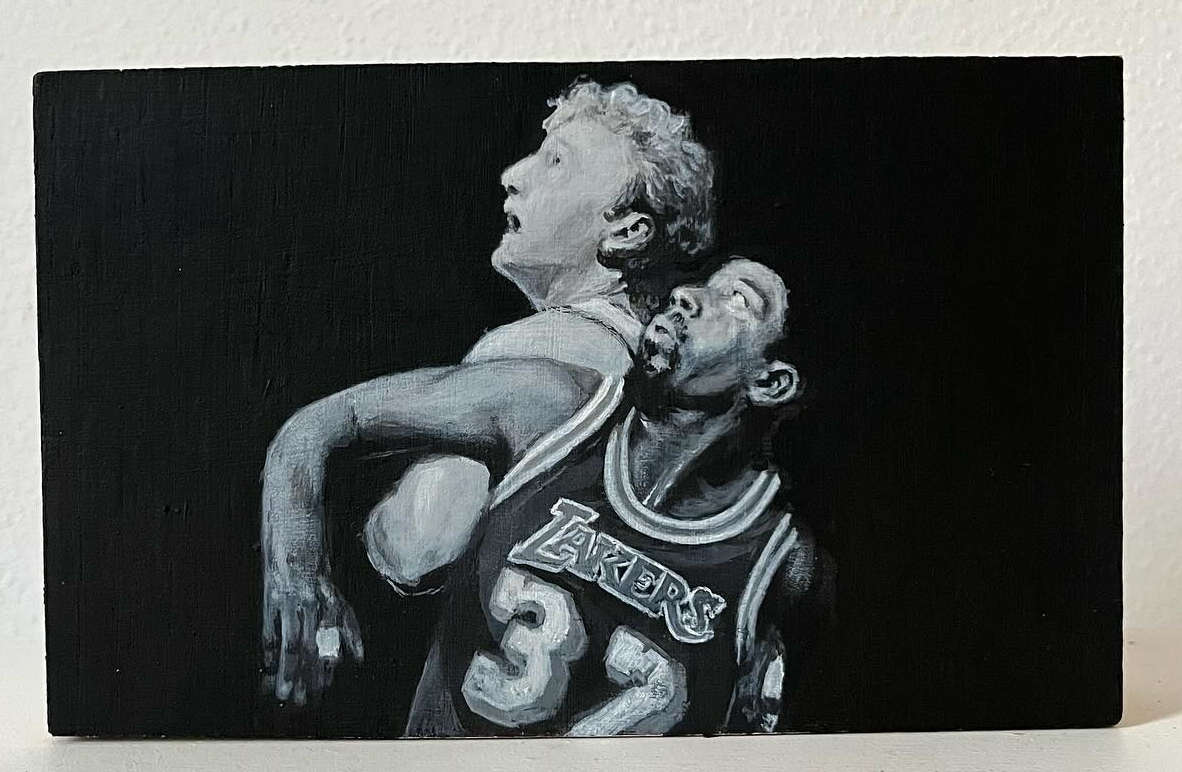

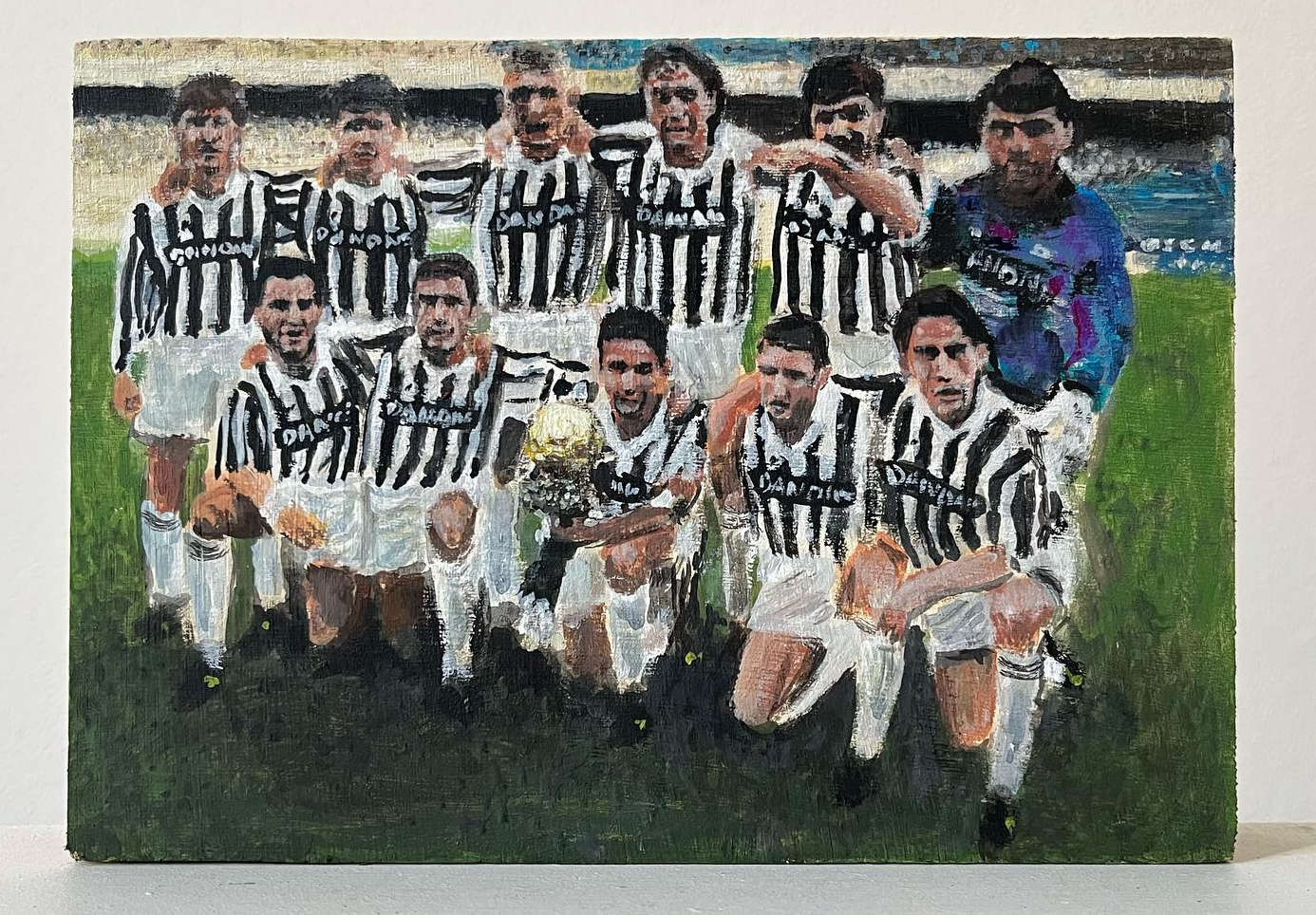

Everyone has his own sporting imagination. It has its own memories linked to the feat of some champion. It has its own pantheon of great or lesser-known names. The imagination of Simone Tribuiani, a painter from Cesenatico who, for some time now, has been giving shape with his colors to the memories of recent or distant sports feats, is populated by the heroes of soccer, tennis, and basketball. In Bologna, at the 50th anniversary edition of Arte Fiera, at the booth of Studio d’Arte Raffaelli, the gallery that together with Cellar Contemporary represents him, he shows me some of his latest paintings. There is Inter winning the 1994 UEFA Cup. There is Juve with Roberto Baggio, fresh winner of the Ballon d’Or, smilingly displaying the trophy he just won before a game with Foggia. There is a series of portraits of skiers in black and white, I recognize Ingemar Stenmark, the greatest in history. There are some basketball players, whom I cannot distinguish instead, being sports with which I have never been very familiar: I just read on one jersey the name of the Los Angeles Lakers. And then there is Jannik Sinner. The new apostle of Italian sports.

