In Gianfranco Ferroni’s art, there is a before and there is an after. And the watershed is the 1968 Venice Biennale. It is June 18, the day when the preview of the great international exhibition opens: in St. Mark’s Square, which is not yet a pasture for tourists in flip-flops but is a habitual meeting place and social gathering place for Venetians, a few dozen students gather to demonstrate against the art of the masters, against what is seen as the highest expression of capitalist exploitation of art and the commodification of art, against the Biennale’s statute that still dates back to the fascist Twenty Years, against the police. The goal is to extend the boycott action against the Biennale. At one point a brawl breaks out involving a photographer (the press, anticipating incidents, had immediately flocked to the square) and a couple of boys who pull out a flag: enough for the celere to charge and truncheon the students. L’Unità, a few days later, will report that some of those stopped were taken to the Procuratie Nuove and clubbed between two wings of police. And on the 23rd, neo-fascists will throw petrol bombs at the Academy of Fine Arts occupied by students. The climate, then, is heavy: and the Biennale opens well guarded by law enforcement.

For many artists, however, they lack the cultural freedom necessary to take part in the Biennale: of the twenty-two Italians invited to the international exhibition, nineteen enact a protest and prevent critics and journalists who have come for the preview from seeing their works. Some remove them, others hide them, some turn them against the wall. However, the protest is very short-lived: already the next day almost all the artists fall back into ranks. Only three continue: Gastone Novelli, Carlo Mattioli and Gianfranco Ferroni. Novelli and Mattioli withdraw the works, “in view of the anti-cultural climate created, in view of the absurd displays of force by the Venice police and those called from Padua and Trieste, in view of your complete lack of political sensitivity to the problems of the moment,” Novelli will write to the Biennale leadership and the press. Ferroni, however, has them remain turned to the wall for the duration of the exhibition.

The Biennial of ’68 represents, by Ferroni’s own admission, the end of illusions, the emblem of unfulfilled hopes, the frustration of his art of denunciation: the consequence is a period of crisis, isolation, disgust with the system, a period of low activity, and an escape to Versilia. Ferroni will find peace only in a totally renewed art, and turned toward himself: an intimist, reposed, rarefied art, an art of inner exploration, secret, ascetic and atheistic at the same time. An art that will be able to produce surprising results, an art that, Vittorio Sgarbi wrote, “does not have to denounce anything, it only wants to confide its secret heart, to delimit the boundaries of its consciousness.” Before ’68, however, there is another Ferroni: there is an early expressionist Ferroni who scandalizes the critics, there is the Ferroni who turns on the subversive impulses of the Neue Sachlichkeit, there is a deeply political Ferroni, a Ferroni who also looks to Pop Art, but to overthrow its enthusiasms. Take, then, a work such as Rifiuti.