Simone Tribuiani

Simone Tribuiani Simone Tribuiani

Simone Tribuiani Simone Tribuiani

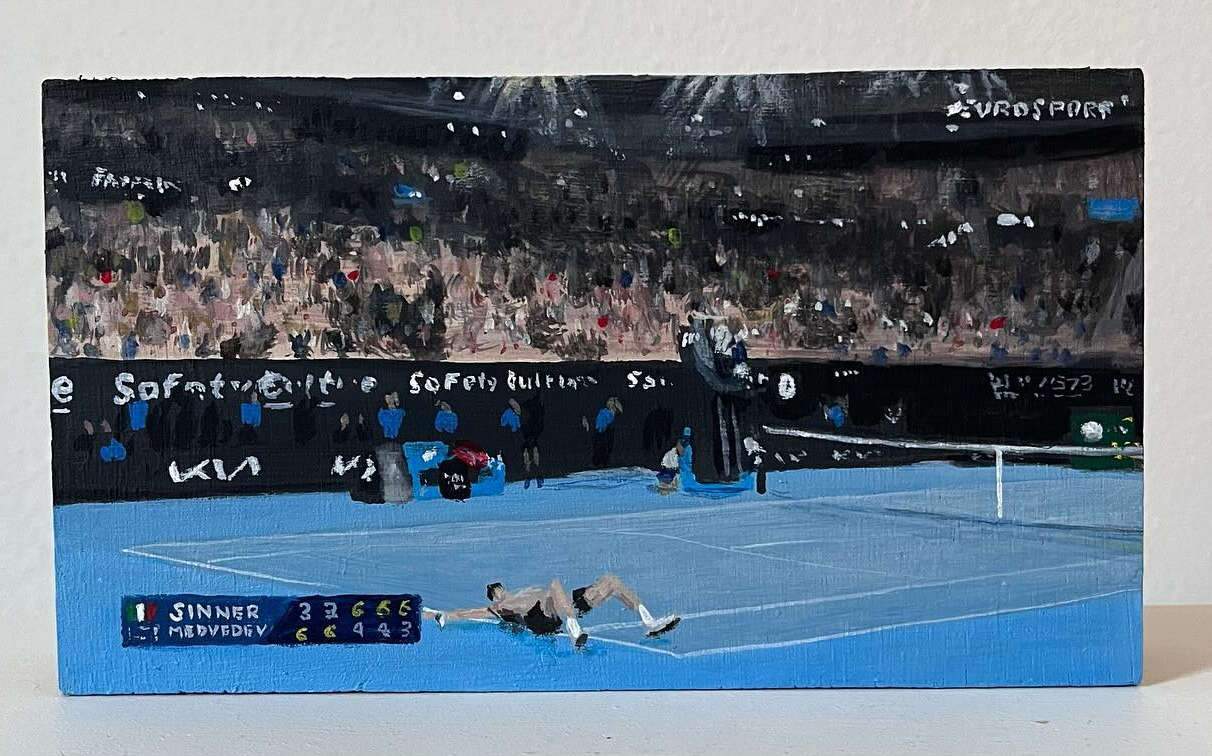

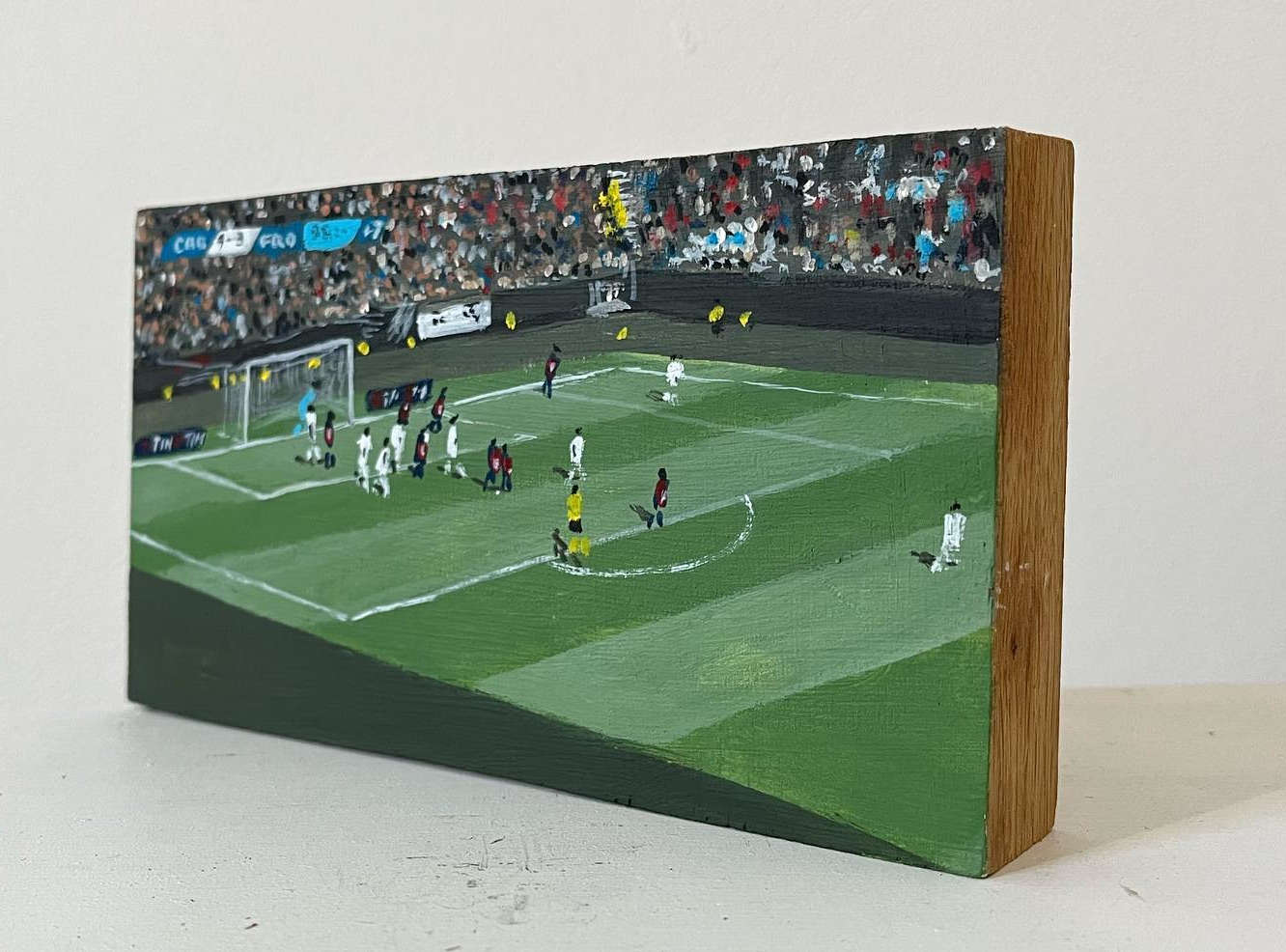

Simone TribuianiTribuiani captured on his tablets some moments from his most recent matches. A match in Vienna against compatriot Lorenzo Sonego. The clash with Novak Djokovic in Malaga in the Davis Cup semifinals, the last hurdle before the victorious final over Australia, with Italy bringing back under the Alps that trophy that had been missing for more than 40 years, from the days of Panatta, Bertolucci and Barazzutti. And the final match with Daniil Medvedev in Melbourne, the first Australian Open won by an Italian. Tribuiani felt that match was destined to go down in history. And he fixed the highlights on the board. One of the paintings in the series rewinds the moments leading up to the Championship point, as the title informs us: Sinner’s violent longline forehand, hurled at more than 160 kilometers per hour, which Medvedev stands by, unable to oppose in any way. Nearby, in Sinner’s ATP Melbourne Winner, Tribuiani suggests the image that perhaps more than any other has stuck in the memory of Italians, a bit like Tardelli’s run or Grosso’s, like the embrace between Tamberi and Barshim at the Tokyo Olympics, like Pantani stopping to put on his cape on the Galibier: that of Jannik Sinner lying on the ground, excited, panting, arms spread wide, overwrought with fatigue, and with the Eurosport overlay staring at the final score, 3-6 3-6 6-4 6-3. "They are like stills, like screenshots," Tribuiani tells me, pronouncing each syllable with his marked Romagnolo accent. His painting, cursive, delicate, evocative, with a fine, uncertain brushstroke, is reminiscent of Francis Alÿs’s miniatures: like the Belgian, Tribuiani also operates a sort of transfiguration of what he sees, converting a frame of a sporting event into a hazy dream, into a flickering image, into the ghost of a match. Faint colors, indistinct crowds, faces without connotations. “I paint sports,” Tribuiani continues, “because I carry my childhood passions with me. And I associate it with my daily life, also because these works are made on pieces of wood that come from salvaged shipyard scraps. They were my childhood toys. And I continue to repurpose them in an artistic way. I combined my passions, in short.” Prices, moreover, are very low to take home one’s favorite sports souvenir, given that the passions Tribuiani cultivated when he was a child can easily coincide with those of a large part of the public: they range from something less than 500 euros for the smallest sized squares to just over 1,000 for the largest format works, including VAT.

On the one hand, there are the people who have marked the history of sports. On one wall, for example, there is also the 2023 Scudetto winner Napoli. There are all of Jannik Sinner’s recent matches, the most epic ones, because one cannot disagree that the South Tyrolean redhead, despite his twenty-two years of age, has already written seminal pages of his sport. And on the other hand, there are the sportsmen and women who have left something behind in Tribuiani: “I think I did all sports, even though... I was a dud everywhere. I played Tennis, I played football, I did some basketball, even played baseball. Now I’ve got back my passion for cycling, which I had as a boy: by the way, I recently learned that when I was cycling in the juniors in my neck of the woods Marco Pantani was racing, although among the slightly older boys.” In his paintings there are the champions from when he was a child or boy, for example Paolo Maldini together with his father Cesare, Uncle Bergomi at the World Cup in Spain in ’82, a portrait of Zico that “is like a contemporary holy card,” the artist notes. After all, Pierre de Coubertin already said that sport is “a religion with its own Church, its own dogmas and worship, but above all with its own religious feeling.” Going into more detail would be Pasolini: “soccer is the last sacred representation of our time. It is ritual in the background, even if it is evasion. While other sacred representations, even the mass, are in decline, soccer is the only one left to us. Soccer is the spectacle that has replaced theater. Cinema could not replace it, soccer could, because theater is a relationship between a flesh-and-blood audience and flesh-and-blood characters acting on the stage. Whereas cinema is a relationship between a flesh-and-blood audience and a screen, shadows. Whereas soccer is again a spectacle in which a real, flesh-and-blood world, that of the stadium stands, is measured against real protagonists, the athletes on the field, who move and behave according to a precise ritual. So I consider soccer the only great ritual left to our time.”