|

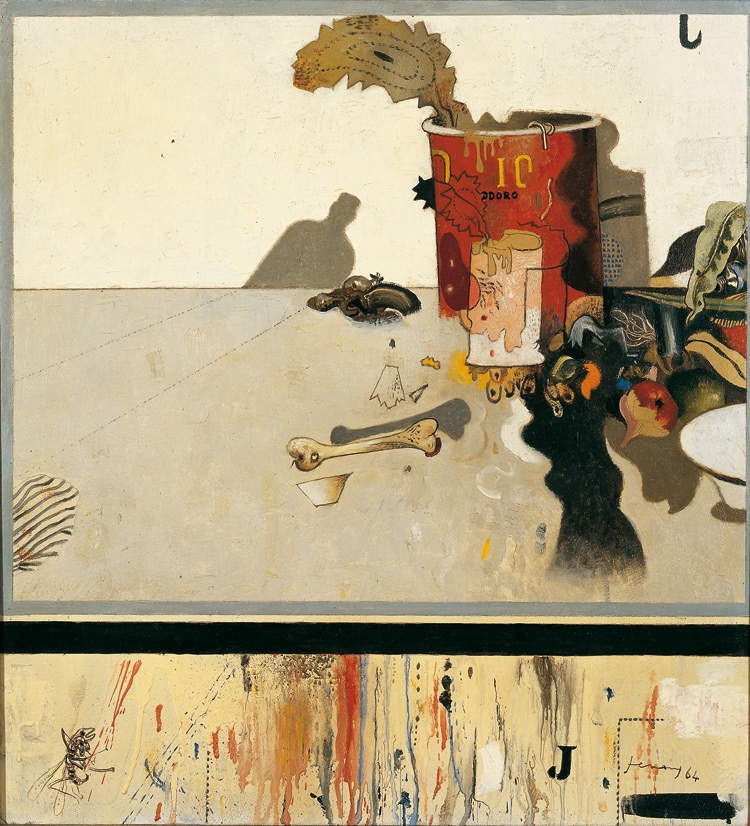

| Gianfranco Ferroni, Rifiuti (1964; oil on canvas, 52 x 47 cm; Private collection) |

This is an oil on canvas from 1964: on the surface, it presents the viewer with nothing more than what the title communicates. Garbage: stripped bones, wastepaper, an uncovered tomato can, empty plates, leftover fruit, wires and wrappings, all on a foreshortened plane in side perspective, perhaps a table, perhaps the floor. Underneath, in the lower register, dripping colors and the image of a bizarre, ancipitous wasp that seems to be gasping, taking its last breaths. A dirty subject, but a neat, clean painting, like the sound of jazz of which Ferroni was a great fan (he played saxophone). A controlled, slow, artist-craftsman kind of painting: the exact opposite of Pop Art practice, and a method more congenial to him, a learned and settled artist, an artist who detested traveling, an artist according to whom poetry cannot be born in a vacuum, but must necessarily germinate where there is a tradition.

His main aesthetic concern, at this stage of his career, is to find a balance that results from the balancing of a rigorous spatial analysis with messy piles of objects crushed on the canvas by the two-dimensional language of Pop Art, and yet which acquire a vigorous solidity through strong contrasts of light and shadow, always present in Ferroni’s art in these years. Objects that, critic Giacomo Giossi has written, also become “psychoanalytic,” elements of a confusion that “becomes the clarifying order of a reality that is impossible to reduce or frame in its continuous dialogue with the ego.” A thoughtful, and already intimate and internalized version of the suggestions that were coming from overseas, one might say. Rejections that in turn refer back to a messy reality: “I don’t abstract myself from society,” the artist said. “I wanted to fill my vision of nature,” he would later say of some views of Lake Massaciuccoli painted right around the time of Refuse, “with subtexts, with presences, like the dead, crushed insect that appears in many of my paintings and etchings on this subject, and if you look closely, this insect, it has two heads and a scream, a scream that you can’t hear, but that is there.” These are paintings where “death manifests itself in the apparent calm, and even there everything is overpowering again.”

The origin of Refuse is to be sought further back in time, perhaps as early as the time of the 1956 study trip to Sicily, from which Ferroni returned with clear ideas, with a desire to move away as much from abstractionism and informalism, which never interested him, as from social realism, to find another way: “putting the ’thing’ in front and painting it without ulterior motives or myths,” as Giorgio Mascherpa summarized. A new poetics of the object that would lead Ferroni’s omnivorous painting to the outcomes of the 1960s, strongly rooted in his intellectual attitude of those years. And this disenchanted reading of Andy Warhol’s cans, which preceded Refuse by just a couple of years and which from totems of the glittering consumer society turned, in Ferroni’s painting, into unserviceable, throw-away piles of tin, is rooted in his attitude toward society. “Ferroni’s nature, his instincts, his tendencies,” wrote Roberto Tassi in 1997, “have always been directed toward a participation in the life and reality of others, of man and his affairs. There is in him this openness, which we can place in the sign of generosity and victory over selfishness; and which leads him, as he acknowledges, to be always in relation, very connected, to everything that happens around him on the political and human level.”

Tassi recalled that, since the 1940s, Ferroni’s mind was occupied with the idea of man’s liberation from exploitation, perhaps the only one that never left his worldview. And perhaps we almost seem to catch a glimpse of it even behind that pile of garbage.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.