Sometimes this religious sense invests both the sacred and the profane at the same time: for example, Tribuiani points out to me, last year Napoli won the Scudetto around Easter, and it had not been able to do so for some 30 years. “The image I go for,” the artist says, “has to deliver something to me. Some players are almost invested with a religious aura. Others, however, have faces that speak of the land from which they come.” He points me to a portrait of René Higuita, a funambulistic Colombian goalkeeper of the 1990s, another legend of my generation. A search for “the moment and the character that moves my interest and, I would say, the common one, because they are all characters who have left a mark anyway.”

Simone Tribuiani

Simone Tribuiani Simone Tribuiani

Simone Tribuiani Simone Tribuiani

Simone Tribuiani

And just as in ancient times private devotion was professed in front of small panels or small polyptychs that painters painted for moments of domestic recollection, so today Tribuiani offers the sports faithful their sacred images. It will be said, however, that today there are photographs and posters to provide fans with visual support for their passion: what good will a painter ever do reproducing the 1994 Inter team lineup on a panel, or the moment Jannik Sinner triumphs at the Australian Open? What use will a painter ever be when it is enough to open any website, any Instagram profile, to see, reproduced hundreds of thousands of times, the same image of the tennis player from San Candido lying on the synthetic of Rod Laver Arena? One might be content with a comfortable answer, remembering that a photograph or poster takes one back to a childhood dimension, to the bedrooms where we hung pictures of our favorite champions, and a painting gives a more pronounced sense of authority. Or, in a more biting way, one could say that painting is the stuff of nostalgics, for people who have not yet realized that we have long since crossed the frontiers of the third millennium, and that therefore a painted piece of wood is at best a beautiful vintage object endowed with a different charm than a photograph. In reality, the matter is more serious.

One could reply, for example, with the same answer that Francis Alÿs would give, since we mentioned him: a painted image manages to convey the complexity of the world much better than a post on Instagram does. It also applies to sports: photography is the capturing of a moment, it is the arresting of a precise instant of a game caught in the midst of its unfolding. Photography is presence. Painting is, if you will, its opposite: it is the reworking, more or less conscious, of that event. Painting is absence. Or rather: it is absence that nevertheless suggests the view of a place, of a moment. It serves to build or reconstruct worlds; it is an electrical impulse that awakens our imagination. This was well known by painters who painted devout images in the 16th century, keeping in mind the teaching of Ignatius of Loyola’s Spiritual Exercises : “the composition will consist in seeing with the sight of the imagination the material place where the thing I want to contemplate is.” The painted image arouses a vision. And the image painted by Tribuiani, veiled by the haze of temporal distance, arouses the vision of a sporting feat, which may have been part of our lives: the players on the field are unrecognizable, the lines on the court are blurred, the lettering on television broadcasts can barely be distinguished, the score numbers are difficult to read, because the greater the distance from the event, the harder it is to recall it. Tribuiani’s images are painted reminiscences, appearing to us in the same form that memories appear in our minds. Images vague, misty, confused like fumes, and yet so present, so alive, so capable of kindling dormant feelings, covered by the mists of years. The less exaggerated Interista will not remember by heart the lineup of the UEFA Cup winning team, he will barely recall the names of Zenga, Bergkamp and a few others. The Juventus fan will not remember all the names of Roberto Baggio’s teammates. The avid skier will not remember who came in behind Ingemar Stenmark at the Lake Placid Olympics. Today almost everyone can repeat by heart the score of the Sinner-Medvedev game. But in a few years almost all of us will forget it, perhaps even forget the name of Sinner’s opponent. But we will remember how all of Italy, for a few days, was in awe of that skinny, red-haired boy who wrote a new chapter in tennis history. And we will remember where we were at that moment, who we shared it with, what we were doing. Remembering is not necessarily synonymous with nostalgia, however. Remembrance is a moment of suspension of reality into which infinity enters. Or within which, at most, an emotion is produced. And it is on this ground that Tribuiani’s sports pictures disclose their glimmer.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.